Yankee-Irish conflict and the Boston Draft Riot of 1863: Refugees from the Great Famine caused Boston’s Irish population to explode - rising from a mere handful, to over a third of the city’s population.

One Yankee complained that Boston had become the “Dublin of America." 🧵/26

One Yankee complained that Boston had become the “Dublin of America." 🧵/26

The city simply could not cope with the deluge. Poverty stricken and unskilled, the new arrivals were packed into crowded tenements. Disease and unsanitary conditions took a terrible toll. During a cholera epidemic, the life-expectancy of Irish males fell to fourteen years. 2/26

Not surprisingly, this tidal-wave of poverty-stricken Catholic immigrants did not receive a warm welcome from the Puritan-descended Yankees of Boston. The “shattering of Boston’s ethnic homogeneity” created an intense anti-Irish, anti-Catholic backlash. 3/26

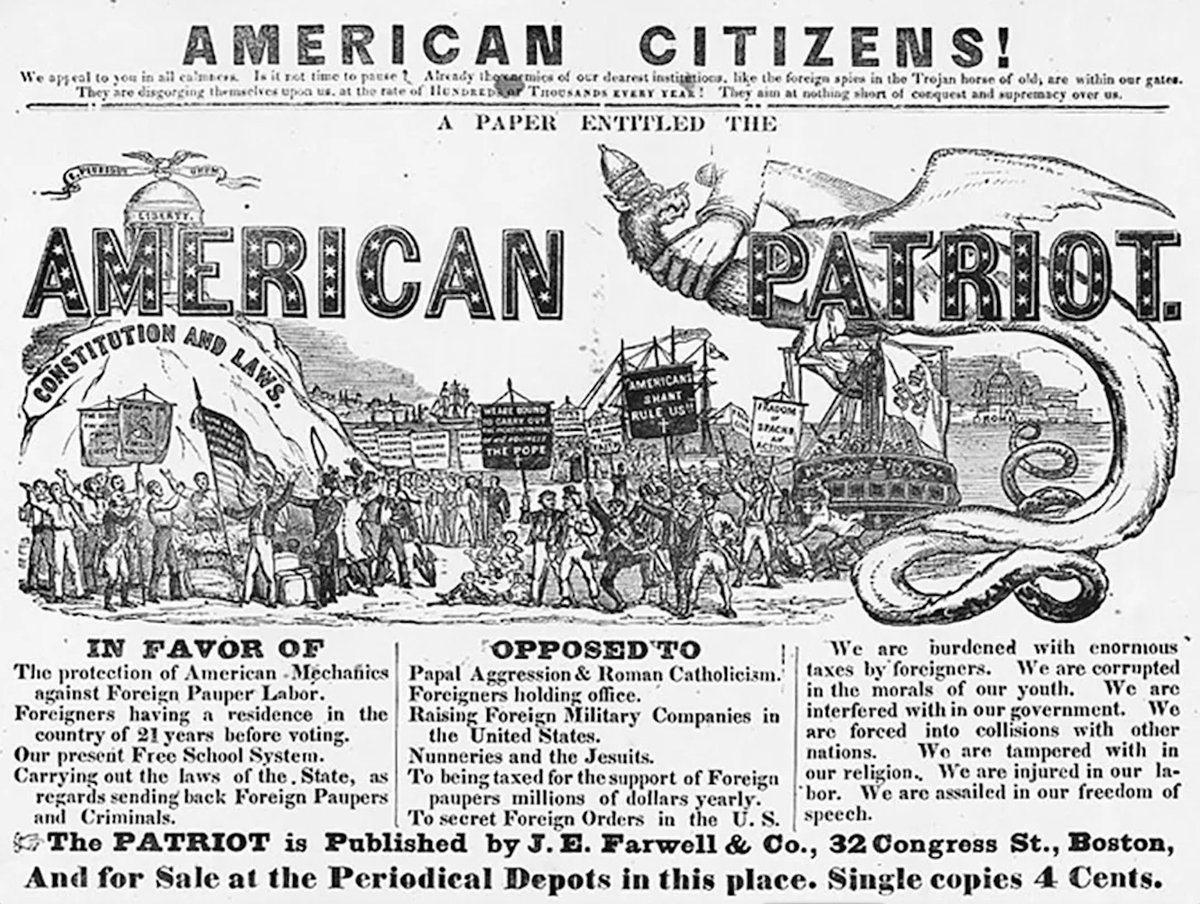

Politically, the backlash took form in an anti-immigrant, populist movement - the American Party – better known as the “Know-Nothings.” In 1854, the Nothings won “the greatest triumph for a single party in the tumultuous history of Massachusetts politics.” 4/26

In addition to opposing Irish immigration, there were strong “progressive,” “reform” elements to Yankee politics – They favored prohibition, they were early proponents of school desegregation. They supported the native working class, and were strongly opposed to slavery. 5/26

The Yankee progressive reformers viewed the Catholic immigrants as reactionaries. And some Catholics proudly pleaded guilty to the charge – mocking the Yankees as “infidels and heretics” – “red republicans,” who favored women’s rights and socialism. 6/26

In the 1850s immigrants drifted toward the Democratic Party. So even before the Civil War, the terms were taking-shape for national political conflict that would endure for decades – Yankee Republicans opposed by Southerners and Irish Catholics Democrats. 7/26

By the late 1850s, anti-slavery had become the overriding cause for the Yankees. The Irish were hostile toward the abolitionist movement – they saw it as a danger to the interests of White workers, and as a revolutionary threat to the Constitution. 8/26

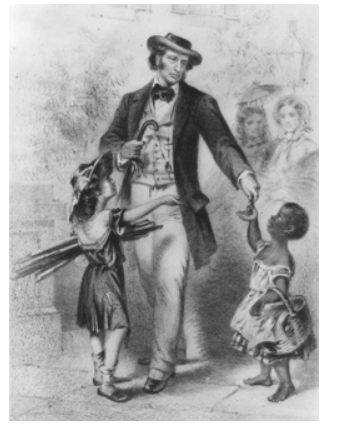

And the Irish seethed at what they perceived as abolitionist hypocrisy – the Yankees seemed to obsess over conditions of Blacks in the South, while ignoring the suffering of poor Whites in Boston. 9/26

The Irish frustration was an echo of Dickens, who in “Bleak House” had coined the term "telescopic philanthropy" a few years earlier - describing liberals who obsessed over far-away charitable causes, while ignoring children starving on the streets of London. 10/26

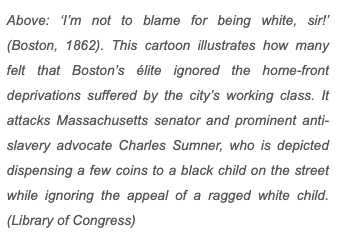

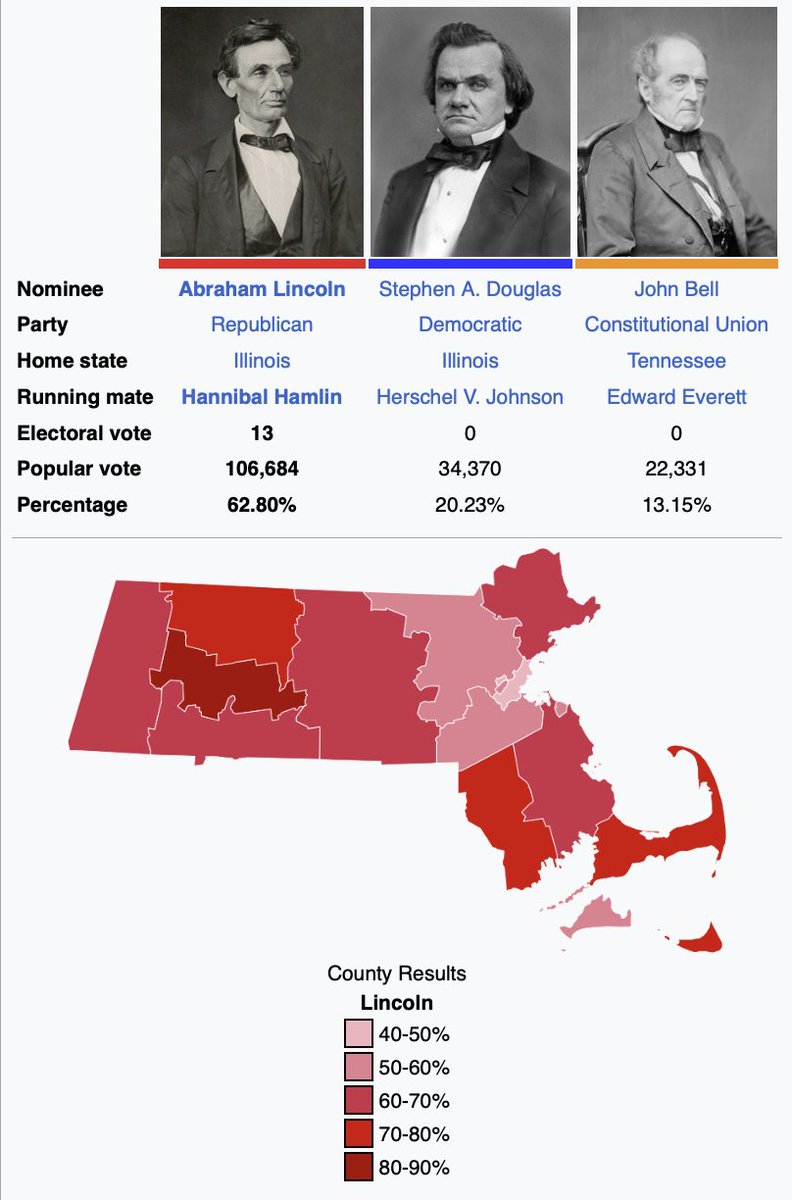

The Yankee-Irish spit was typified in the fateful election of 1860: Lincoln carried the state of Massachusetts by a wide margin. But Lincoln did poorly in the city of Boston, where the Irish wards strongly supported the Democrat Stephen Douglas. 11/26

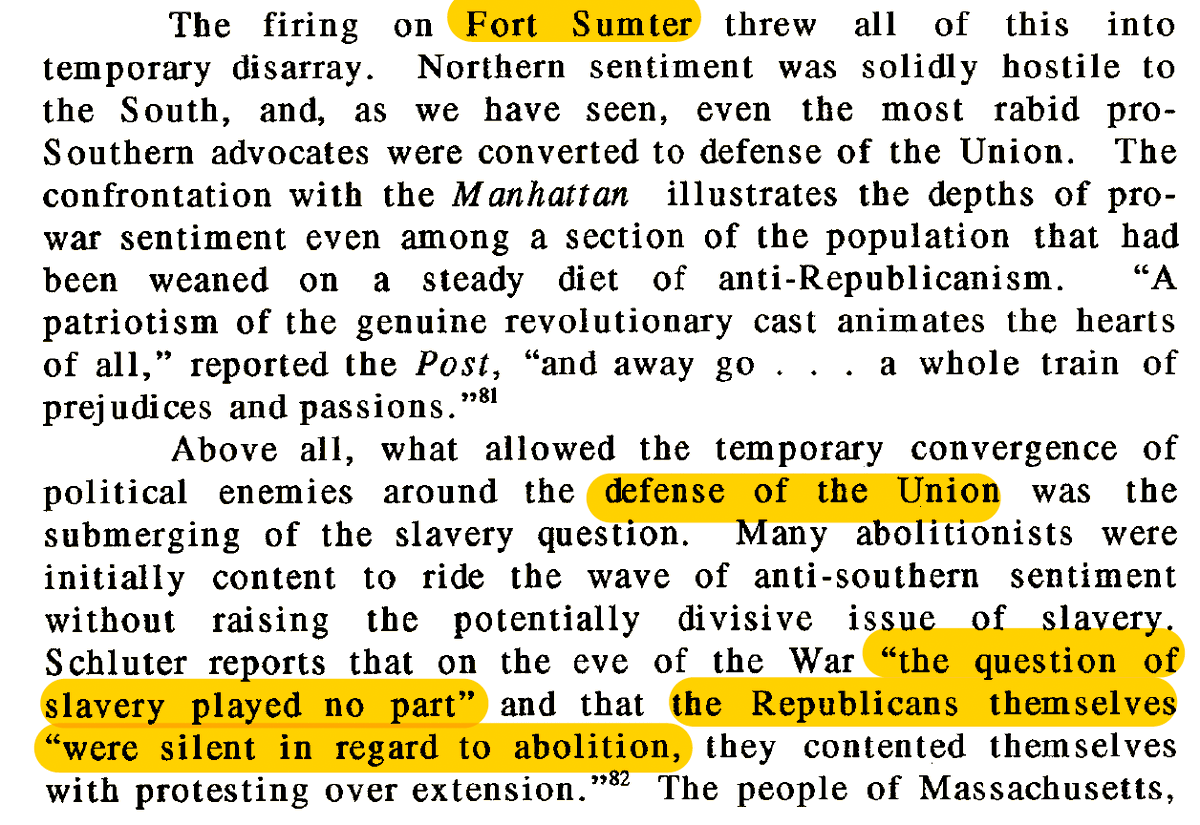

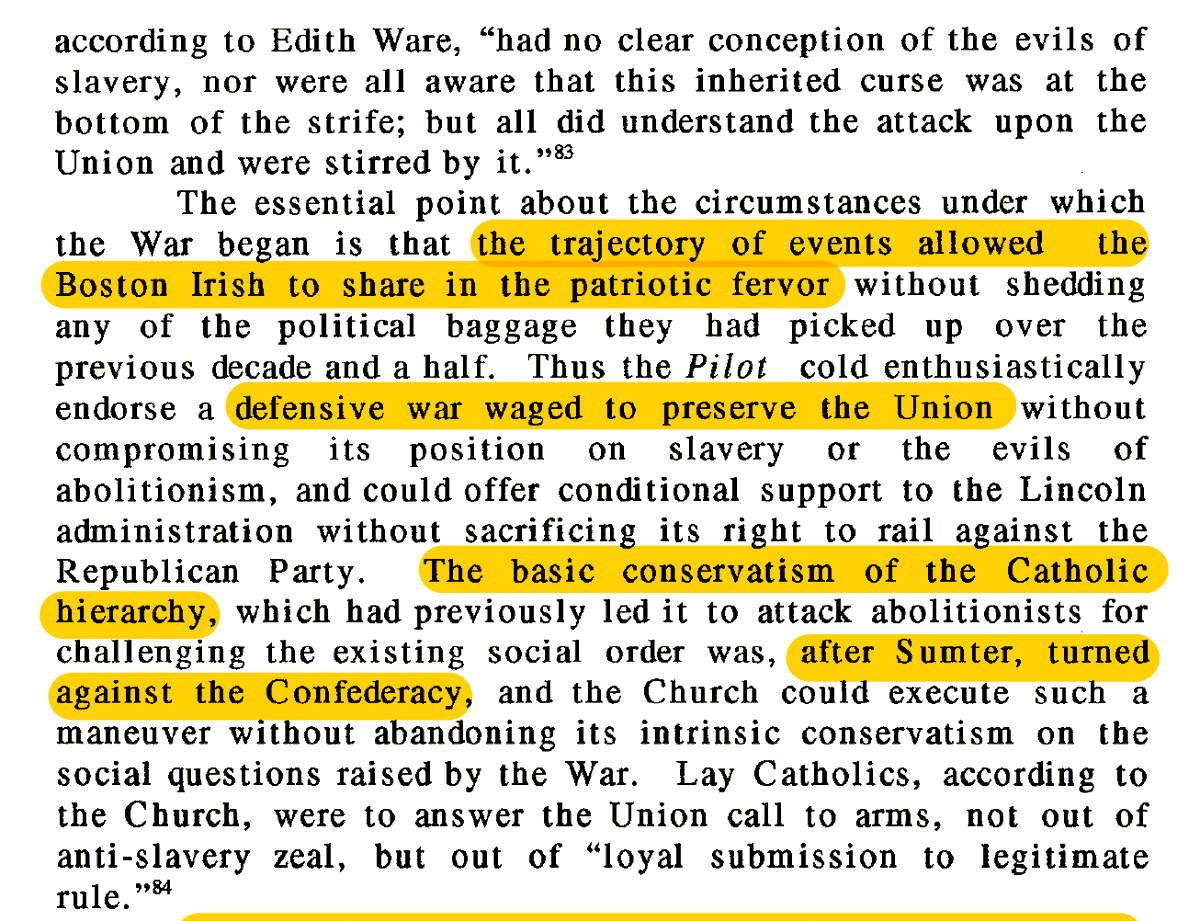

Despite their opposition to Lincoln and the abolitionists, the Irish were swept-up in the 1861 war fever that followed the attack on Fort Sumpter. The Irish came to view the conflict as a defensive war to save the Union, and they volunteered in great numbers. 12/26

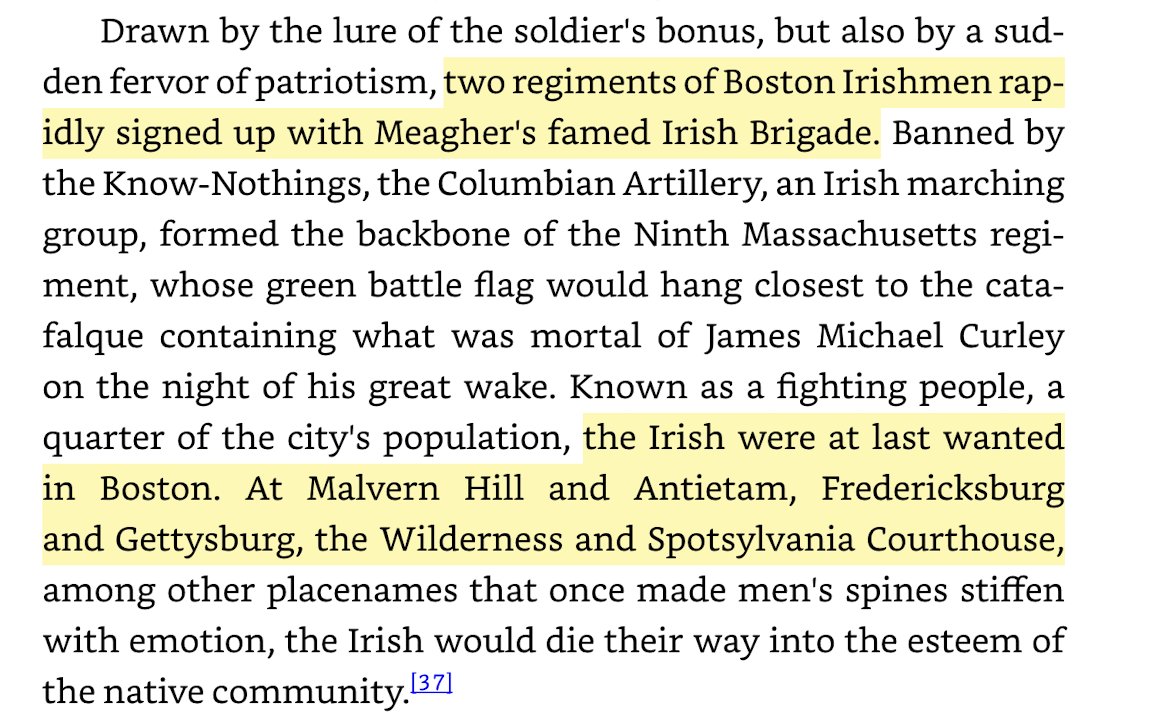

Boston’s Irish contributed regiments to the Union Army’s Irish Brigade – A highly regarded formation that fought with valor and distinction in several battles. But the brigade and the Boston Irish took horrendous casualties. 13/26

By 1863 Boston’s Irish were bitterly disillusioned with the war, Lincoln, and the Republicans. It was not merely the heavy casualties, but the perception that the war had been transformed from a struggle to save the union into a struggle for abolition. 14/26

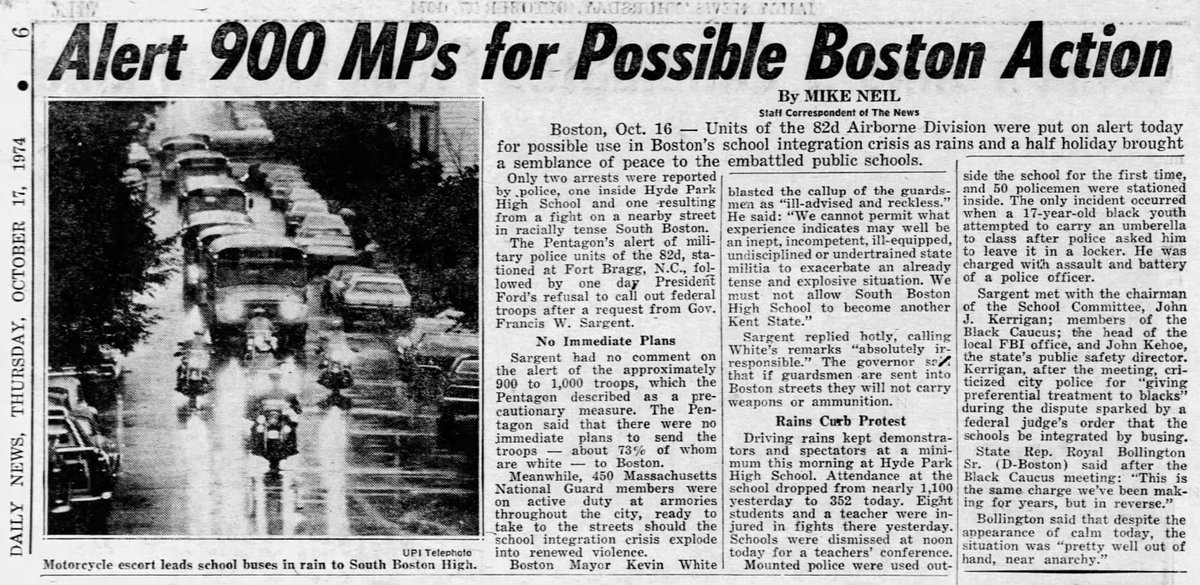

As with the much larger and bloodier New York City draft riot, the riot in Boston was triggered by the infamous 1863 conscription act, passed by a Republican-dominated Congress. War-critics blasted the act, and their attacks resonated with a disillusioned, war-weary public. 15/26

Those with the means could avoid military service by hiring a substitute, or by paying $300. This de-facto exemption for the wealthy lent credence to the charge that the conflict was a “rich man’s war, poor man’s fight.” Resistance and evasion were widespread. 16/26

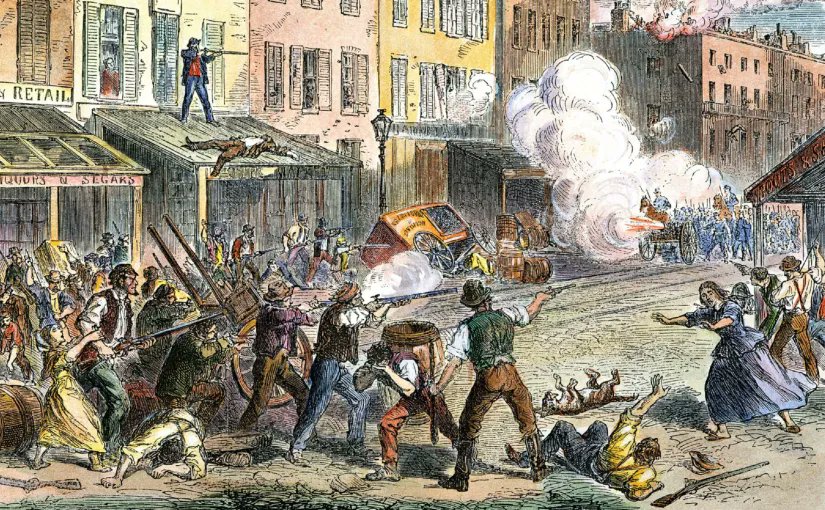

The conscription act had passed in March 1863. But, as in New York, trouble started in July, when provost marshals actually began to enforce the draft. In Boston, when a marshal attempted to serve draft notices in an Irish neighborhood, a crowd attacked. 17/26

The struggle quickly turned into a riot. The mob battled police with bricks and bottles, kicks and punches. As with the New York riot, the widespread participation of women and children was noted. 18/28

The specter of the catastrophic New York riot loomed over Massachusetts officials. They responded quickly, mobilizing the entire Boston police force, and calling out the militia – including infantry, dragoons, and artillery units. 19/28

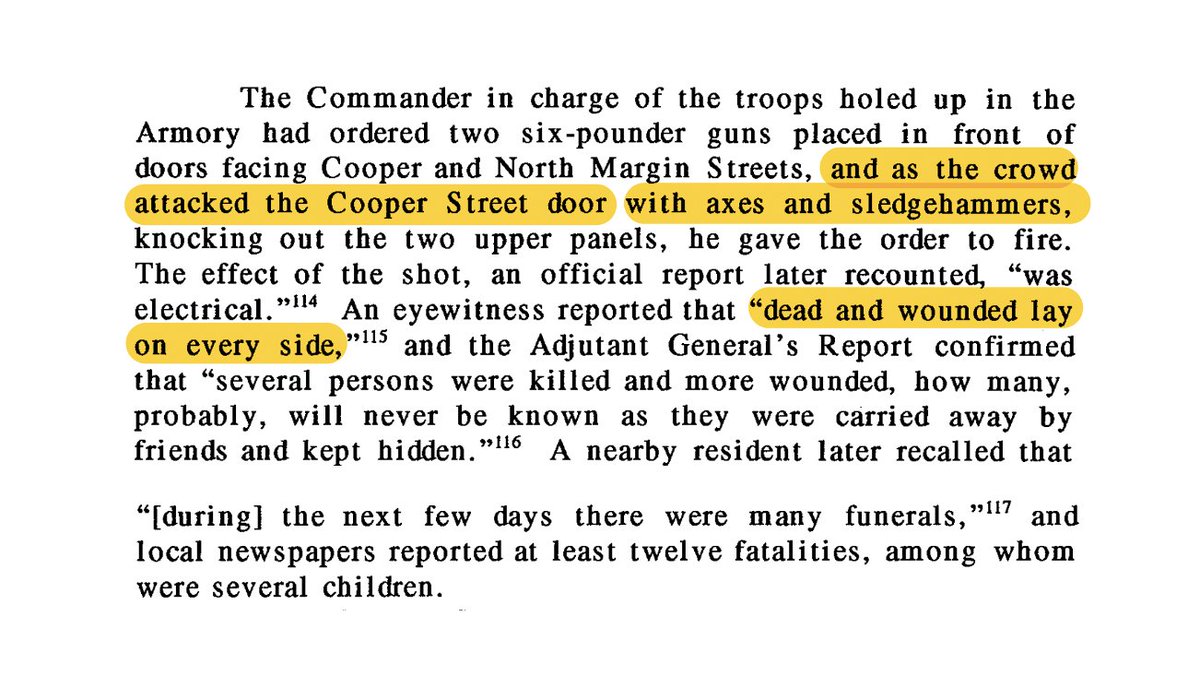

The situation became critical when the rioters attempted to storm the Cooper Street armory - It was feared they would seize the weapons and cannon inside. A stone’s throw from the Paul Revere House and the Old North Church, Boston again seemed on the brink of rebellion. 20/28

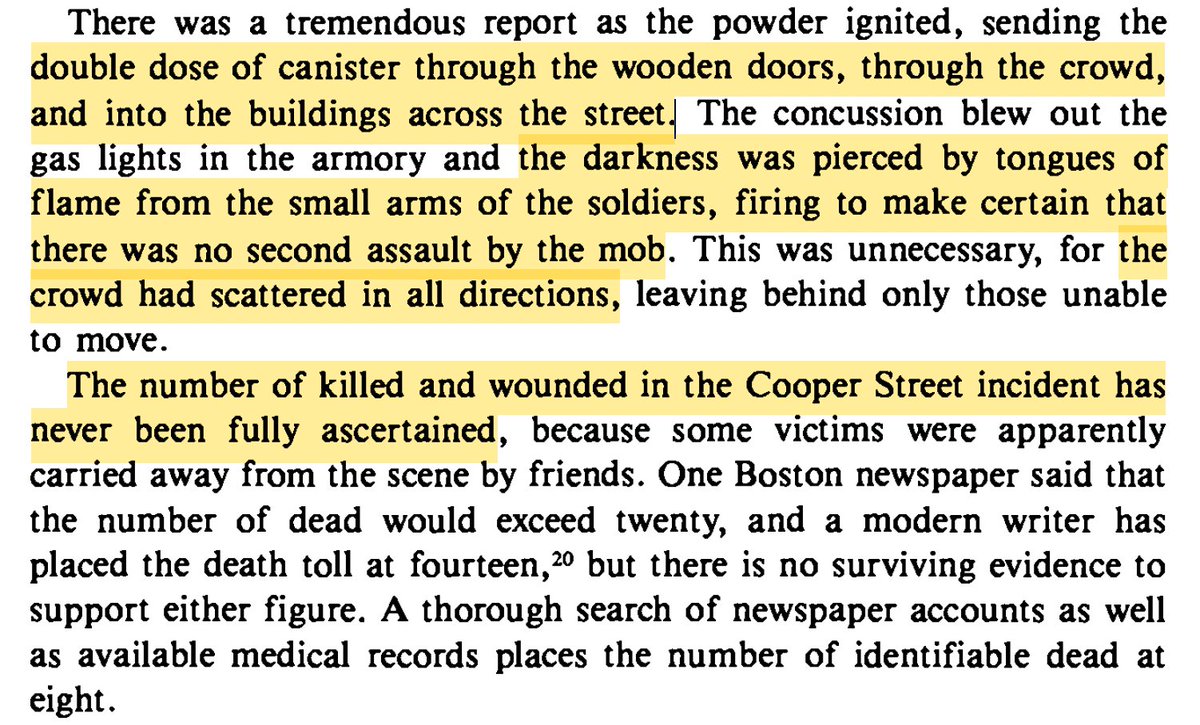

The mob repeatedly charged, hurling bricks, and attempting to smash their way in. As the doors of the armory seemed about give way, Major Cabot, the commander on the scene, felt he had no choice - His cannon opened fired, point-blank, with double-shotted canister. 21/28

The canister blasted the rioters and broke the attack on the armory. The number killed could never be confirmed, but included at least four children. Many of the killed were dragged away by the crowd and never identified. 22/28

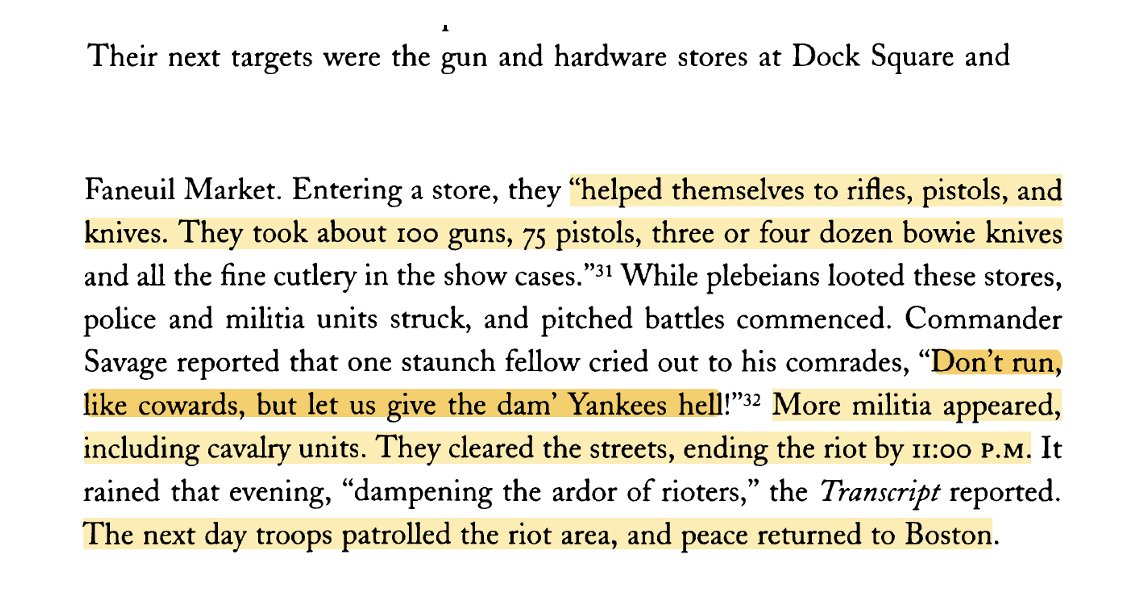

But the disturbance was not quite over – the rioters broke into nearby gun and hardware stores searching for weapons. In pitched battle, they were driven off by the militia, including cavalry units. The streets were cleared, and peace was restored to the city. 23/26

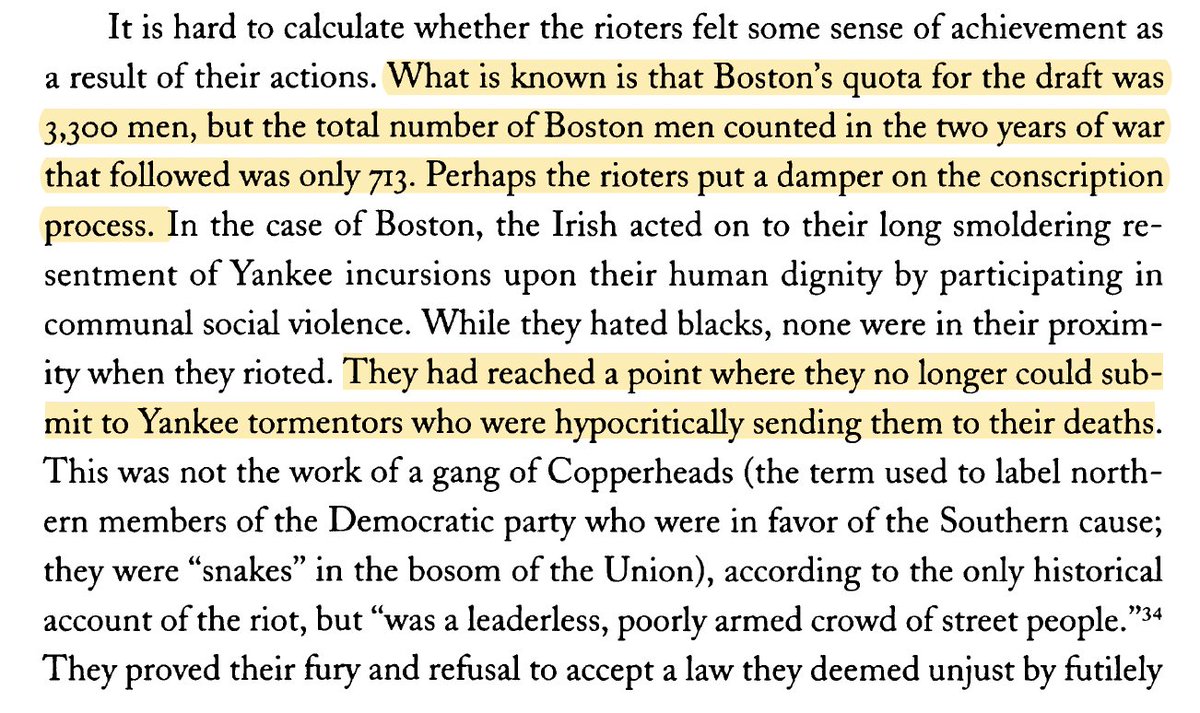

The riots and resistance to the 1863 conscription may have had an impact – the number of men conscripted fell far below the draft quotas.

24/26

24/26

While some measure of calm had been restored to the streets of Boston, peace between the Boston’s Irish and Yankee elites of Massachusetts was not forthcoming. Conflict would continue at the ballot box, and later on the school committees, far into the future. 25/26

Some historians theorized that the mass evasion and resistance to the draft and may have been a reflection of a broader, deeper resistance by more traditional cultures to the industrialization and modernizing trends of Yankee-dominated American society.

/fin

/fin

A related thread:

https://x.com/s_decatur/status/1677760117905711104

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh