There's more to the world of art than Leonardo da Vinci and Pablo Picasso.

So here are 11 brilliant, beautiful, & bizarre painters you've (probably) never heard of:

So here are 11 brilliant, beautiful, & bizarre painters you've (probably) never heard of:

1. Hans Baluschek (1870-1935)

Baluschek was fascinated by industrialisation: the rise of factories, chimney stacks, machinery, and trains, along with the lives of the people in these rapidly growing, smog-filled metroplises.

As in City of Workers, from 1920:

Baluschek was fascinated by industrialisation: the rise of factories, chimney stacks, machinery, and trains, along with the lives of the people in these rapidly growing, smog-filled metroplises.

As in City of Workers, from 1920:

Baluschek's paintings feel like a world of their own — a sort of endless dream (or nightmare?) of a vast, industrial city, always at night, always filled with stories and hidden moments, seen from a thousand different perspectives.

Cinematic and compelling.

Cinematic and compelling.

2. Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892)

The last great master of traditional Japanese ukiyo-e prints before modernisation swept them away.

Yoshitoshi was a prolific designer of ukiyo-e who pushed the genre further than anybody had done in its three centuries of history.

The last great master of traditional Japanese ukiyo-e prints before modernisation swept them away.

Yoshitoshi was a prolific designer of ukiyo-e who pushed the genre further than anybody had done in its three centuries of history.

Whereas the likes of Hokusai and Hiroshige are famous for their harmony and relative simplicity, Yoshitoshi embraced chaos and disorder.

His series range from comical to ghastly to gruesome to epic, and embrace everything from samurai legends to daily life.

His series range from comical to ghastly to gruesome to epic, and embrace everything from samurai legends to daily life.

3. Marie Spartali Stillman (1844-1927)

One of the great Pre-Raphaelite artists — this was a British movement which tried to return art to its Medieval roots of colour and detail, before the Renaissance had stripped that away.

Stillman's paintings are almost like tapestries.

One of the great Pre-Raphaelite artists — this was a British movement which tried to return art to its Medieval roots of colour and detail, before the Renaissance had stripped that away.

Stillman's paintings are almost like tapestries.

She was a master of colour and texture, somehow giving her paintings a sort of shimmering quality.

And notice, in her painting of the great Italian poet Petrarch meeting his muse, Laura, her careful attention both to their clothes and to the details of Gothic architecture.

And notice, in her painting of the great Italian poet Petrarch meeting his muse, Laura, her careful attention both to their clothes and to the details of Gothic architecture.

4. Thomas Chambers (1808-1869)

A rather unusual painter whose stylised scenes of ships were genuinely decades ahead of their time.

He was born in the old English port town of Whitby but moved to and became a citizen of the US.

Chambers was a modernist before modernism existed.

A rather unusual painter whose stylised scenes of ships were genuinely decades ahead of their time.

He was born in the old English port town of Whitby but moved to and became a citizen of the US.

Chambers was a modernist before modernism existed.

Chambers was not recognised for nearly a century after his life, partly because his paintings were mostly unsigned and partly because of how unusual he was.

His style is similar to Grant Wood, of American Gothic fame, with those smooth surfaces and cartoon-like forms.

His style is similar to Grant Wood, of American Gothic fame, with those smooth surfaces and cartoon-like forms.

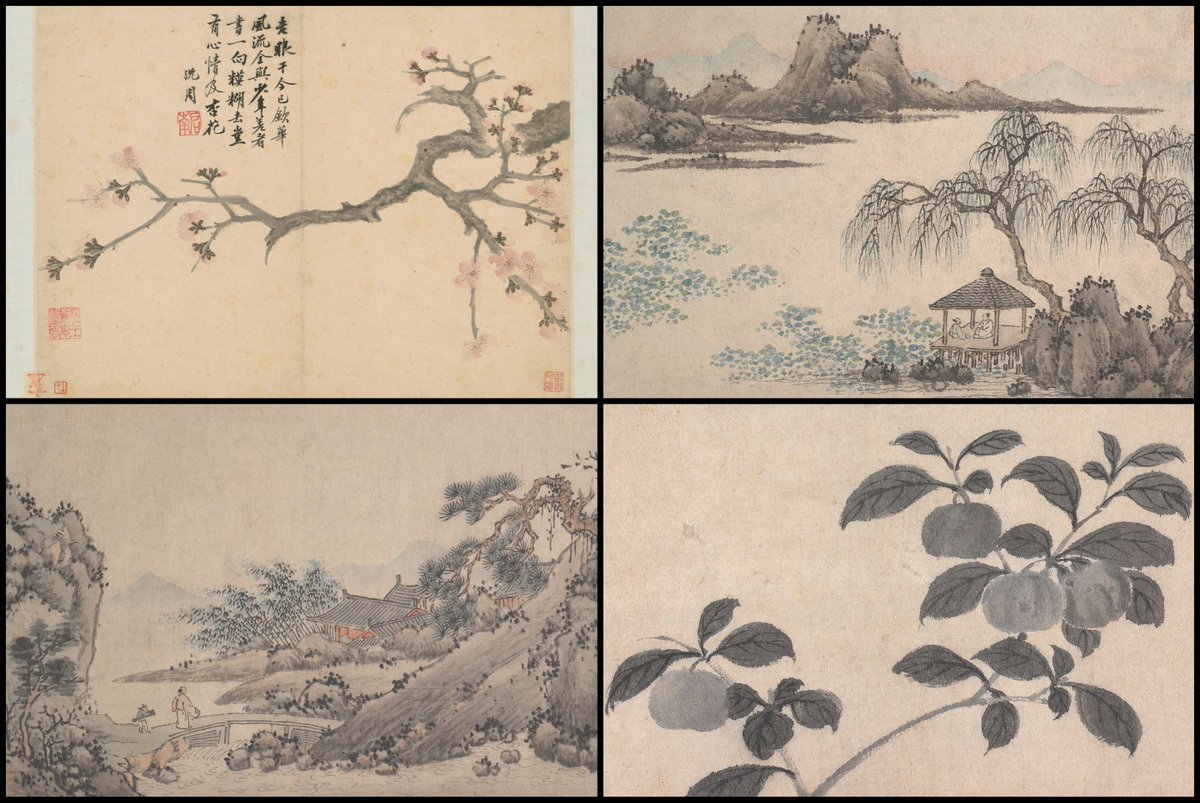

5. Shen Zhou (1427-1509)

Shen Zhou was one of the later artists in the long and time-honoured tradition of landscape painting at the Chinese courts.

This was about capturing the essence of a landscape rather than its mere outward appearance.

Poetry as painting.

Shen Zhou was one of the later artists in the long and time-honoured tradition of landscape painting at the Chinese courts.

This was about capturing the essence of a landscape rather than its mere outward appearance.

Poetry as painting.

Many of his paintings are delightfully minimalist, giving us either details — fruit, leaves, branches, birds — or entire landscapes with the fewest possible brushstrokes.

Serene, peaceful, soothing.

Serene, peaceful, soothing.

6. Jacob Isaaczoon van Swaneburg (1571-1638)

He was, perhaps, a man after his time — his art harked back to the wild imaginings of Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Brueghel the Elder.

But, if you like those painters, you'll love Isaaczoon van Swaneburg.

He was, perhaps, a man after his time — his art harked back to the wild imaginings of Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Brueghel the Elder.

But, if you like those painters, you'll love Isaaczoon van Swaneburg.

He embraced that same madness which teeters on the brink between genuinely horrifying and almost comically surreal.

7. Charles Meryon (1821-1868)

A fascinating man with a complex life that ended in tragedy.

Meryon always wanted to be a painter but because he suffered from severe colourblindness he could not do it.

So he turned to etching and became a master of that form instead.

A fascinating man with a complex life that ended in tragedy.

Meryon always wanted to be a painter but because he suffered from severe colourblindness he could not do it.

So he turned to etching and became a master of that form instead.

Meryon produced dozens of gorgeously atmospheric, brooding, Gothic vignettes of Paris.

He had a keen eye for architecture and for the details of urban life, from clusters of weeds growing on buildings to the dingy corners and unscrupulous characters of the city.

He had a keen eye for architecture and for the details of urban life, from clusters of weeds growing on buildings to the dingy corners and unscrupulous characters of the city.

8. Giovanni di Paolo (1403-1482)

Di Paolo was part of the "Sienese School" — this was a group of artists who held on to the old, Medieval ways of painting rather than following the new methods of the Renaissance.

Old-fashioned by design — and delightfully archaic.

Di Paolo was part of the "Sienese School" — this was a group of artists who held on to the old, Medieval ways of painting rather than following the new methods of the Renaissance.

Old-fashioned by design — and delightfully archaic.

If you like this sort of highly stylised, Early Renaissance art then you'll love Giovanni di Paolo.

He also made a series of illustrations for Dante's Divine Comedy which are worth looking at if only to see how Medieval people visualised that famous journey.

He also made a series of illustrations for Dante's Divine Comedy which are worth looking at if only to see how Medieval people visualised that famous journey.

9. Sofonisba Anguissola (1532-1625)

One of the first female painters of the Italian Renaissance, mentioned in Giorgio Vasari's famous Lives of the Artists and apparently admired by Michelangelo.

She had a distinctive, almost pearlescent style, and a fabulous sense of humour.

One of the first female painters of the Italian Renaissance, mentioned in Giorgio Vasari's famous Lives of the Artists and apparently admired by Michelangelo.

She had a distinctive, almost pearlescent style, and a fabulous sense of humour.

For her self-portrait Anguissola painted her teacher, Bernadino Campi, while he was painting a portrait of her, thus capturing both of them of them at once.

No doubt some subtle jokes or meta-commentary going on here.

No doubt some subtle jokes or meta-commentary going on here.

10. Samuel Prout (1783-1852)

One of the greatest watercolourists who ever lived, a self-taught artist from Plymouth in southern England who travelled around capturing ordinary street scenes whether in Britain or in Europe.

Like Meryon he was a master of architectural details.

One of the greatest watercolourists who ever lived, a self-taught artist from Plymouth in southern England who travelled around capturing ordinary street scenes whether in Britain or in Europe.

Like Meryon he was a master of architectural details.

But that's not all; Prout was also fond of ships and of the sea, and he painted these with that same ability to conjure a sense of grand scale and minute detail at once.

On the whole his art is incredibly peaceful.

On the whole his art is incredibly peaceful.

11. Jacek Malczewski (1854-1929)

Jan Matejko is surely Poland's greatest painter — but Jan Malczewski, a master of Symbolism, isn't far behind.

His style is hard to explain and, true to the Symbolist creed, his meanings are even harder to decipher.

Jan Matejko is surely Poland's greatest painter — but Jan Malczewski, a master of Symbolism, isn't far behind.

His style is hard to explain and, true to the Symbolist creed, his meanings are even harder to decipher.

And so Malczewski's paintings are worth investigation — attempting to unravel their meaning, even when he is painting a scene from the Bible or Mythology, is always a journey for the viewer.

Besides, his use of colours and unusual angles create visual riddles of their own.

Besides, his use of colours and unusual angles create visual riddles of their own.

So these were just 11 of thousands of wonderful artists from around the world and across the centuries.

Leonardo and Picasso may be the most famous — but you don't have to like them.

The world of art rewards exploration, and the internet has made that simpler than ever...

Leonardo and Picasso may be the most famous — but you don't have to like them.

The world of art rewards exploration, and the internet has made that simpler than ever...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh