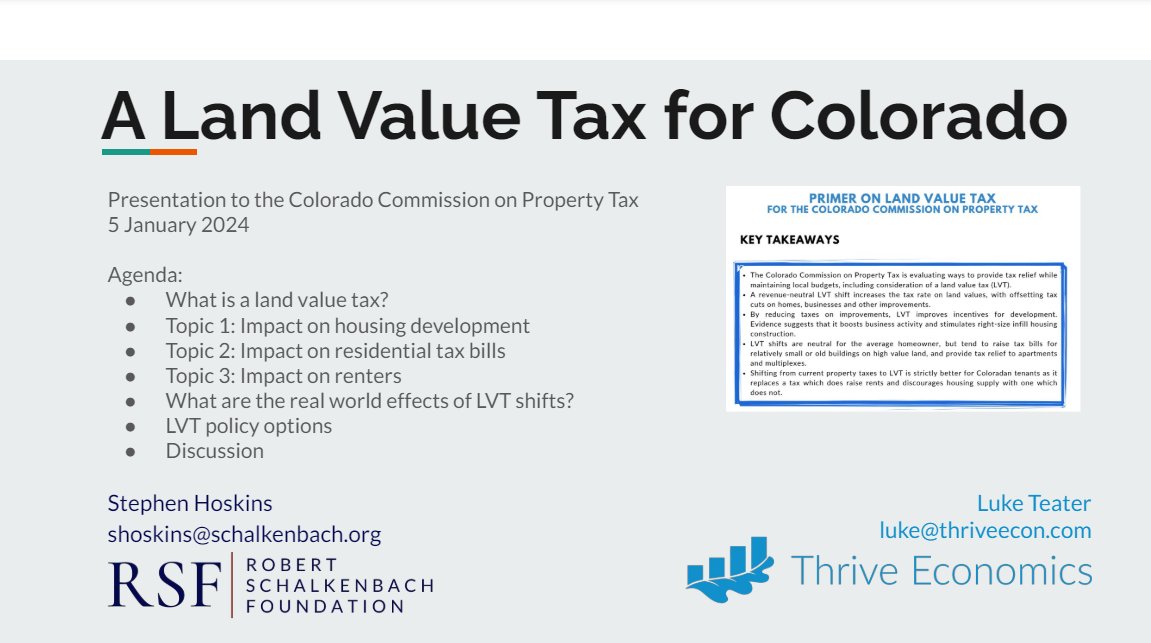

🔰 Here's the basic case for turning property taxes into a land value tax (LVT), as presented to the Colorado Commission on Property Tax back in January 🧵

LVT shifts:

🔰 boost business activity & construction of multifamily housing

🔰 are neutral for the typical homeowner, tend to increase tax bills on vacant/underutilized land, provide tax relief for multifamily housing

🔰 are strictly better for tenants as a tax which does raise rents is replaced by one which does not.

leg.colorado.gov/sites/default/…

LVT shifts:

🔰 boost business activity & construction of multifamily housing

🔰 are neutral for the typical homeowner, tend to increase tax bills on vacant/underutilized land, provide tax relief for multifamily housing

🔰 are strictly better for tenants as a tax which does raise rents is replaced by one which does not.

leg.colorado.gov/sites/default/…

🔰 What is a land value tax? 🔰

* LVT is a recurring tax charged to property owners in proportion to the value of the land they own (which includes its location value).

* LVT shifts involve a revenue-neutral increase in LVT used to fund tax cuts for homes & other buildings.

* LVT is a recurring tax charged to property owners in proportion to the value of the land they own (which includes its location value).

* LVT shifts involve a revenue-neutral increase in LVT used to fund tax cuts for homes & other buildings.

(If you want more detail about how an LVT shift works in practice, see here:

)schalkenbach.org/how-does-a-lan…

)schalkenbach.org/how-does-a-lan…

🔰 What is the impact of a LVT shift on housing? 🔰

* As the old saying goes "if you want less of something, tax it"

* Traditional property taxes penalize development by taxing the new buildings.

* Not so for an LVT shift, which rewards construction.

(Data on this below)

* As the old saying goes "if you want less of something, tax it"

* Traditional property taxes penalize development by taxing the new buildings.

* Not so for an LVT shift, which rewards construction.

(Data on this below)

🔰 What is the impact of a LVT shift on tax bills? 🔰

It depends

Rule-of-thumb: calculate a property's Intensity Ratio (IR) by taking Improvement Value divided by Total Value

⬇️ Properties with an above-average IR get a tax cut from an LVT shift

⬆️ Below-average IRs pay more

It depends

Rule-of-thumb: calculate a property's Intensity Ratio (IR) by taking Improvement Value divided by Total Value

⬇️ Properties with an above-average IR get a tax cut from an LVT shift

⬆️ Below-average IRs pay more

The upshot of the above is that typically LVT shifts cause tax bills to:

⬆️ for vacant land/car parks

⬆️ for industrial uses

⬇️ for multifamily housing

⬇️ for commercial buildings

⬇️/⬆️ have a range of effects for single family homes (depending on the intensity ratio):

⬆️ for vacant land/car parks

⬆️ for industrial uses

⬇️ for multifamily housing

⬇️ for commercial buildings

⬇️/⬆️ have a range of effects for single family homes (depending on the intensity ratio):

🔰 What is the impact of LVT on rents? 🔰

Answer: Unlike taxes on buildings, land taxes do not get passed on to tenants. Full explanation in the QT.

Shifting the tax base from improvements to land will increase housing supply and reduce rents.

Answer: Unlike taxes on buildings, land taxes do not get passed on to tenants. Full explanation in the QT.

Shifting the tax base from improvements to land will increase housing supply and reduce rents.

https://x.com/GeorgistSteve/status/1671584959168135171

🔰 Okay but what evidence do you have about the real-world effects of LVT? 🔰

In Pennsylvania it expanded entrepreneurship, rewarded renovations & boosted building (especially multifamily).

A recent US-wide study finds the same:

schalkenbach.org/wp-content/upl…

In Pennsylvania it expanded entrepreneurship, rewarded renovations & boosted building (especially multifamily).

A recent US-wide study finds the same:

schalkenbach.org/wp-content/upl…

https://x.com/GeorgistSteve/status/1738351402588729389

🔰Is LVT supported by economists? 🔰

Answer: Yes! From across the political spectrum!

Back in 1990, 30 econ profs urged Gorbachev to tax land: ()

A recent poll of economists found strong support for Detroit's LVT:

en.wikisource.org/wiki/Open_lett…

Answer: Yes! From across the political spectrum!

Back in 1990, 30 econ profs urged Gorbachev to tax land: ()

A recent poll of economists found strong support for Detroit's LVT:

en.wikisource.org/wiki/Open_lett…

https://x.com/GeorgistSteve/status/1724541886097178997

For the Colorado context (which has fairly strict legal constraints on the property tax system), we recommended a few specific approaches to an LVT shift.

You can read more about them in our Primer available here:

drive.google.com/file/d/1IGgjm3…

You can read more about them in our Primer available here:

drive.google.com/file/d/1IGgjm3…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh