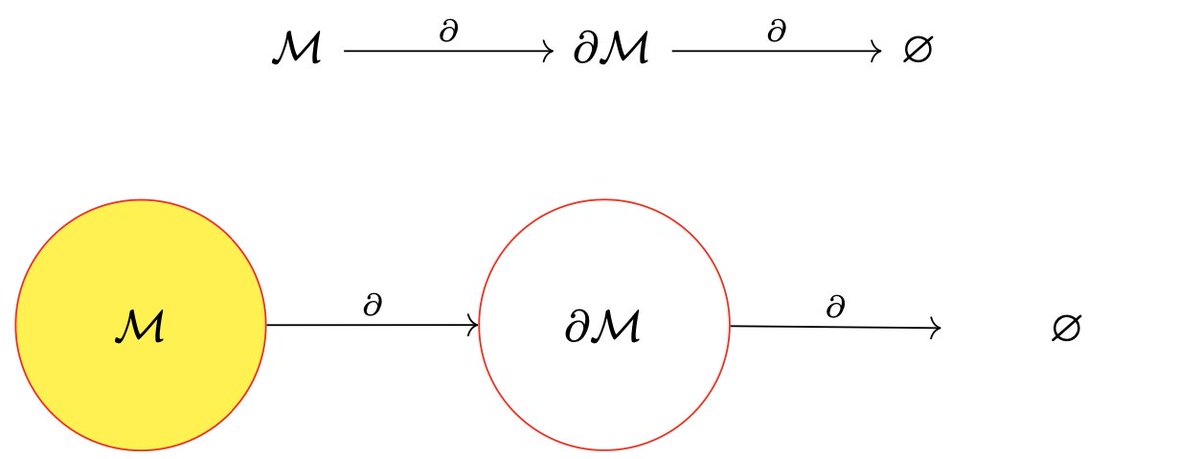

"The boundary of a boundary is always empty."

A huge amount of (classical) physics, including much of general relativity and electromagnetism, can be deduced directly from this simple mathematical fact.

Yet, on the surface, it doesn't seem to have much to do with physics. (1/10)

A huge amount of (classical) physics, including much of general relativity and electromagnetism, can be deduced directly from this simple mathematical fact.

Yet, on the surface, it doesn't seem to have much to do with physics. (1/10)

Some spaces (like spheres) don't have boundaries. But, when the boundary exists, it's always one dimension lower (codimension-1). A disc is a 2-dimensional space, but its boundary is a 1-dimensional circle.

But what's the boundary of a circle? Well, it doesn't have one. (2/10)

But what's the boundary of a circle? Well, it doesn't have one. (2/10)

It turns out that this will always be true, for purely topological reasons: a space may or may not have a boundary, but its boundary never will.

Yet physics is about differential equations, not topology, right? So how can this fact have any relevance to physics? (3/10)

Yet physics is about differential equations, not topology, right? So how can this fact have any relevance to physics? (3/10)

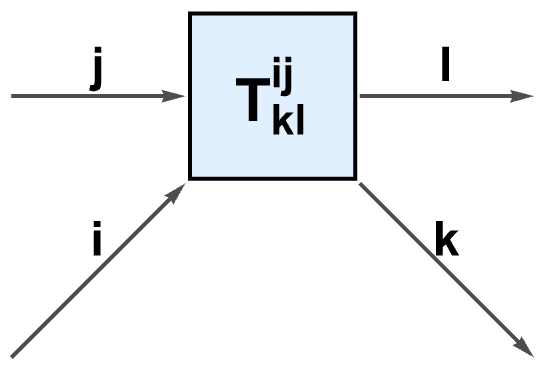

Well, the boundary operator, which maps a space to its boundary space, acts formally very much like a derivative (obeys the product rule, etc.). This is no coincidence: the boundary operator on submanifolds is dual to the exterior derivative operator on differential forms. (4/10)

This allows us to translate topological statements about boundaries into analytic statements about exterior derivatives. So our "boundary of a boundary is empty" statement now becomes a statement about symmetries of the covariant derivative operator on certain tensors. (5/10)

When applied to the Riemann tensor and then contracted, it yields the contracted Bianchi identities: the statement that the covariant divergence of the Einstein tensor vanishes. But, in GR, the Einstein tensor is equal to the stress-energy tensor (times a constant). (6/10)

So the covariant divergence of stress-energy vanishes - in physical terms, this means that energy and momentum are always conserved in relativity!

If instead we apply the Bianchi identities to the electromagnetic field tensor, we obtain the (homogeneous) Maxwell equations. (7/10)

If instead we apply the Bianchi identities to the electromagnetic field tensor, we obtain the (homogeneous) Maxwell equations. (7/10)

These encompass both Gauss' law for magnetism and the Maxwell-Faraday law of induction.

In fact, under the gravitoelectromagnetic formalism, the entirety of general relativity can be represented in this way. Just start by choosing a unit timelike vector field... (8/10)

In fact, under the gravitoelectromagnetic formalism, the entirety of general relativity can be represented in this way. Just start by choosing a unit timelike vector field... (8/10)

This field allows us to decompose the Riemann/Weyl tensors into electrogravitic and magnetogravitic tensors (via the Bel decomposition), formally analogous to electric and magnetic field vectors. And, just as for Maxwell, the Bianchi identities give us the dynamical laws. (9/10)

Within this formalism, the full system of Einstein equations emerge as rank-2 tensorial analogs of the rank-1 (vector) Maxwell equations. Yet, somehow, it all goes back to boundaries of boundaries, and their emptiness... (10/10)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh