In new study led by @bblarsen1 in collab w @veeslerlab @VUMC_Vaccines we map functional & antigenic landscape of Nipah virus receptor binding protein (RBP)

Results elucidate constraints on RBP function & provide insight re protein’s evolutionary potentialbiorxiv.org/content/10.110…

Results elucidate constraints on RBP function & provide insight re protein’s evolutionary potentialbiorxiv.org/content/10.110…

Nipah is bat virus that sporadically infects humans w high (~70%) fatality rate. Has been limited human transmission

Like other paramyxoviruses, Nipah uses two proteins to enter cells: RBP binds receptor & then triggers fusion (F) protein by process that is not fully understood

Like other paramyxoviruses, Nipah uses two proteins to enter cells: RBP binds receptor & then triggers fusion (F) protein by process that is not fully understood

RBP forms tetramer in which 4 constituent monomers (which are all identical in sequence) adopt 3 distinct conformations

RBP binds to two receptors, EFNB2 & EFNB3

RBP’s affinity for EFNB2 is very high (~0.1 nM, over an order of magnitude higher than SARSCoV2’s affinity for ACE2)

RBP binds to two receptors, EFNB2 & EFNB3

RBP’s affinity for EFNB2 is very high (~0.1 nM, over an order of magnitude higher than SARSCoV2’s affinity for ACE2)

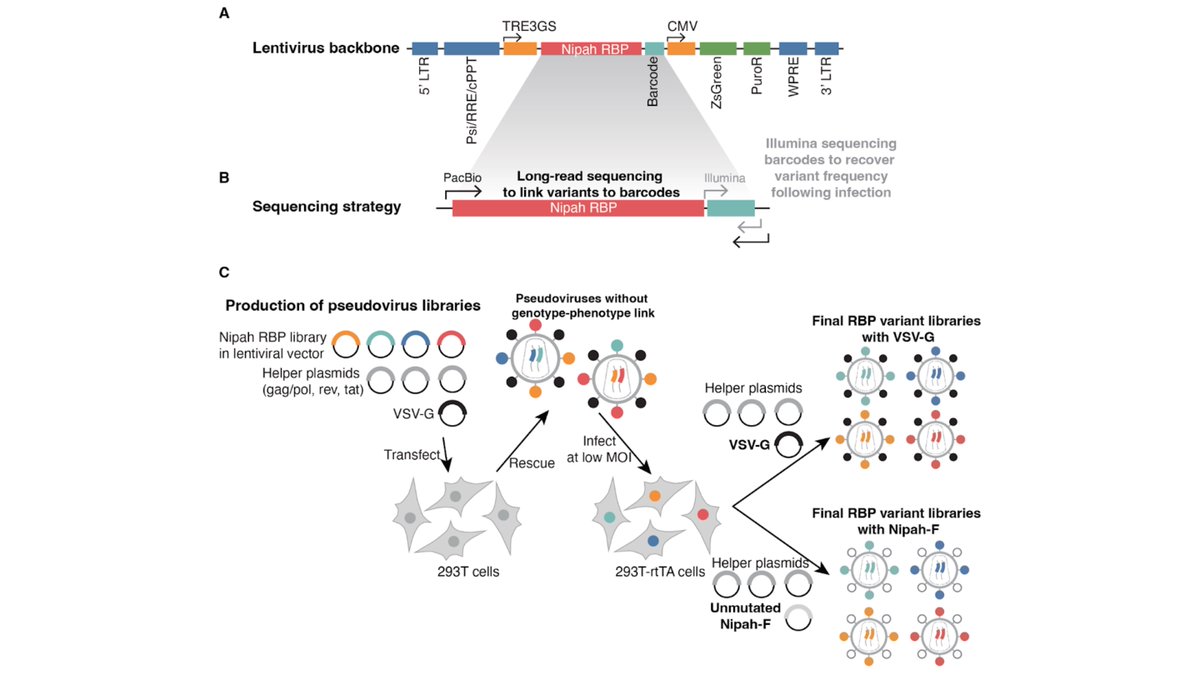

To study mutants of RBP, we used pseudovirus deep mutational scanning, which uses non-replicative lentivirions safe at BSL-2 ()

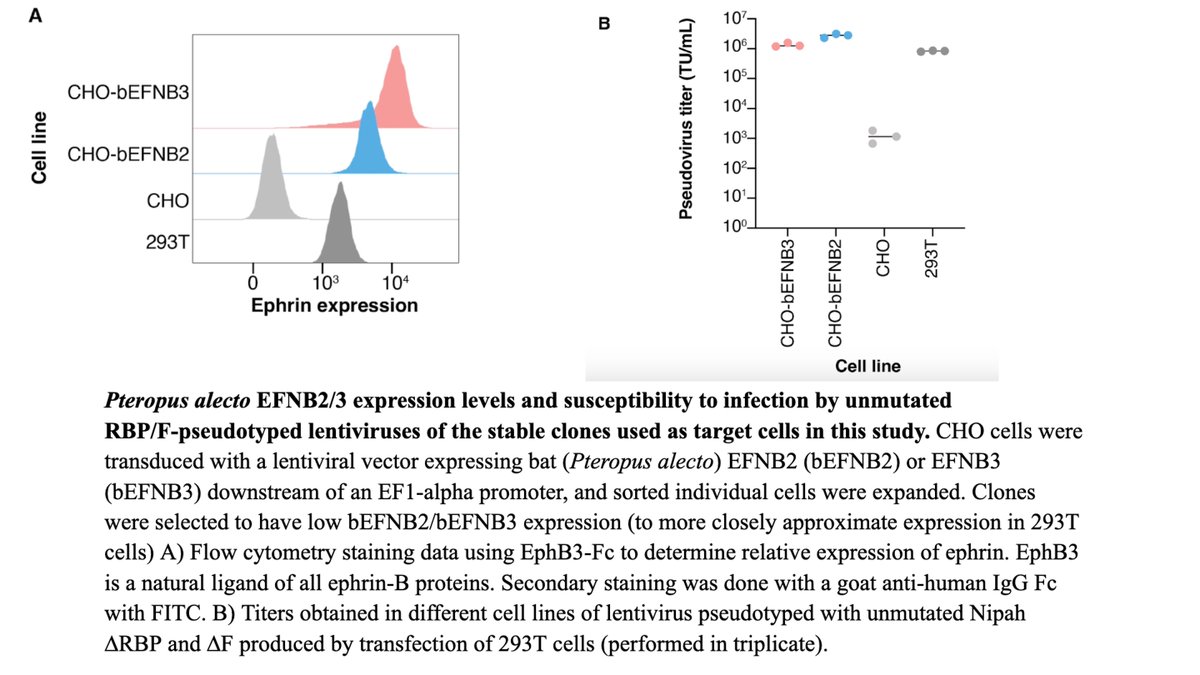

We generated pseudoviruses w all amino-acid mutants of RBP & quantified their ability to infect cells expressing EFNB2 or EFNB3 blog.addgene.org/viral-vectors-…

We generated pseudoviruses w all amino-acid mutants of RBP & quantified their ability to infect cells expressing EFNB2 or EFNB3 blog.addgene.org/viral-vectors-…

To ensure these safe pseudovirus experiments generated beneficial knowledge about RBP function & antigenicity but *not* potentially hazardous info () on mutations that adapt RBP to human receptors, we used cells expressing bat rather than human EFNs pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30419157/

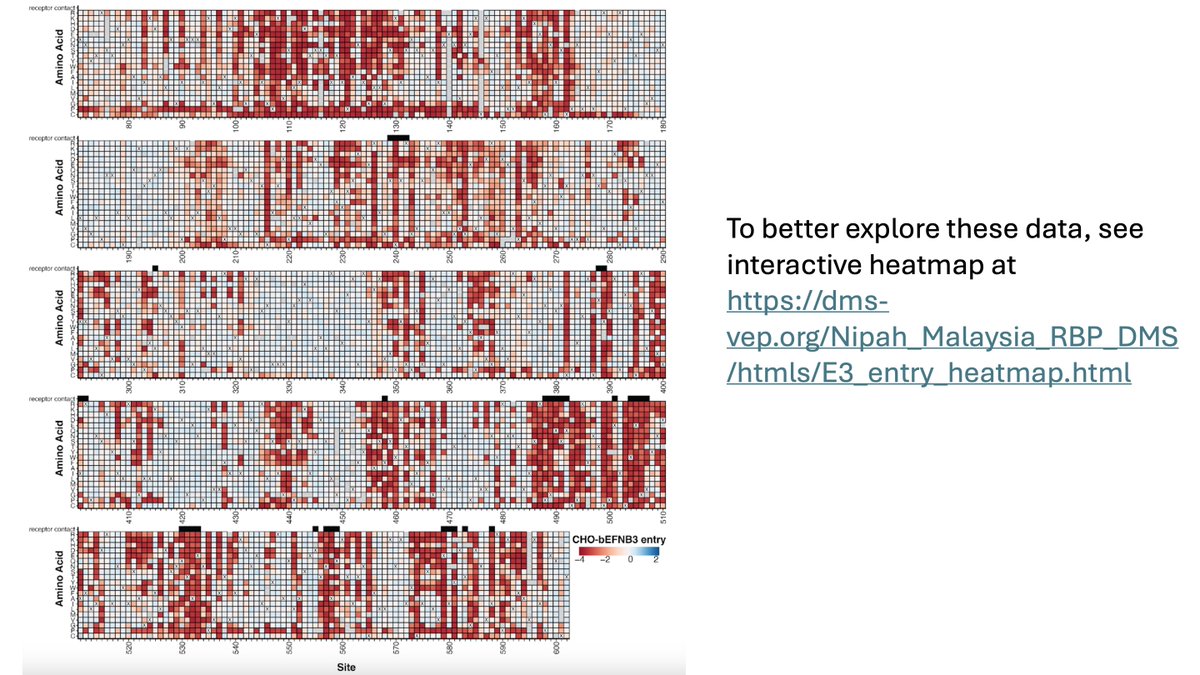

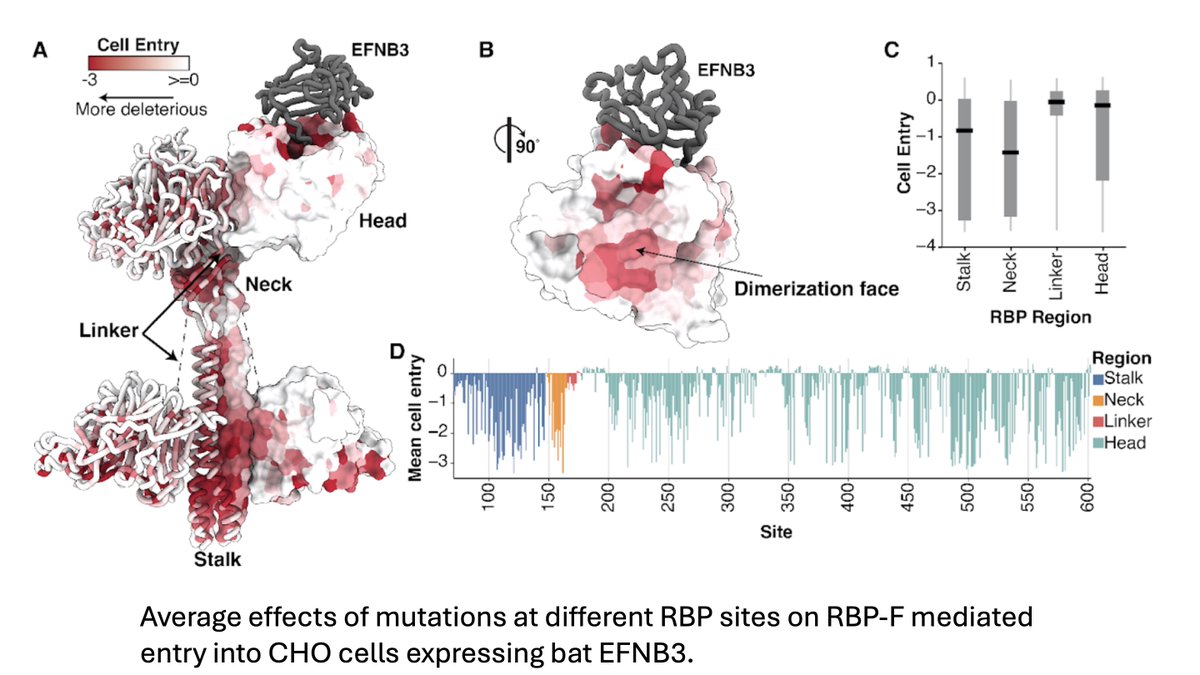

Figure below shows how all amino-acid mutations to RBP affect pseudovirus entry into cells expressing bat EFNB3.

(Best way to explore data is via interactive figure at ) dms-vep.org/Nipah_Malaysia…

(Best way to explore data is via interactive figure at ) dms-vep.org/Nipah_Malaysia…

Some regions of RBP quite tolerant of mutations, but others under heavy constraint (most mutations disrupt pseudovirus cell entry)

Constraint especially high in dimerization faces & sites in neck that likely play key role in triggering F (see paper for details on specific sites)

Constraint especially high in dimerization faces & sites in neck that likely play key role in triggering F (see paper for details on specific sites)

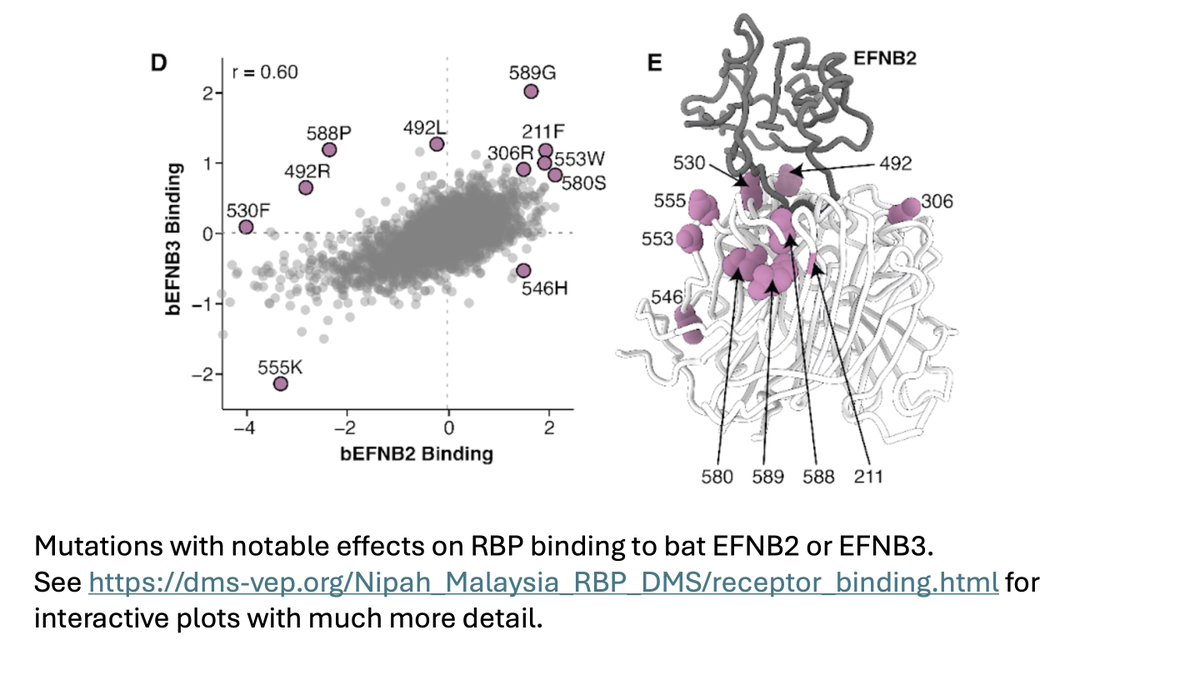

We also measured how all functionally tolerated RBP mutations affect binding to EFNB2 vs EFNB3, & identified specific mutations that increase binding to both or just one of the bat versions of these receptors

(See much more detail) dms-vep.org/Nipah_Malaysia…

(See much more detail) dms-vep.org/Nipah_Malaysia…

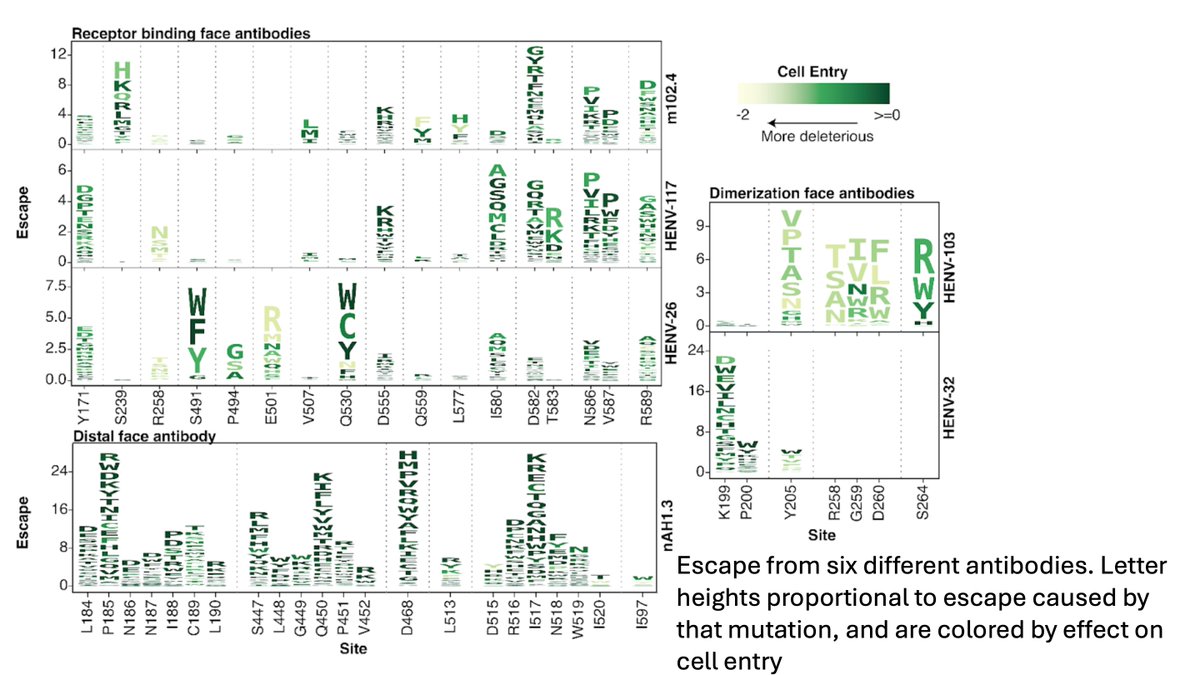

We also measured how all RBP mutations affect neutralization by panel of antibodies.

Some antibodies (eg, nAH1.3) are escaped by many well-tolerated mutations, whereas others (eg, HENV-103) are mostly escaped only by mutations that impair RBP function.

Some antibodies (eg, nAH1.3) are escaped by many well-tolerated mutations, whereas others (eg, HENV-103) are mostly escaped only by mutations that impair RBP function.

The above finding is informative for helping select antibodies that are likely to be resistant to viral escape. However, it is notable that antigenic diversity of known Nipah viruses is low, with almost none of the escape mutations observed among natural sequences.

Overall, this study generates a huge wealth of information for understanding RBP function, receptor binding, antigenicity, and evolution.

@bblarsen1 has made a superb webpage with interactive plots that facilitate exploration of the data: dms-vep.org/Nipah_Malaysia…

@bblarsen1 has made a superb webpage with interactive plots that facilitate exploration of the data: dms-vep.org/Nipah_Malaysia…

Thanks to everyone who contributed to this study: @bblarsen1, Teagan McMahon, Jack Brown, Zhaoqian Wang, @CaelanRadford, @VUMC_Vaccines, and @veeslerlab

The full pre-print is at: biorxiv.org/content/10.110…

The full pre-print is at: biorxiv.org/content/10.110…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh