The Olympic Theatre of Vicenza

On this day, the 3rd March 1585, the first permanent theatre to be built in the West since the days of Ancient Rome opened in the Italian city of Vicenza. How was this possible?

This is the story of a cultural and architectural resurrection 🧵 1/

On this day, the 3rd March 1585, the first permanent theatre to be built in the West since the days of Ancient Rome opened in the Italian city of Vicenza. How was this possible?

This is the story of a cultural and architectural resurrection 🧵 1/

The Italian Renaissance, in its most literal essence, was the move to rebirth and reinvent the classical world, whose architectural and artistic vestiges were emerging from the soils of medieval Rome. In its earliest days, it was a time of profound reckoning for the West. 2/

For the princes and scholars of Europe were faced with a humbling and intimidating realisation, that a civilisation far greater than their own had existed over a thousand years earlier, an Empire that was the progenitor of the world as we know it - Ancient Rome. 3/

Ever since Pompey the Great had erected the first stone theatre in Rome in 55 BC, from Britannia to Syria there would scarcely be a city in the Empire without one. The Romans, once sceptical of the 'Oriental corruption' they perceived in theatre, would elevate it to glory. 4/

With the fall of the Western Roman Empire in AD 476, volumes of human knowledge were lost. The classical arts faded into memory, the men of the West no longer knew how to build an arch, while theatres, viewed once more as dens of vice in Papal Rome, fell into disfavour. 5/

The early Church Fathers, and Saint Augustine in particular, railed against theatres, denouncing them as licentious offshoots of pagan temples. By telling the deeds of false gods, Augustine asserted, the theatres were "gratuitously fanning the flame of human lust". 6/

As a result, the building of theatres was near universally prohibited in Western Europe for much of the medieval era. Ironically, this merely resulted in the de facto censorship of 'sophisticated' productions, encouraging the spread of amateurish and bawdy 'undertheatre'. 7/

Yet by the 16th century, a love of learning flourished in Italy once more, buoyed by the wealth of knowledge saved from Constantinople in the wake of the Ottoman conquest of 1453, and breathtaking discoveries in the Eternal City herself, from sculptures to shattered temples. 8/

One of the greatest scions of this rebirth was a stonecutter's son from Padua, a man who would near single-handedly restore the built aesthetics of the West to their former glory. For what Michelangelo was to sculpture, Andrea Palladio was to architecture. 9/

As a young stonemason, Palladio's life was rather unremarkable until 1538, when while living in the Venetian city of Vicenza, he was employed by Gian Giorgio Trissino, a humanist scholar who had developed a fascination for the ancient texts of the Roman architect Vitruvius. 10/

Trissino, seeing in the young Palladio potential great indeed, took the young stonemason with him to Rome, there to observe the ruins of Antiquity with his own eyes. Palladio, dumbstruck, realised that the buildings of his day paled in comparison with what Rome had once been. 11/

Determined to learn the old ways, Palladio devoted the rest of his life to bringing this grandeur back from oblivion. Over the course of multiple sojourns in Rome and her hinterlands in the years to come, he studied all that he could, from ruins to forgotten texts. 12/

But when Andrea Palladio began to construct his own buildings, he did not only copy. Two qualities above all others graced his plans - a tightly mathematical approach to proportions, and an awareness of the surrounding landscape and how it could complement architecture. 13/

Over the next forty years, Andrea Palladio would immortalise the Renaissance in stone, gracing the Veneto with what are still today many of the most majestic works of architecture ever erected in the West, from the villas of the nobility to the churches of Venice. 14/

Fortunately for posterity, Palladio recorded his learned wisdom in his magnum opus, 'The Four Books of Architecture', a seminal treatise that would have profound implications for European architecture for centuries to come, and consolidate the 'built Renaissance'. 15/

A mark of this blossoming came in 1555 when Palladio, along with twenty other prominent citizens of Vicenza, built upon the legacy of Trissino and founded the Accademia Olimpica, or Olympic Academy, an independent learned society dedicated to the cultivation of the arts. 16/

Initially, Academy meetings rotated among the residences of its members, where theatrical performances were frequently staged in courtyards, halls, or wherever space could be found. Before long, however, the Academy sought more permanent premises. 17/

In 1580, the Academy received permission from the Vicentine authorities to construct a theatre on land formerly occupied, ironically, by the old prisons. For an architect, they needed look no further than their own - the now seventy two year old and highly revered Palladio. 18/

Now armed with decades of experience studying Roman ruins, and the wisdom contained within the treatise of Vitruvius - De architectura - Palladio planned the first permanent covered theatre Europe had seen in over a thousand years. 19/

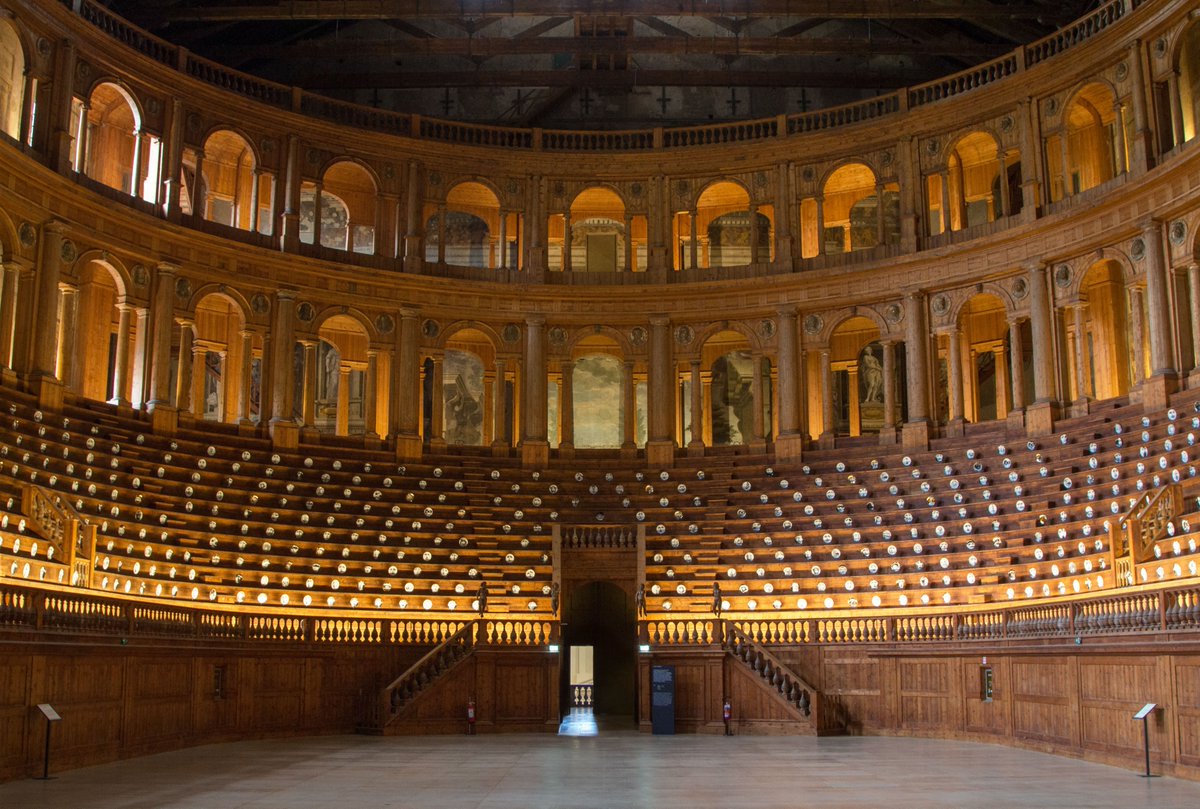

Paid for by donations by the academics themselves, immortalised now by the statues that overlook the auditorium, works progressed rapidly, and just as well - on the 19th August of the same year, Andrea Palladio died of old age, making the Theatre his final work. 20/

Fortunately for posterity, Vicenza had not pinned all of her cultural hopes on one man alone, and local architect Vincenzo Scamozzi, drawing on the work of both Palladio and Vitruvius, stepped in to take up the project with enthusiasm, alongside Palladio's son Silla. 21/

As a result, the death of Palladio proved an emotional, but not terminal blow to the Olympic Theatre, whose structure was largely completed in just three years, with her interior ready for the inaugural performance, to be held on the 3rd March 1585. 22/

It was for this grand occasion that Scamozzi crafted his most breathtaking contribution to the Theatre. With Oedipus Rex forming the inaugural production, Scamozzi reproduced the seven streets of the city of Thebes, unfurling behind the triumphal arch of the scaenae frons. 23/

Constructed of wood, it is a masterpiece of perspective. The streets appear to vanish into the distance, yet the stage is only seven metres deep. It is the oldest surviving theatre scenery in the Western world, having miraculously survived centuries of fire and war. 24/

The scenery indeed was only ever intended to be temporary, yet almost five centuries later, it stands in near perfect condition, such was the quality of the design and materials, while Scamozzi also designed the Odeon, and other spaces within the structure for the Academy. 25/

Following the triumphant opening, the fame of the Olympic Theatre spread to Venice and beyond, enduring even centuries later. Visiting on the 17th September 1786, Goethe lauded the "theatre based on the ancient model, but in small proportions and indescribably beautiful...". 26/

Even when the Counter Reformation would largely suppress performances within, the Theatre would regularly be used for occasions of state, receiving Pope Pius VI in 1782, as well as Emperors Francis I of Austria in 1816 and Ferdinand I in 1838. 27/

Over the centuries to come, the concept of a great European city lacking a permanent theatre of her own would be unthinkable. Monuments of entertainment, once considered scarcely better than brothels, were now objects of tremendous prestige, inseparable from high culture. 28/

Despite this, the Olympic Theatre of Vicenza, along with the Teatro all'Antica at Sabbioneta and the Teatro Farnese in Parma, is one of only three Renaissance theatres to survive into the 21st century, and still today both the Theatre and the Academy serve the city. 29/

For over four centuries, the Olympic Theatre has stood not only as an architectural wonder of Vicenza, but as an immortal testament to the determination of enlightened men that monumental beauty, and classical culture, need not be confined to the ancient past. 30/

If you enjoyed this thread, and indeed believe that this magnificent Theatre and the story behind it deserves broader recognition, please do consider sharing the first post here so we can help spread the word!

https://x.com/westernexile/status/1764303936759148924?s=20

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh