When 460 knots just isn't fast enough...

We've been cruising the globe at basically the same speed since the 1960s. Faster would be nicer, so what are the challenges facing hypersonic airliners?

Read on...

We've been cruising the globe at basically the same speed since the 1960s. Faster would be nicer, so what are the challenges facing hypersonic airliners?

Read on...

The speed of sound is the maximum speed that a pressure wave or vibration can pass through a substance. It varies with material & temperature.

Mach 1 is a speed equivalent to the local speed of sound. Airliners cruise at around Mach 0.85.

Hypersonic is above Mach 5-ish.

Mach 1 is a speed equivalent to the local speed of sound. Airliners cruise at around Mach 0.85.

Hypersonic is above Mach 5-ish.

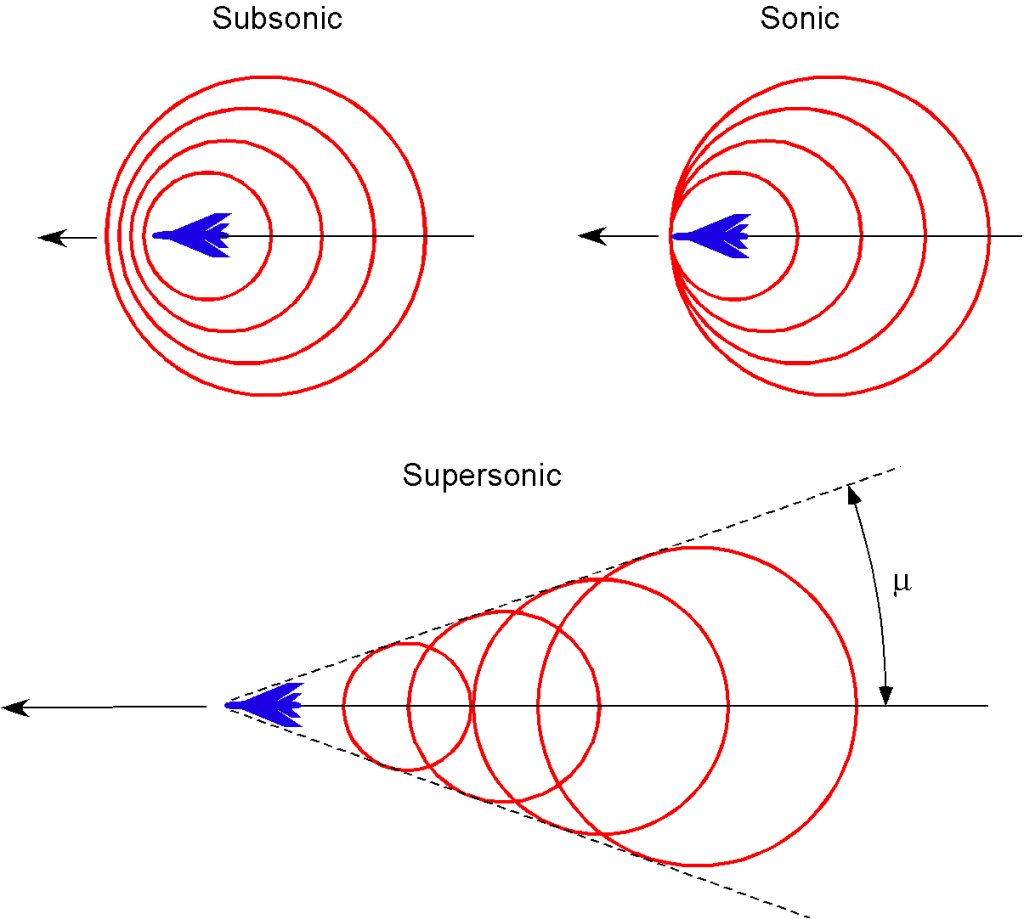

At subsonic speeds, pressure effects propagate ahead of the aircraft and airflow starts to react to the aircraft before it reaches it.

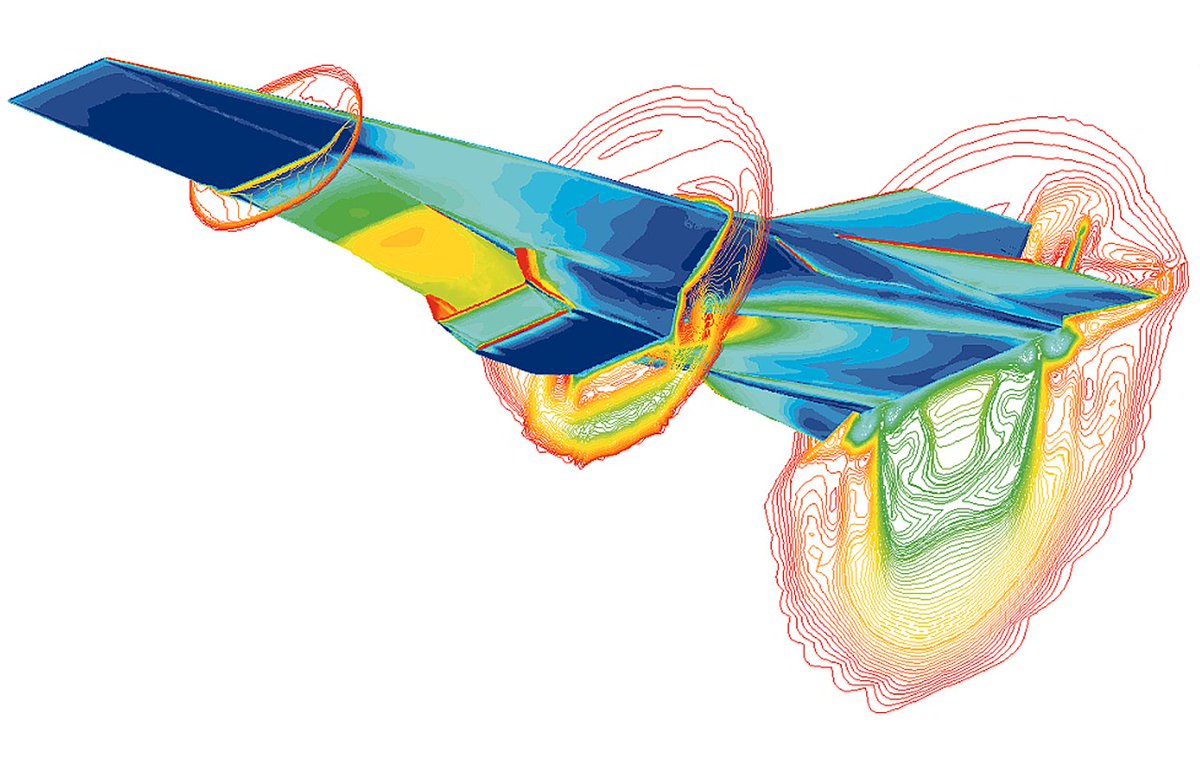

At supersonic speeds this isn't possible, and shockwaves form, with sharp temperature, pressure & density gradients. This is compressible flow.

At supersonic speeds this isn't possible, and shockwaves form, with sharp temperature, pressure & density gradients. This is compressible flow.

Because pressure waves only communicate at Mach 1, the flow behind a shock wave is subsonic in the direction perpendicular to the shock.

This means that as freestream Mach increases, the shock wave angle tightens around the aircraft.

This means that as freestream Mach increases, the shock wave angle tightens around the aircraft.

Shocks squeeze and heat the air. Hypersonic flow is fast enough that real gas effects & heating under compression start to dominate, heating becomes extreme, and effects such as thermally driven chemical changes start to play a part.

Hypersonic aerodynamics = aeroTHERMOdynamics

Hypersonic aerodynamics = aeroTHERMOdynamics

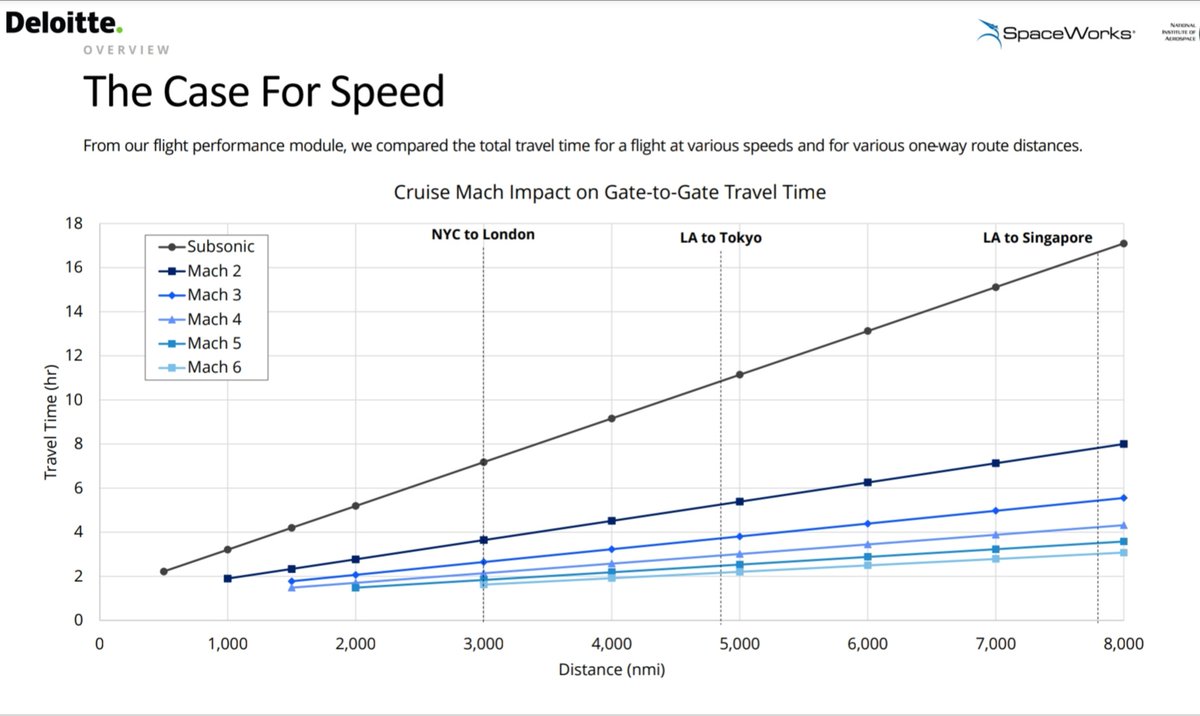

How valuable is speed?

Very: Go fast enough and long distance round trips become a single-day affair, saving days.

But acceleration and climb takes time, so a too-high VMax means no time spent cruising. After Mach 5, benefits are almost nil.

Very: Go fast enough and long distance round trips become a single-day affair, saving days.

But acceleration and climb takes time, so a too-high VMax means no time spent cruising. After Mach 5, benefits are almost nil.

Propulsion problems.

What gets you from 0 to Mach 5? A rocket, but it has to carry both fuel & oxidiser, so it's specific impulse (a fuel efficiency measure, proportional to thrust/ propellant flow) is very low.

Airliners need high Isp, so we have to use multiple engine cycles

What gets you from 0 to Mach 5? A rocket, but it has to carry both fuel & oxidiser, so it's specific impulse (a fuel efficiency measure, proportional to thrust/ propellant flow) is very low.

Airliners need high Isp, so we have to use multiple engine cycles

Why?

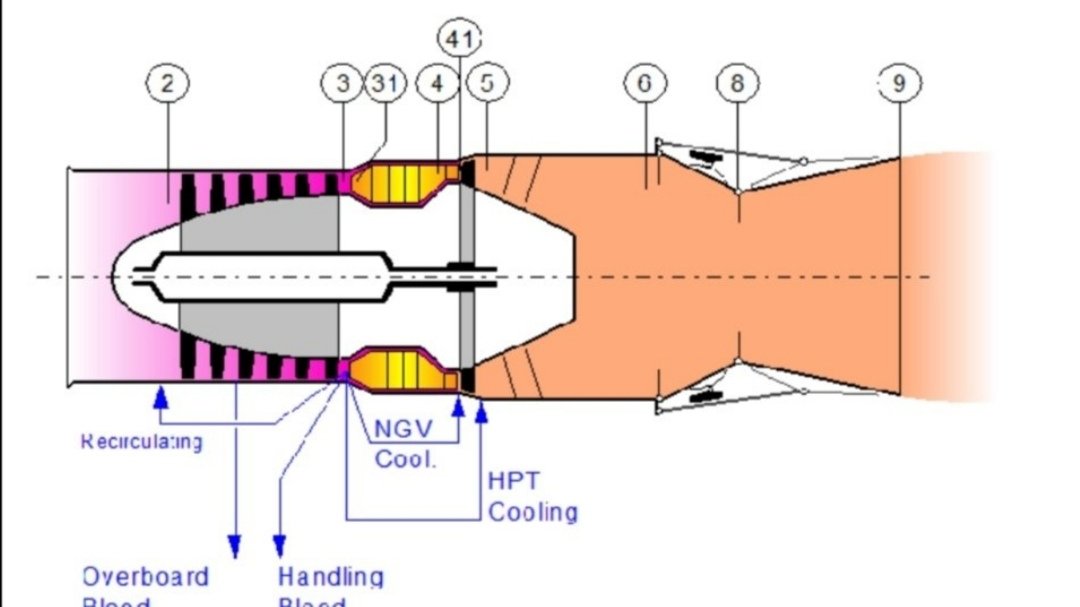

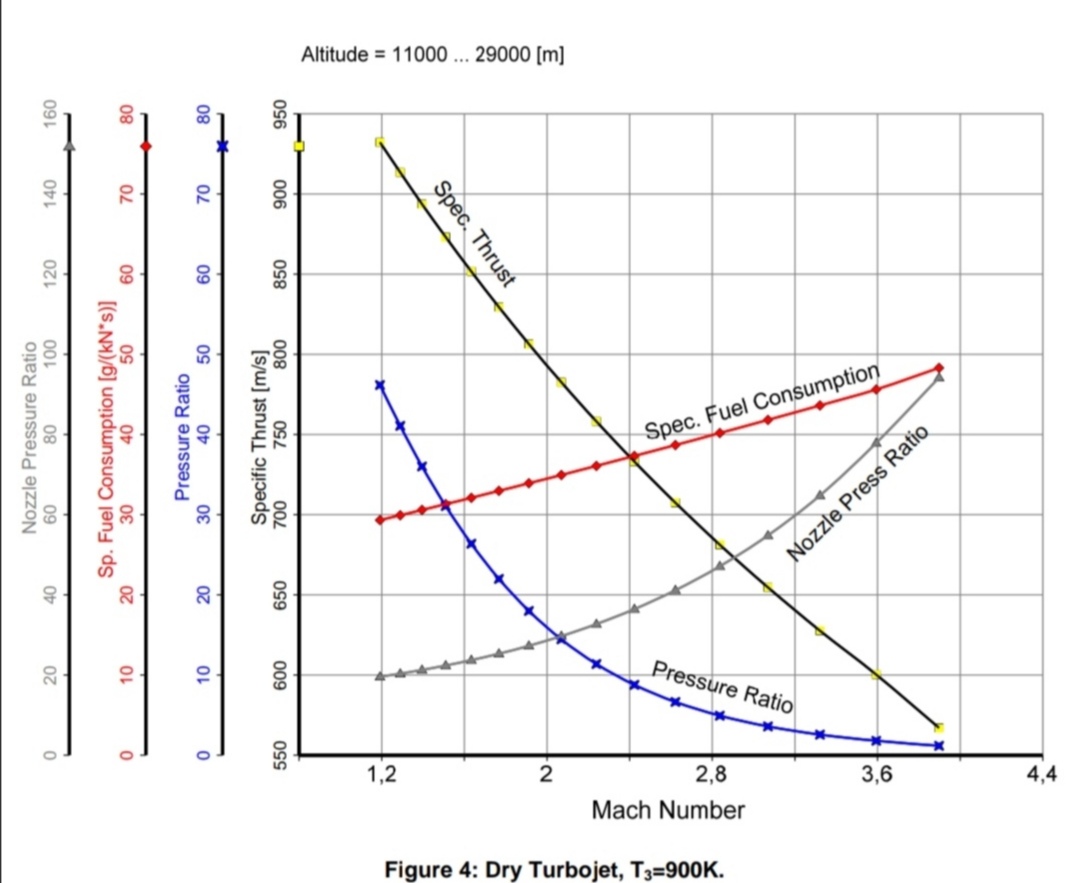

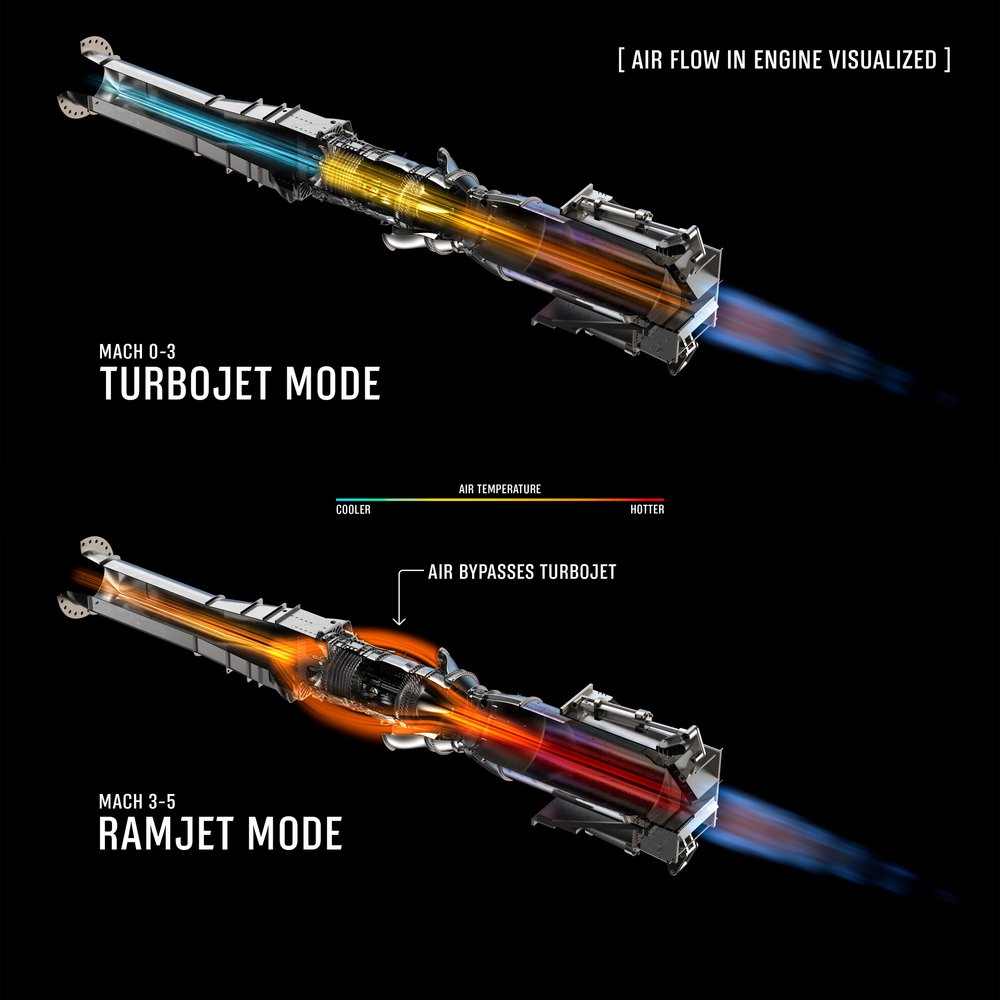

A turbojet has to "suck, squeeze, bang, blow": Incoming air needs to be decelerated to subsonic speeds before compression & combustion, and all that kinetic energy in the air has to go somewhere, so the air heats up.

A turbojet has to "suck, squeeze, bang, blow": Incoming air needs to be decelerated to subsonic speeds before compression & combustion, and all that kinetic energy in the air has to go somewhere, so the air heats up.

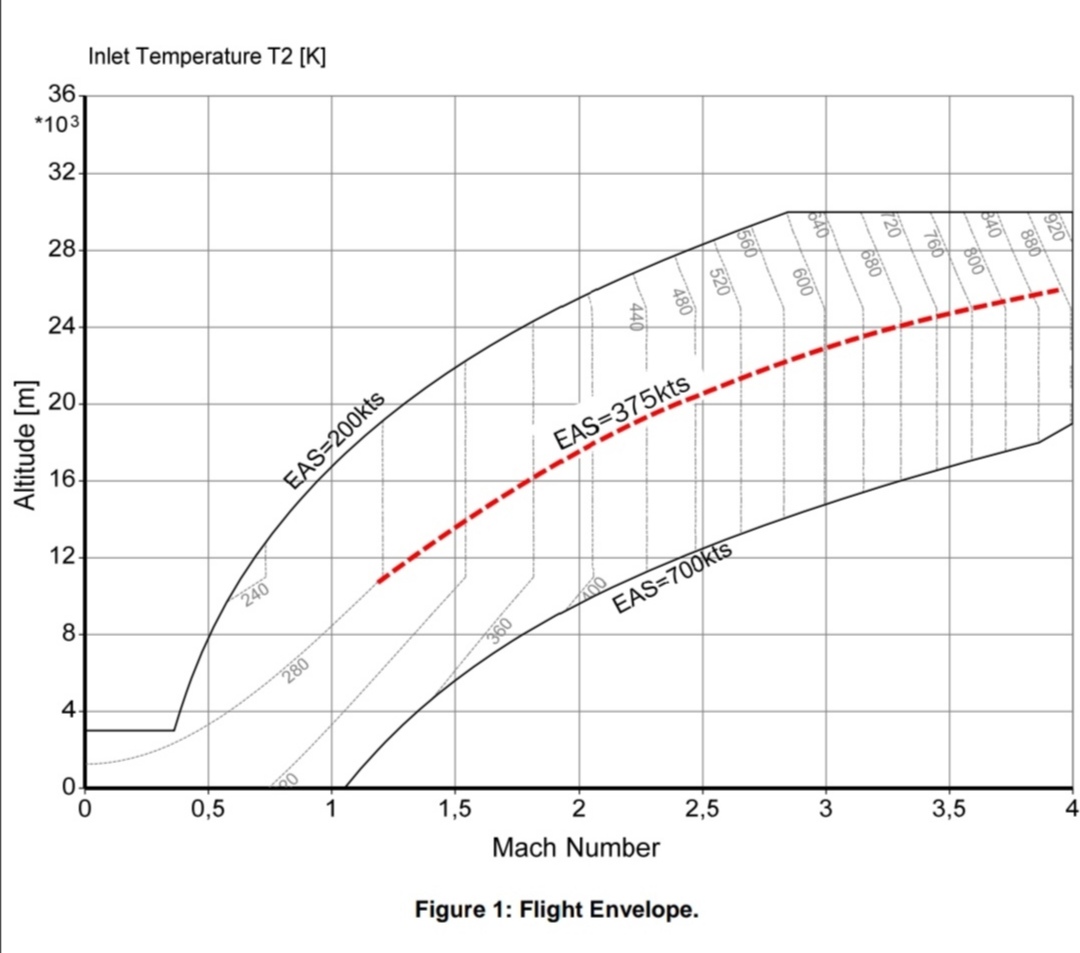

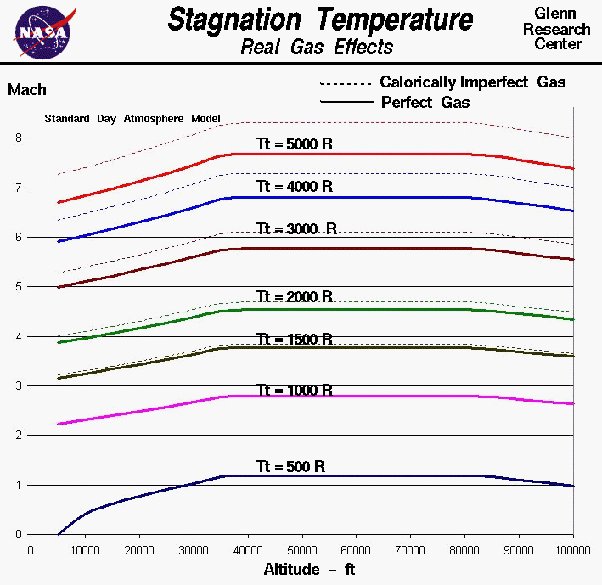

Here's a design envelope for a high speed turbojet. The grey lines show stagnation temperatures: At Mach 4 this is 900k, testing the metallurgical limits of many compressor blades.

Which is a shame, because we need the compressors to, well, compress air...

Which is a shame, because we need the compressors to, well, compress air...

For lowest fuel consumption, a generic turbojet needs a compressor pressure ratio (CPR) of 20 at Mach 2.4, but thermal heating limits mean that it can only hit a CPR of 9. The faster you go, the worse this is.

At Mach 4, achievable CPR is 1: No turbomachinery allowed!

At Mach 4, achievable CPR is 1: No turbomachinery allowed!

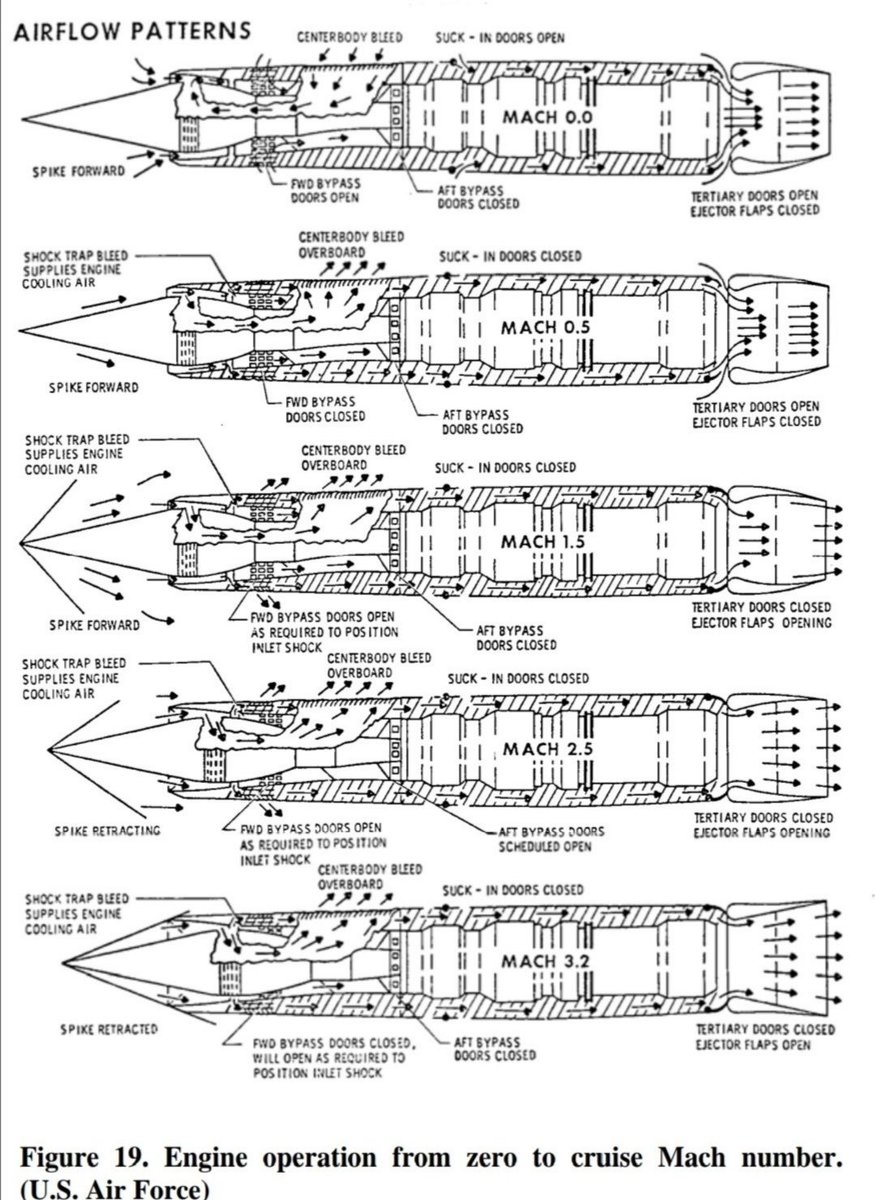

An afterburner can push the limits out a little, and a reheat bypass like the J58 engine in the SR71 helps, but still once you get a little over Mach 3 the afterburning turbojet is useless and we must turn to ramjets.

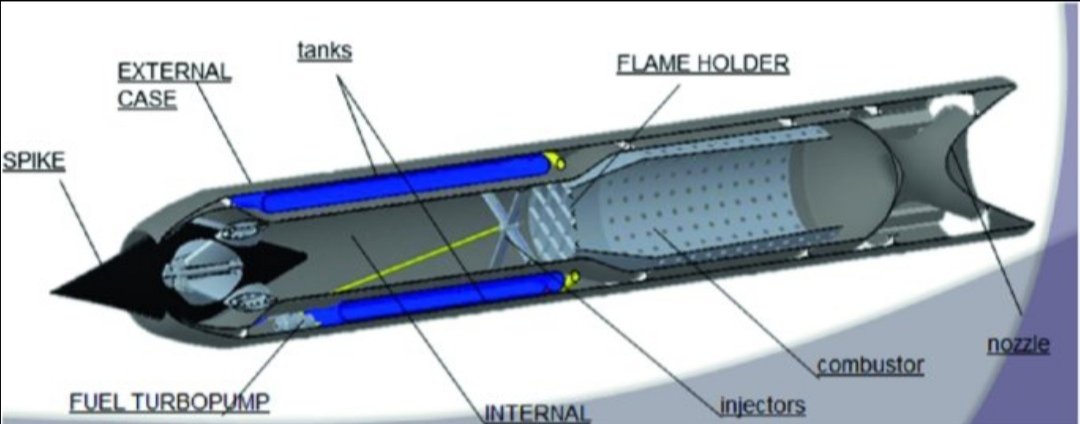

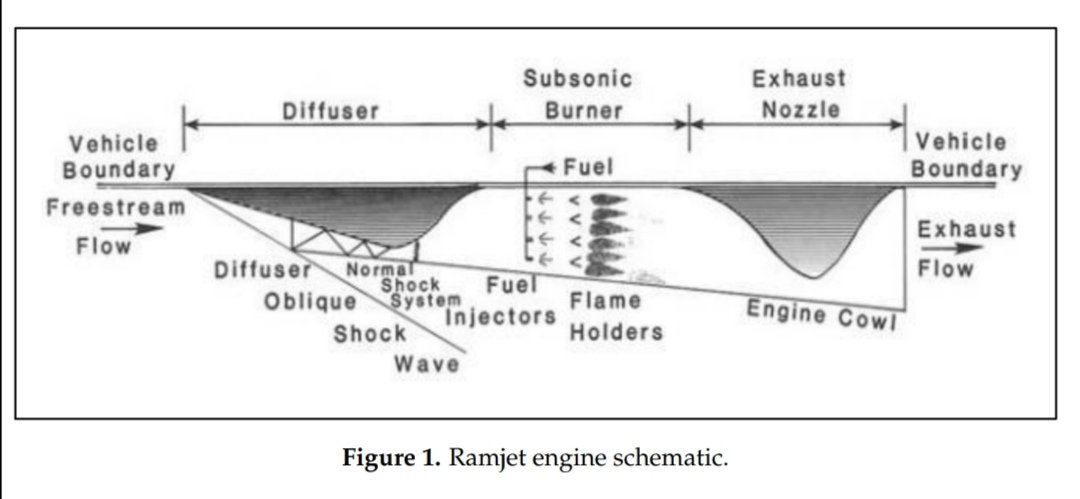

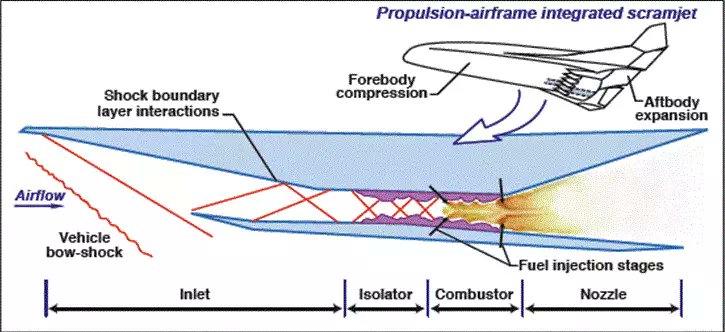

Ramjets have no turbomachinery! These simple little engines use the kinetic energy of the air itself, & carefully engineered shockwave generation, to compress and slow it to subsonic for combustion. A ramjet will get you to Mach 5 or 6, but below Mach 2-ish it won't work at all.

Get past Mach 5 or 6, though, and even a ramjet won't cut it: Too much energy & too much shock heating means that decelerating air to subsonic will impose unrecoverable losses and could slag your engine.

Why not use supersonic combustion, then? A Scramjet.

Why not use supersonic combustion, then? A Scramjet.

The scramjet uses a supersonic combustion chamber, with new problems like flame holding.

A normal engine uses a large recirculation zone to hold the flame. But in a scramjet the flow moves faster than the flame.

Like a rugby ball, the flame moves backwards. In a millisecond.

A normal engine uses a large recirculation zone to hold the flame. But in a scramjet the flow moves faster than the flame.

Like a rugby ball, the flame moves backwards. In a millisecond.

Scramjets also mean less ability to throttle & control your engine, meaning the aircraft may have to follow a constant dynamic pressure path: Climbing into thinner air as it accelerates.

And the high enthalpy of incoming air means that combustion is adding less comparatively.

And the high enthalpy of incoming air means that combustion is adding less comparatively.

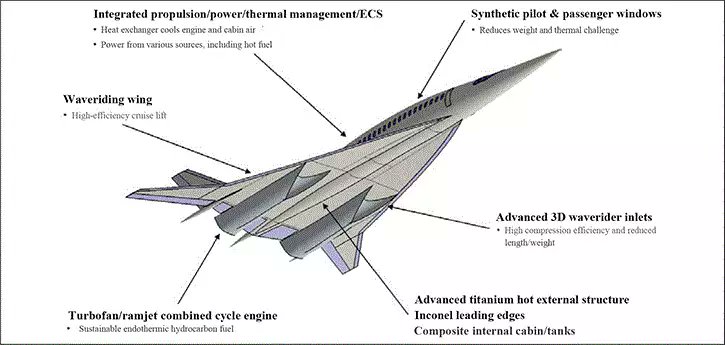

Fortunately, for an airliner travelling realistic distances Mach 5 is about as fast as it makes sense to go, so a combined cycle turbojet-ramjet would be sufficient.

Still, there remain issues. Heating & cooling, for example...

Still, there remain issues. Heating & cooling, for example...

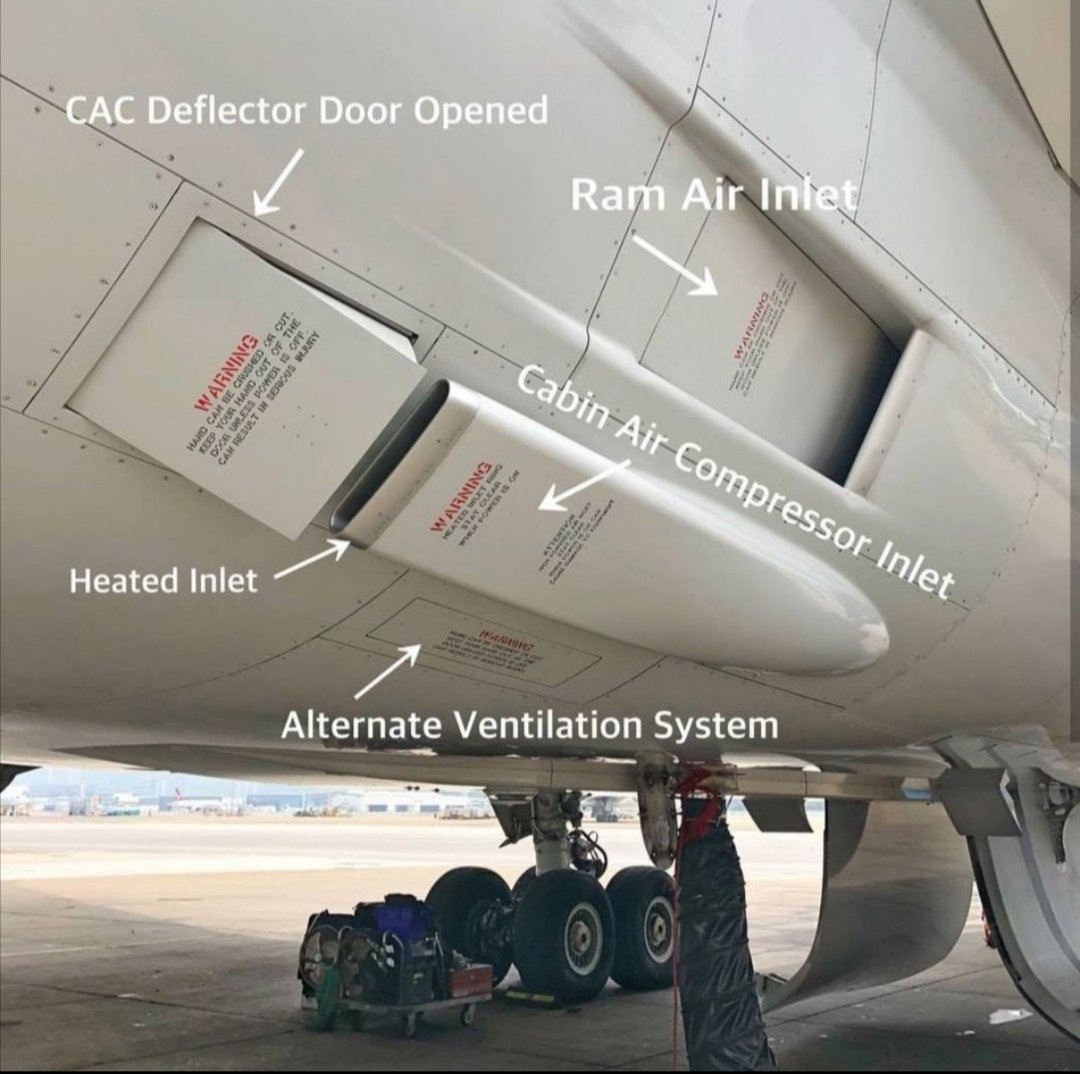

Cabin air needs heat exchangers even in normal airliners, where pressurising stratospheric air would otherwise bring it close to 90 Celsius.

But cooling is harder again when the stagnation temperature of incoming air would melt steel. Not impossible, but a challenge.

But cooling is harder again when the stagnation temperature of incoming air would melt steel. Not impossible, but a challenge.

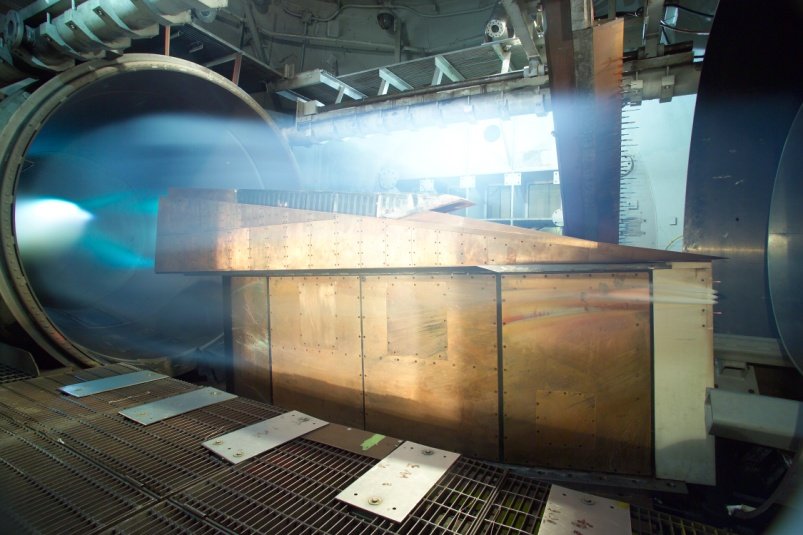

A heat exchanger ideally wants to maximise flow mixing near the boundary to maximise heat flux, but the same geometries that optimize for that also provoke strong shock generation in the coolant flow, dumping more heat energy.

The challenge is compounded by increased requirements for cooling for long cruises at high speeds: The engine needs high pressure coolant air. Even the fuel may need cooling.

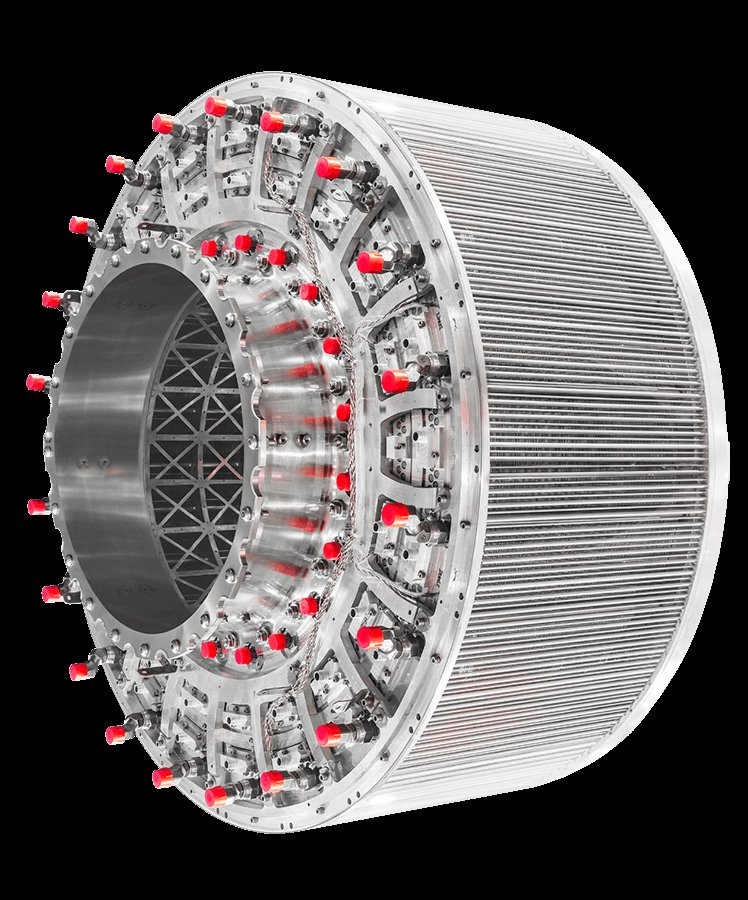

Little wonder that one of Reaction Engines' biggest accomplishments was a super fast heat exchanger.

Little wonder that one of Reaction Engines' biggest accomplishments was a super fast heat exchanger.

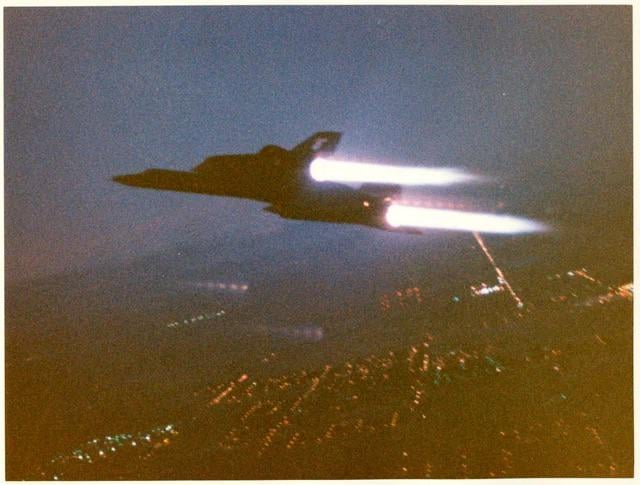

In fact, the challenge is so great that an alternative approach might be needed: The SR71, for example, used it's JP7 fuel, delivered cold, as a heat exchanging fluid to cool the cockpit & critical systems.

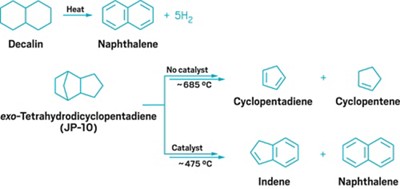

But taking that even further, why not endothermic fuels..?

But taking that even further, why not endothermic fuels..?

Dehydrogenation or cracking reactions can convert complex hydrocarbons into simpler ones in an endothermic reaction that absorbs heat. With the right fuel & catalyst mix, this could cool a hypersonic aircraft, but currently only in the lab and with coking deposits.

Or, if you're planning to power your hypersonic airliner with fast-burning hydrogen, just use the cryogenic hydrogen to cool the aircraft as it vapourises and travels to the engine. The extreme low temperature of stored liquid hydrogen helps in this case, at the cost of volume.

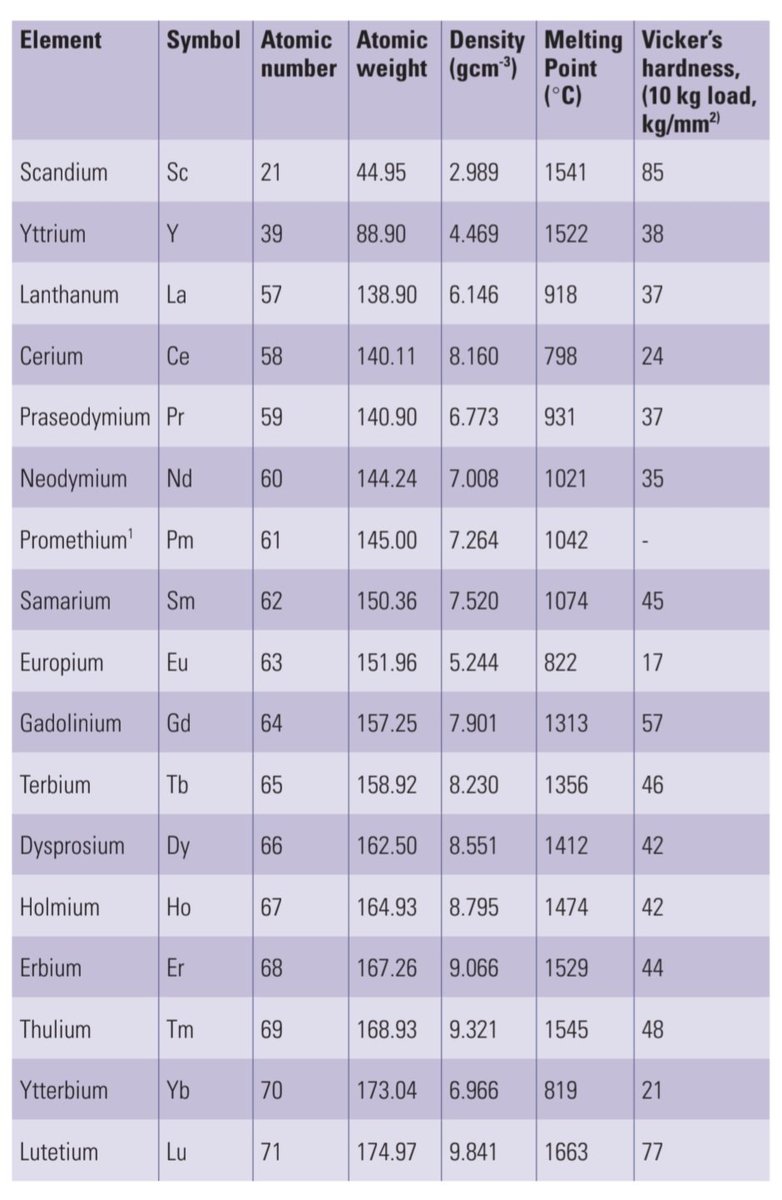

Materials.

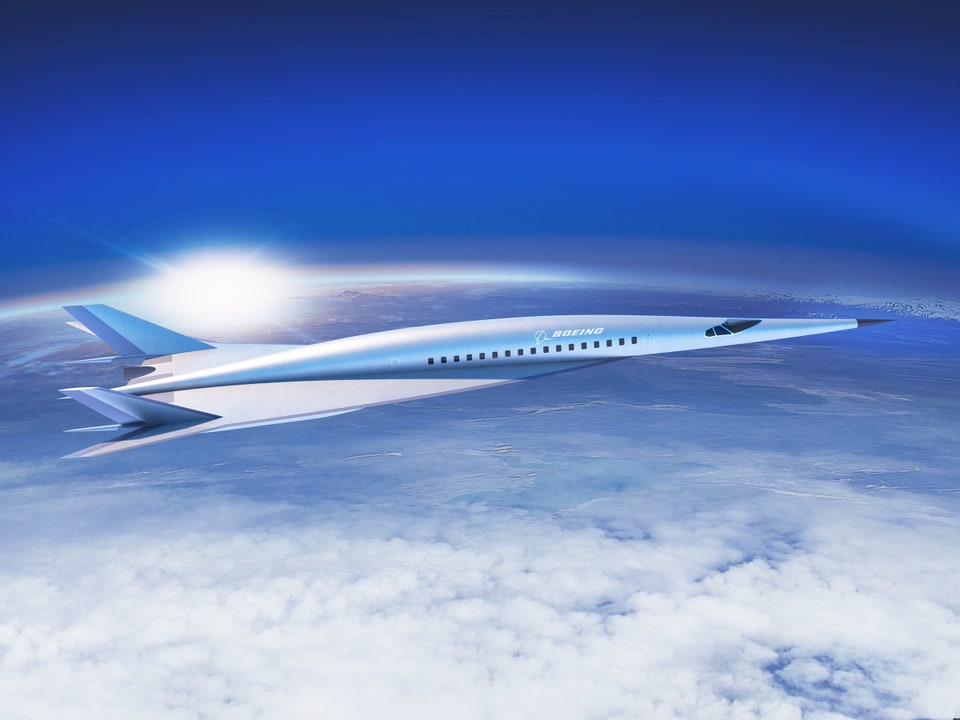

High temperatures on leading edges & nozzles demand the right materials. Titanium alloys will get you to the lower edge of the hypersonic realm, but thereafter nickels (too heavy) and high temperature carbon & ceramic matrix composites are likely contenders.

High temperatures on leading edges & nozzles demand the right materials. Titanium alloys will get you to the lower edge of the hypersonic realm, but thereafter nickels (too heavy) and high temperature carbon & ceramic matrix composites are likely contenders.

Human factors.

Limited cockpit visibility in most hypersonic designs will force virtual windows for pilots. Likewise virtual windows for passengers.

Safety margins for depressurization will change for extreme altitudes.

Limited cockpit visibility in most hypersonic designs will force virtual windows for pilots. Likewise virtual windows for passengers.

Safety margins for depressurization will change for extreme altitudes.

Why?

The human spirit says: Why not? Computational simulation & material science are opening the door to hypersonics now, just a crack, along with several successful drone tests.

What do mere apes yearn for?

To fly faster than angels, and pass through the nave of heaven...

The human spirit says: Why not? Computational simulation & material science are opening the door to hypersonics now, just a crack, along with several successful drone tests.

What do mere apes yearn for?

To fly faster than angels, and pass through the nave of heaven...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh