We CT scanned an Apple Vision Pro! We also scanned two Meta headsets. Here’s what we found inside, and what it says about the two companies’ approach to AR/VR and to hardware development in general. 🧵

Here are our industrial CT scans of the Meta Quest Pro and Meta Quest 3 headsets. If you want to explore these scans, head to . Now let’s see what we found… lumafield.com/article/apple-…

Apple and Meta have taken different approaches to the market: the Vision Pro is a premium technology showcase for early adopters, while the Meta headsets are priced for accessibility in order to get as many people into the metaverse as possible.

Quick background on industrial CT: scanners like the @Lumafield Neptune use the same technology as medical CT scanners, taking X-ray images from different angles to create a detailed 3D model. Industrial scanners have a different form factor (fully enclosed in a cabinet to shield operators from X-rays) and can produce scans at higher resolution than medical scanners. When we visualize industrial CT scans, we can scrub through slices (the way most radiologists read medical CT scans) but we can also inspect them as freeform 3D models. CT scans can differentiate materials by density, and analysis software like @Lumafield Voyager can strip away lower-density material like plastic to isolate higher-density material, like the copper in electronics. Now back to the AR headsets…

The product development process is a series of tradeoffs, as designers and engineers iterate to balance original vision against the reality of manufacturing. Apple famously prioritizes design, challenging its engineers to hit aggressive targets without compromising on form.

The Vision Pro is a great illustration. It has a curvilinear enclosure that isn’t ideal for fitting large PCBAs. As a result, its main board is split into two angled sections. The Metas have blockier outer profiles, which allows their main boards to fit without being divided.

The Vision Pro also has lots of details that are expensive to implement but give it a more unified user experience. Here’s the motor and worm gear assembly that slides the left lens to automatically align it with the wearer’s pupils. There’s a mirrored assembly on the right.

Floating in front of each lens is a ring of small, very dense objects. These are the magnets that hold the Vision Pro’s optional, custom-made correctional lenses. The Meta headsets are simply designed to let users wear their own glasses.

The Meta headsets ship with handheld controllers. These are quite complex, with electronics on several differently-angled planes to support an ergonomic form factor. In our scans, the large lithium-ion battery in the handle stands out.

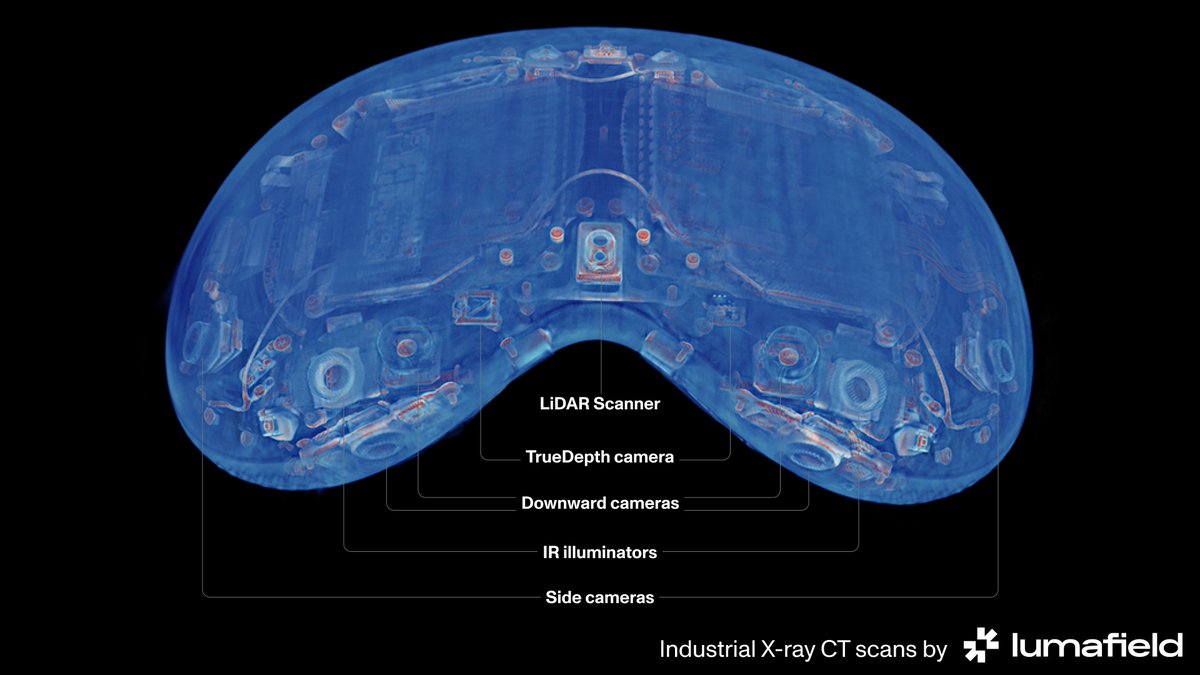

The Vision Pro takes a different approach: it’s controlled by a combination of eye and hand tracking. The headset is loaded with sensors to make this work. Here are some of the cameras and IR illuminators that help the VP track its user’s hands.

All of these headsets produce lots of heat. The Meta Quest Pro has a unibrow-shaped heat pipe filled with a coolant that evaporates near hot electronics and condenses near a pair of fans. The Quest 3 has just a single fan and no heat pipe.

The Vision Pro has a pair of large fans sandwiched between its displays and its main PCBAs. Look at these huge bearings! They run silently, with vanes that both quiet the airflow and move air away from the wearer.

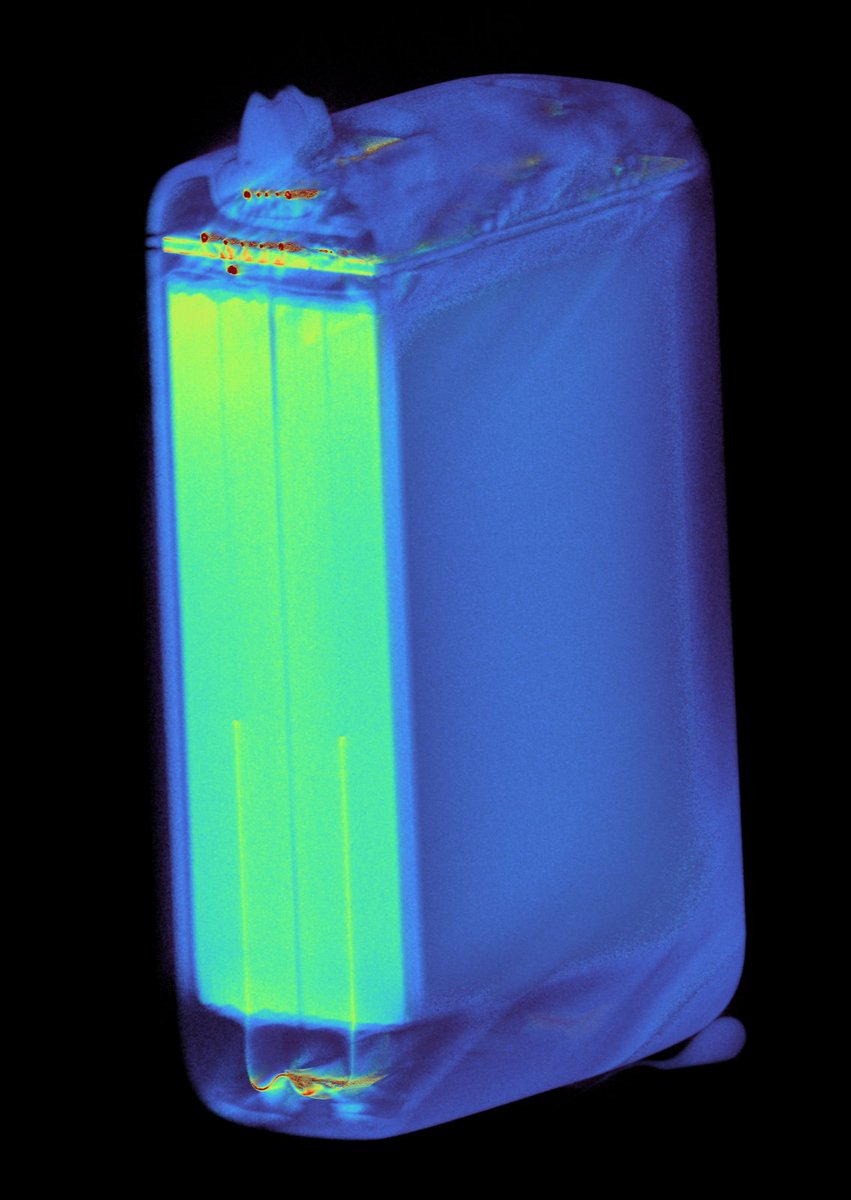

The Quest Pro’s battery is at the back of the headband. This helps balance the headset and moves the battery away from the heat of the headset’s processor. It also requires an unusual curved battery design. (The coil is a spring inside the headset tensioner knob.)

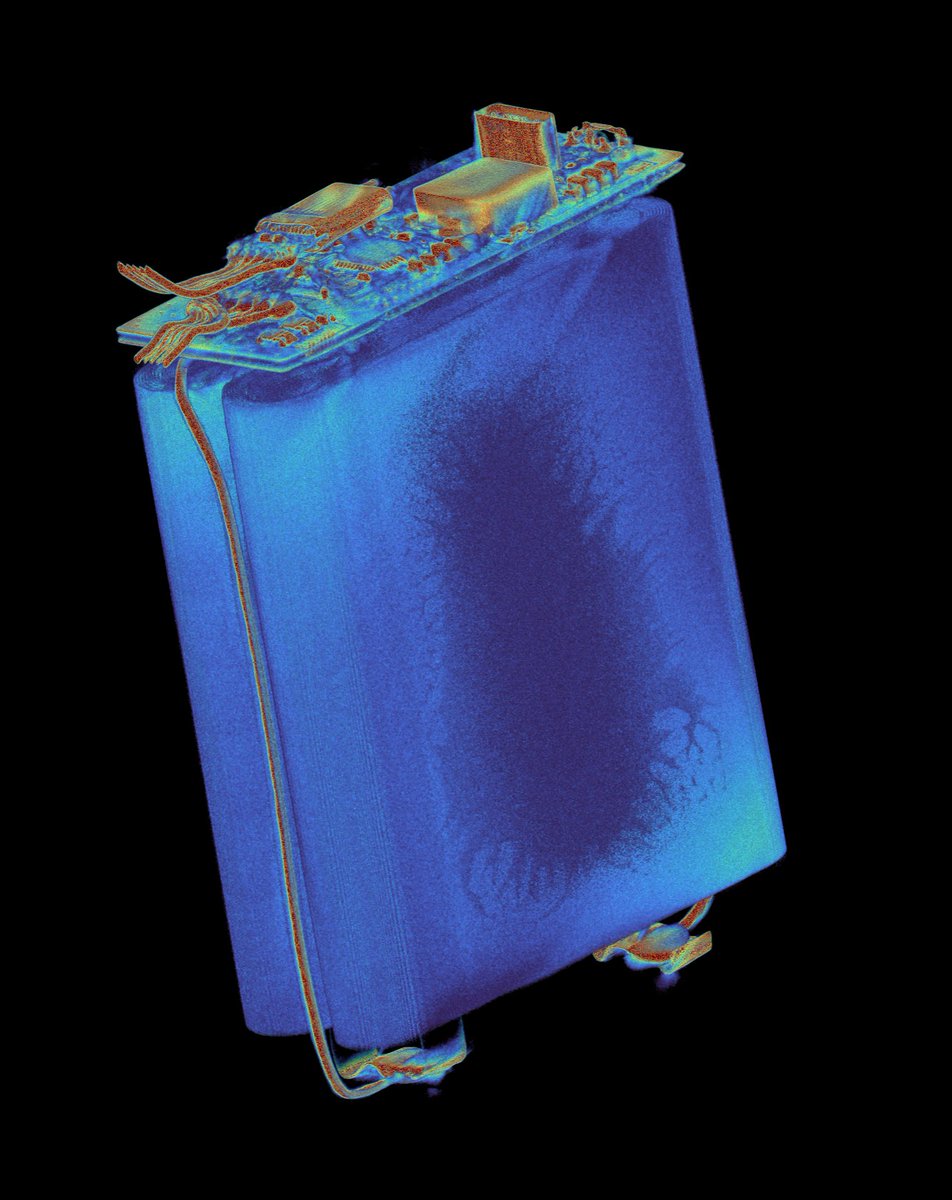

Our scan shows that each battery in the Quest Pro is attached to a single connector. But there’s also a mysterious set of pads on a flex PCB against each battery. Could these detect flexing/swelling of the battery? Or maybe they’re just pogo pin pads for testing or pre-charging?

The Quest 3’s battery is in the headset itself, where it fits against the main board. This is an advantage of the Quest 3’s relatively blocky enclosure: it’s easy (cost-effective) to layer in lots of rectangular components by just stacking them on top of each other.

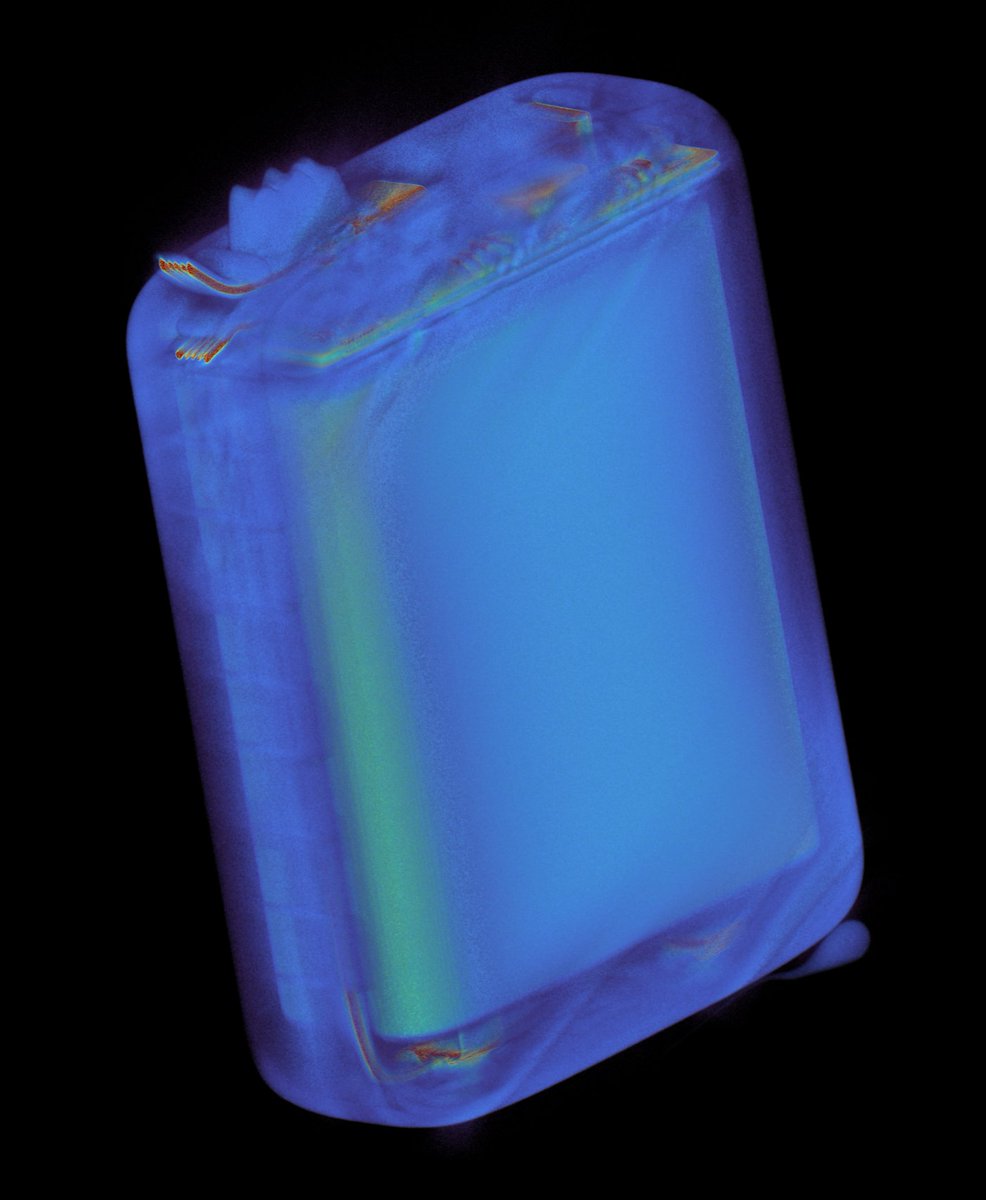

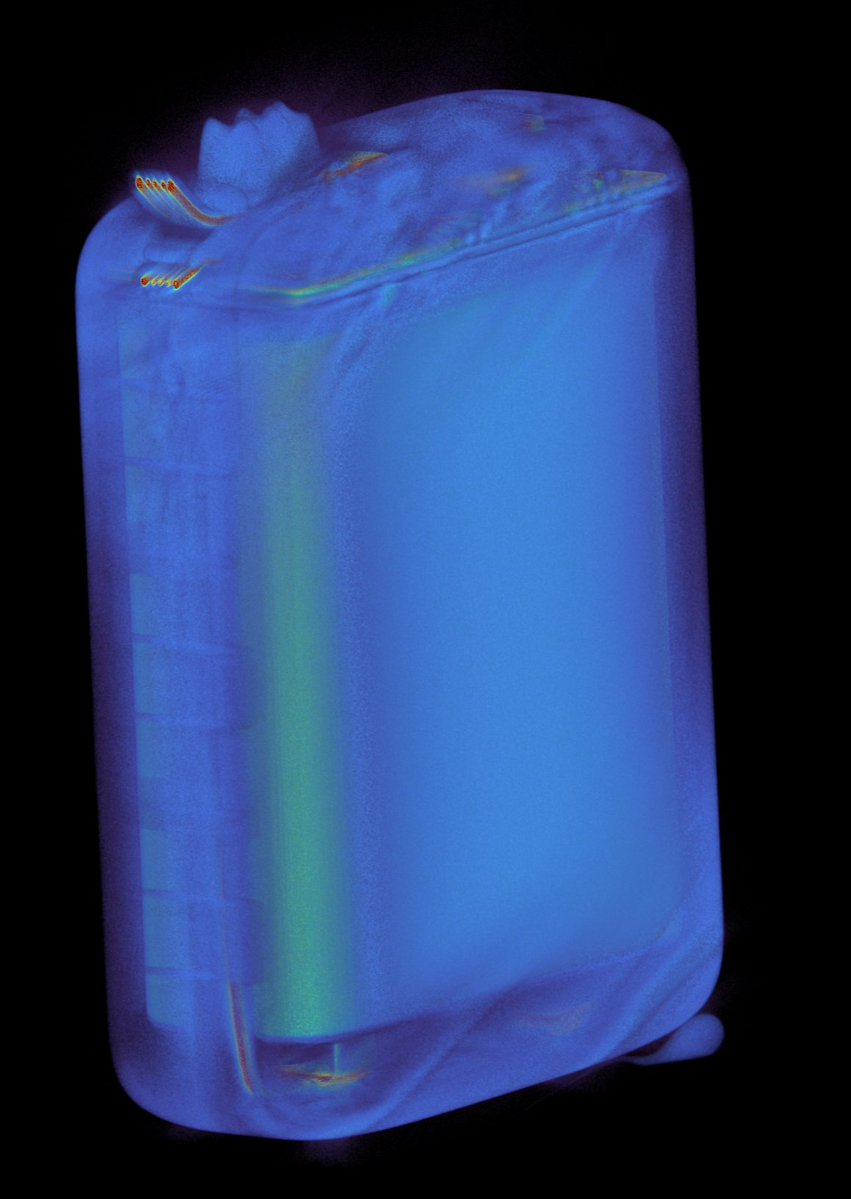

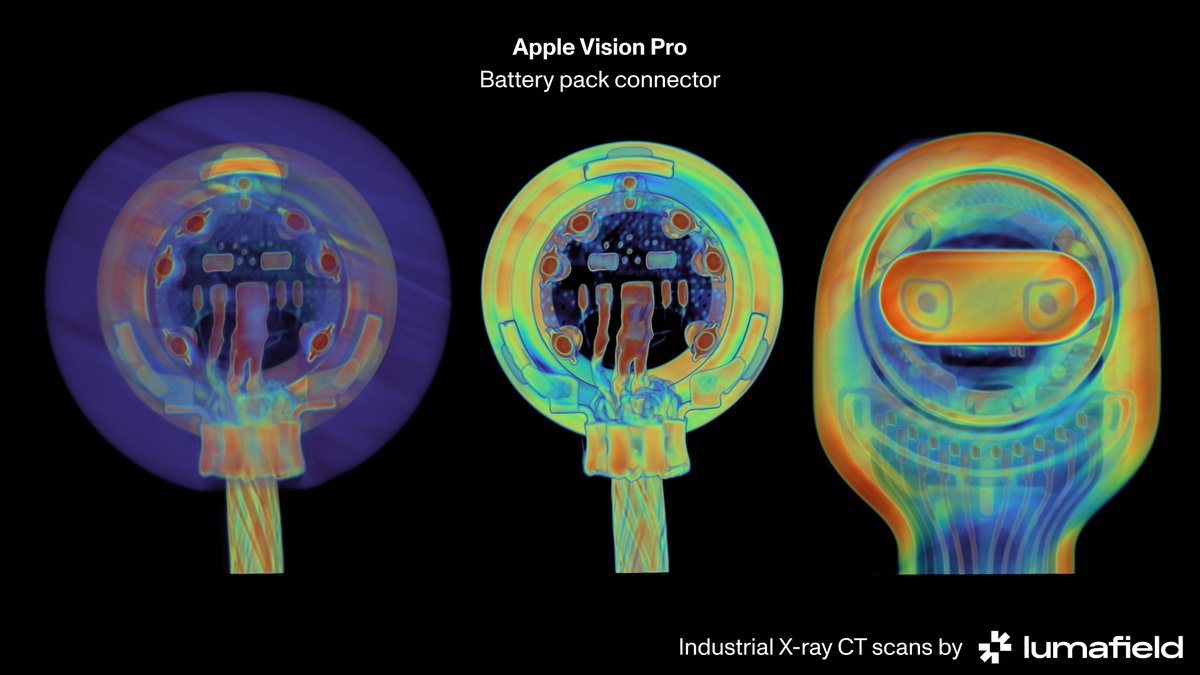

The Vision Pro’s battery is an externally-worn pack that contains 3 LiPo batteries with a honeycomb plate separating two of them. The plate could help with heat management, or it could just add rigidity to the assembly.

The Vision Pro battery pack uses a proprietary connector that’s pretty wild. This is the kind of thing engineers can develop when they have unlimited resources.

If you have a Vision Pro or Meta Quest, try opening Voyager on it! Here are links directly to the scans:

Vision Pro:

Quest Pro:

Quest 3: app.lumafield.com/project/606210…

app.lumafield.com/project/1ba44a…

app.lumafield.com/project/ae5aa2…

Vision Pro:

Quest Pro:

Quest 3: app.lumafield.com/project/606210…

app.lumafield.com/project/1ba44a…

app.lumafield.com/project/ae5aa2…

We also worked with the folks at @JigSpace to view one of our scans in 3D (this is a Luer lock–check out the thread for more on how these ingenious medical connectors work).

https://x.com/JonBruner/status/1773474799777681808

Explore these scans, and read more detail on the design of these headsets, here: lumafield.com/article/apple-…

Want to learn about industrial CT and how it’s used? Check out our explainer video here:

Wish you had watched a video version of this instead of reading a long Twitter thread? Here you go.

So you've made it to the end of a very long thread about industrial CT. Would you like to work at Lumafield? We're hiring in engineering, sales, and marketing! lumafield.com/careers

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh