This city is not in Italy, France, or Germany.

It's in China and it's less than ten years old.

This is Huawei's R&D Headquarters, where 25,000 people work, and it might just be the most interesting office building(s) in the world...

It's in China and it's less than ten years old.

This is Huawei's R&D Headquarters, where 25,000 people work, and it might just be the most interesting office building(s) in the world...

Officially called the "Huawei Ox Horn Campus", this vast complex — essentially a small city — was built between 2015 and 2022 to the cost of $1.5 billion in Dongguan, Guangdong Province, southern China.

It covers 1.4 million square metres and accommodates 25,000+ employees.

It covers 1.4 million square metres and accommodates 25,000+ employees.

The Campus is divided into twelve sections inspired by cities or regions in Europe, plus 1-1 replicas of famous buildings.

They are: Paris, Oxford, Bruges, Burgundy, Fribourg, Luxembourg, Windermere, Granada, Verona, Český Krumlov, Heidelberg, and Bologna (pictured below).

They are: Paris, Oxford, Bruges, Burgundy, Fribourg, Luxembourg, Windermere, Granada, Verona, Český Krumlov, Heidelberg, and Bologna (pictured below).

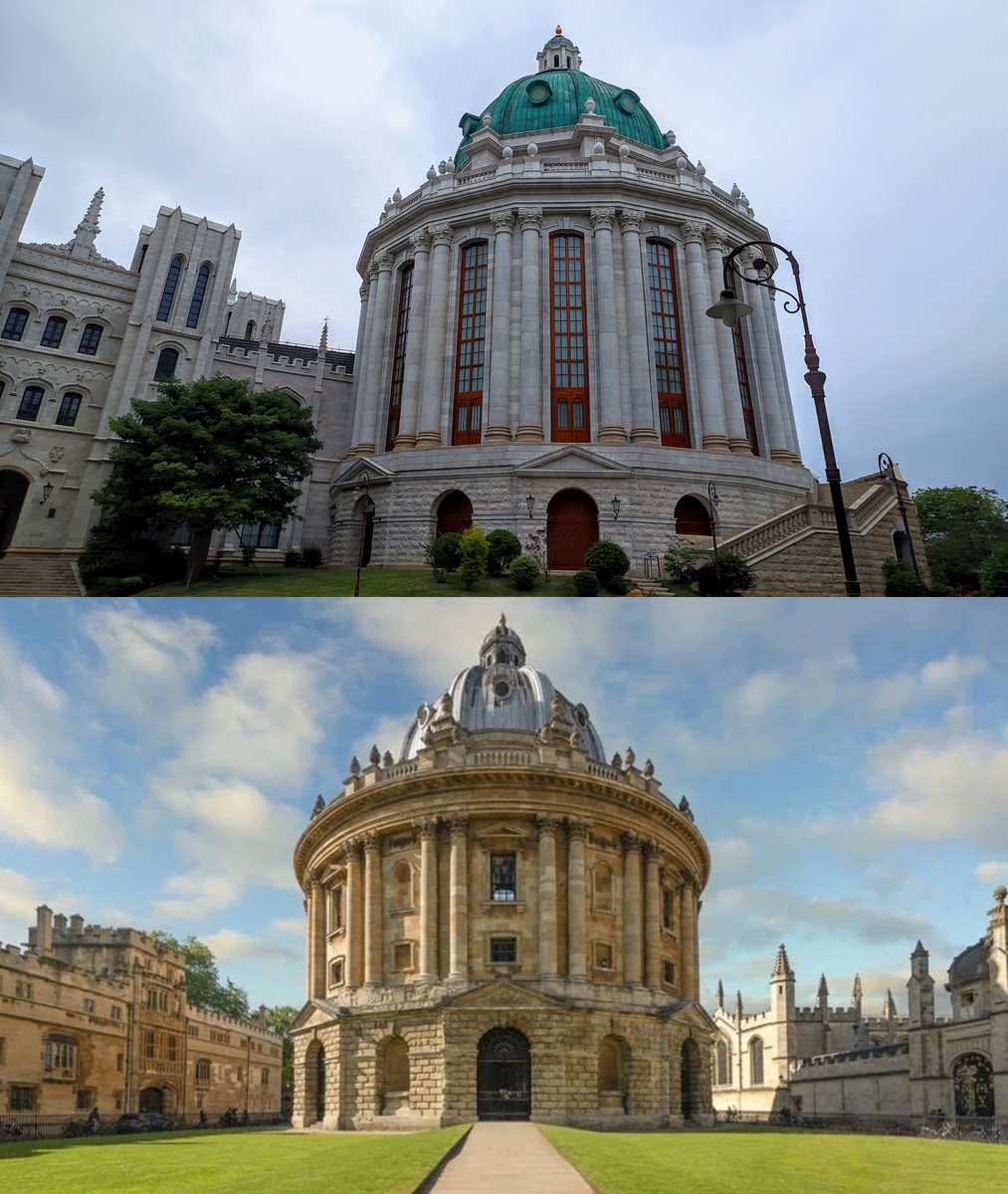

Here we see the famous Radcliffe Camera at Oxford University, built in the 18th century, and its replica at Ox Horn Campus:

And here is the star of the show — a reinterpretation of Heidelberg Castle in Germany, which stands at the heart of the Campus.

The lake below and the meadows and forests around it are the "Windermere" section, named after England's largest lake.

The lake below and the meadows and forests around it are the "Windermere" section, named after England's largest lake.

The Old Bridge in Heidelberg, with its distinctive gateway at one end, has also been rebuilt by Huawei:

There is also a reinterpretation of Versailles in France.

Remember: these buildings are brand new, and in many cases filled with high-tech equipment and research facilities.

It may look like a museum or palace, but this is a state of the art workplace.

Remember: these buildings are brand new, and in many cases filled with high-tech equipment and research facilities.

It may look like a museum or palace, but this is a state of the art workplace.

Inside is a replica of the Reading Room at France's National Library, complete with a colossal stained glass ceiling.

You can see how Huawei's versions are less lavish, slightly less detailed than the originals.

Still, it's hard to argue they did a bad job.

You can see how Huawei's versions are less lavish, slightly less detailed than the originals.

Still, it's hard to argue they did a bad job.

And in the Bruges section there is even a replica of Bruges' famous Belfry.

You also get a sense of how Ox Horn Campus has streets, alleys, and squares, just like any real city.

Rather than going up elevators you walk through narrow lanes — a novel approach to office design?

You also get a sense of how Ox Horn Campus has streets, alleys, and squares, just like any real city.

Rather than going up elevators you walk through narrow lanes — a novel approach to office design?

Large parts of Verona in northern Italy have been rebuilt by Huawei.

Including the great Castelvecchio on the banks of the Adige, built during the reign of the Scaliger Dynasty in Verona.

Notice, to the left of Huawei's version, the towers of Czechia's Český Krumlov.

Including the great Castelvecchio on the banks of the Adige, built during the reign of the Scaliger Dynasty in Verona.

Notice, to the left of Huawei's version, the towers of Czechia's Český Krumlov.

And the Torre dei Lamberti, the tallest building in Verona, constructed between the 12th and 15th centuries:

Even the building adjacent to the Torre dei Lamberti, the Palazzo della Ragione, has been built by Huawei, along with the so-called "Staircase of Reason" in its courtyard.

Plus the distinctive red and white stripes of brick and tufa used in Medieval Veronese architecture.

Plus the distinctive red and white stripes of brick and tufa used in Medieval Veronese architecture.

In the section inspired by Burgundy there is a replica of Fontenay Abbey, a miracle of Romanesque architecture, along with the walls and towers of the town of Semur-en-Auxois:

And in the section inspired by Fribourg, Switzerland, there is a version of the Berntor Clocktower in Murton.

The whole campus is on a much more human scale than most modern office buildings; is there something to be learned here?

The whole campus is on a much more human scale than most modern office buildings; is there something to be learned here?

The examples go on and on — there are more than one hundred buildings at Ox Horn.

And, it seems, they were chosen tastefully: these may be famous buildings, but they are hardly "iconic" structures like the Eiffel Tower.

A genuinely broad and interesting choice of architectures.

And, it seems, they were chosen tastefully: these may be famous buildings, but they are hardly "iconic" structures like the Eiffel Tower.

A genuinely broad and interesting choice of architectures.

The whole campus is linked by an electric tram system nearly 8km in length — each of the twelve "towns" has at least one tram station.

The idea was to make it a car-free town.

The trams themselves were modelled on the carriages of Switzerland's legendary Jungfrau Railway:

The idea was to make it a car-free town.

The trams themselves were modelled on the carriages of Switzerland's legendary Jungfrau Railway:

Each section also has cafes, restaurants, shops, gyms, and other amenities — including rather grand dining halls like this one in the Bologna section.

This probably isn't what you associate with the world's largest manufacturer of telecommunications equipment.

This probably isn't what you associate with the world's largest manufacturer of telecommunications equipment.

All in all, then, Ox Horn Campus is quite the project.

It has been criticised within China for borrowing foreign styles rather than being based on traditional Chinese architecture — meanwhile critics abroad have called it kitsch, vulgar, and even "fake".

It has been criticised within China for borrowing foreign styles rather than being based on traditional Chinese architecture — meanwhile critics abroad have called it kitsch, vulgar, and even "fake".

"Fake" is surely a snobbish criticism; what's wrong with recreating beloved architecture from the past?

And, besides, not everybody can travel around the world — why shouldn't architecture do the travelling instead?

Like Prague's Charles Bridge:

And, besides, not everybody can travel around the world — why shouldn't architecture do the travelling instead?

Like Prague's Charles Bridge:

And, in a world where the vast majority of offices are identical skyscrapers, and most of them extremely boring, Huawei's traditionally-inspired campus is actually a rather bold and imaginative decision.

Is this really "fake"? Or is it more appealing than most office spaces?

Is this really "fake"? Or is it more appealing than most office spaces?

And, most interesting of all, it flies in the face of the argument that older architectural styles are no longer practical, affordable, or possible.

Huawei built Ox Horn using modern construction methods without compromising the styles they sought to evoke — even lamp posts.

Huawei built Ox Horn using modern construction methods without compromising the styles they sought to evoke — even lamp posts.

Huawei borrowed European architecture for Ox Horn Campus — could Europe borrow something in return?

This project shows what is possible with just a little bit of imagination and desire.

Would people be happier if they worked in places like this?

This project shows what is possible with just a little bit of imagination and desire.

Would people be happier if they worked in places like this?

So... is it fake or is it charming? Is it old-fashioned or is it forwards-thinking?

At the very least, Ox Horn Campus shows that not all offices have to look the same, that glass boxes are not our only option.

Would you want to work in an office like this, or not?

At the very least, Ox Horn Campus shows that not all offices have to look the same, that glass boxes are not our only option.

Would you want to work in an office like this, or not?

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh