What makes Gothic architecture... Gothic?

Many things, but one of the most important is the famous flying buttress.

And they aren't just for show — here's how the flying buttress revolutionised architecture...

Many things, but one of the most important is the famous flying buttress.

And they aren't just for show — here's how the flying buttress revolutionised architecture...

When you think of "Gothic Architecture" what comes to mind?

Probably pointed arches, stained glass windows, gargoyles, and... flying buttresses.

But what is a flying buttress? Are they just for style? Or do they have a purpose?

Probably pointed arches, stained glass windows, gargoyles, and... flying buttresses.

But what is a flying buttress? Are they just for style? Or do they have a purpose?

Gothic architecture appeared in the 12th century.

It had many influences, but the flashpoint was the arrival of the pointed arch, which had been pioneered in Islamic architecture.

Here you can see them at the Mosque of Ibn Tulun in Cairo:

It had many influences, but the flashpoint was the arrival of the pointed arch, which had been pioneered in Islamic architecture.

Here you can see them at the Mosque of Ibn Tulun in Cairo:

Until then churches had been built with the round arch, which had strict structural limitations.

Beautiful in their own way — but generally speaking these churches were monolithic.

Notice the small windows of Lessay Abbey, plus the sheer size of its stonework.

Beautiful in their own way — but generally speaking these churches were monolithic.

Notice the small windows of Lessay Abbey, plus the sheer size of its stonework.

The pointed arch, meanwhile, is much stronger and far more versatile.

So it wasn't just that the appearance of architecture changed in the 12th century — churches also became bigger, their windows larger, and their structural stonework more refined.

All things flowing upwards.

So it wasn't just that the appearance of architecture changed in the 12th century — churches also became bigger, their windows larger, and their structural stonework more refined.

All things flowing upwards.

Stronger, more complex vaulting was also made possible thanks to the pointed arch.

Cathedrals were soon soaring into the sky, and by the 13th century there was essentially a continental race to see who could build the biggest cathedral possible.

Cathedrals were soon soaring into the sky, and by the 13th century there was essentially a continental race to see who could build the biggest cathedral possible.

So the towers grew taller, the arcades higher, and the windows larger — up to a point.

But the trouble is that those huge vaults have an outward thrust.

This means that the walls supporting them have to be incredibly strong, broad, and thick.

But the trouble is that those huge vaults have an outward thrust.

This means that the walls supporting them have to be incredibly strong, broad, and thick.

But Gothic architects wanted to build thinner and narrower walls so they could create large windows and fill them with stained glass — another typical feature of Gothic architecture.

Enter the flying buttress...

Enter the flying buttress...

A buttress is essentially a wall support.

These are some normal buttresses — columns of stone attached to and supporting the wall to prevent it from falling outward.

These are some normal buttresses — columns of stone attached to and supporting the wall to prevent it from falling outward.

The trouble came as the height of cathedrals increased, and when clerestories (a second tier of windows) were built above the aisles.

How to prevent these higher walls from falling?

Build a buttress at the lower level and connect it to the higher wall with an arch.

How to prevent these higher walls from falling?

Build a buttress at the lower level and connect it to the higher wall with an arch.

This crucial invention is what allowed for the creation of such colossal cathedrals which, despite their size, seem somehow graceful and weightless.

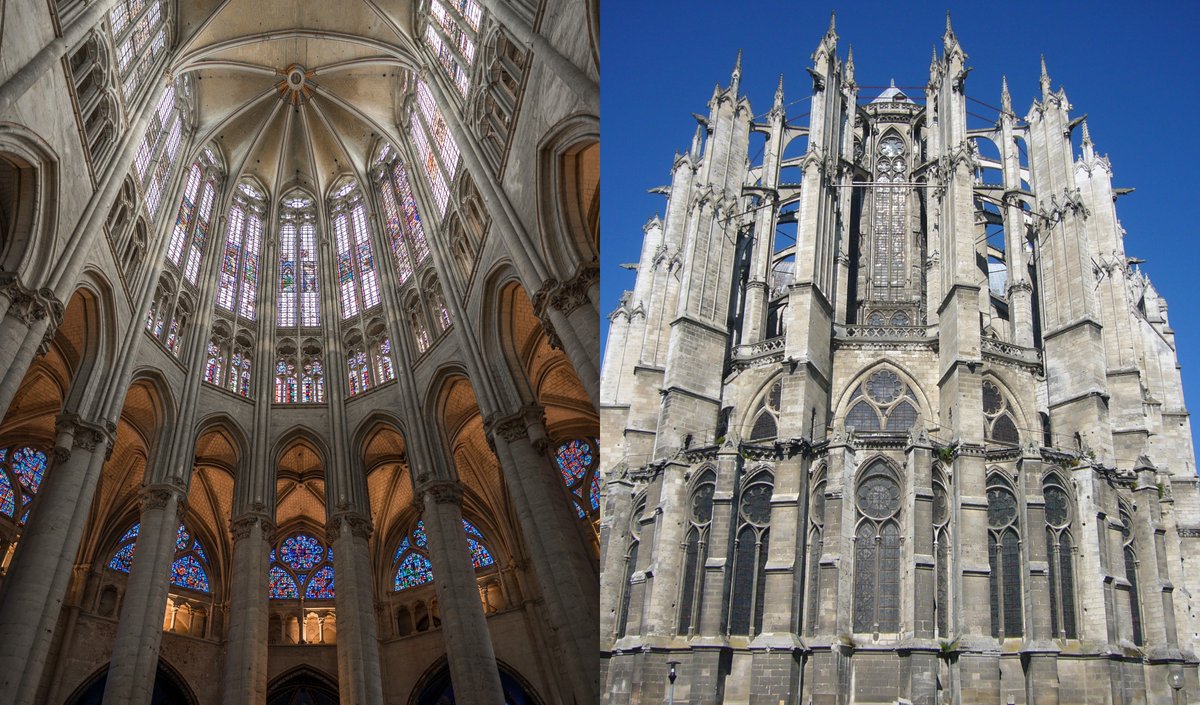

Thus High Gothic cathedrals essentially became huge stone frameworks filled with painted glass, as at Beauvais:

Thus High Gothic cathedrals essentially became huge stone frameworks filled with painted glass, as at Beauvais:

But, even if they were functional — without them cathedrals would collapse — the aesthetic value of flying buttresses quickly became obvious.

Just look at the Notre Dame, where flying buttresses radiate like the roots of a tree, cascade like a waterfall of stone.

Just look at the Notre Dame, where flying buttresses radiate like the roots of a tree, cascade like a waterfall of stone.

What about those small stone spires on top of the buttresses? These are called "pinnacles".

These, too, served an important function.

They add weight to the buttress, thus making it stronger and more resistant to outward thrust.

These, too, served an important function.

They add weight to the buttress, thus making it stronger and more resistant to outward thrust.

The consequence of all this — the combination of flying buttresses and pinnacles — was that the walls of Gothic churches were essentially turned at a right angle to the structure.

You can see how that opened up space for larger windows.

You can see how that opened up space for larger windows.

But both pinnacles and flying buttresses, despite being functional architectural elements, were transformed into artistic wonders of their own, covered in statues and lavish decoration.

Such was the Medieval way — that which was functional must also, necessarily, be beautiful.

Such was the Medieval way — that which was functional must also, necessarily, be beautiful.

Look back to the days of Romanesque Architecture, where the cathedral's exterior is basically composed of a series of flat surfaces.

This is Southwell Minster — the large window you can see here is newer than the rest of the simpler, Romanesque building.

This is Southwell Minster — the large window you can see here is newer than the rest of the simpler, Romanesque building.

And compare that to a High Gothic cathedral, where your eye can hardly rest on a single, flat surface.

All is much more three-dimensional, all is moving, all is perforated and fluid.

More like a web of stone than a solid structure.

All is much more three-dimensional, all is moving, all is perforated and fluid.

More like a web of stone than a solid structure.

The effectiveness and beauty of flying buttresses was such that they were often employed at ground level, even when they were not strictly necessary.

So a good way to think of flying buttresses is as the Medieval equivalent of something like the X-bracing on some modern skyscrapers — in this case the John Hancock Center.

Structural features that make a building stronger, allow it to be taller, and also add aesthetic value.

Structural features that make a building stronger, allow it to be taller, and also add aesthetic value.

In the later years of Gothic Architecture flying buttresses were employed copiously and needlessly.

Whereas once they had been functional, they became purely and self-consciously aesthetic rather than structural

As on the tower at the Church of St Ouen:

Whereas once they had been functional, they became purely and self-consciously aesthetic rather than structural

As on the tower at the Church of St Ouen:

But they eventually disappeared altogether — with the rise of neoclassical architecture during the Renaissance.

The round arch returned, the pointed arch was banished, and flying buttresses were consigned to history...

The round arch returned, the pointed arch was banished, and flying buttresses were consigned to history...

But these strange, striking tendrils of stone have long since become interminably associated with Gothic Architecture.

And rightly so — because flying buttresses are the thing that, in so many ways, makes the Gothic possible.

And rightly so — because flying buttresses are the thing that, in so many ways, makes the Gothic possible.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh