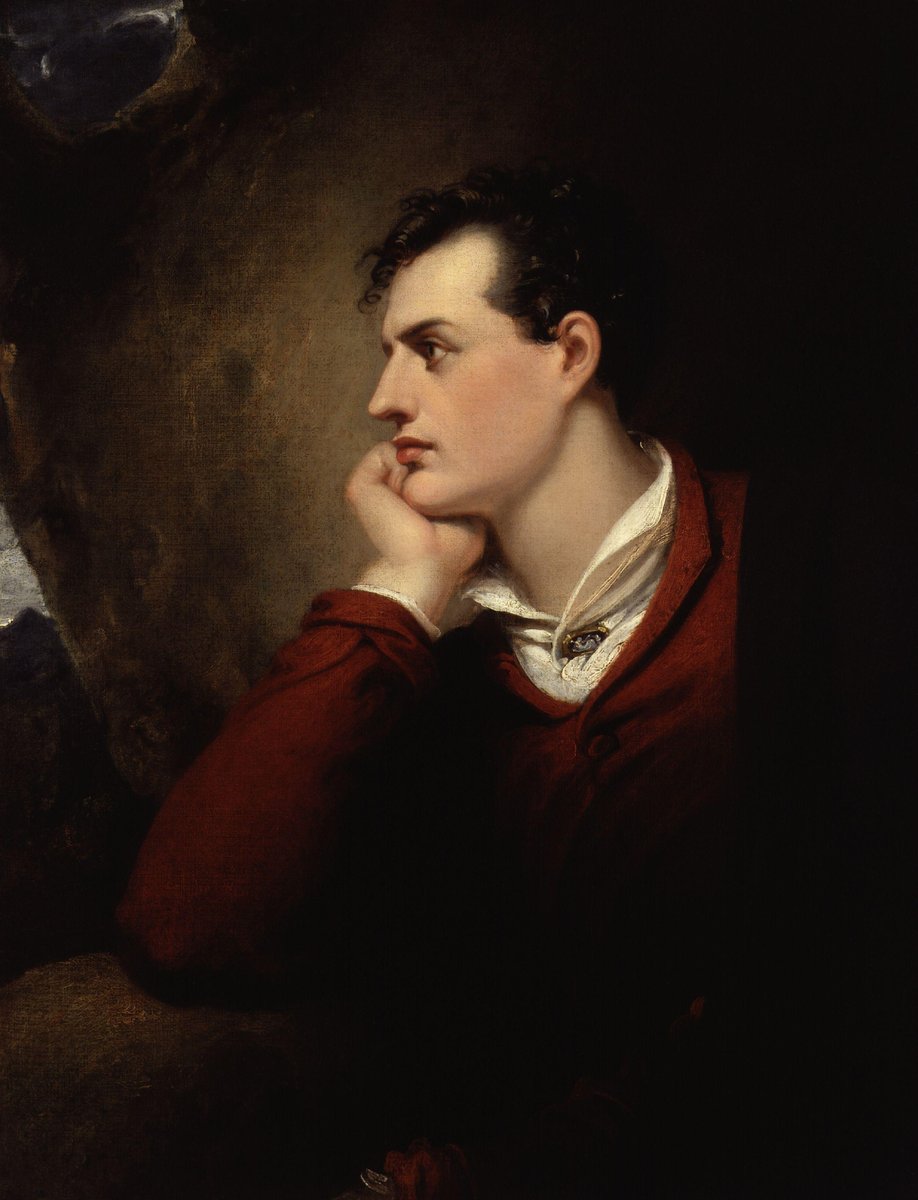

Exactly 200 years ago today one of history's most influential and controversial writers died.

He kept a pet bear at university, (allegedly) had an affair with his half-sister, fought for Greek Independence — and also wrote some poetry.

This is the story of Lord Byron...

He kept a pet bear at university, (allegedly) had an affair with his half-sister, fought for Greek Independence — and also wrote some poetry.

This is the story of Lord Byron...

Byron dominated 19th century European culture.

Artists including Hayez, Delacroix, and Turner painted scenes from his poems, and composers including Beethoven, Verdi, and Tchaikovsky set his work to music.

A cultural icon who has shaped literature for two centuries.

Artists including Hayez, Delacroix, and Turner painted scenes from his poems, and composers including Beethoven, Verdi, and Tchaikovsky set his work to music.

A cultural icon who has shaped literature for two centuries.

The details of the wild life of Lord Byron are impossible to retell in full.

But, in brief, George Gordon Byron was born in London in 1788 to a Scottish heiress, Catherine Gordon, and a philandering British army captain known as John "Mad Jack" Byron.

But, in brief, George Gordon Byron was born in London in 1788 to a Scottish heiress, Catherine Gordon, and a philandering British army captain known as John "Mad Jack" Byron.

His father, who squandered the family's money, died in France when George was three; his mother raised him in Aberdeen.

But when George's great-uncle died in 1798 he inherited both the title of Lord Byron and the ancestral family home, Newstead Abbey.

But when George's great-uncle died in 1798 he inherited both the title of Lord Byron and the ancestral family home, Newstead Abbey.

So there he lived in ruins that captured his young imagination.

Eventually he went to study at Cambridge University, where (among other things) he kept a pet bear, racked up massive debts, and (allegedly) fell in love with a choirboy.

After Cambridge? He went travelling.

Eventually he went to study at Cambridge University, where (among other things) he kept a pet bear, racked up massive debts, and (allegedly) fell in love with a choirboy.

After Cambridge? He went travelling.

The Grand Tour was a rite of passage for Englishmen at the time.

He travelled the Mediterranean and in 1810 fell in love with Greece, especially the people.

There, having already been writing verse for a few years, he started a long poem called Childe Harold's Pilgrimage.

He travelled the Mediterranean and in 1810 fell in love with Greece, especially the people.

There, having already been writing verse for a few years, he started a long poem called Childe Harold's Pilgrimage.

It tells the story of a young, melancholy traveller who has left a hedonistic life behind in search of something more.

When the first parts were published in 1812 it turned Byron into a celebrity, at home and abroad.

As he said, "I awoke one morning and found myself famous."

When the first parts were published in 1812 it turned Byron into a celebrity, at home and abroad.

As he said, "I awoke one morning and found myself famous."

Why was Byron so successful? Childe Harold was the right poem at the right time.

The Industrial Revolution was irreversibly changing society and destroying nature; hopes of a new, more liberal age set in motion by the French Revolution had come to nothing.

A time of despair.

The Industrial Revolution was irreversibly changing society and destroying nature; hopes of a new, more liberal age set in motion by the French Revolution had come to nothing.

A time of despair.

His literary reputation in Britain was mixed, but in continental Europe Byron was regarded as the world's greatest living poet, second only to Goethe.

In both cases his personal life fanned the flames lit by his poetry — artist and art were one, and the people loved it.

In both cases his personal life fanned the flames lit by his poetry — artist and art were one, and the people loved it.

Byron's poetry (and plays) for the next few years cemented his status as the living embodiment of Romanticism.

He lamented the coronation of Napoleon and wrote of flawed heroes, dark adventures, and restless melancholy — he had captured the zeitgeist.

He lamented the coronation of Napoleon and wrote of flawed heroes, dark adventures, and restless melancholy — he had captured the zeitgeist.

But Byron fled England in 1816, never to return.

Why? To escape the suffocating social pressure of his life there... and his creditors.

Because, athough Byron was Britain's best-selling poet, he had a habit of amassing huge debts and even had to sell his personal library.

Why? To escape the suffocating social pressure of his life there... and his creditors.

Because, athough Byron was Britain's best-selling poet, he had a habit of amassing huge debts and even had to sell his personal library.

And it was in the summer of 1816 that Byron met fellow poet Percy Shelley and his wife, Mary.

They spent a few days together during a storm by Lake Geneva, where to pass the time they told ghost stories — and Mary came up with the idea for what would become Frankenstein.

They spent a few days together during a storm by Lake Geneva, where to pass the time they told ghost stories — and Mary came up with the idea for what would become Frankenstein.

This was the same summer Byron visited Chillon Castle in Switzerland, which inspired one of his best poems, The Prisoner of Chillon.

He also left his mark, literally, by engraving his name into the walls of the dungeon.

In 1819 the final part of Childe Harold was published.

He also left his mark, literally, by engraving his name into the walls of the dungeon.

In 1819 the final part of Childe Harold was published.

Also in 1819 Percy and Mary Shelley moved to Italy; and Byron, apparently listless and going grey, had something of a regeneration.

He sold Newstead Abbey, thus paying off his debts, and helped Shelley with a newspaper called The Liberal, founded by their friend Leigh Hunt.

He sold Newstead Abbey, thus paying off his debts, and helped Shelley with a newspaper called The Liberal, founded by their friend Leigh Hunt.

It was during his Italian exile, among a slew of new affairs, that Byron started his epic, satirical poem Don Juan.

It tells the story of an accidental womaniser with a sort of witty, ironic realism.

This was totally different from Childe Harold — the real Byron shone through.

It tells the story of an accidental womaniser with a sort of witty, ironic realism.

This was totally different from Childe Harold — the real Byron shone through.

But in 1822, after a visit to see Byron, Percy Shelley drowned when sailing home off the coast of Italy; he was 29.

John Keats, the other great Romantic poet of their generation, had died a year earlier, aged just 25.

Was Byron doomed to face the same, untimely fate?

John Keats, the other great Romantic poet of their generation, had died a year earlier, aged just 25.

Was Byron doomed to face the same, untimely fate?

In April 1823, growing restless, Byron was convinced by pro-Greek British activists to join the Greek War of Independence against the Ottomans.

Byron had long written in support of Greece — as when he lamented the removal of the Parthenon Marbles, also called the Elgin Marbles.

Byron had long written in support of Greece — as when he lamented the removal of the Parthenon Marbles, also called the Elgin Marbles.

Byron poured all his remaining money into the cause, whether funding the refitting of fleets, paying soldiers, or covering debts.

He arrived there in July 1823, avoiding Ottoman forces along the way, and found himself plunged into an incredibly complex political situation.

He arrived there in July 1823, avoiding Ottoman forces along the way, and found himself plunged into an incredibly complex political situation.

So Byron both raised awareness for the Greek cause and supported it financially — but never saw its end.

He fell sick in Missolonghi and died on the 19th April, 200 years ago today, aged 36.

His body was repatriated and buried near his ancestral home in Nottinghamshire.

He fell sick in Missolonghi and died on the 19th April, 200 years ago today, aged 36.

His body was repatriated and buried near his ancestral home in Nottinghamshire.

The go-to word for Byron, at least in Britain, is scandalous. Why?

Some of the details missed in this brief biography include his litany of affairs, his (alleged) child by his half-sister Augusta Leigh, and his failed marriage (ending in separation) with Annabella Millbanke.

Some of the details missed in this brief biography include his litany of affairs, his (alleged) child by his half-sister Augusta Leigh, and his failed marriage (ending in separation) with Annabella Millbanke.

All these personal events — clashing with the morality of the time — were played out publicly.

This, alongside his feverish, international fame, is what made Lord Byron one of the world's first rock stars.

He inspired art and gossip, praise and disgust, in equal measure.

This, alongside his feverish, international fame, is what made Lord Byron one of the world's first rock stars.

He inspired art and gossip, praise and disgust, in equal measure.

But, above all, it was the version of Byron created by his semi-autobiographical Childe Harold that enthralled the imagination of Europe.

And yet, it seems, the real Byron was more of a witty ironist than the world-weary, brooding, Romantic hero he has come to typify.

And yet, it seems, the real Byron was more of a witty ironist than the world-weary, brooding, Romantic hero he has come to typify.

His contemporaries John Keats and Percy Shelley were better poets, but neither seemed to have the sheer life-force of Lord Byron.

He had a talent both for capturing the zeitgeist and, intentionally or not, making headline news with his tumultuous personal life.

He had a talent both for capturing the zeitgeist and, intentionally or not, making headline news with his tumultuous personal life.

So, even if his literary reputation is rather mixed, his status as a cultural icon is fixed.

A national hero in Greece, a Romantic prophet in continental Europe, and a scandalous, half-decent poet in Britain.

Statues of him litter cities around the world.

A national hero in Greece, a Romantic prophet in continental Europe, and a scandalous, half-decent poet in Britain.

Statues of him litter cities around the world.

How to summarise such a life?

Byron seemed to write his own, perfect epitaph in the closing stanzas of Childe Harold's Pilgrimage.

Light and dark, good and bad, scandal and success, tragedy and inspiration, indecency and heroism — all were one with Byron. Above all, he lived.

Byron seemed to write his own, perfect epitaph in the closing stanzas of Childe Harold's Pilgrimage.

Light and dark, good and bad, scandal and success, tragedy and inspiration, indecency and heroism — all were one with Byron. Above all, he lived.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh