Frank Lloyd Wright was born 157 years ago today.

People usually call him the greatest American architect of all time — here's why...

People usually call him the greatest American architect of all time — here's why...

Frank Lloyd Wright was born in Wisconsin on 8th June 1867 and died in 1959.

So his life spanned immense changes, on a global scale, to pretty much every aspect of society.

Over the course of a seven decade career Wright designed 1,114 buildings, of which 532 were built.

So his life spanned immense changes, on a global scale, to pretty much every aspect of society.

Over the course of a seven decade career Wright designed 1,114 buildings, of which 532 were built.

The majority of his designs were for houses.

It was the home, the most ancient and important building of all, that fascinated him more than anything else.

Wright wanted to help modernise the way Americans lived — and, crucially, modernise living in the right way.

It was the home, the most ancient and important building of all, that fascinated him more than anything else.

Wright wanted to help modernise the way Americans lived — and, crucially, modernise living in the right way.

Wright also designed galleries, museums, churches, and all manner of other buildings.

It's hard to grasp how radical he was, but by comparing his Unity Temple with other churches built in the same year — 1908 — you can see this clearly.

An entirely new style.

It's hard to grasp how radical he was, but by comparing his Unity Temple with other churches built in the same year — 1908 — you can see this clearly.

An entirely new style.

One of the biggest influences on Wright was Louis Sullivan, for whom he worked in the 1880s.

Sullivan, based in Chicago, almost singlehandedly adapted the old rules of architecture to skyscrapers, which were then a new kind of building nobody really knew how to design.

Sullivan, based in Chicago, almost singlehandedly adapted the old rules of architecture to skyscrapers, which were then a new kind of building nobody really knew how to design.

Wright also designed offices — like the Larkin Administration Building, built in 1903 and demolished in 1950.

The first thing you notice about the interior of any Wright building is its space — how open everything is, how all rooms are connected, how light pours in.

The first thing you notice about the interior of any Wright building is its space — how open everything is, how all rooms are connected, how light pours in.

What's the best way to think of Frank Lloyd Wright?

Despite his fame and success — as an outsider.

Concrete and steel (among other things) revolutionised architecture, and they led European modernists to design things like this, Adolf Loos' Steiner Hause in Vienna, from 1910:

Despite his fame and success — as an outsider.

Concrete and steel (among other things) revolutionised architecture, and they led European modernists to design things like this, Adolf Loos' Steiner Hause in Vienna, from 1910:

But Wright refused to accept that the "International Style" (as European modernism came to be known) was the inevitable conclusion of these new methods and machines.

He agreed that architecture had been liberated; he disagreed about what its new style should be.

He agreed that architecture had been liberated; he disagreed about what its new style should be.

Wright was actually a generation older than the modernists in Europe, and his ideas were a direct, major influence on them.

Like them he discarded the old styles and fully embraced modern methods.

But his aesthetic results were different — and, ultimately, less scalable.

Like them he discarded the old styles and fully embraced modern methods.

But his aesthetic results were different — and, ultimately, less scalable.

Wright's first major contribution was with the "Prairie School" at the beginning of the 1900s.

Local materials, large eaves, and a horizontal shape supposed to evoke the prairies.

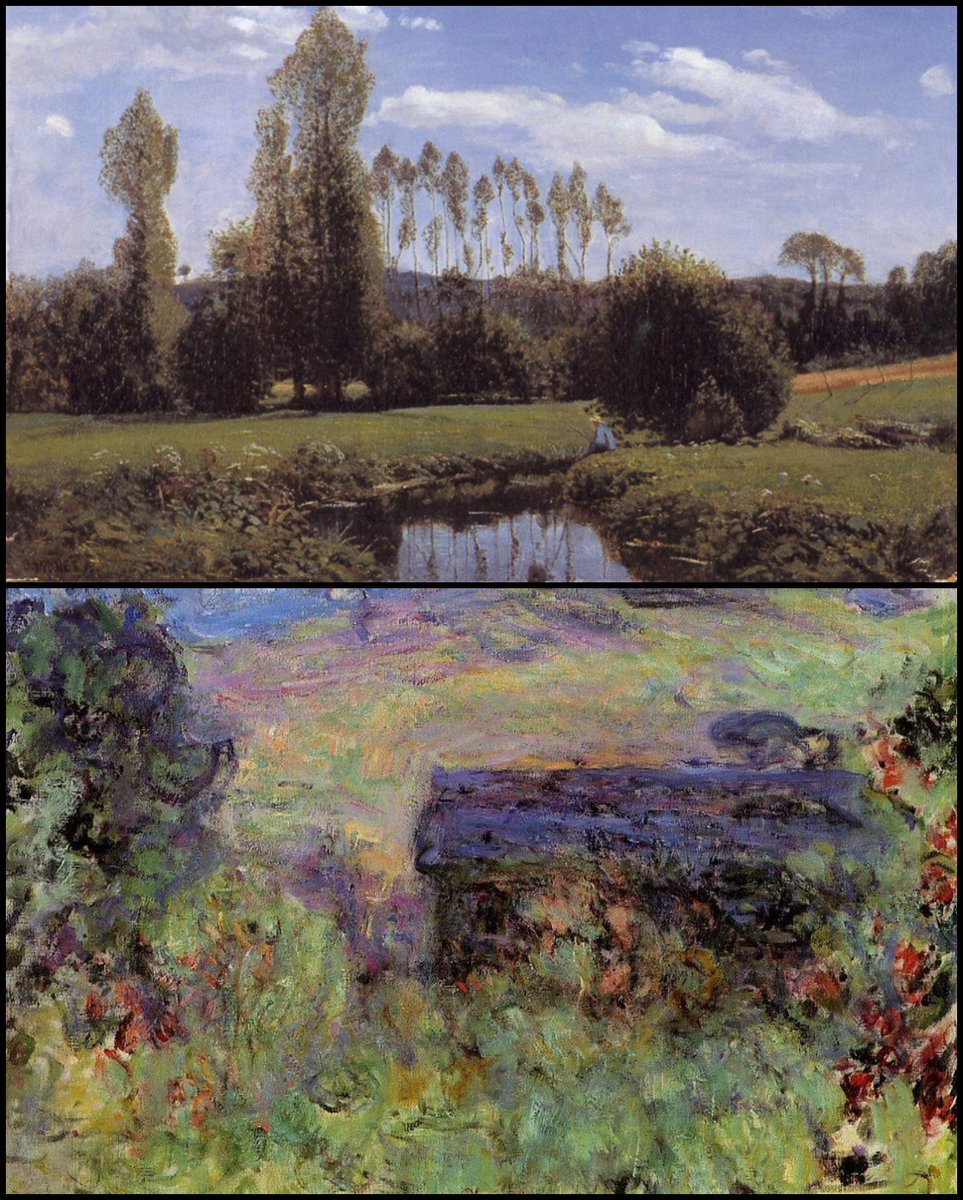

By comparing them with his earlier work you can see, again, what a major change it was.

Local materials, large eaves, and a horizontal shape supposed to evoke the prairies.

By comparing them with his earlier work you can see, again, what a major change it was.

These ideas later developed, during the 1930s, into a style Wright called "Usonian".

Small, one storey houses made from a rich variety of materials, with extended eaves and a heavy horizontal emphasis.

His dream was to improve — and beautify — the very concept of the home.

Small, one storey houses made from a rich variety of materials, with extended eaves and a heavy horizontal emphasis.

His dream was to improve — and beautify — the very concept of the home.

Wright was fascinated by space and believed the way houses were usually built — with small, divided rooms — needed to change.

Open plan interiors are incredibly common now, and that is partly thanks to the work and ideas of Frank Lloyd Wright.

Open plan interiors are incredibly common now, and that is partly thanks to the work and ideas of Frank Lloyd Wright.

Ultimately, Wright wanted to create a uniquely American style.

It would be enabled by modern methods and free from European traditions, but still in harmony with nature and built according to democratic, emotional, and humane rather than industrial and abstract principles.

It would be enabled by modern methods and free from European traditions, but still in harmony with nature and built according to democratic, emotional, and humane rather than industrial and abstract principles.

Being "in harmony with nature" sounds vague, but look at his work.

His larger projects — like the Guggenheim, Marin County Civic Center, or Johnson Wax Headquarters — are defined by curves, asymmetry, and varied shapes.

He didn't like the box-shaped buildings popular in Europe.

His larger projects — like the Guggenheim, Marin County Civic Center, or Johnson Wax Headquarters — are defined by curves, asymmetry, and varied shapes.

He didn't like the box-shaped buildings popular in Europe.

Wright loved to use warm colours, a range of materials, and a variety of textures.

His horizontal houses thus feel like part of the landscape; their ceaseless variation and interplay of light and shadow were a reinterpretation of nature.

He called it "organic architecture".

His horizontal houses thus feel like part of the landscape; their ceaseless variation and interplay of light and shadow were a reinterpretation of nature.

He called it "organic architecture".

Compare Wright's houses to those being designed by European modernists at the same time.

People like Le Corbusier and Mies favoured bold, simple geometry and smooth white surfaces.

Clean and futuristic, but Wright's architecture looks cozy, intimate, and natural by comparison.

People like Le Corbusier and Mies favoured bold, simple geometry and smooth white surfaces.

Clean and futuristic, but Wright's architecture looks cozy, intimate, and natural by comparison.

His tastes were very eclectic, and the art and aesthetic principles of Japan were a particularly importance influence on his ideas — as he explains here.

Wright wrote with a religious tone, and often adopted a quasi-prophetic register.

Wright wrote with a religious tone, and often adopted a quasi-prophetic register.

Wright also designed furniture, fittings, and other elements of interior design.

Like the Arts & Crafts Movement of 19th century Britain, like the Art Nouveau in France and Belgium, like the Bauhaus in Germany, he was interested in creating a unified, total aesthetic.

Like the Arts & Crafts Movement of 19th century Britain, like the Art Nouveau in France and Belgium, like the Bauhaus in Germany, he was interested in creating a unified, total aesthetic.

Perhaps the best example of his experimental mindset is the use of "textile blocks" — concrete blocks imprinted with texture or pattern.

A novel way to make the monotony of concrete more interesting; his express purpose was to turn something ugly into something beautiful.

A novel way to make the monotony of concrete more interesting; his express purpose was to turn something ugly into something beautiful.

Or consider his ideas about urban planning.

Broadacre City (above) and Crystal Heights (below) were two major, unbuilt projects that embodied Wright's radical concept of what American cities could and should look like.

Broadacre City (above) and Crystal Heights (below) were two major, unbuilt projects that embodied Wright's radical concept of what American cities could and should look like.

The influence of Frank Lloyd Wright is hard to estimate.

His fame was huge and his legend has only grown — Wright's name is as big as it gets for an architect.

The impact of his innovations in technology, open planning, and stylistic evolution are incalculably large.

His fame was huge and his legend has only grown — Wright's name is as big as it gets for an architect.

The impact of his innovations in technology, open planning, and stylistic evolution are incalculably large.

But certain artists are unique in a way that renders their influence diffuse rather than direct.

In the same way that Leonardo's experimental methods meant his paintings deteriorated quickly, that his ways were hard to imitate, Wright's specific style is hard to replicate.

In the same way that Leonardo's experimental methods meant his paintings deteriorated quickly, that his ways were hard to imitate, Wright's specific style is hard to replicate.

Still, Wright's influence on the European modernists — although they ultimately diverged from his core principles — and on American design are both colossal.

The world of today is not the world Wright would have designed, but it wouldn't look the way it does now without him.

The world of today is not the world Wright would have designed, but it wouldn't look the way it does now without him.

Of course, none of this has mentioned Wright's eccentric personality, his domestic troubles, his chaotic life, his many highs and many lows.

But how to summarise it all? Frank Lloyd Wright achieved his dream — he created a uniquely American style of architecture.

But how to summarise it all? Frank Lloyd Wright achieved his dream — he created a uniquely American style of architecture.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh