This is the Hawa Mahal in Jaipur, India.

Even though its name means "Palace of the Winds" it isn't actually a palace.

In truth, the Hawa Mahal is something much more interesting...

Even though its name means "Palace of the Winds" it isn't actually a palace.

In truth, the Hawa Mahal is something much more interesting...

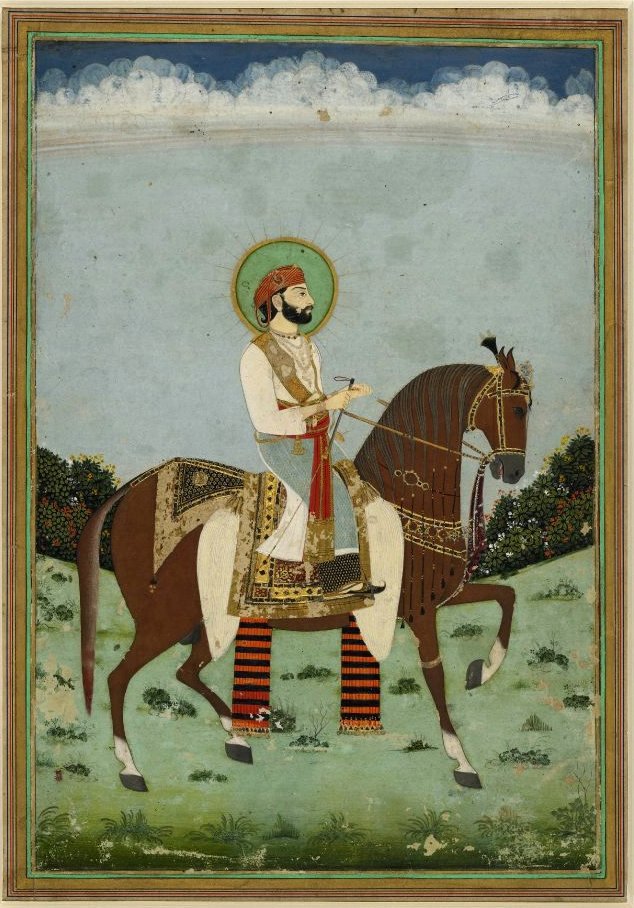

The year is 1699.

Sawai Jai Singh becomes ruler, or Maharaja, of the Kingdom of Amber in northern India.

He throws off the yoke of the Mughal Empire and establishes the independence of his kingdom, thus sparking a political and cultural revival.

Sawai Jai Singh becomes ruler, or Maharaja, of the Kingdom of Amber in northern India.

He throws off the yoke of the Mughal Empire and establishes the independence of his kingdom, thus sparking a political and cultural revival.

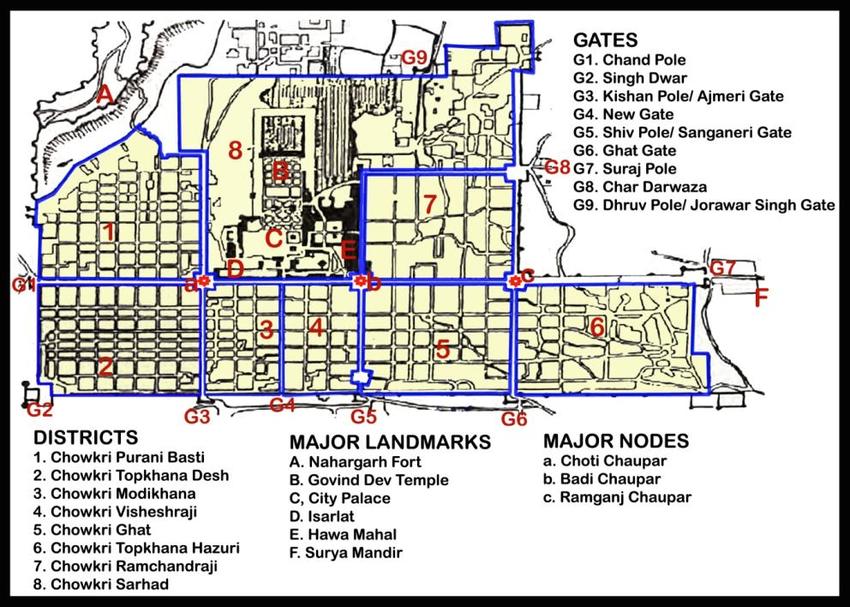

And in 1727 Sawai Jai Singh founded a new capital for his kingdom — Jaipur, meaning "City of Jai".

He employed a man called Vidyadhar Bhattacharya to plan this city according to ancient principles of Hindu architecture and urban design, known as Vastu Shastra.

He employed a man called Vidyadhar Bhattacharya to plan this city according to ancient principles of Hindu architecture and urban design, known as Vastu Shastra.

Sawai Jai Singh was an enlightened and civic minded ruler.

He commissioned translations of mathematical and astronomical texts into Sanskrit and had observatories built all across his kingdom.

Like the Jantar Mantar in Jaipur, a vast array of stone astronomical equipment.

He commissioned translations of mathematical and astronomical texts into Sanskrit and had observatories built all across his kingdom.

Like the Jantar Mantar in Jaipur, a vast array of stone astronomical equipment.

Sawai Jai Singh also renovated and redesigned the nearby Jal Mahal, a 17th century palace in the middle of a lake:

And then he built a ring of fortifications around the city, either creating new fortresses or renovating older ones built by the Mughals and other Rajput rulers.

There is the Amer Fort:

There is the Amer Fort:

And, for his royal residence, Sawai Jai Singh had the City Palace built.

It is a sprawling complex of buildings and courtyards added to and modified by successive rulers down the centuries:

It is a sprawling complex of buildings and courtyards added to and modified by successive rulers down the centuries:

You'll notice a trend with these buildings commissioned by Sawai Jai Singh — that they are made from a particularly delightful local limestone.

This has become a defining feature of Rajput architecture, along with, for example, the use of clustered miniature domes.

This has become a defining feature of Rajput architecture, along with, for example, the use of clustered miniature domes.

So Sawai Jai Singh created something special: a city with an architectural identity.

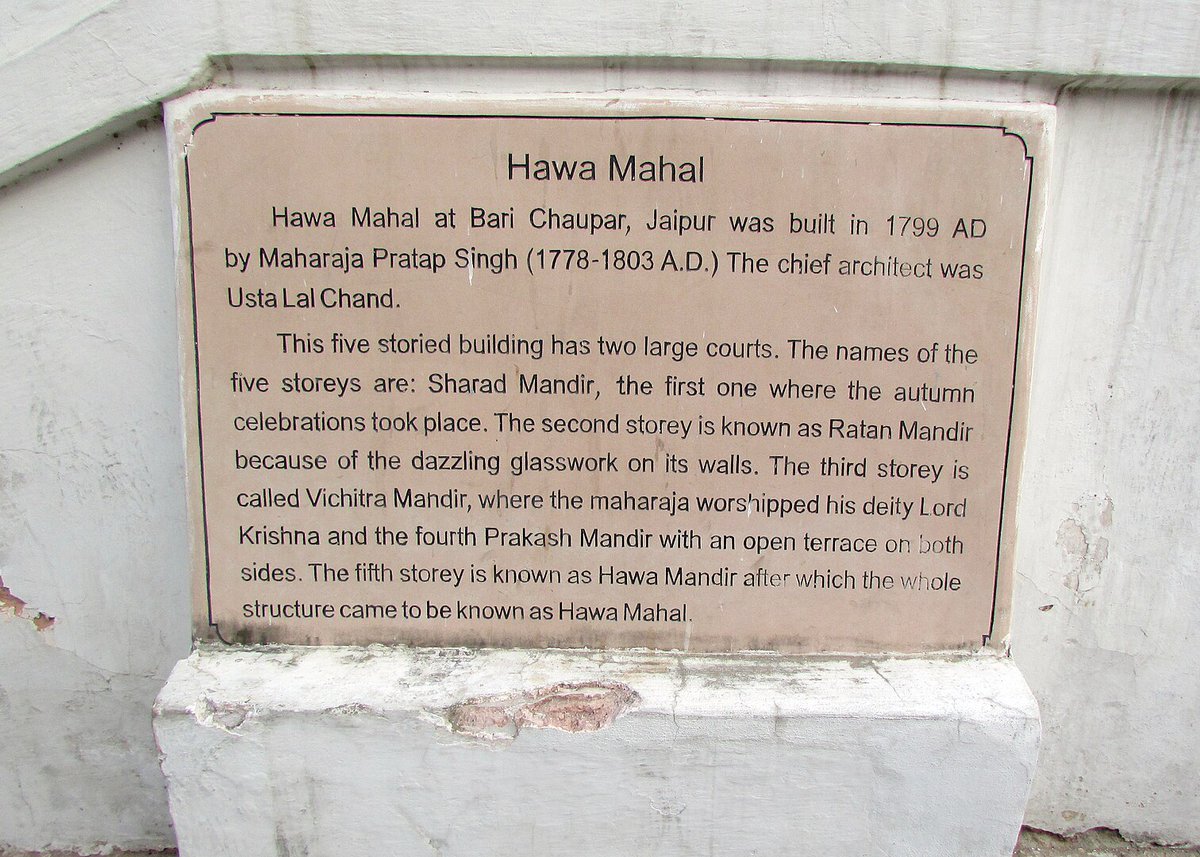

And it was his grandson, Sawai Pratap Singh, who commissioned its crowning jewel in 1799: the Hawa Mahal.

It was designed by Lal Chand Usta and shaped like the crown of Krishna.

And it was his grandson, Sawai Pratap Singh, who commissioned its crowning jewel in 1799: the Hawa Mahal.

It was designed by Lal Chand Usta and shaped like the crown of Krishna.

It's actually an extension to the rear of the City Palace built by Sawai Jai Singh, connected to the women's quarters.

Even though it looks like the grand front, notice that there is no doorway — we are looking at the back of the palace.

Even though it looks like the grand front, notice that there is no doorway — we are looking at the back of the palace.

Here is the entrace to the Hawa Mahal, within the grounds of the palace, and the large courtyard concealed behind its famous eastern exterior:

And so this is, in truth, a very unusual structure.

Though it looks like a grand set of chambers it is essentially a stack of galleries, a thin architectural screen, only a few feet wide at the top.

As you can see here:

Though it looks like a grand set of chambers it is essentially a stack of galleries, a thin architectural screen, only a few feet wide at the top.

As you can see here:

So, what is it?

The Hawa Mahal was built for the women of the City Palace, who had to keep themselves covered and were not allowed to mix with men.

It allowed them to observe city life, looking down on the street from any one of those 953 windows:

The Hawa Mahal was built for the women of the City Palace, who had to keep themselves covered and were not allowed to mix with men.

It allowed them to observe city life, looking down on the street from any one of those 953 windows:

And, architecturally, the Hawa Mahal has a lot going on.

It is designed around two prominent features of Indian architecture.

First, the jharokha, an ornate projecting window with its own hooded dome and finial — the jharokhas of the Hawa Mahal even have double or triple domes.

It is designed around two prominent features of Indian architecture.

First, the jharokha, an ornate projecting window with its own hooded dome and finial — the jharokhas of the Hawa Mahal even have double or triple domes.

And, secondly, the jali, a finely carved lattice made from either stone or wood — many of them are bafflingly elaborate works of art in their own right.

Before the widespread use of glass this is what served as a window.

Before the widespread use of glass this is what served as a window.

But jalis are not only aesthetic — the Venturi Effect means that when hot air flows through small openings it cools down.

So they were a form of pre-modern air conditioning (hence their prevalence in Indo-Islamic architecture) in this case keeping the women of the palace cool.

So they were a form of pre-modern air conditioning (hence their prevalence in Indo-Islamic architecture) in this case keeping the women of the palace cool.

And notice how the Hawa Mahal becomes more complex with each ascending storey.

Jalis become finer, jharokhas more ornate, domes and finials more numerous.

This is subtle, but it transforms what might have been monotonous into a delightfully varied masterpiece of facade design.

Jalis become finer, jharokhas more ornate, domes and finials more numerous.

This is subtle, but it transforms what might have been monotonous into a delightfully varied masterpiece of facade design.

And, again, this wasn't only aesthetic.

The varying sizes of the windows and lattices were intended for different seasons, as temperatures varied throughout the year — the Hawa Mahal was a miracle of climate control.

Each of the floors also has its own name:

The varying sizes of the windows and lattices were intended for different seasons, as temperatures varied throughout the year — the Hawa Mahal was a miracle of climate control.

Each of the floors also has its own name:

And, of course, the Hawa Mahal was built with that famous local limestone, glowing when illuminated by the sun and perfectly contrasting with the white windows and decorations.

A reminder that the materials and colours we use are a vital part of architecture.

A reminder that the materials and colours we use are a vital part of architecture.

So that's the unusual and fabulous Hawa Mahal, which has come to symbolise Rajput architecture.

But it all started with Sawai Jai Singh — the Hawa Mahal came from the virtuous circle he created by founding Jaipur and funding its architecture.

An important lesson for the future.

But it all started with Sawai Jai Singh — the Hawa Mahal came from the virtuous circle he created by founding Jaipur and funding its architecture.

An important lesson for the future.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh