This academic year marks a decade of teaching military history in higher education for me.

I'd like to reflect upon the demographic that keeps me employed: my students who are "into" military history. I'm going to try to limit myself to observations rather than judgement. 🧵1/25

I'd like to reflect upon the demographic that keeps me employed: my students who are "into" military history. I'm going to try to limit myself to observations rather than judgement. 🧵1/25

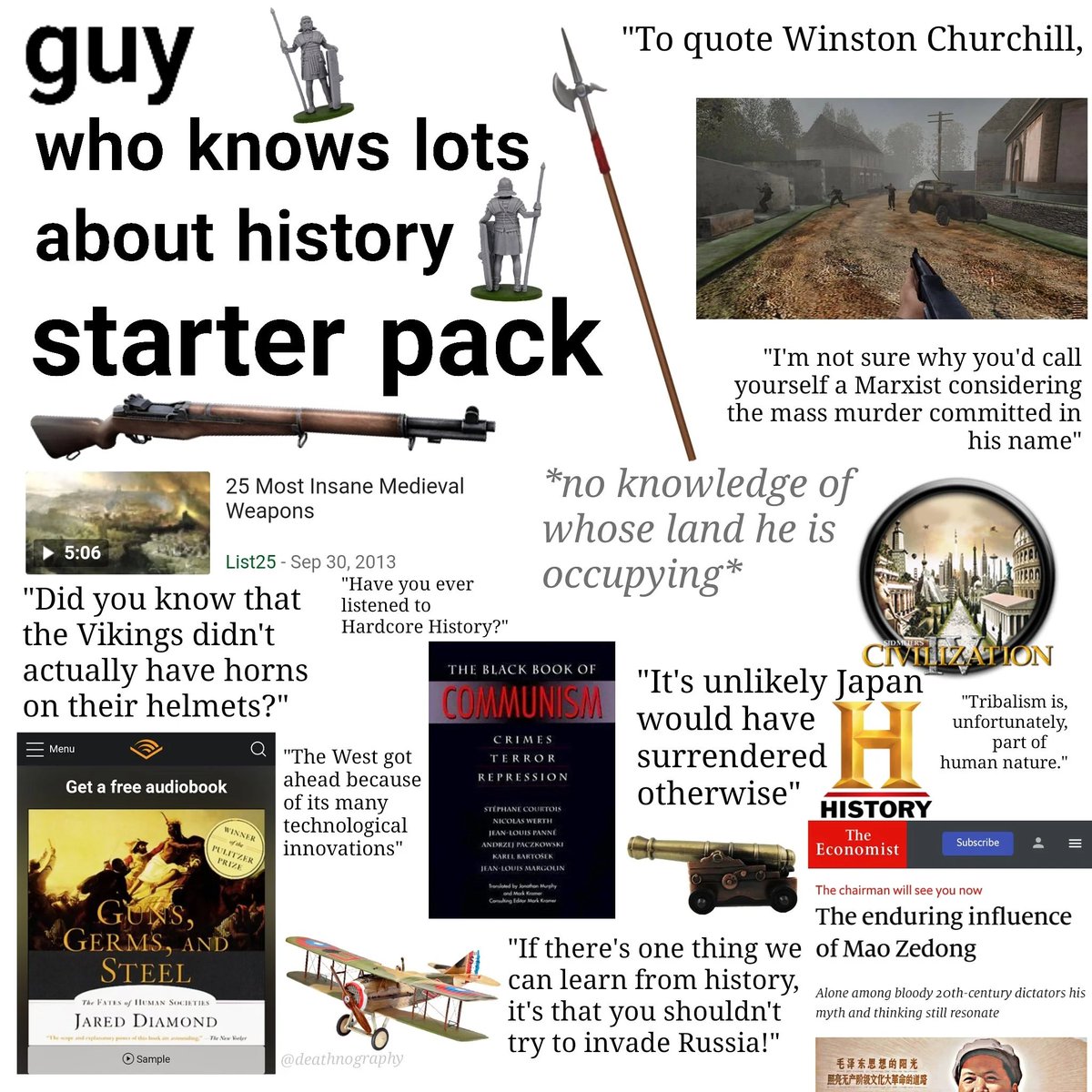

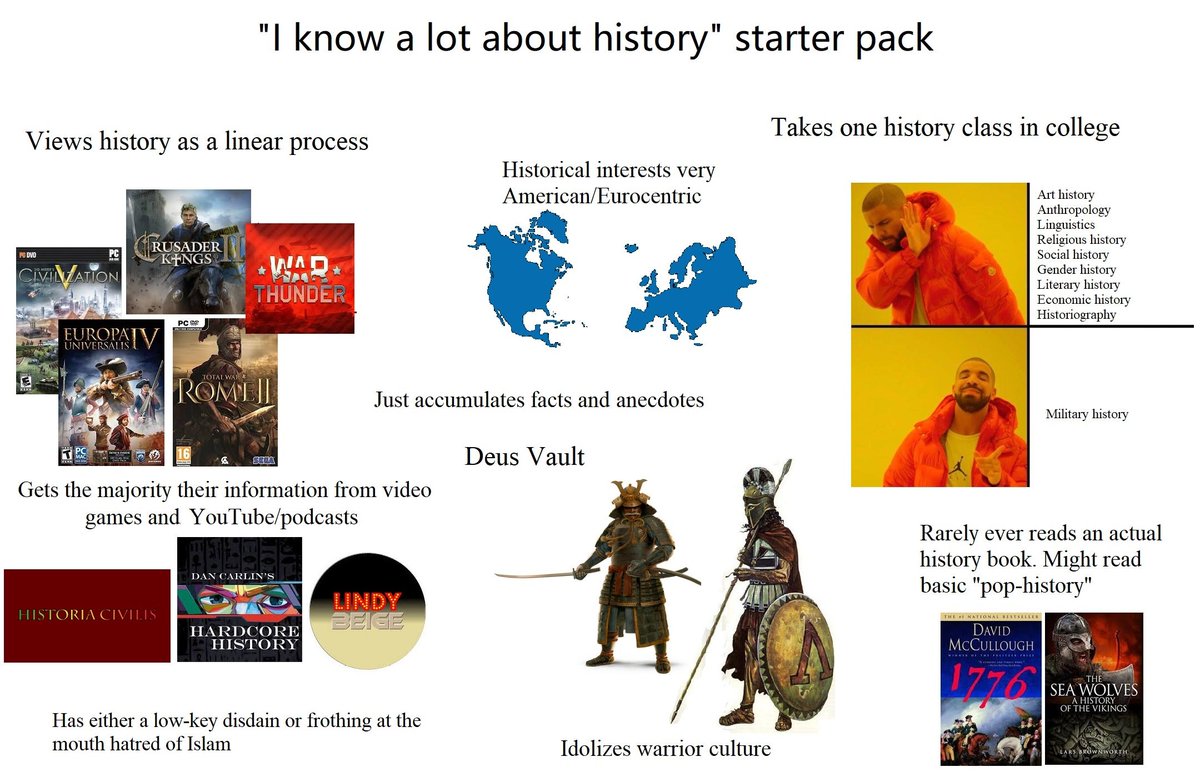

These young people are frequently derided with memes about "starter packs" or paradox games. Some of my fellow graduate instructors at WVU called them "military history bros." Although a number of them were conservative white men, I've taught "milhist bros" of all stripes: 2/25

women, people of color, liberals in both the modern and classical sense. An interest in military history isn't something you can just predict by looking at someone. These students did bother faculty members at times: 3/25

When I expressed my desire to be a military historian to my undergraduate advisor, he replied, "Alex, I lost interest in most of that after age 10." So, the "milhist bros" never bothered me much, I used to be one. 4/25

Though, as a homeschooler, I like to think I was a bit quieter than most. What does bother me is students who fail to progress in their interest. I think there a few levels of interest/knowledge in military history among non-professionals, charting that is the point here. 5/25

Here are the levels, as I understand them:

Paradigm Invocation

Paradigm Rejection

Social/Cultural Contextualization

Measured Appreciation 6/25

Paradigm Invocation

Paradigm Rejection

Social/Cultural Contextualization

Measured Appreciation 6/25

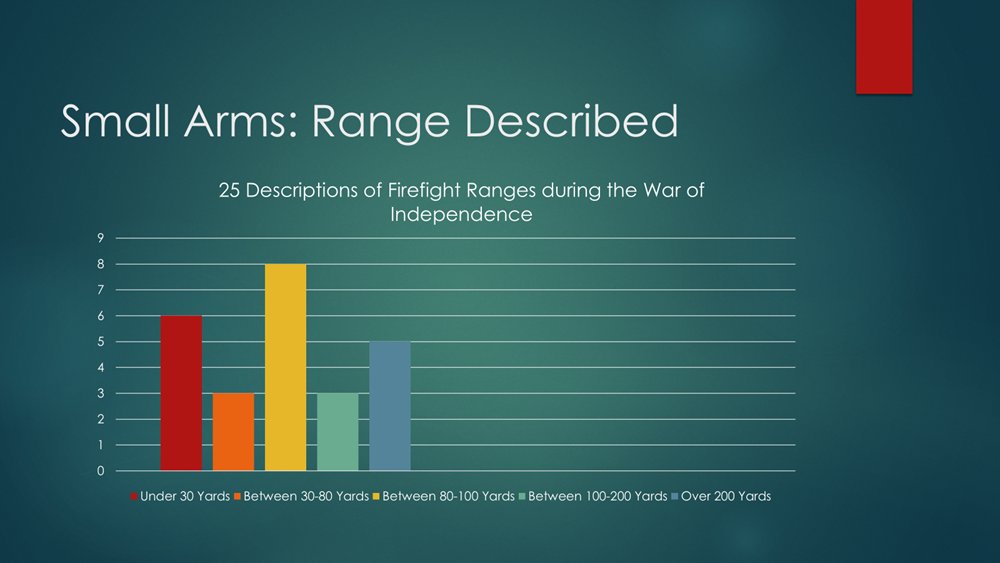

Paradigm Invocation is the most common level of engagement with military history I see in both the classroom, and military historical public. The enthusiast invokes a personal/technological aspect of a "paradigm army" in the way a pre-modern individual might a charm. 7/25

"The main gun of the Tiger I..."

"The leather cannons of Gustavus Adolphus..."

"The longrifle of the America Frontiersmen..."

"Patton's Third Army..."

"Together, Lee and Jackson..."

"The Oblique Attack of Frederick the Great..."

"The Baker Rifle of the Lights..."

and so on. 8/25

"The leather cannons of Gustavus Adolphus..."

"The longrifle of the America Frontiersmen..."

"Patton's Third Army..."

"Together, Lee and Jackson..."

"The Oblique Attack of Frederick the Great..."

"The Baker Rifle of the Lights..."

and so on. 8/25

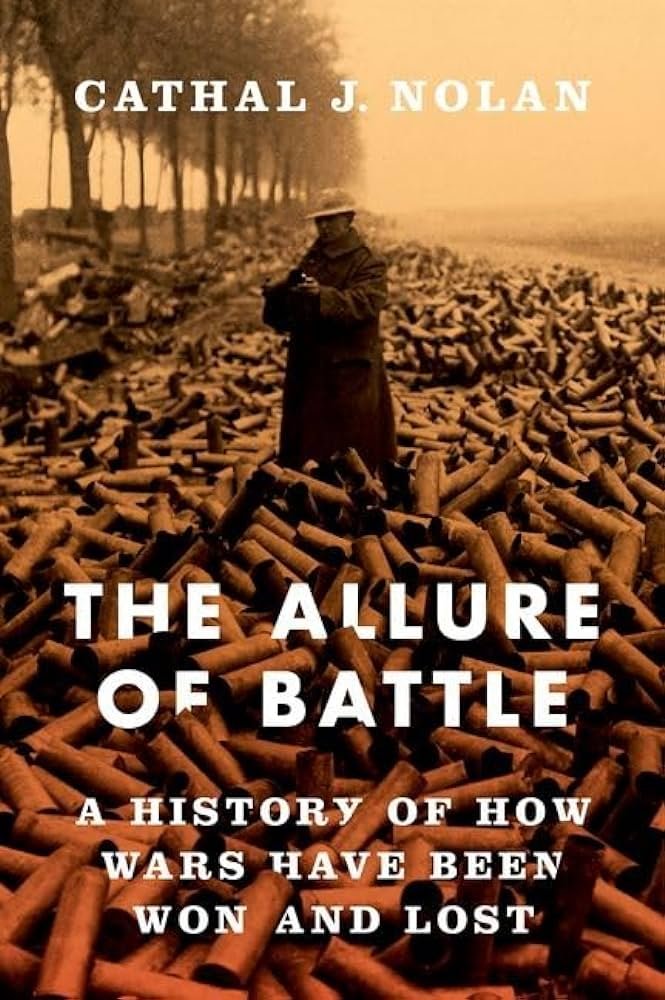

In my mind, this is to some extent what Cathal Nolan was fighting against in "The Allure of Battle,": the notion that we can quickly sum up periods of military history via their "stats" and the performance of those stats at "decisive battles." 9/25

When asked to say more on a particular period, the Paradigm Invoker often can't. When the enthusiast at your wargame table has explained how the Swedish leather guns at Breitenfeld were superior they often fall flat when you ask: "Tell me why Tilly won Wimpfen and Lutter?" 10/25

This isn't a problem, especially if they are in your classroom! You have the chance now to push who is already enthusiastic to think a bit deeper! This is an opportunity rather than something to be annoyed at, at least in my book. 11/25

Now, next we have the Paradigm Rejector. In many ways, this is the same as the evangelical fundamentalist who becomes an antitheist: the same frameworks are still at work. Sometimes they will invoke the work of historians who contextualize paradigm armies. 12/25

"The Tiger Tanks were worthless, they didn't have parts..."

"The Spanish Tercios won Nördlingen, the Swedes weren't good."

"Robert E. Lee was actually a bad general."

"Franz Szabo reminds us Frederick "the Great" was a pathetic general." 13/25

"The Spanish Tercios won Nördlingen, the Swedes weren't good."

"Robert E. Lee was actually a bad general."

"Franz Szabo reminds us Frederick "the Great" was a pathetic general." 13/25

Often, the Paradigm Rejectors, who are, on average, a bit more well read than the Paradigm Invokers, are the most difficult to shift in their opinions, and think they have it "figured out." Trying to play devil's advocate for the paradigm army is rarely a good solution: 14/25

This group will simply label you as a midwit who believes "the old lie" and shut down. Instead, my recommendation is to push these folks to read beyond the battles towards the logistics, operations, and perhaps most importantly, social and cultural context. 15/25

Having these students read beyond the battlefield is rewarding: the realization that the Canton System was more important to Frederick's success than iron ramrods *is * something that the paradigm rejectors are mentally receptive to, at least in my experience. 16/25

These are the students who are ready to tackle social and cultural military history, and engage with primary sources in a meaty way, moving beyond battle snippets to the overall experience of war. Time and reading will give turn Paradigm Rejectors into Contextualizers. 17/25

This group is finally equipped to make value judgements about what made the paradigm armies unique: it wasn't always just those tactical deployments or technological marvels: it was the that paired with their social/cultural context. 18/25

This group is a delight: they are focused on things like the experience of the average rather than the elite. Asking "What was normal?" prepares them to finally understand what was unique about each of the armies of their period, and gain appreciation for it. 19/25

This group is focused on source criticism, epistemological questions, transnational comparisons, in addition to "war and society" and cultural history. Obviously, I've known many professionals in this group, but a surprising number of wargames and reenactors as well. 20/25

Only by placing the paradigm army alongside its real opponents, rather than strawmen, can they finally begin to appreciate the complexity of the period. What motivated, clothed, paid, fed, and armed the men? How were they moved? 21/25

Bringing it all together allows for an measured appreciation of the achievements of the paradigm army, in addition to its flaws, moving beyond the surface level. Some students can make this jump in weeks. Others never do. It took me multiple semesters. 22/25

If you see yourself in this list, don't feel judgement or criticism. Instead, read more, and enjoy the process, moving from memes to monographs, so to speak. Our society is better served by having people understand war in a substantial and serious way. 23/25

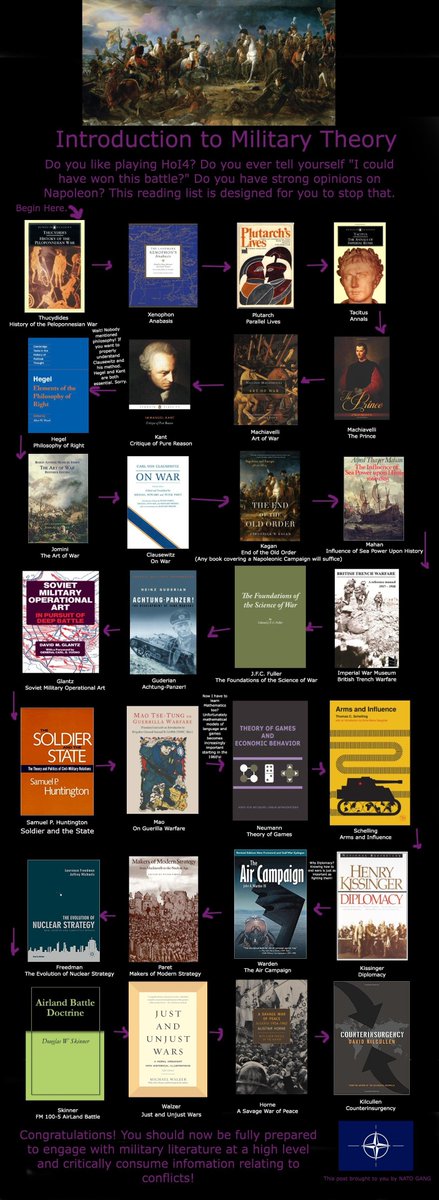

James provides this helpful crash-course below. People who have spent months and years studying war in a serious way are rarely jumping up and down for conflicts to begin. 24/25

I hope this was helpful in terms of thinking about how people engage with the past, and encouraging a deeper engagement in thinking about military history and conflict.

And yes, Paradigm Rejectors, I know the Swedes didn't actually use leather guns at Breitenfeld. 25/25

And yes, Paradigm Rejectors, I know the Swedes didn't actually use leather guns at Breitenfeld. 25/25

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh