views

The FBI raided Jeni Pearson's safe deposit box and tried to take all the contents using civil forfeiture. Jeni fought back, along with other @IJ clients, and won...

Except, when the FBI returned the box contents, $2,000 was missing. So Jeni and @IJ sued again.

Yesterday, we got an important decision in our case seeking to recover Jeni's $2,000.

Except, when the FBI returned the box contents, $2,000 was missing. So Jeni and @IJ sued again.

Yesterday, we got an important decision in our case seeking to recover Jeni's $2,000.

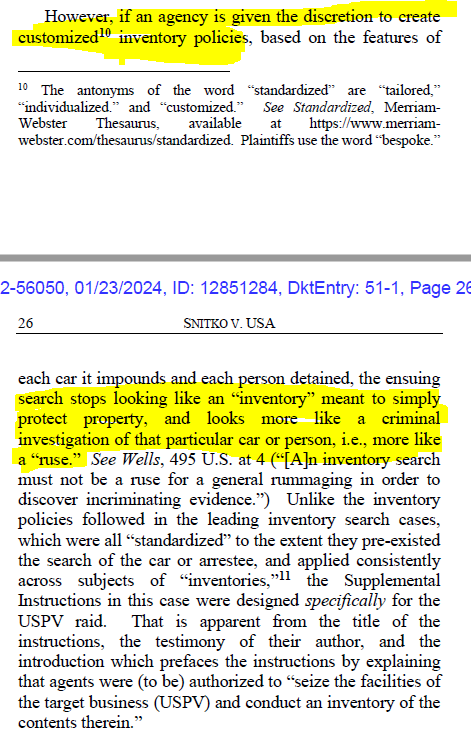

Jeni's fight for her missing $2,000 is another chapter in the story of U.S. Private Vaults, a safe deposit box facility in Beverly Hills that the FBI raided in March 2021. @IJ challenged the raid, and, earlier this year, the Ninth Circuit held that the raid violated the Fourth Amendment.

https://x.com/FreeRangeLawyer/status/1732134813715353913?s=20

So, how does Jeni know that $2,000 went missing from her box?

Whenever she visited the box, she took a picture of the contents. And, when she visited the box in February 2021--just a month before the raid--she took a picture of the cash.

But when the FBI returned the contents of the box, there was no cash at all.

Whenever she visited the box, she took a picture of the contents. And, when she visited the box in February 2021--just a month before the raid--she took a picture of the cash.

But when the FBI returned the contents of the box, there was no cash at all.

When Jeni sued, the government argued there was literally no remedy for the loss of her $2,000.

The government invoked a doctrine called "sovereign immunity" -- the idea that you can't sue the government for damages.

And, when Jeni also sued the individual officers involved in the raid, the government argued that there is no way to hold government officials liable for violating your constitutional rights.

The government invoked a doctrine called "sovereign immunity" -- the idea that you can't sue the government for damages.

And, when Jeni also sued the individual officers involved in the raid, the government argued that there is no way to hold government officials liable for violating your constitutional rights.

@IJ Yesterday, the district court rejected that argument.

The Takings Clause bars the government from taking private property without just compensation. That means, if the government takes your $2,000 and never gives it back, the government has to compensate you for the loss.

The Takings Clause bars the government from taking private property without just compensation. That means, if the government takes your $2,000 and never gives it back, the government has to compensate you for the loss.

So, now the case moves forward to discovery -- meaning we get to ask the FBI some uncomfortable questions about what exactly happened to the missing $2,000. I literally couldn't be looking forward to that more.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh