🧵regarding the 'rapidly absorbable' sutures, which are used less often than other suture types, but fill specific roles in a number of different surgical specialties.

We'll go over the uses of (and differences between) Chromic, plain gut, 'fast' gut, and Vicryl Rapide.

(1/)

We'll go over the uses of (and differences between) Chromic, plain gut, 'fast' gut, and Vicryl Rapide.

(1/)

Catgut has been used for suturing for many centuries, but it first became industrialized by the German company B Braun.

It is not (and probably never was) made from cats; instead it comes from the serosal layer of beef intestine or the submucosal layer of sheep intestine.

It is not (and probably never was) made from cats; instead it comes from the serosal layer of beef intestine or the submucosal layer of sheep intestine.

Catgut sutures are strands of ~90% collagen that are purified and chemically processed.

Because collagen is a protein, the longevity of the sutures is very much affected by any proteolytic enzymes in the local environment. We'll see why this is important later.

Because collagen is a protein, the longevity of the sutures is very much affected by any proteolytic enzymes in the local environment. We'll see why this is important later.

Surgeons recognized that plain catgut sutures simply did not last long enough for most purposes.

'Chromic' gut sutures were invented by Lister in 1881 in an attempt to solve this problem. By treating the catgut with chromic salts, it lasted longer.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/P…

'Chromic' gut sutures were invented by Lister in 1881 in an attempt to solve this problem. By treating the catgut with chromic salts, it lasted longer.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/P…

Since Chromic is the variety of gut suture that is most often used, we'll start with it.

The collagen strands are treated with chromic acid salts, giving them a brownish color, and the strands last much longer. The process also makes them stronger than 'plain gut' sutures.

The collagen strands are treated with chromic acid salts, giving them a brownish color, and the strands last much longer. The process also makes them stronger than 'plain gut' sutures.

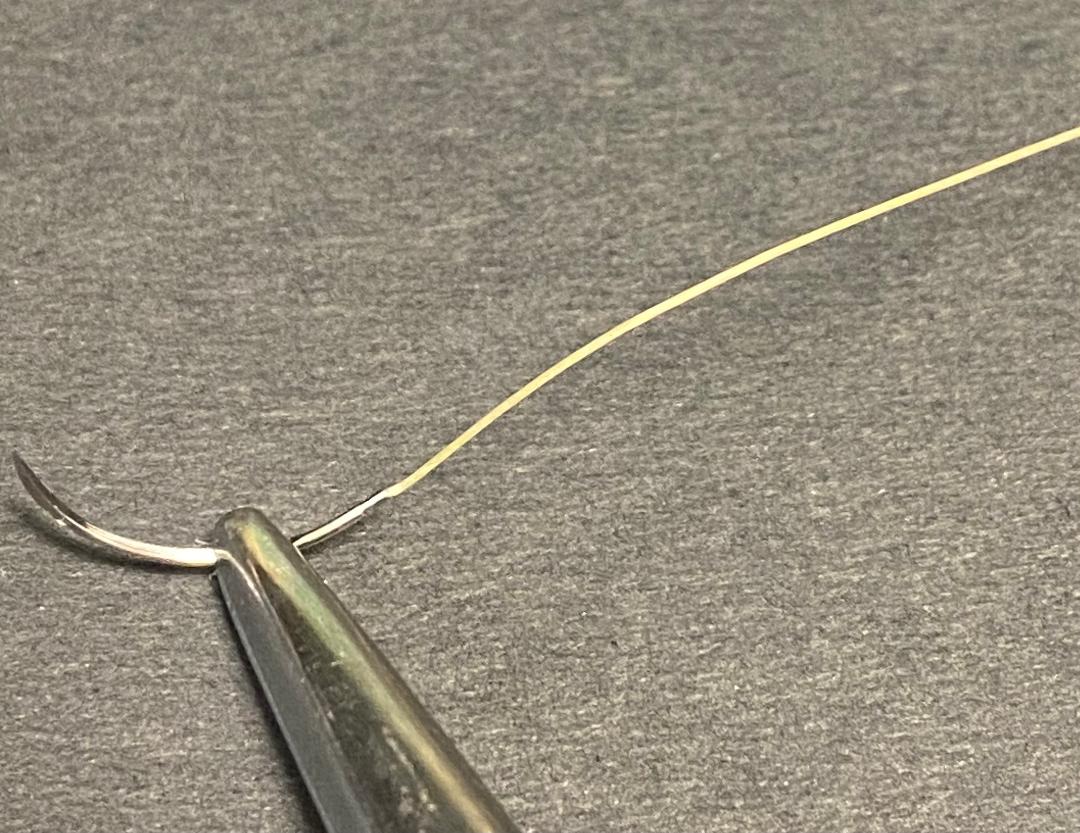

Chromic suture feels quite stiff when you're tying with it, but it 'sets down' extremely well.

When you 'set' down a throw, it tends to stay there...more so than for any other suture material.

Due to the high friction, there is minimal need for slip knots or surgeon's knots.

When you 'set' down a throw, it tends to stay there...more so than for any other suture material.

Due to the high friction, there is minimal need for slip knots or surgeon's knots.

Chromic suture 'sets' down well and has excellent knot security, but because it's stiff, you will have to have good square knot technique, because the Chromic suture is less forgiving than others if the knots aren't tied right.

I usually tie 5 knots with chromic sutures.

I usually tie 5 knots with chromic sutures.

In the early 20th century, when Chromic was practically the only absorbable suture available, it was used for almost everything that you would now use synthetic sutures like Vicryl or PDS for.

It was used for all types of GI, GU, GYN, orthopedic, and many other operations.

It was used for all types of GI, GU, GYN, orthopedic, and many other operations.

Chromic sutures are strong, but only for only 10-14 days, so when would they be used today?

They're used for rapidly healing tissues in places where you want them to disappear quickly.

Its most common use is probably in ENT operations, but it is also used in urology, dentistry, and occasionally in OB/GYN (for episiotomies and the "B-Lynch" suture.

They're used for rapidly healing tissues in places where you want them to disappear quickly.

Its most common use is probably in ENT operations, but it is also used in urology, dentistry, and occasionally in OB/GYN (for episiotomies and the "B-Lynch" suture.

In trauma surgery, 0 or #1 Chromic sutures are used to suture some of simpler, more linear liver lacerations.

In this case we're not really using it because of the properties of Chromic suture itself, but more likely because it comes on this huge, blunt point ("BP" needle).

In this case we're not really using it because of the properties of Chromic suture itself, but more likely because it comes on this huge, blunt point ("BP" needle).

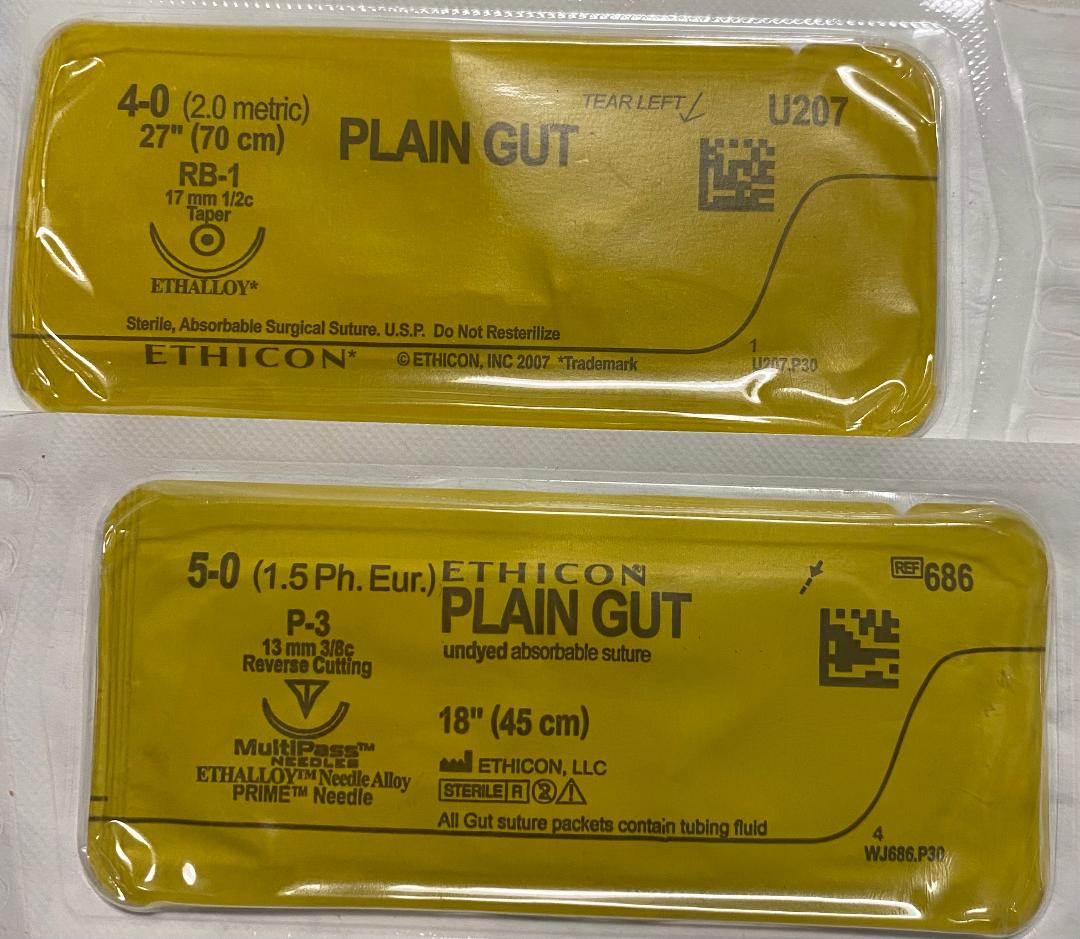

Now for 'plain gut' sutures.

Plain gut sutures are not treated with chromic acid salts. They don't last as long (7-10 days or even less) and they also are not as strong as Chromic.

So they're used when you *want* them to dissolve quickly (and you don't have to cut them out).

Plain gut sutures are not treated with chromic acid salts. They don't last as long (7-10 days or even less) and they also are not as strong as Chromic.

So they're used when you *want* them to dissolve quickly (and you don't have to cut them out).

The use of 'plain gut' sutures seems to be almost all in head and neck procedures. Our 'ENT' cart stocks them.

They are used for facial lacerations and for many types of ENT, oral, dental, and eyelid surgery, where removal of the sutures would be difficult or impractical.

They are used for facial lacerations and for many types of ENT, oral, dental, and eyelid surgery, where removal of the sutures would be difficult or impractical.

There is also a 'fast absorbing' plain gut suture that is heat-treated so that it lasts even *less* time than plain gut. It is also a little weaker.

Fast absorbing plain gut only comes in one size (5-0 for Ethicon) and is used only for skin closures (usually on the face).

Fast absorbing plain gut only comes in one size (5-0 for Ethicon) and is used only for skin closures (usually on the face).

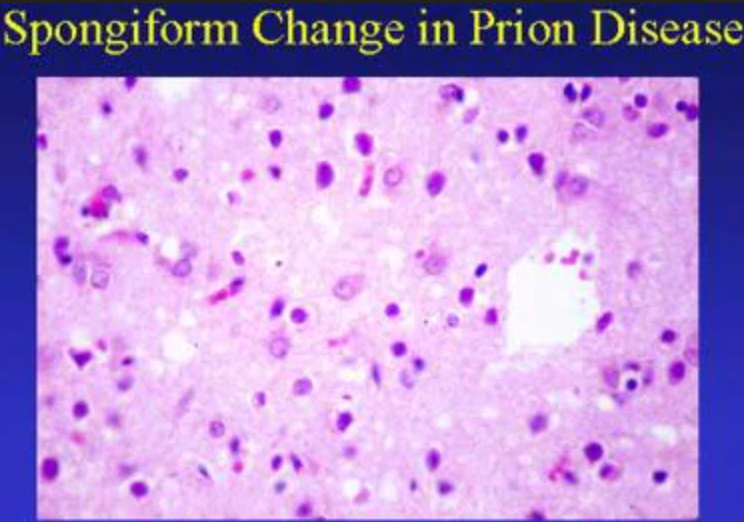

Catgut-based sutures (like 'chromic' gut and plain gut) have been banned for many years in the EU, Japan, and possibly elsewhere due to the theoretic risk of transmitting Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy, though no cases of this have happened.

They remain in use in the U.S.

They remain in use in the U.S.

Before we leave catgut-based sutures, I had mentioned that proteolytic enzymes break down the collagen strands that make up the suture.

In areas where there is ⬆️proteolytic enzyme activity, like the mouth, the sutures will dissolve faster than they would if placed on the skin.

In areas where there is ⬆️proteolytic enzyme activity, like the mouth, the sutures will dissolve faster than they would if placed on the skin.

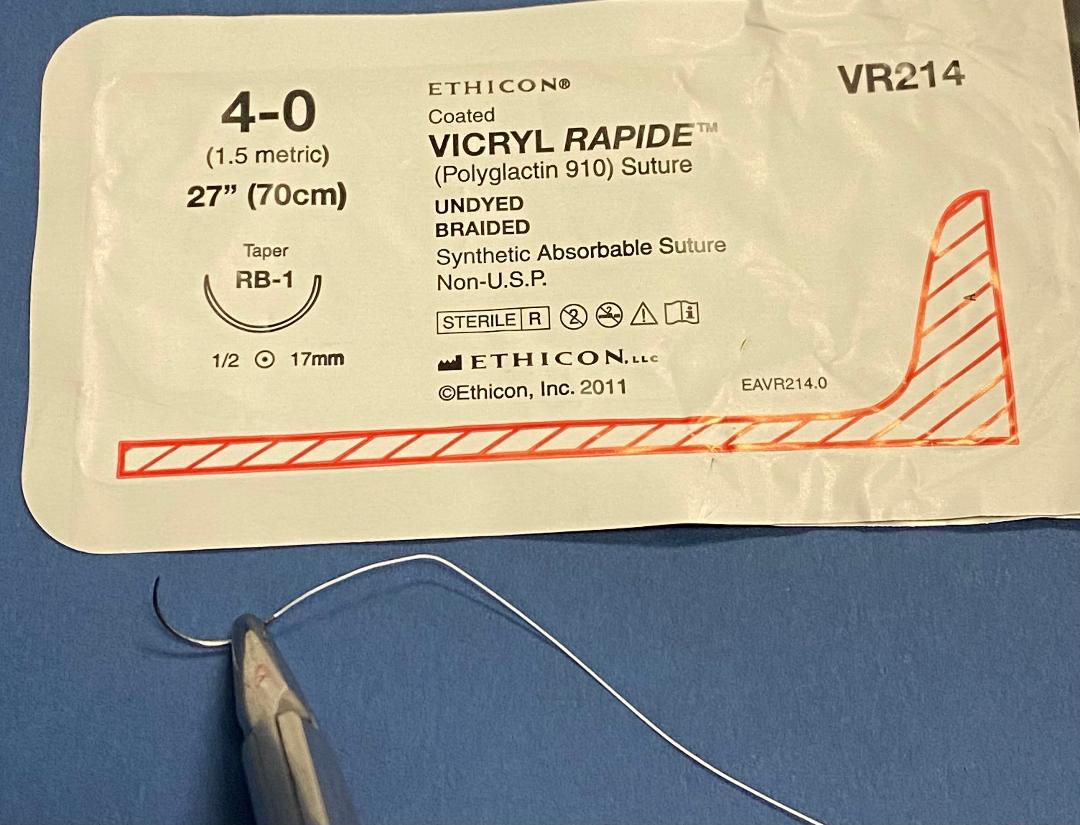

Finally, there is Vicryl Rapide.

Vicryl Rapide is often used when a rapidly absorbing suture is desired, and gut-based sutures are not available or the surgeon does not want to use them.

It is made by irradiating the same polyglactin 910 polymer used for 'normal' Vicryl.

Vicryl Rapide is often used when a rapidly absorbing suture is desired, and gut-based sutures are not available or the surgeon does not want to use them.

It is made by irradiating the same polyglactin 910 polymer used for 'normal' Vicryl.

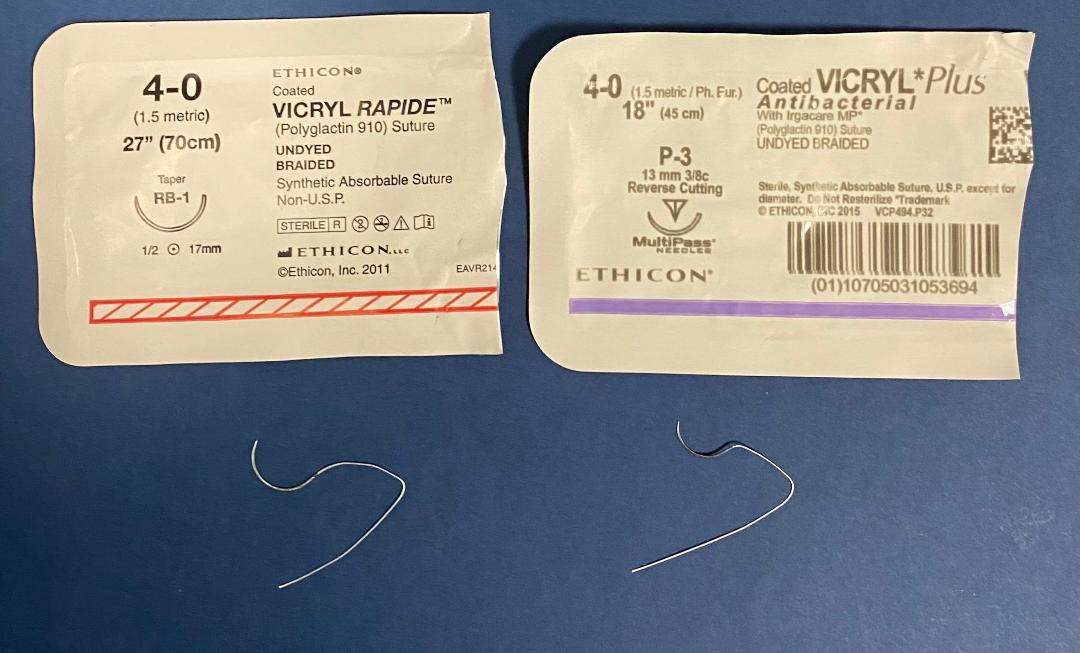

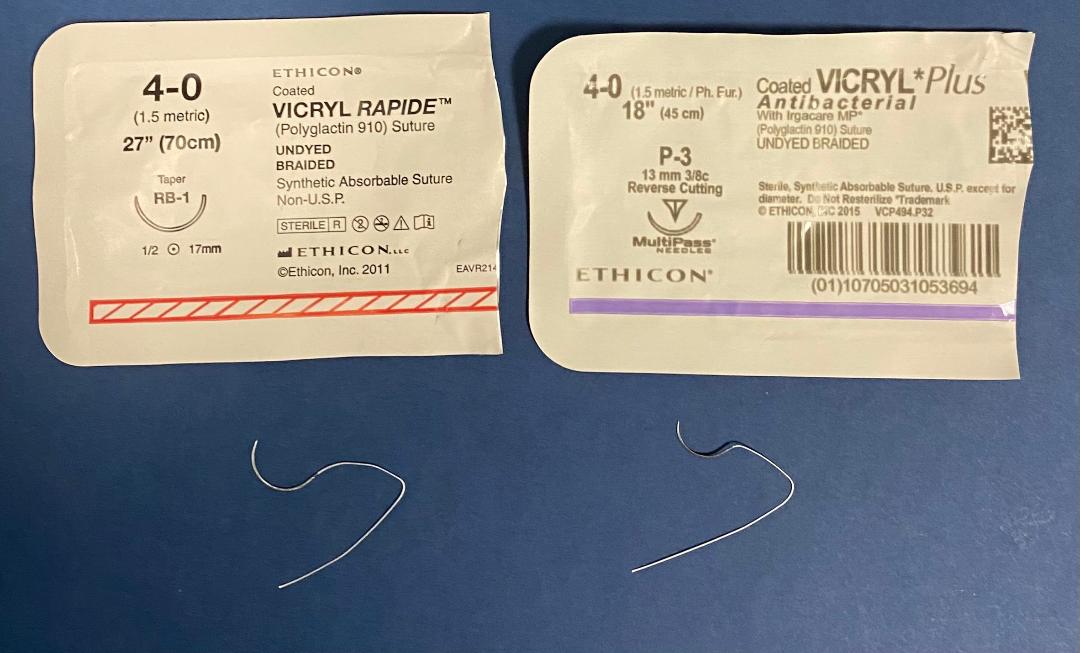

Vicryl Rapide and 'regular' Vicryl sutures look the same and feel the same when you're tying with them...but they are NOT the same sutures and they may NOT be used interchangeably.

Vicryl Rapide will lose its strength in only 7-10 days, unlike 'regular' Vicryl (~3 weeks).

Vicryl Rapide will lose its strength in only 7-10 days, unlike 'regular' Vicryl (~3 weeks).

Just to emphasize this point again and give examples:

'Regular' Vicryl sutures are fine for bowel anastomoses but Vicryl Rapide would definitely **NOT** be suitable.

Vicryl Rapide is good for closing certain skin incisions but 'regular' Vicryl would NOT be good for this.

'Regular' Vicryl sutures are fine for bowel anastomoses but Vicryl Rapide would definitely **NOT** be suitable.

Vicryl Rapide is good for closing certain skin incisions but 'regular' Vicryl would NOT be good for this.

In conclusion:

The sutures seen below are the most common 'rapidly' absorbable kinds. Many surgeons may never have occasion to use them, but some do.

There are a few sutures that are moderately fast absorbing (like Monocryl or Caprosyn), but none absorb as fast as these.

⬛️

The sutures seen below are the most common 'rapidly' absorbable kinds. Many surgeons may never have occasion to use them, but some do.

There are a few sutures that are moderately fast absorbing (like Monocryl or Caprosyn), but none absorb as fast as these.

⬛️

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh