Among the most promising military applications of AI is staff work. Tons of routine products—intel summaries, orders, etc.—can be generated much faster by machine. Does this mean staffs will reverse the historic trend and begin to shrink?

No: they’re about to explode in size.🧵

No: they’re about to explode in size.🧵

In the Napoleonic era, a divisional or corps staff was never more than a dozen soldiers, whereas today it’s pushing toward a thousand for formations of about the same size. Part of a general trend in tooth-to-tail ratios.

The reasons are fairly obvious: modern armies are more complicated, requiring more logistical coordination, fire control, etc.

BUT. There’s a subtler effect at play too: Jevon’s paradox. Simply stated, the more efficiently a resource can be used, the greater the demand.

BUT. There’s a subtler effect at play too: Jevon’s paradox. Simply stated, the more efficiently a resource can be used, the greater the demand.

It’s the story of Eli Whitney and the cotton gin. He thought he could reduce the demand for slavery by creating a labor-saving device for processing cotton. But by increasing the cotton each slave produced, he made them much, much more valuable.

Same story with staff work. The more valuable data/products/whatever that each staff member can generate, the greater the demand.

The typewriter, for instance, did not reduce the number of clerks (secretaries); it greatly increased the volume of correspondence.

The typewriter, for instance, did not reduce the number of clerks (secretaries); it greatly increased the volume of correspondence.

This came at a convenient time, when more information needed to be sent over greater distances. But typewriters also *enabled* more complex operations, requiring more detailed orders, greater coordination, etc., and thereby fueling demand for larger staffs.

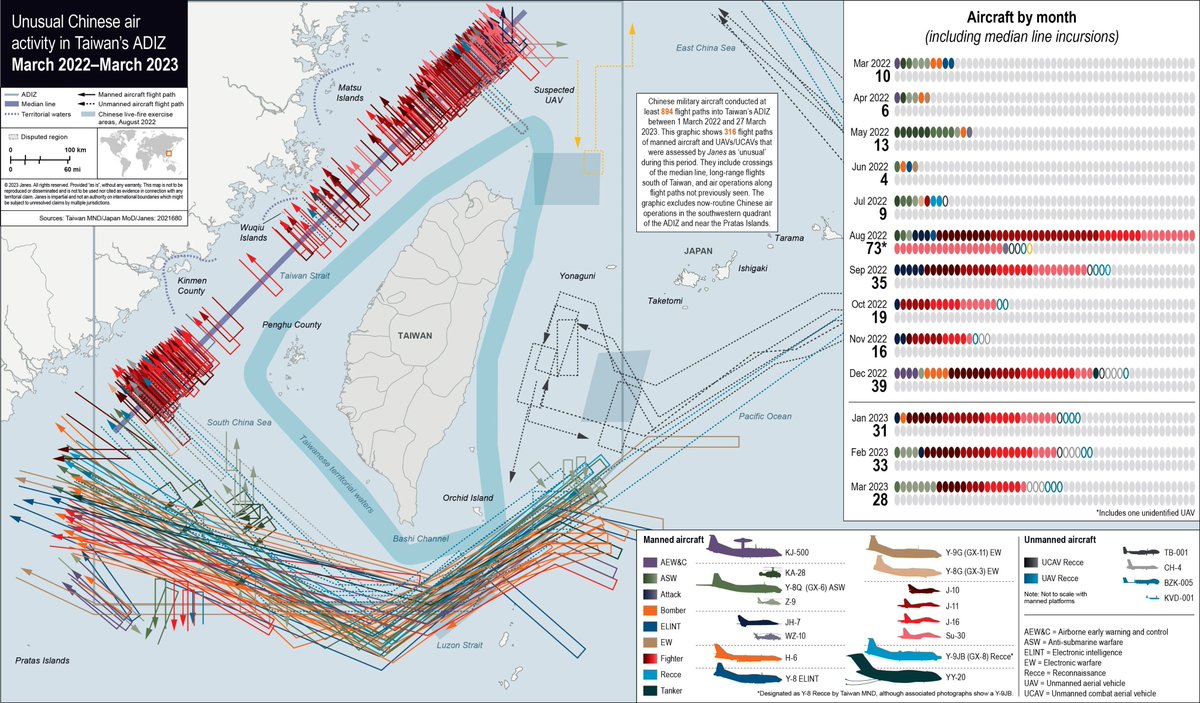

As an example, consider the situational awareness that persistent surveillance gives HQ—often better than the ground troops. Pair it with AI for threat ID, predictive firing solutions, etc., and you have several staff members micromanaging a single squad.

https://twitter.com/bazaarofwar/status/1651619485923659777

(This would also completely alter chain-of-command structure, but that’s another story. For more on that, see: )dispatch.bazaarofwar.com/p/drones-trenc…

This is just one example, and not an especially good one—the entire point is that it’s hard to predict new uses for technology until its available in abundance. The one certainty is that that abundance will only grow demand, not shrink it.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh