This painting is over 100 years old.

It was made by a Swedish illustrator called John Bauer, one of the most important artists you've never heard of.

His revolutionary art influenced everything from graphic novels to animated films to video games, and here's why...

It was made by a Swedish illustrator called John Bauer, one of the most important artists you've never heard of.

His revolutionary art influenced everything from graphic novels to animated films to video games, and here's why...

John Bauer had a short but wonderfully creative life that ended in tragedy.

He died in 1918, at the age of just 36, along with his wife and son in a shipwreck on Lake Vättern.

But, in the time he was given, Bauer gave plenty back to the world.

He died in 1918, at the age of just 36, along with his wife and son in a shipwreck on Lake Vättern.

But, in the time he was given, Bauer gave plenty back to the world.

Bauer, who spent his schooldays doodling caricatures, studied at the Royal Swedish Academy of Arts.

There he set himself the goal of finding a new way to illustrate fairy tales, especially for children — he believed they had become conventionalised and lifeless.

There he set himself the goal of finding a new way to illustrate fairy tales, especially for children — he believed they had become conventionalised and lifeless.

See, throughout the 19th century illustration had been a sort of knock-off version of "Real Art".

Illustrators were beholden to the paintings of the Renaissance and the Academies, and they used a watered-down version of these styles to illustrate childrens' stories:

Illustrators were beholden to the paintings of the Renaissance and the Academies, and they used a watered-down version of these styles to illustrate childrens' stories:

Other illustrators were perhaps too reverential of Medieval and Renaissance woodcuts by the likes of Albrecht Dürer.

Again, these are not bad works of art, but Bauer was right — these illustrations feel somewhat lacking in life, lacking in magic.

Again, these are not bad works of art, but Bauer was right — these illustrations feel somewhat lacking in life, lacking in magic.

John Bauer changed all that.

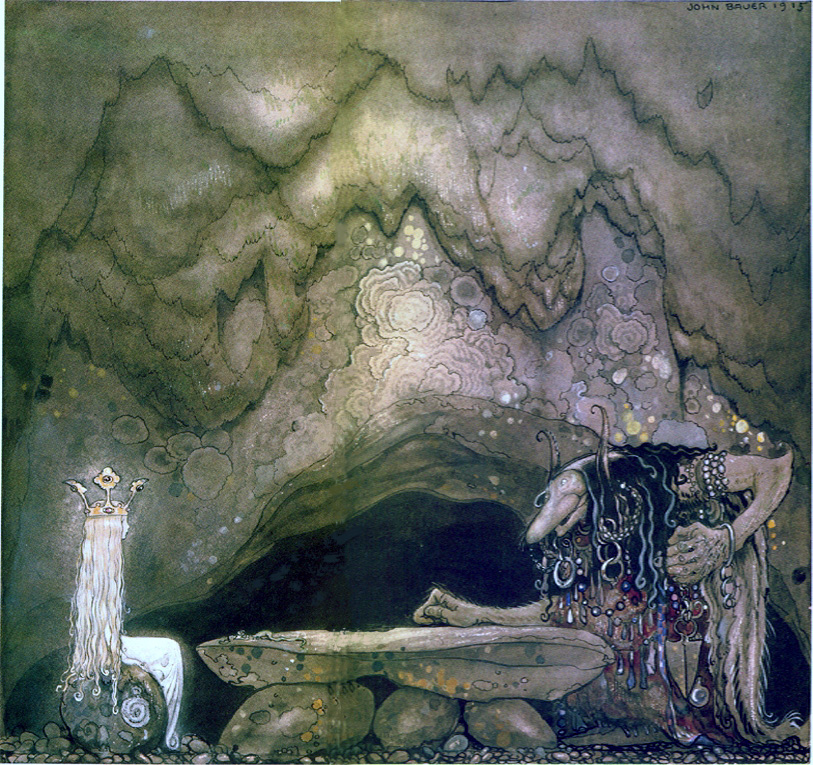

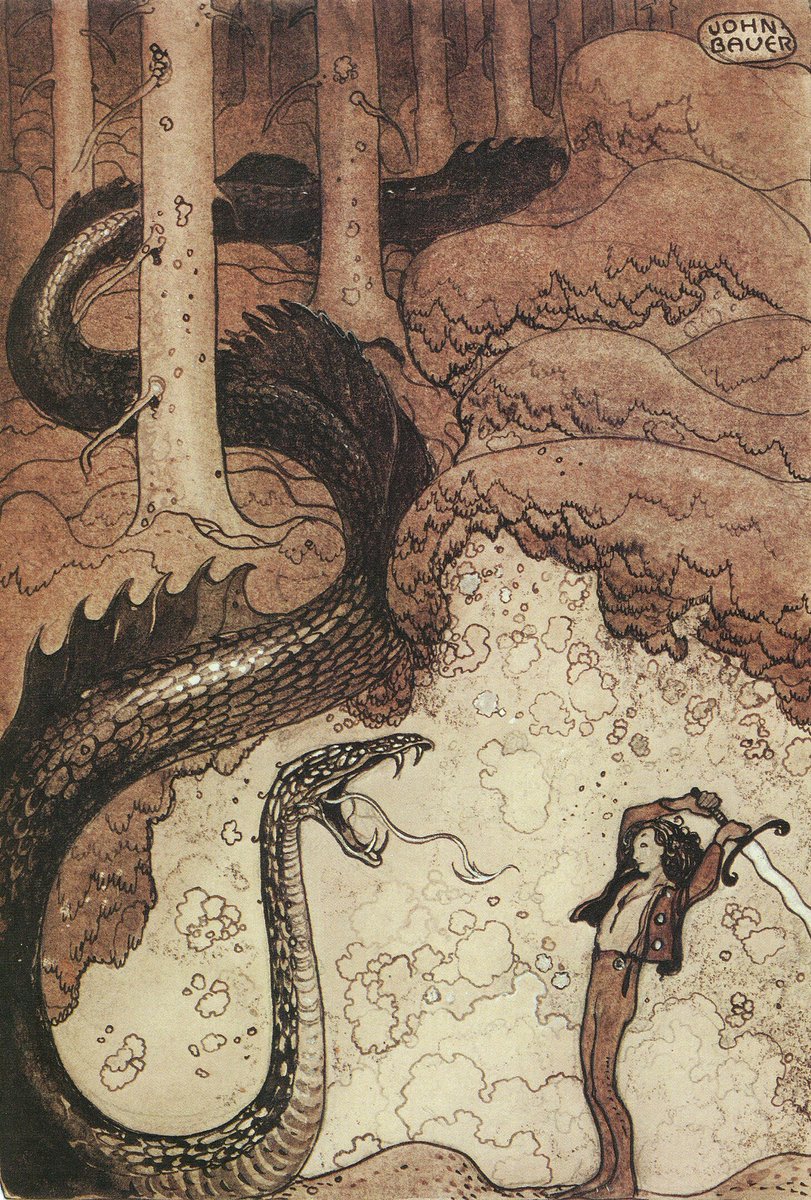

His illustrations of traditional Swedish folk tales, along with stories from Germanic mythology, were unlike anything else being made in Europe at the time.

His work was childlike without being childish and fantastical without being twee.

His illustrations of traditional Swedish folk tales, along with stories from Germanic mythology, were unlike anything else being made in Europe at the time.

His work was childlike without being childish and fantastical without being twee.

Bauer's heavily stylised worlds were, and remain, utterly enchanting.

Somehow he found a way to breathe new life into the fairytale tropes of trolls, fairies, knights, maidens, goblins, and wizards without relying on the familiar forms of other illustrators.

Somehow he found a way to breathe new life into the fairytale tropes of trolls, fairies, knights, maidens, goblins, and wizards without relying on the familiar forms of other illustrators.

In short, John Bauer gave illustration a visual language of its own.

No longer would illustrations be made in reference to the art of the Academies or to the Renaissance.

Bauer wanted to make illustration a distinct form of art, and he succeeded:

No longer would illustrations be made in reference to the art of the Academies or to the Renaissance.

Bauer wanted to make illustration a distinct form of art, and he succeeded:

How did he do it? Notice that Bauer used unusual compositions.

His figures are often squashed into the frame, or positioned at the extreme of one side, leaving swathes of empty space.

An unusual choice, but it gives these images a suitable sense of mystery and strangeness.

His figures are often squashed into the frame, or positioned at the extreme of one side, leaving swathes of empty space.

An unusual choice, but it gives these images a suitable sense of mystery and strangeness.

He also liked to depict scenes in a way that was almost two-dimensional.

This harked back to Medieval art, but Bauer did not merely imitate — he reapplied it in a new way.

These illustrations look rather similar to platformer video games:

This harked back to Medieval art, but Bauer did not merely imitate — he reapplied it in a new way.

These illustrations look rather similar to platformer video games:

You can see why John Bauer has been so influential; thousands grew up with his drawings, which were published in the annual anthology of Swedish folkore called "Among Gnomes and Trolls".

The design of parts of Minecraft was inspired by his depictions of forests and caves:

The design of parts of Minecraft was inspired by his depictions of forests and caves:

He was never happy with his own work, always haunted by self-doubt, and felt that he had never achieved his goal of closing the gap between "real art" and "illustration".

But, to others, he *had* shown that the latter could be just as good as the former, in its own way.

But, to others, he *had* shown that the latter could be just as good as the former, in its own way.

Because from those rather drab 19th century illustrations something new had emerged.

Bauer's fairytales are genuinely compelling, even frightening, and darkly magical.

These look familiar to us because this sort of illustration has become common; back then it was revolutionary.

Bauer's fairytales are genuinely compelling, even frightening, and darkly magical.

These look familiar to us because this sort of illustration has become common; back then it was revolutionary.

The full influence of Bauer is hard to quantify.

No doubt he was immensely influential in his homeland, and people like Brian Froud and Neil Gaiman have acknowledged his work.

But Bauer's impact on everything from animation to video games is likely far greater than we realise.

No doubt he was immensely influential in his homeland, and people like Brian Froud and Neil Gaiman have acknowledged his work.

But Bauer's impact on everything from animation to video games is likely far greater than we realise.

He represents a turning point from the decidedly stale world of 19th century illustration to the modern era whereby illustration — including comics, graphic novels, animated films, and most recently video games — have become a fully fledged genre of their own.

Bauer was not alone in doing this, of course.

In Britain there was Arthur Rackham, who like Bauer illustrated tales from folklore and the operas of Richard Wagner also.

In Britain there was Arthur Rackham, who like Bauer illustrated tales from folklore and the operas of Richard Wagner also.

Meanwhile in France there was Henri Toulouse-Lautrec.

His speciality was posters rather than illustrations, but even so he was still part of this broader, continental revolution in graphic design that expanded art beyond the world of murals and canvasses:

His speciality was posters rather than illustrations, but even so he was still part of this broader, continental revolution in graphic design that expanded art beyond the world of murals and canvasses:

And another important figure was Gustave Doré.

He was perhaps the most prolific illustrator of the 19th century, producing thousands of fabulous images to illustrate everything from the Bible to epic poems like Orlando Furioso or Paradise Lost, along with Don Quixote.

He was perhaps the most prolific illustrator of the 19th century, producing thousands of fabulous images to illustrate everything from the Bible to epic poems like Orlando Furioso or Paradise Lost, along with Don Quixote.

Doré was dismissed as a "mere" illustrator by the artistic establishment.

But he, like Bauer, created art that was beloved by the people who read and loved these stories.

And so, in time, their belief in the artistic potential of "mere" illustration changed everything.

But he, like Bauer, created art that was beloved by the people who read and loved these stories.

And so, in time, their belief in the artistic potential of "mere" illustration changed everything.

There was also major influence from Japan.

When Japan's borders were forcibly opened to international trade in the 1850s and 1860s ukiyo-e — Japanese woodblock prints, made in the thousands for the popular market — flooded Europe.

They changed European art forever.

When Japan's borders were forcibly opened to international trade in the 1850s and 1860s ukiyo-e — Japanese woodblock prints, made in the thousands for the popular market — flooded Europe.

They changed European art forever.

But of all these many influences and great artists, it's hard to find one more original than John Bauer.

He breathed new life into illustration and, though we cannot say he singlehandedly created a new form of art, he clearly helped to do so... John Bauer achieved his dream.

He breathed new life into illustration and, though we cannot say he singlehandedly created a new form of art, he clearly helped to do so... John Bauer achieved his dream.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh