From the Byzantines to Brutalism, here's a brief introduction to the architecture of Eastern Europe:

The architectural history of Eastern Europe is fascinating — and differs greatly from Western Europe.

It is also ancient: the oldest gold treasure in the world was discovered in Bulgaria, a country which is also home to the ancient tombs of the kings of Thrace:

It is also ancient: the oldest gold treasure in the world was discovered in Bulgaria, a country which is also home to the ancient tombs of the kings of Thrace:

The Greeks and Macedonians, and after them the Romans, dominated what we now loosely call Eastern Europe.

Thus some of the best-preserved classical architecture is found there — like the colossal Pula Arena in Croatia, built during the reign of Augustus over 2,000 years ago:

Thus some of the best-preserved classical architecture is found there — like the colossal Pula Arena in Croatia, built during the reign of Augustus over 2,000 years ago:

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire it was Carolingian, Romanesque, and finally Gothic architecture that flourished in western Europe.

But in eastern Europe it was the Byzantine Empire that held sway — with their domes, semi-domes, round arches, mosaics, and icons:

But in eastern Europe it was the Byzantine Empire that held sway — with their domes, semi-domes, round arches, mosaics, and icons:

From this Byzantine heritage regional forms of architecture emerged during the Middle Ages in modern-day countries like Bulgaria, Ukraine, Serbia, Romania, and Belarus.

In all cases they were totally different from the religious architecture of western Europe at the same time:

In all cases they were totally different from the religious architecture of western Europe at the same time:

Then, in the 14th century, the Ottomans burst onto the scene.

They swept through Turkey, defeated the Byzantine Empire, and proceeded to conquer vast swathes of the Balkans and Eastern Europe.

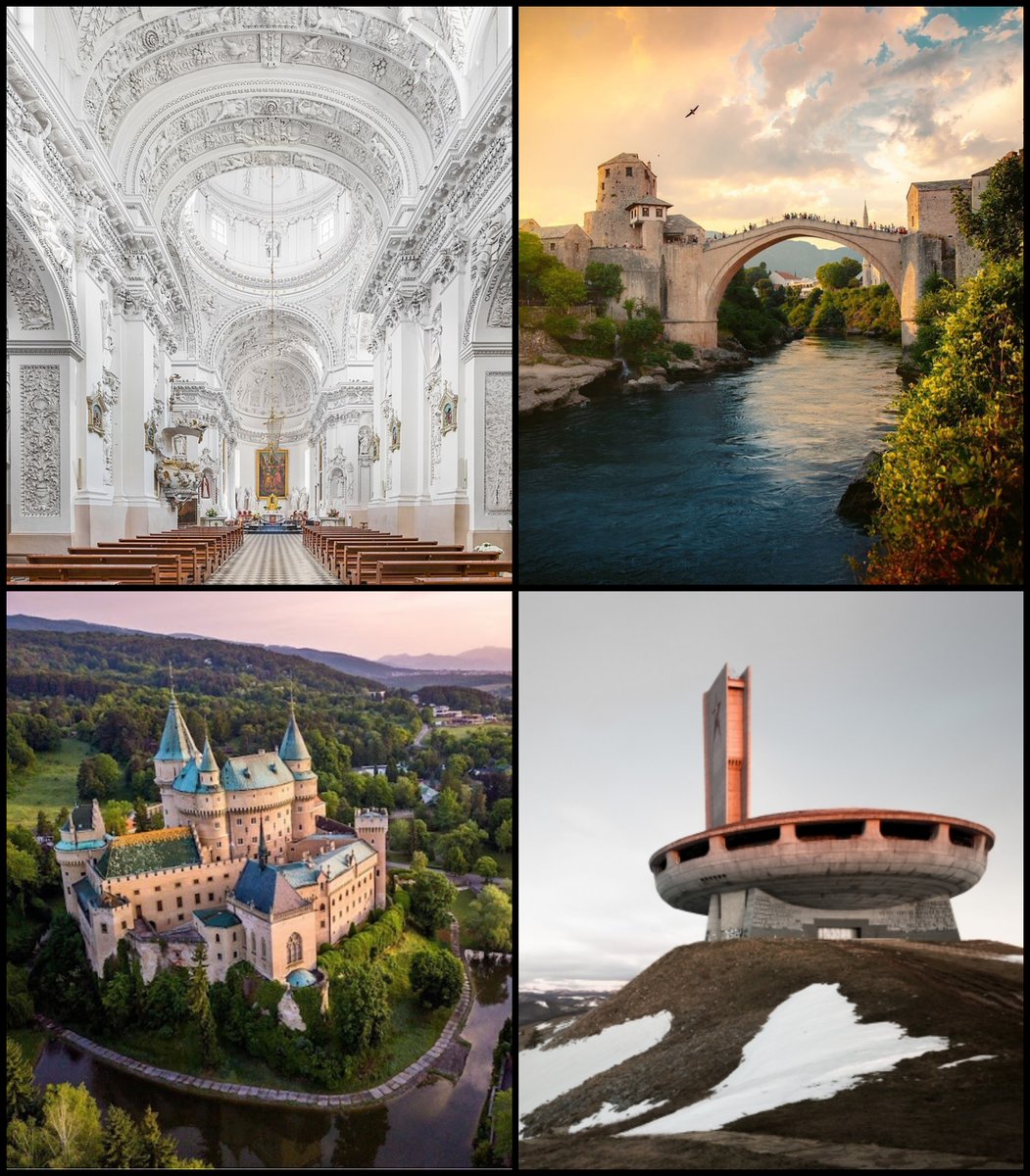

Their most famous legacy here is perhaps the Mostar Bridge in Bosnia and Herzegovina:

They swept through Turkey, defeated the Byzantine Empire, and proceeded to conquer vast swathes of the Balkans and Eastern Europe.

Their most famous legacy here is perhaps the Mostar Bridge in Bosnia and Herzegovina:

But Ottoman Architecture left a much broader, lasting influence on parts of Eastern Europe.

Ottoman mosques are scattered around the Balkans, for example, usually with their distinctive domes, such as the 17th century Sinan Pasha Mosque in Prizren, Kosovo:

Ottoman mosques are scattered around the Balkans, for example, usually with their distinctive domes, such as the 17th century Sinan Pasha Mosque in Prizren, Kosovo:

Still, the Ottoman Empire only ruled in the Balkans.

In other parts of Central and Eastern Europe there were different architectural forces at work.

In Prague, for example, the fabulous Vladislav Hall is a perfect example of Bohemian Gothic architecture:

In other parts of Central and Eastern Europe there were different architectural forces at work.

In Prague, for example, the fabulous Vladislav Hall is a perfect example of Bohemian Gothic architecture:

In Russia, meanwhile, incredibly distinctive forms of religious architecture emerged, in no case more famously than that of St Basil's Cathedral, built during the 16th century:

And in Armenia a totally unique form of architecture had emerged during the Middle Ages, defined by conical spires raised on slender barrels, often built in isolated locations.

Like the fantastical Tatev Monastery:

Like the fantastical Tatev Monastery:

Another rather unusual subgenre of Gothic Architecture also emerged in Northern, Central, and Northeastern Europe.

It was called "Brick Gothic", for obvious reasons, and the Church of St Anne in Vilnius is one of its best examples:

It was called "Brick Gothic", for obvious reasons, and the Church of St Anne in Vilnius is one of its best examples:

Baroque Architecture also became popular in parts of Eastern Europe, especially the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

The unique Church of St. Peter and St. Paul in Vilnius, built at the beginning of the 18th century, is covered in thousands of pure white stucco decorations:

The unique Church of St. Peter and St. Paul in Vilnius, built at the beginning of the 18th century, is covered in thousands of pure white stucco decorations:

During the 19th century, as the Ottoman Empire began to fade and Balkan nations achieved independence, there was a revival of Byzantine architecture.

Perhaps the best example of this Neo-Byzantine phase is Alexander Nevsky Cathedral in Sofia, built between the 1880s and 1920s:

Perhaps the best example of this Neo-Byzantine phase is Alexander Nevsky Cathedral in Sofia, built between the 1880s and 1920s:

The broader Gothic Revival taking place across Europe also bore fruit in Central and Eastern Europe — as with the Hungarian Parliament in Budapest, opened in 1902.

A sort of Gothic fantasy palace.

A sort of Gothic fantasy palace.

Other western European architectural movements also had a major influence in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, whether Austro-Hungarian Eclecticism, French Beaux-Arts, or Art Nouveau.

Consider the Athenaeum, a neoclassical concert hall in Bucharest, from 1888:

Consider the Athenaeum, a neoclassical concert hall in Bucharest, from 1888:

Or the House with Chimaeras in Kyiv, built at the beginning of the 1900s.

It represents a wildly unusual, imaginative interpretation of Art Nouveau — this house is covered in dozens of creatures, some real and some fictional, some friendly and some nightmarish:

It represents a wildly unusual, imaginative interpretation of Art Nouveau — this house is covered in dozens of creatures, some real and some fictional, some friendly and some nightmarish:

But things soon changed — and diverged once again from Western Europe — with the rise of the USSR.

Although Soviet architecture is usually stereotyped as Brutalist, in the 1940s and 1950s it was something else entirely; just consider Warsaw's Palace of Culture and Science:

Although Soviet architecture is usually stereotyped as Brutalist, in the 1940s and 1950s it was something else entirely; just consider Warsaw's Palace of Culture and Science:

In was in the 1970s and 1980s that Communist nations turned to Brutalism.

The former Bank of Georgia in Tblisi, the Slovak Radio Building in Bratislava, or the Buzluzhda Monument in Bulgaria — colossal concrete monoliths, still futuristic even decades later.

The former Bank of Georgia in Tblisi, the Slovak Radio Building in Bratislava, or the Buzluzhda Monument in Bulgaria — colossal concrete monoliths, still futuristic even decades later.

Nor to forget the vernacular architecture of Eastern Europe.

Poland, for example, is home to a number of Late Medieval and Early Renaissance churches built in a highly distinctive style — and wholly from wood:

Poland, for example, is home to a number of Late Medieval and Early Renaissance churches built in a highly distinctive style — and wholly from wood:

And then there is something like the Old Town of Plovdiv in Bulgaria, where woven among 3,000 year-old Thracian ruins are steets lined with traditional, jettied houses painted in bright colours:

Since the 1990s plenty of Postmodern Architecture has also been built in Central and Eastern Europe, such as the playful "Dancing House" in Prague:

There have also been some notable examples of revived traditional architecture in Eastern Europe, built with the help of modern methods and materials.

Like Saint Sava in Belgrade, a vast Neo-Byzantine church opened in 2004 — with a reinforced concrete dome.

Like Saint Sava in Belgrade, a vast Neo-Byzantine church opened in 2004 — with a reinforced concrete dome.

And that is a very brief, highly condensed history of architecture in Eastern Europe.

A complex legacy which has created some of the world's most interesting cities, where every street is a palimpsest of thousand of years of wildly varying influences, styles, and cultures.

A complex legacy which has created some of the world's most interesting cities, where every street is a palimpsest of thousand of years of wildly varying influences, styles, and cultures.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh