🧵PART 2 of my thread on the Supreme Court of Fla.'s decision in Planned Parenthood v. State, where it receded from precedent holding that our state constitution's right of privacy included abortion.

We'll talk about the court's inaccurate account of preexisting Fla. case law.

We'll talk about the court's inaccurate account of preexisting Fla. case law.

Part 1 reviewing the court's analysis of the text of Florida's privacy clause is here. 2/21

https://x.com/ajrichar/status/1775593677018054940

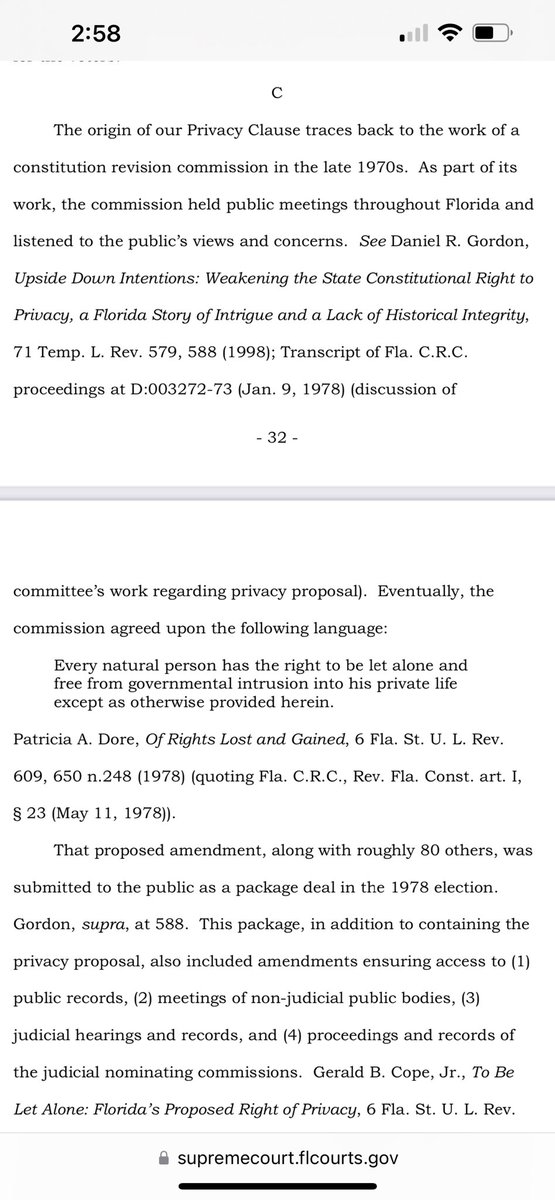

Before turning to the general Florida background, one more point about the text. On page 20, the court says that "free from governmental intrusion" into "private life" "can convey a similar meaning" to "let alone." The court does not interpret these phrases separately. 3/21

This is a violation of rules of construction, which are articulated in Scalia and Garner's authoritative book on textualism, Reading Law: [4/21]

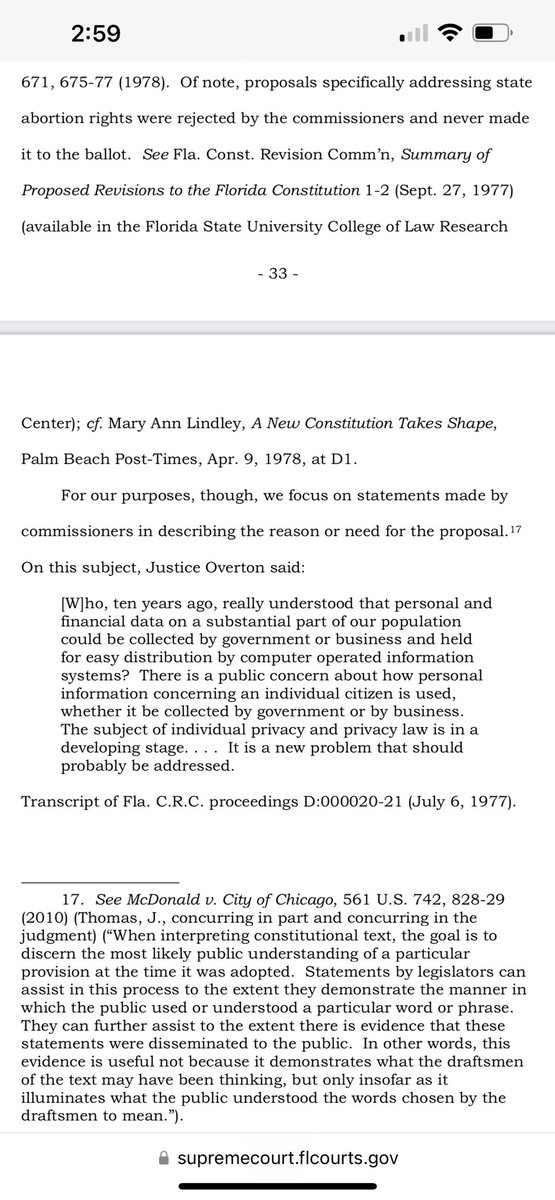

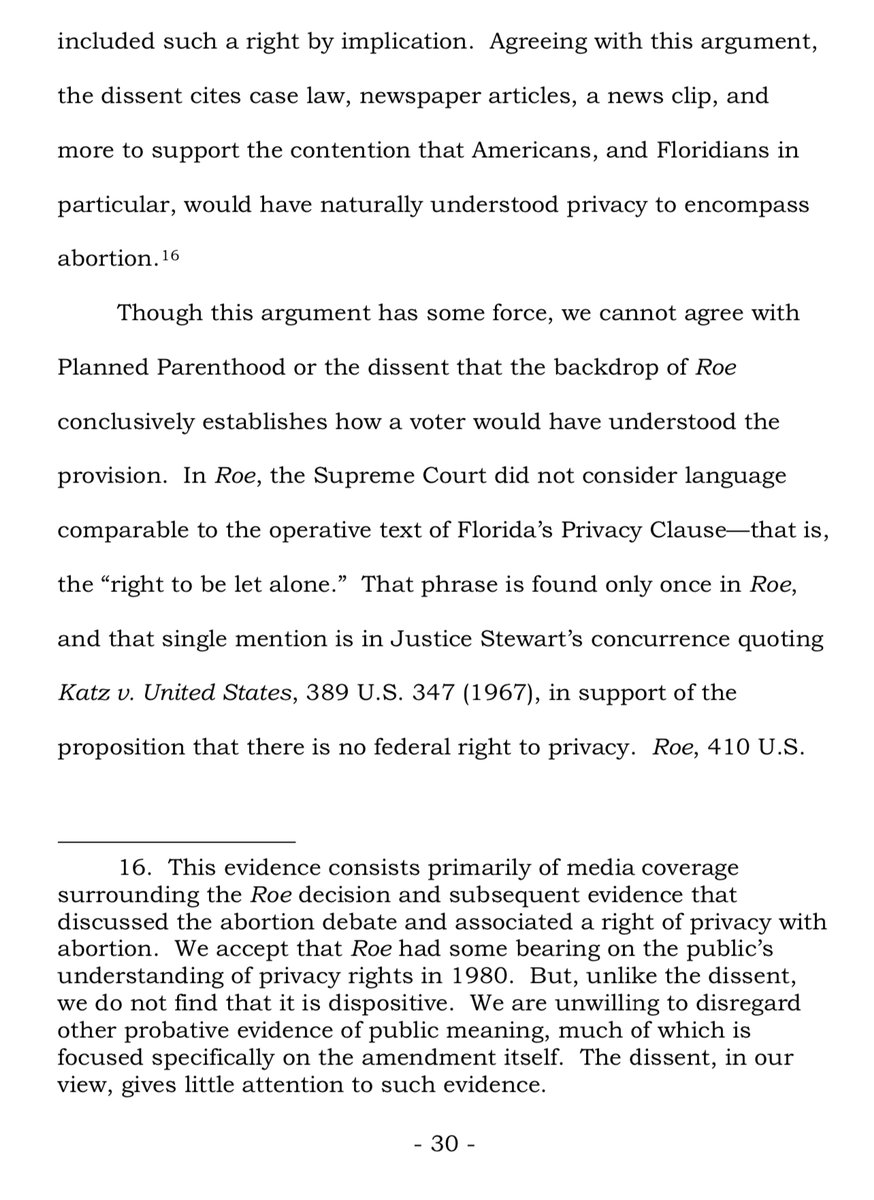

Onward. The majority's opinion contains two sections on general legal background, V(A) and (B). In this part of the thread, I'll focus on V(A). In the next, I'll look at V(B), where the court addresses Roe v. Wade. 5/21

3) FLORIDA CASE LAW ON "TO BE LET ALONE":

In V(A), the court looked at how the "right to be let alone" was understood in Florida law, i.e., its technical meaning. 6/21

In V(A), the court looked at how the "right to be let alone" was understood in Florida law, i.e., its technical meaning. 6/21

This narrow framing ignores the big picture: the plain and ordinary meaning of the term that long predated any association with the Warren and Brandeis article. I already refuted the idea that we should focus on a technical meaning in my article. 7/21

But it's worth mentioning a certain inconsistency. The court believes that this obscure technical meaning of "to be let alone" in Florida law is significantly probative of its OPM, while as discussed in the next part of the thread, it dismisses the effect of Roe v. Wade. 8/21

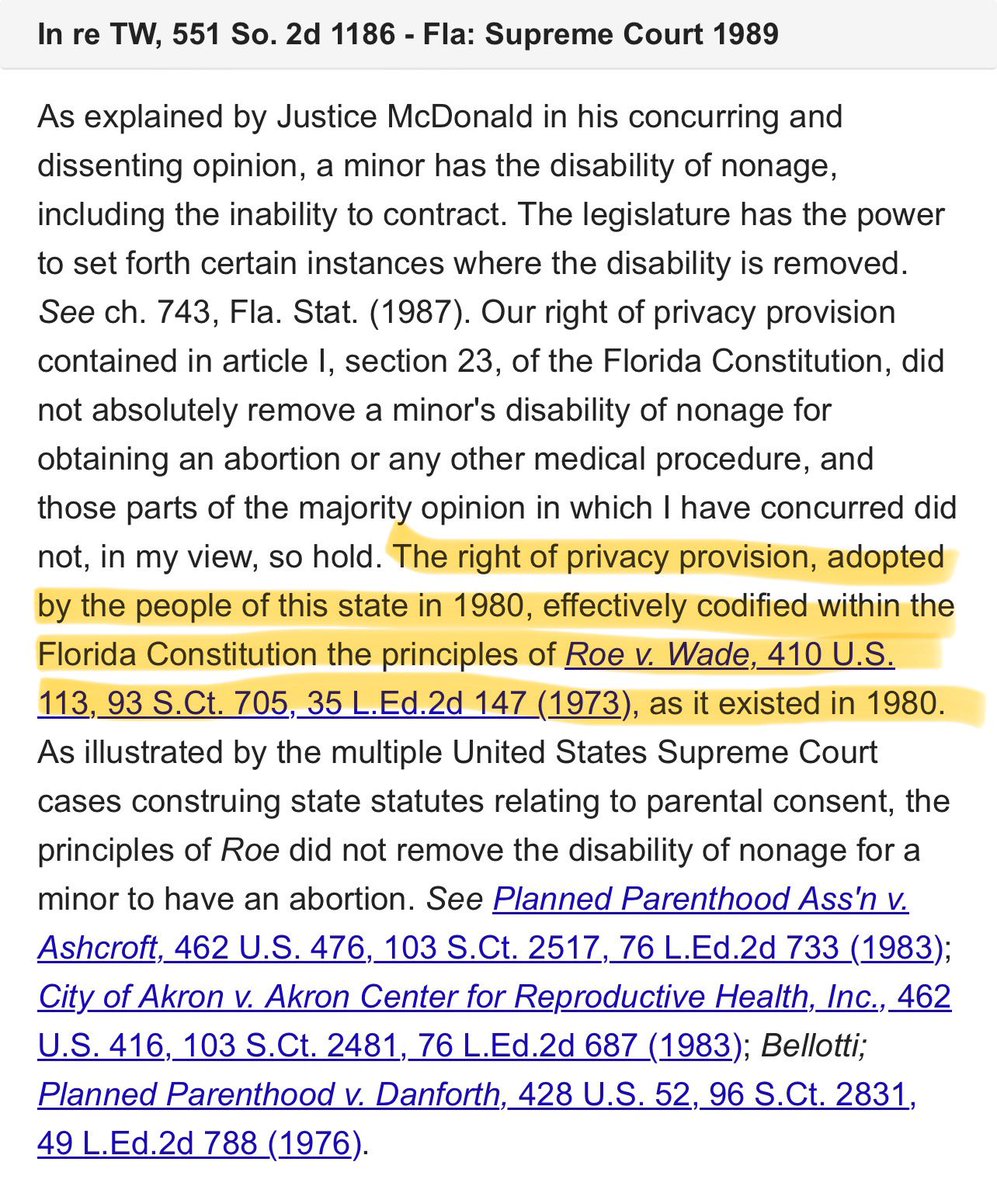

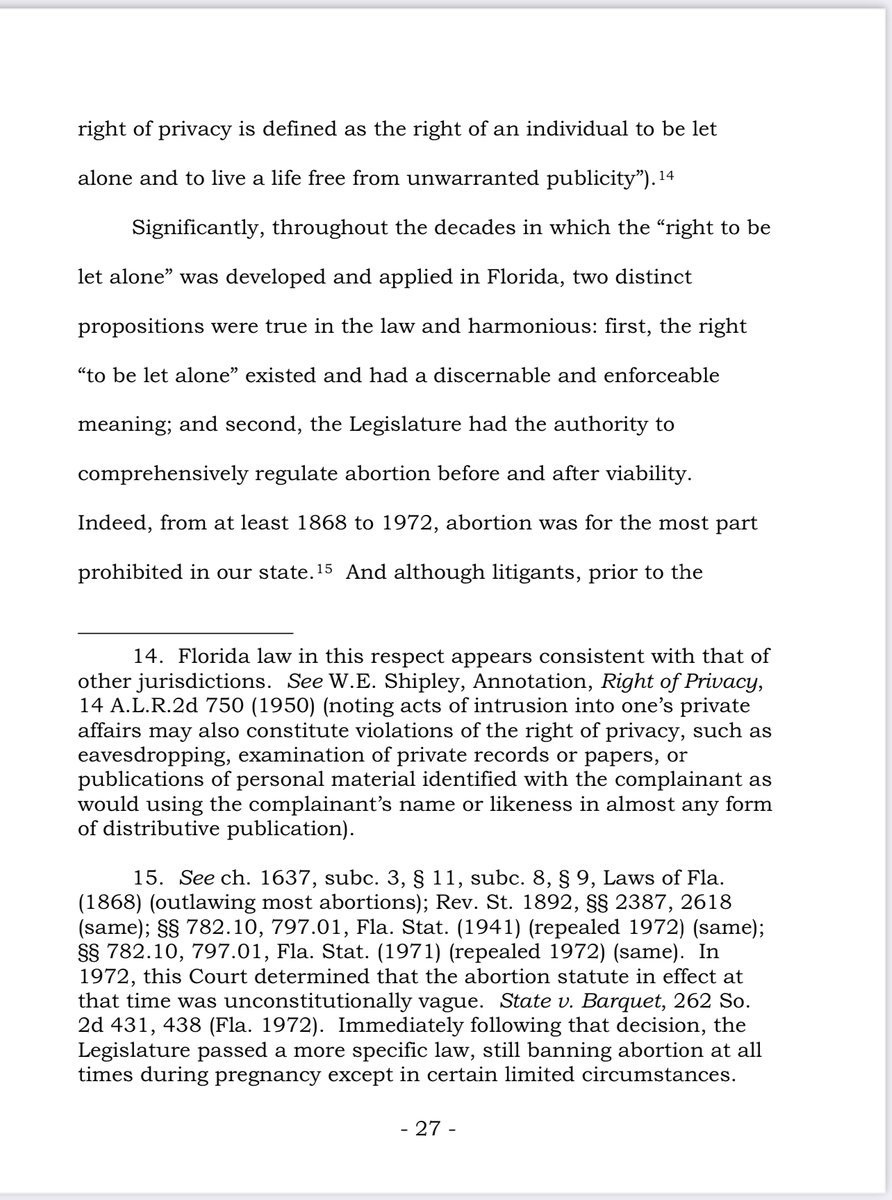

Even so, the court ignored other, relevant Florida cases on "to be let alone." It relied in large part on Cason v. Baskin (Fla. 1944), and some others, to conclude that "to be let alone" in Florida meant something like the right against the invasion of privacy. 9/21

In fact, on page 31, the court goes so far as to say "that the specific phrase used in the Privacy Clause had a consistent meaning in Florida law and had never once been interpreted to cover abortion rights."

This is an error, and a potentially significant one. 10/21

This is an error, and a potentially significant one. 10/21

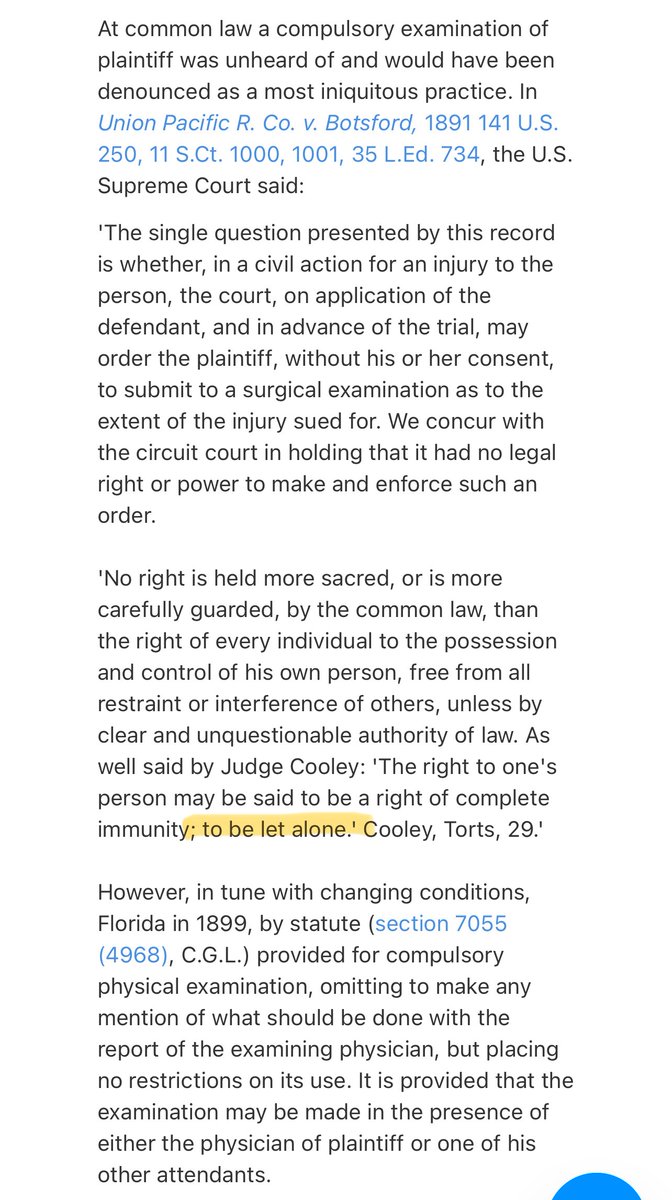

Although not involving abortion, a supreme court case four years before Cason, Fred Howland Inc. v. Morris (Fla. 1940), is relevant. It dealt with invasive compulsory medical examinations of plaintiffs. The supreme court said (): [11/21] case-law.vlex.com/vid/fred-howla…

This relation of the right "to be let alone" to a compelled medical evaluation is, obviously, not about the invasion of privacy, in the sense meant by the Planned Parenthood court. 12/21

But then we *do* have a case about abortion!

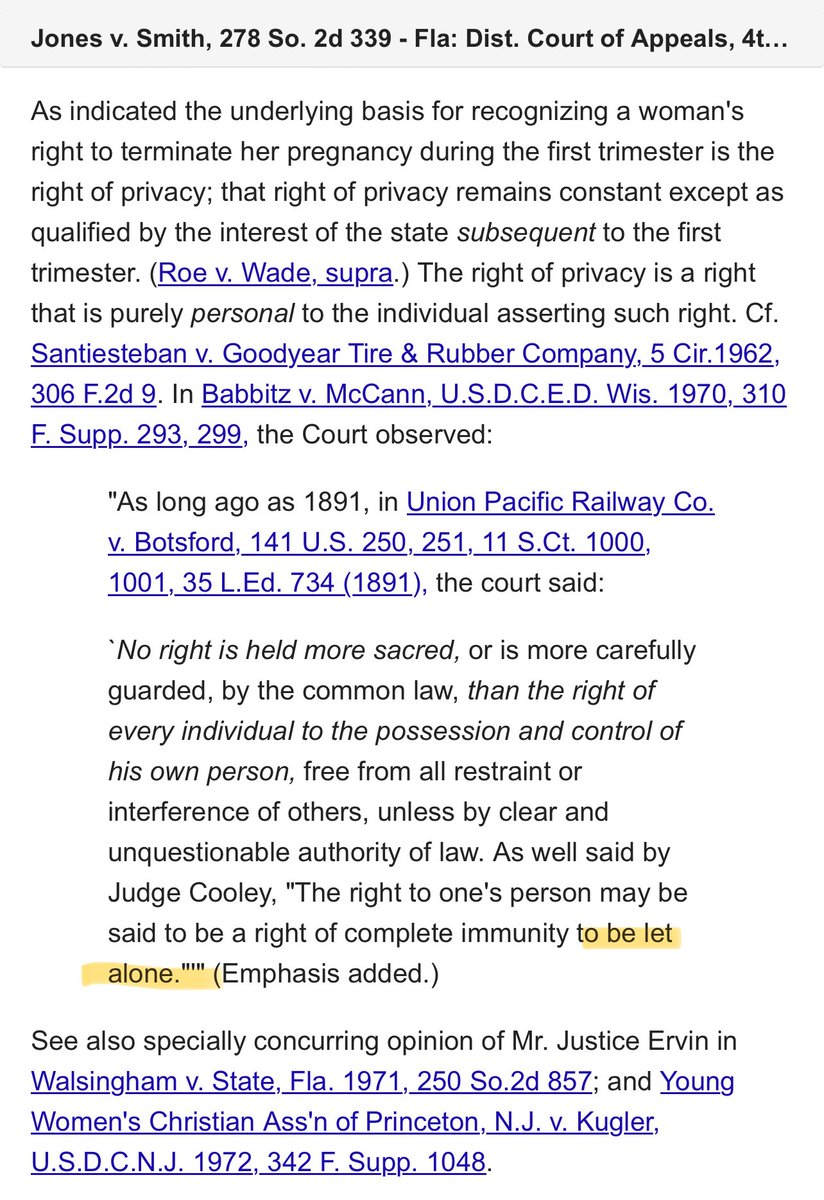

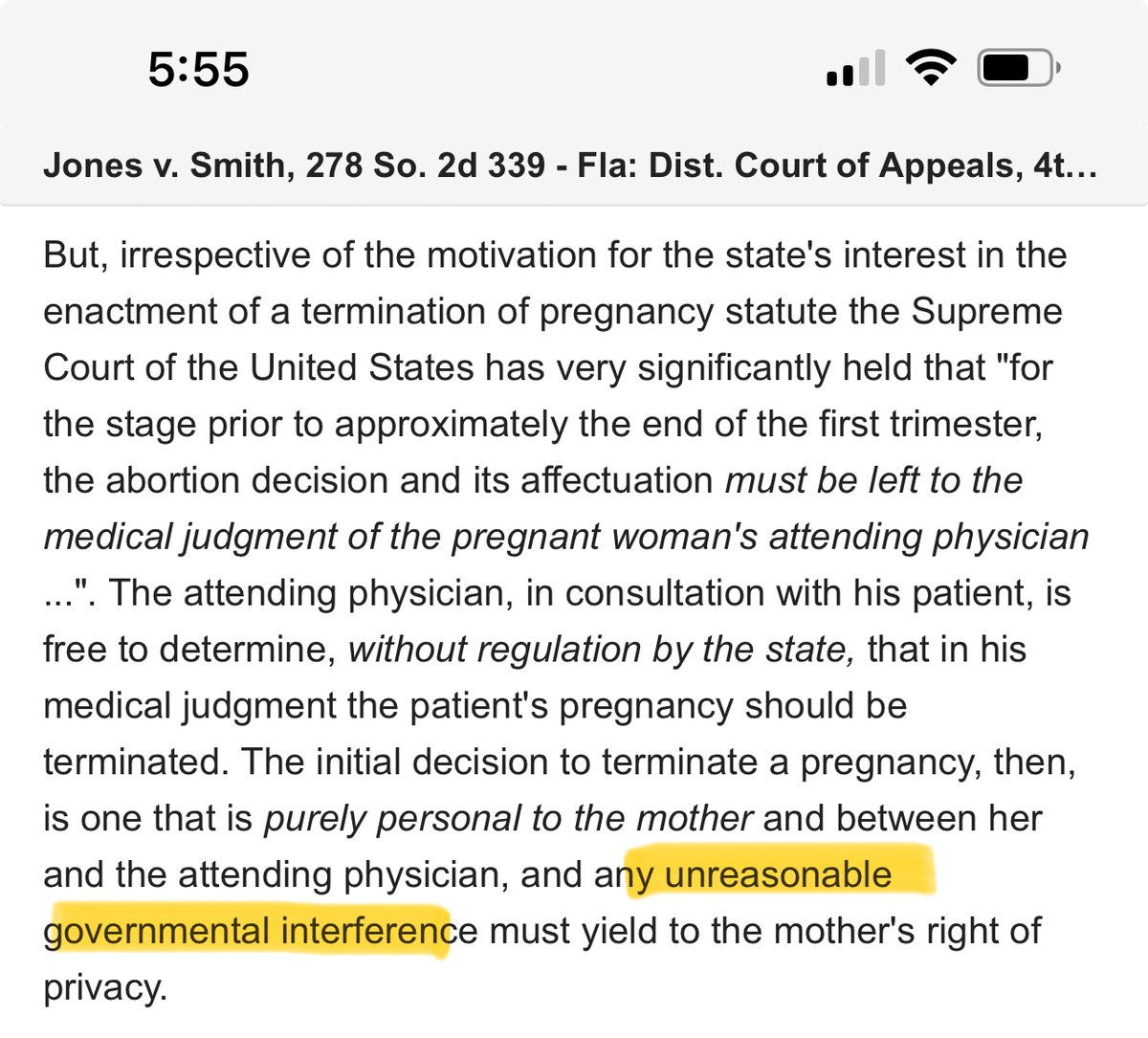

Jones v. Smith (4DCA 1973) was decided after Roe v. Wade (). The father of an unborn child tried to get a court to forbid the mother from obtaining an abortion. The appellate court rejected the attempt. 13/21scholar.google.com/scholar_case?c…

Jones v. Smith (4DCA 1973) was decided after Roe v. Wade (). The father of an unborn child tried to get a court to forbid the mother from obtaining an abortion. The appellate court rejected the attempt. 13/21scholar.google.com/scholar_case?c…

This case refutes the Planned Parenthood court's statement that the language that wound up in the privacy clause "had never once been interpreted [by Florida courts] to cover abortion rights."

There are two other relevant Florida cases mentioning "to be let alone." 15/21

There are two other relevant Florida cases mentioning "to be let alone." 15/21

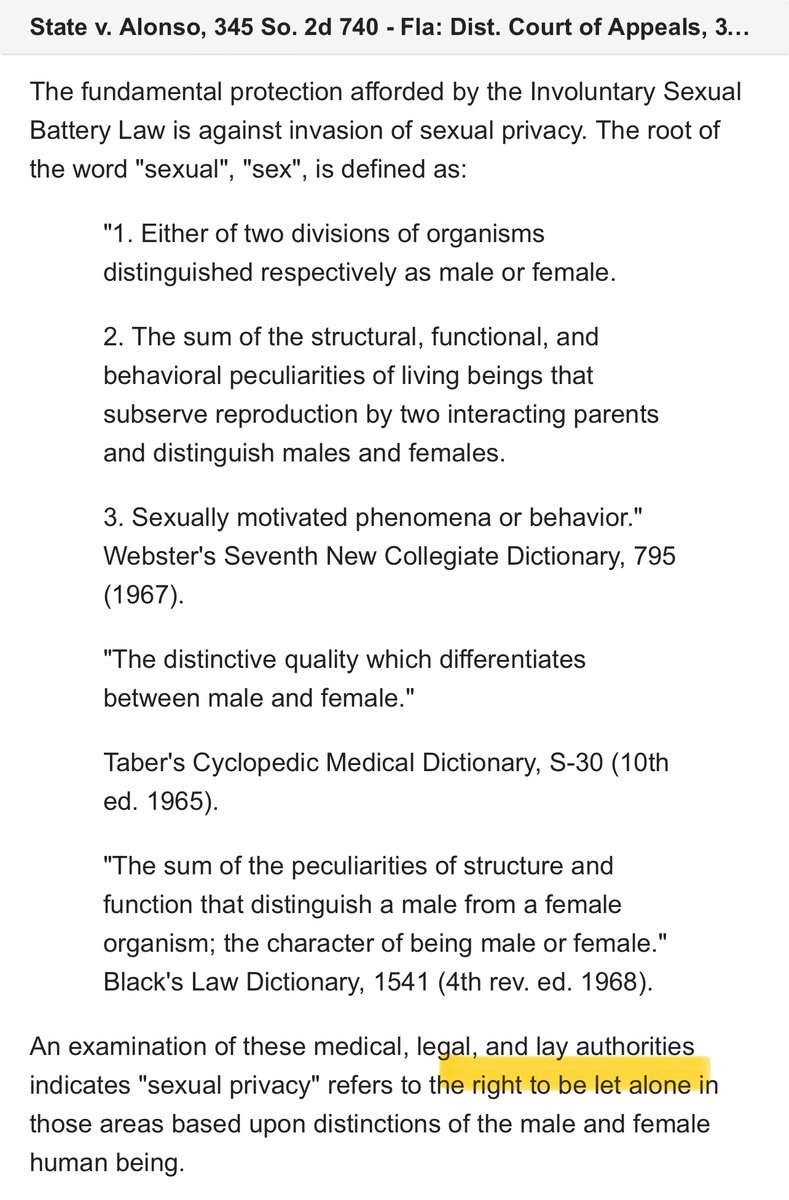

In 1977, another appellate court decided State v. Alonso (3DCA 1977) (). The prosecutions in Alonso were for sex crimes arising from unlawful abortions. The court said: [16/21] scholar.google.com/scholar_case?c…

In Alonso, the right "to be let alone" was related to sexual conduct -- again, not something to do with the invasion of privacy.

Finally, in 1979, another appellate court decided Rogers v. State Board of Medical Examiners (1DCA 1979) (). 17/21scholar.google.com/scholar_case?c…

Finally, in 1979, another appellate court decided Rogers v. State Board of Medical Examiners (1DCA 1979) (). 17/21scholar.google.com/scholar_case?c…

Rogers dealt with the regulation of the medical profession, but it discussed Roe v. Wade, mentioned "unreasonable governmental interference" in that discussion, and quoted Jones v. Smith. 18/21

The remainder of the Planned Parenthood court's discussion about the Florida legal background does not really seem to advance the court's argument, at least not once we see how the language in the privacy clause had actually been interpreted by Florida courts. 19/21

So as the court said, "[t]he phrase 'to be let alone' carries with it a rich legal tradition" in Florida -- just not the one the court says. The phrase "had a consistent meaning in Florida law," but a broad one. And it had been interpreted to cover abortion rights. 20/21

The court's statement that "the technical meaning of the terms contained in the provision" does "not support a conclusion that abortion should be read into the amendment's text" is based on an incomplete history.

NEXT: Thoughts on the court's analysis of Roe v. Wade & OPM. 21/21

NEXT: Thoughts on the court's analysis of Roe v. Wade & OPM. 21/21

@threadreaderapp unroll

P.S. To put a finer point on it: The FIRST TIME "to be let alone" appears in a FL decision, it's about a person's right against the govt.'s interference with his body -- NOT against unwanted publicity. Florida jurisprudence consistently related BOTH to the right to be let alone.

The Planned Parenthood majority undermined its own account of the law by citing State v. Eitel (Fla. 1969), which concerned the constitutionality of a statute requiring motorcyclists to wear helmets -- again, bodily autonomy (). scholar.google.com/scholar_case?c…

@threadreaderapp unroll

@threadreaderapp And another postscript. That the majority made the categorical statements about Florida law and omitted ANY discussion of the cases above is truly baffling because Justice Labarga’s dissent discussed Jones v. Smith specifically!!!

@threadreaderapp @threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh