On this day 2,068 years ago Julius Caesar was assassinated in broad daylight in the middle of Rome.

But it wasn't a mob or popular uprising — Caesar was killed by a group of disgruntled senators.

Here's how it happened, moment by moment, on that fateful day in 44 BC...

But it wasn't a mob or popular uprising — Caesar was killed by a group of disgruntled senators.

Here's how it happened, moment by moment, on that fateful day in 44 BC...

The year is 44 BC. Julius Caesar has been declared "Dictator for Life" and is now the most powerful man in the Roman Republic.

In 48 BC he had defeated Pompey the Great, another Roman general, and by 45 BC he had put down all resistance.

The civil wars were over; peace at last.

In 48 BC he had defeated Pompey the Great, another Roman general, and by 45 BC he had put down all resistance.

The civil wars were over; peace at last.

But a conspiracy was brewing.

The Senators were worried by how much power Caesar had amassed and — crucially — by how much the people loved him.

They feared that, if he hadn't already, Caesar would soon turn the Roman Republic into a kingdom ruled by one man.

The Senators were worried by how much power Caesar had amassed and — crucially — by how much the people loved him.

They feared that, if he hadn't already, Caesar would soon turn the Roman Republic into a kingdom ruled by one man.

So this was not an uprising of the people against a tyrant — it was a small conspiracy of aristocrats and senators, about sixty of them in all.

Why did they want to kill Caesar? There are two views.

The first is that they wanted to save the Republic from a populist tyrant.

Why did they want to kill Caesar? There are two views.

The first is that they wanted to save the Republic from a populist tyrant.

Marcus Junius Brutus was the reluctant leader of this conspiracy. He had been on Pompey's side during the Civil War, but Caesar had granted him amnesty.

Brutus was conflicted between betraying the man who saved his life and protecting the sacred, ancient Roman Republic.

Brutus was conflicted between betraying the man who saved his life and protecting the sacred, ancient Roman Republic.

The less idealistic view is that these Senators' political position was threatened by Caesar, who didn't need their support and might circumvent them completely.

Rather than Brutus' lofty and noble ambitions, perhaps the conspiracy was simply a question of power.

Rather than Brutus' lofty and noble ambitions, perhaps the conspiracy was simply a question of power.

Either way, momentum reached fever pitch.

Too many people knew about the conspiracy; it would soon be uncovered; time was running out.

They considered killing him at the elections in the Campus Martius, but then Caesar announced a special Senate meeting on the Ides of March.

Too many people knew about the conspiracy; it would soon be uncovered; time was running out.

They considered killing him at the elections in the Campus Martius, but then Caesar announced a special Senate meeting on the Ides of March.

In the Roman calendar there were three dates in each month with special names.

For months with 31 days the 1st was called the Kalends, the 7th was called the Nones, and the 15th was called the Ides.

(For months with 30 days the Nones and Ides came two days earlier.)

For months with 31 days the 1st was called the Kalends, the 7th was called the Nones, and the 15th was called the Ides.

(For months with 30 days the Nones and Ides came two days earlier.)

The great Greek historian Plutarch noted the irony that it was at the Curia of Pompey, built by Caesar's greatest rival, that this meeting of the Senate was scheduled to take place.

The Curia was by the entrance of a large theatre also built by Pompey.

The Curia was by the entrance of a large theatre also built by Pompey.

Nor was that the only twist of fate.

When Rome had been ruled by kings it was another Brutus who led the coup in 509 BC and established the Roman Republic.

Five hundred years later his descendent would try to save it.

When Rome had been ruled by kings it was another Brutus who led the coup in 509 BC and established the Roman Republic.

Five hundred years later his descendent would try to save it.

It is the morning of the Ides of March, the 15th.

Brutus, dagger under his robe, leaves his wife Porcia for the meeting — she begs him not to go, terrified that it will end badly.

But he does. So the conspirators gather at the Curia of Pompey, waiting, waiting, waiting...

Brutus, dagger under his robe, leaves his wife Porcia for the meeting — she begs him not to go, terrified that it will end badly.

But he does. So the conspirators gather at the Curia of Pompey, waiting, waiting, waiting...

Caesar is late.

He remains at home all morning because of bad health, strange dreams, and troubling omens over the last few days.

Caesar is spooked and — urged by his wife — sends his right-hand man Mark Antony to postpone the Senate meeting.

He remains at home all morning because of bad health, strange dreams, and troubling omens over the last few days.

Caesar is spooked and — urged by his wife — sends his right-hand man Mark Antony to postpone the Senate meeting.

But Decimus Albinus, another of Caesar's allies, is part of the plot.

He reminds Caesar that it was he who called the meeting, and suggests the Senate intend to proclaim him king if he shows up.

Not to go would be an insult — and, to the people, it might make him look weak.

He reminds Caesar that it was he who called the meeting, and suggests the Senate intend to proclaim him king if he shows up.

Not to go would be an insult — and, to the people, it might make him look weak.

Meanwhile, back at the Curia, the conspirators are barely hold their nerve.

Had the plot been revealed?

Had the plot been revealed?

Caesar is coming.

Allegedly a soothsayer called Spurinna once told Caesar to "beware the Ides of March." On his way to the Senate Caesar sees Spurinna and mocks his prophecy, saying, "the Ides have come."

Spurinna replies, "they have come, but not yet gone."

Allegedly a soothsayer called Spurinna once told Caesar to "beware the Ides of March." On his way to the Senate Caesar sees Spurinna and mocks his prophecy, saying, "the Ides have come."

Spurinna replies, "they have come, but not yet gone."

Meanwhile Brutus receives a message to say his wife has died. She hadn't, as he later discovered, but he decides to remain anyway.

Finally Caesar arrives at the Curia.

But not without one final moment of panic, as the conspirators fear they are being outed:

Finally Caesar arrives at the Curia.

But not without one final moment of panic, as the conspirators fear they are being outed:

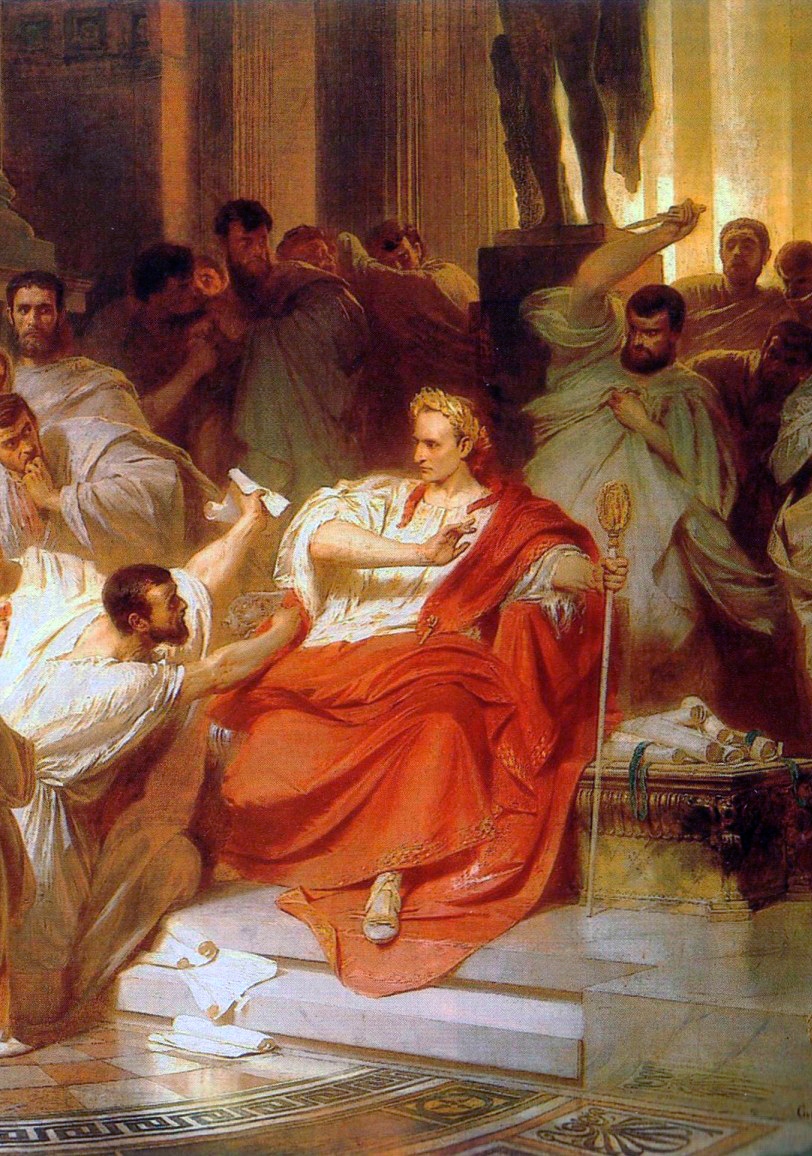

Caesar enters the Curia.

Mark Antony is a fierce soldier who might have been able to protect him — Albinus delays Mark Antony outside; this was a crucial part of the plan.

Inside, Caesar is slowly surrounded by the Senators...

Mark Antony is a fierce soldier who might have been able to protect him — Albinus delays Mark Antony outside; this was a crucial part of the plan.

Inside, Caesar is slowly surrounded by the Senators...

And then it happens.

Caesar is overwhelmed and cannot defend himself; he is stabbed twenty three times, saying nothing... until he realises Brutus is one of his attackers:

Caesar is overwhelmed and cannot defend himself; he is stabbed twenty three times, saying nothing... until he realises Brutus is one of his attackers:

The conspirators leave his body and the next stage of their plan commences: to address the people, assuage their fears, establish order, and proclaim liberty for the Republic.

That is how they refer to themselves — as Liberators.

That is how they refer to themselves — as Liberators.

But Rome is eerily silent — the conspirators disperse and barricade themselves at home.

Next day Brutus addresses the people. It goes well until Caesar's will is read by Mark Antony — he has left money to every single citizen.

A riot breaks out and the Curia is burned down.

Next day Brutus addresses the people. It goes well until Caesar's will is read by Mark Antony — he has left money to every single citizen.

A riot breaks out and the Curia is burned down.

Antony's plan works perfectly.

The conspirators believe the people are against them and scale back their hopes for reform.

Antony urges peace, calms the people, and agrees a compromise whereby the conspirators are not punished but Caesar's laws and reforms remain valid.

The conspirators believe the people are against them and scale back their hopes for reform.

Antony urges peace, calms the people, and agrees a compromise whereby the conspirators are not punished but Caesar's laws and reforms remain valid.

But civil war eventually broke out and the conspirators were defeated in 42 BC by Mark Antony and Octavian, Caesar's heir.

After that came yet another civil war between Antony and Octavian.

Octavian won and in 27 BC became Augustus, the first Emperor — thus ensued Pax Romana.

After that came yet another civil war between Antony and Octavian.

Octavian won and in 27 BC became Augustus, the first Emperor — thus ensued Pax Romana.

The reputation of Caesar's assassins is mixed.

Many — even Romans — regarded Brutus as a symbol of liberty and courage.

But in Dante's Divine Comedy Brutus and Cassius are in the deepest part of Hell, eternally devoured alive in one of Satan's three mouths alongside Judas.

Many — even Romans — regarded Brutus as a symbol of liberty and courage.

But in Dante's Divine Comedy Brutus and Cassius are in the deepest part of Hell, eternally devoured alive in one of Satan's three mouths alongside Judas.

Whether Brutus was treacherous or noble, his plans failed — the Republic fell and Rome became an Empire.

So that's the 15th March 44 BC, one of those dates forever etched into the annals of history.

And the question remains: was Brutus a hero or a villain?

So that's the 15th March 44 BC, one of those dates forever etched into the annals of history.

And the question remains: was Brutus a hero or a villain?

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh