Tu-160M, the "White Swan" is the largest, the heaviest and the fastest bomber in the world. Originally a Soviet design, the plane you see today has limited continuity with the USSR. It was created in late 2010s, as a combined project of Putin's Russia and Siemens Digital Factory

Original Tu-160 was created as a domesday weapon of the Cold War. Designed in the 1970s, it was officially launched into production in 1984. And yet, with the collapse of the Soviet Union the project was aborted. In 1992, their production ceased.

No Nuclear War, no White Swans.

No Nuclear War, no White Swans.

With the fall of USSR, Russia suffered a catastrophic drop in military expenditures. As the state was buying little weaponry (and paying for it highly erratically), entire production chains were wiped out. That included some ultra expensive projects such as strategic bombers.

Yet, it would be incorrect to describe the 1990s developments as a free fall of the military production. To the contrary, the fall was very much unfree. As the Kremlin could not save all of the Soviet military potential, it had to choose what to save.

It chose to save the R&D.

It chose to save the R&D.

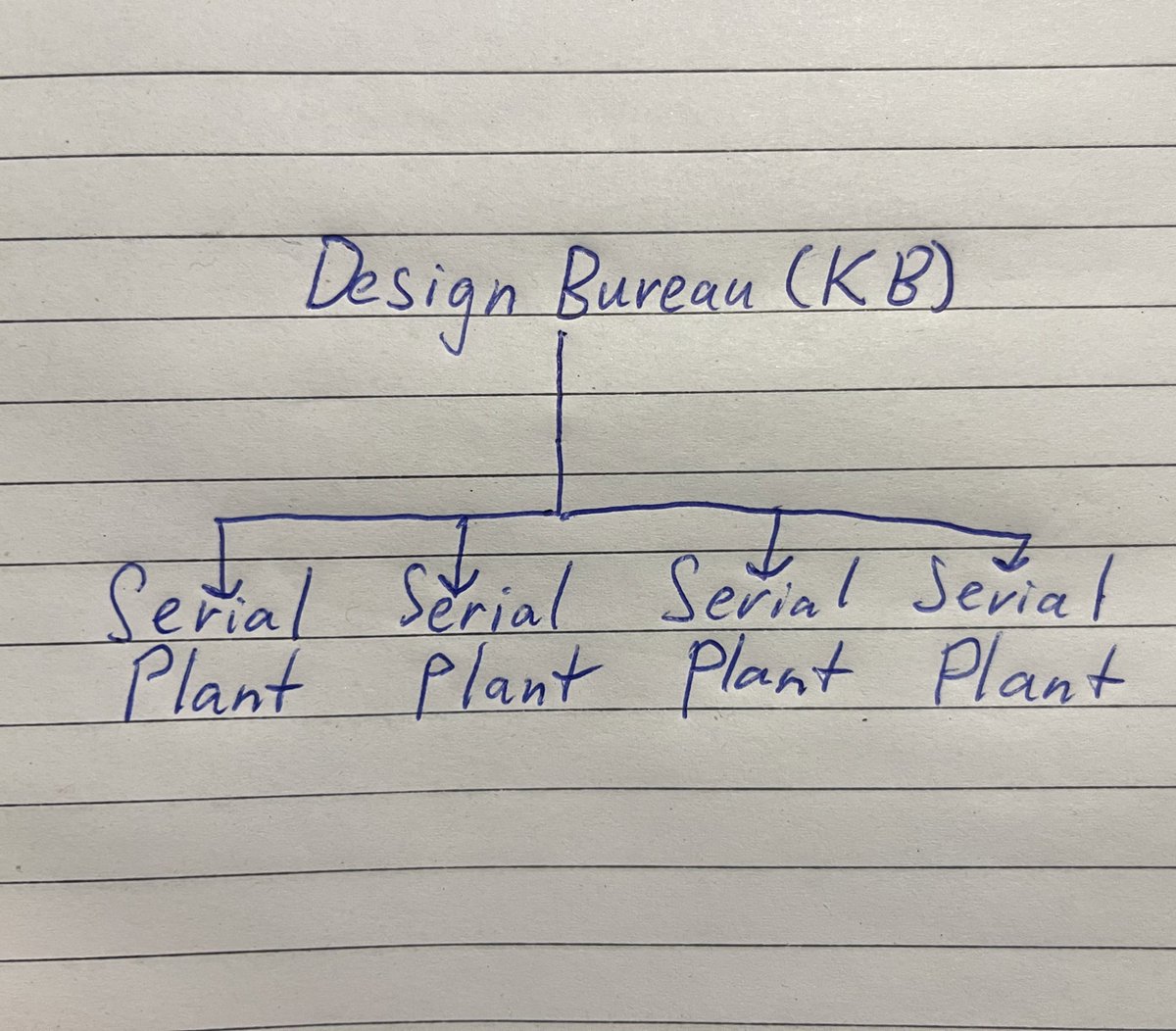

How was the Soviet military industry organised? There were:

1. Design Bureaus, responsible for the R&D

2. Serial Plants, responsible for mass production

In many or most cases, the former were in charge of the latter. KB makes designs and sends them to serial plants to execute.

1. Design Bureaus, responsible for the R&D

2. Serial Plants, responsible for mass production

In many or most cases, the former were in charge of the latter. KB makes designs and sends them to serial plants to execute.

Many of the key Design Bureaus (KB) acted as head offices of large military industrial conglomerates. They had little (or none) production capacities, yet were in charge of serial plants that had lots of them.

KBs held the key knowledge & were relatively cheap to maintain.

KBs held the key knowledge & were relatively cheap to maintain.

In contrast, Serial Plants doing the actual production were costly in maintenance. They had many times more people, equipment. So, once you scale your production down (often to zero), they turn into a suitcase without a handle. Ultra expensive & kinda useless.

At least for now.

At least for now.

As the new government faced harsh financial constraints, it prioritised saving Design Bureaus (= R&D) over the Serial Plants (= production). The former were deemed as more critical, and also very much cheaper to save. So, the latter were largely left to their own fate.

As a result, the Russian R&D capability fared through the 1990s *way* better than the production capability. Russia was preserving the Soviet designs of weaponry, finishing and improving them. Yet, its capacity to execute them was atrophying quickly and seemingly irreversibly.

Still, although the atrophy of production capacities was very much visible across the military industry, not everyone suffered and not everyone deteriorated equally. There was, in fact, a massive asymmetry in this decline.

While the demise of planned economy impoverished most military producers in Russia, it paradoxically enriched some of them. Unlike in the Soviet era, you can't really sell your manufacture to the state. But, unlike in the Soviet era you can potentially *export* it.

As a result, the collapse in government purchases created a massive inequality between those who could not successfully export their manufacture abroad (that is almost everyone), and a handful of highly successful exporters. That is primarily fighters & helicopters producers.

What was Manturov, the Russian Minister for Industry and Trade (= Military Production) in 2012-2024 doing in the 1990s? He was exporting helicopters. As helicopters are exportable, functional helicopter plants were literally a gold mine, even amidst the general collapse.

Why was exporting weaponry such a gold mine? Well, first of all because you can charge more. When selling to the Russian government, you could not really overcharge. The profit margin was low, you were selling almost at the cost of production.

Not the case with Algeria or India

Not the case with Algeria or India

Second, because unlike the Russian government the foreigners would actually pay. In the 1990s Russia went through its crisis of non-payments when the government would simply not pay the bills for the weaponry it ordered, sometimes for years.

Third, because the government ordered very little weaponry anyway.

If the government is ordering almost no weaponry, and is delaying payments for the weaponry it has ordered indefinitely, then you either export or you die.

Now the problem with White Swans is that they were unexportable. Therefore, their production died.

Now the problem with White Swans is that they were unexportable. Therefore, their production died.

After the production was officially ceased in 1992, they still assembled few planes from the details prefrabricated in Soviet era. But that was it. With the production processes interrupted, equipment was lost, the workforce largely gone or retired, and their skills lost forever

After decades of desolation and disrepair, the Russian political leadership decided to revive the project. In 2015, the Ministry of Defense published its plans to restart the production of White Swans. By that point, capacity to produce them had been already gone, long ago.

Even worse, material civilisation that used to produce White Swans did not exist anymore. The supply chains was gone. The production facilities gone. The workers & technologists gone. Most importantly, knowledge ecosystems supporting the production were gone, too, forever.

One could not really "revive" the ancient project created in the context of very different material culture. One could only use it as a foundation for the new project, adapted for the material culture of today. And that is exactly what they did in 2015-2022.

To be continued.

To be continued.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh