126 years ago today the most stylish painter in history was born.

She was called Tamara de Lempicka and everything about her life and art embodied the spirit of the 1920s.

If you like Art Deco, you'll love Tamara de Lempicka...

She was called Tamara de Lempicka and everything about her life and art embodied the spirit of the 1920s.

If you like Art Deco, you'll love Tamara de Lempicka...

Tamara Gurwik-Górska was born on 16th May 1898 in Warsaw, Poland. Her father was a lawyer and her mother a socialite.

Her rebelliousness was clear from the start — at the age of ten, dissatisified with the work of a family portraitist, she redid it herself.

As she later said:

Her rebelliousness was clear from the start — at the age of ten, dissatisified with the work of a family portraitist, she redid it herself.

As she later said:

After dropping out of her Swiss boarding school she travelled to St Petersburg and married a lawyer, Tadeusz Łempicki.

But everything changed with the Russian Revolution of 1917.

She managed to get Tadeusz, who had been arrested, out of prison — the family then fled to Paris.

But everything changed with the Russian Revolution of 1917.

She managed to get Tadeusz, who had been arrested, out of prison — the family then fled to Paris.

Lempicka was just twenty, the mother of a young child, and her husband was jobless... so she decided to become a painter.

Lempicka studied at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, where she came under the influence of modernists like Maurice Denis and Andre Lhote.

Lempicka studied at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, where she came under the influence of modernists like Maurice Denis and Andre Lhote.

Lempicka flourished in 1920s Paris, becoming a popular hostess and engaging in scandalous affairs with both men and women — she was a social star.

It was a whirlpool of modernism and opulence, of the avant-garde and of reckless epicureanism, all in the lingering shadow of WWI.

It was a whirlpool of modernism and opulence, of the avant-garde and of reckless epicureanism, all in the lingering shadow of WWI.

Lempicka's early work, influenced primarily by Lhote, was exhibited in Paris' art salons.

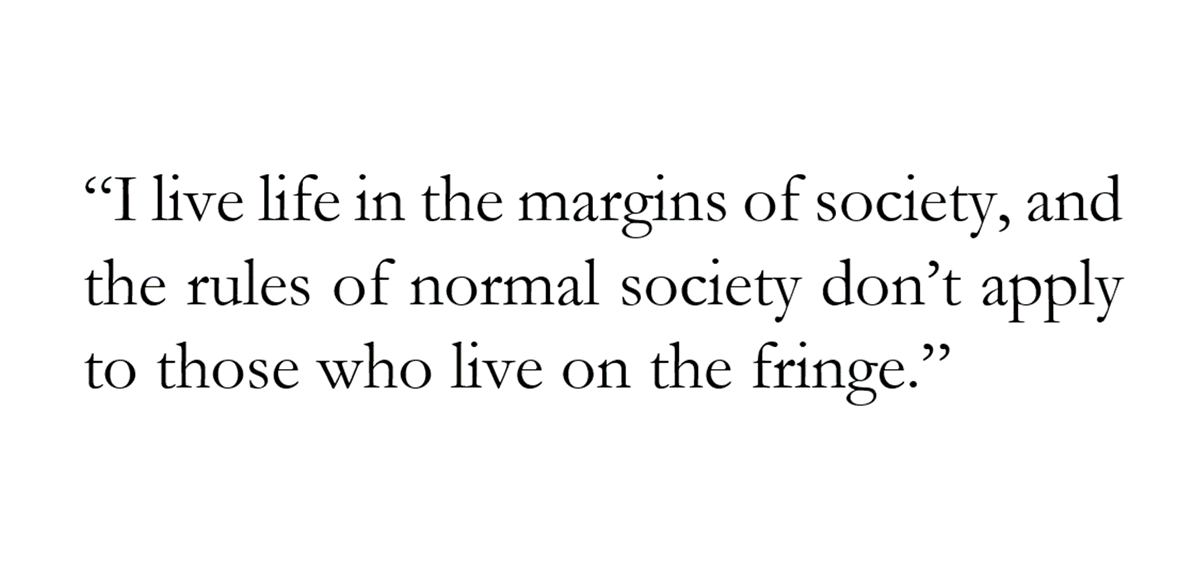

From the Kiss (left, 1922) to the Green Veil (right, 1924) you can see her style maturing — from loose brushwork and darker tones to smooth forms and vivid colours.

From the Kiss (left, 1922) to the Green Veil (right, 1924) you can see her style maturing — from loose brushwork and darker tones to smooth forms and vivid colours.

Suitably, it was at the 1925 "Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs" in Paris — which gave Art Deco its name — that Lempicka established her artistic reputation.

She had forged a distinctive style that captured the prevailing spirit of the 1920s.

She had forged a distinctive style that captured the prevailing spirit of the 1920s.

The striking thing about Lempicka's personal brand of Cubism was its classical influence.

Many Post-Impressionist, Cubist, and Modernist painters had done away with traditional modelling and perspective.

Their paintings increasingly lacked depth and used flat planes of colour.

Many Post-Impressionist, Cubist, and Modernist painters had done away with traditional modelling and perspective.

Their paintings increasingly lacked depth and used flat planes of colour.

Not Lempicka.

Although she employed the quasi-abstract shapes of the Cubists, she combined them with real depth and with stylised poses inspired by Renaissance artists like Raphael and Botticelli

It's like Cubism come to life, as if Lempicka had reassembled a work by Picasso.

Although she employed the quasi-abstract shapes of the Cubists, she combined them with real depth and with stylised poses inspired by Renaissance artists like Raphael and Botticelli

It's like Cubism come to life, as if Lempicka had reassembled a work by Picasso.

It was in her portraits that Lempicka's fusion of the modern and the traditional — like Art Deco itself — shines brightest.

They are, collectively, a remarkable artistic achievement, and one that seemingly conveys the cultural ideals of the entire era.

A 1920s Raphael.

They are, collectively, a remarkable artistic achievement, and one that seemingly conveys the cultural ideals of the entire era.

A 1920s Raphael.

Lempicka's portraits are also startlingly futuristic, mixing Art Deco's lavishness with the technological hopes and fears of the day.

She gave everything a smooth, metallic texture, so that her humans look like robots.

Even her Botticelli curls have a machine-like gleam.

She gave everything a smooth, metallic texture, so that her humans look like robots.

Even her Botticelli curls have a machine-like gleam.

The cityscapes that haunt the backgrounds of Lempicka's portraits are reminiscent of Fritz Lang's 1927 Art Deco-science fiction masterpiece, Metropolis.

Those soaring-silver skyscrapers are almost terrifying in their monumentality — the looming, mechanical towers of a new world.

Those soaring-silver skyscrapers are almost terrifying in their monumentality — the looming, mechanical towers of a new world.

Lempicka had earned herself a clientele of Paris' richest and most famous socialities, whether aristocrats or artists, and she painted them again and again in her unique way.

Her studio even became something of a Parisian landmark; these were days of celebrity and success.

Her studio even became something of a Parisian landmark; these were days of celebrity and success.

Lempicka's portrait of Marjorie Ferry might be her best.

The glamour and decadence we associate with the 1920s, the avant-garde art and the strange mixture of disillusionment with optimism, of heedless extravagance with looming catastrophe... it's all there.

The glamour and decadence we associate with the 1920s, the avant-garde art and the strange mixture of disillusionment with optimism, of heedless extravagance with looming catastrophe... it's all there.

The famous Autoportrait in a Green Bugatti, commissioned by the German magazine Die Dame in 1928, was one of many paintings by Lempicka featured in print.

By 1930 she had become an internationally famous artist with exhibitions all around Europe and America.

By 1930 she had become an internationally famous artist with exhibitions all around Europe and America.

But Lempicka's fame was, like Art Deco itself, short-lived.

Still, by 1934 she had divorced Tadeusz and married Baron Raoul Kuffner — all seemed well.

But the Great Depression and the rise of political tensions in Europe were fundamentally changing both society and art.

Still, by 1934 she had divorced Tadeusz and married Baron Raoul Kuffner — all seemed well.

But the Great Depression and the rise of political tensions in Europe were fundamentally changing both society and art.

As the 1930s wore on Lempicka seemed to experience something of a spiritual crisis; her fame was starting to wane and the cultural winds were shifting.

Religious themes dominated her work in this period, as in The Madonna with a Tear, from 1935:

Religious themes dominated her work in this period, as in The Madonna with a Tear, from 1935:

Gone was the luxury of Art Deco and the decadence of the Roaring Twenties.

Lempicka had turned her hand to much more sober subject matters.

And yet, more than ever before, her art had real, sincere emotional expressiveness.

Lempicka had turned her hand to much more sober subject matters.

And yet, more than ever before, her art had real, sincere emotional expressiveness.

In 1939, after the outbreak of the Second World War, Lempicka and her husband fled to America.

She had been there before and was well-known; a career surely awaited.

Her most striking painting from this time is Escape (1939), which needs no explanation.

She had been there before and was well-known; a career surely awaited.

Her most striking painting from this time is Escape (1939), which needs no explanation.

But things did not go as planned.

See, Lempicka's formerly hyper-modern style had become old-fashioned.

With exhibitions unsuccessful and portrait commisions declining, she struggled to find direction, even turning to still lifes:

See, Lempicka's formerly hyper-modern style had become old-fashioned.

With exhibitions unsuccessful and portrait commisions declining, she struggled to find direction, even turning to still lifes:

In the 1950s and 60s, perhaps inspired by the Abstract Expressionism of postwar New York, embodied in painters like Jackson Pollock, Lempicka dived into abstract art.

She had cast off her beloved Parisian style in an effort to keep up with the times.

She had cast off her beloved Parisian style in an effort to keep up with the times.

But by the late 1960s it was clear her career had stalled, with the sumptuous futurism of Art Deco long-buried by austere modernism — the real Lempicka had no place in this new artistic world.

She returned to religious themes; her last painting, in 1974, was of St Anthony:

She returned to religious themes; her last painting, in 1974, was of St Anthony:

In 1972 a Paris exhibition saw the "rediscovery" of Art Deco and a renewed interest in Lempicka — but she had already retired.

In 1974 she moved to Mexico, where she died six years later, her ashes scattered over Popocatépetl.

The end of a long, complex, wildly colourful life.

In 1974 she moved to Mexico, where she died six years later, her ashes scattered over Popocatépetl.

The end of a long, complex, wildly colourful life.

And here is Tamara de Lempicka herself, born 126 years ago today.

Few painters have captured the feeling of their age like Lempicka, whose art seems to contain a piece of the soul of the 1920s.

Yet, as with all great art, it has exceeded its context — and become timeless.

Few painters have captured the feeling of their age like Lempicka, whose art seems to contain a piece of the soul of the 1920s.

Yet, as with all great art, it has exceeded its context — and become timeless.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh