The words "Japanese architecture" are incredibly broad and could refer to hundreds of different things.

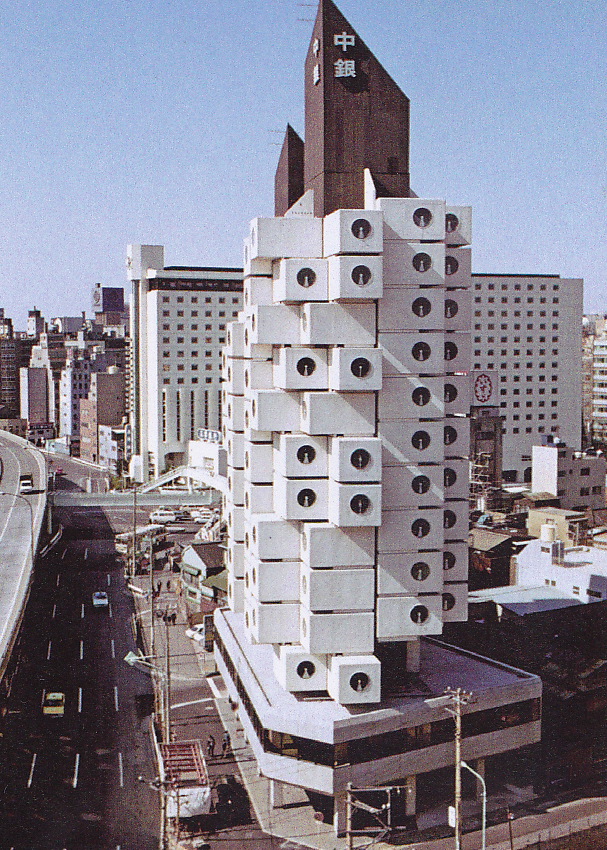

Like Metabolism, an unusual and short-lived style that emerged in the late 1950s, epitomised by the now-demolished Nakagin Capsule Tower:

Like Metabolism, an unusual and short-lived style that emerged in the late 1950s, epitomised by the now-demolished Nakagin Capsule Tower:

And what about Japanese urban design more broadly?

Something distinctive about Japanese streets, for example, is that they often lack raised pavements and that there is rarely any on-street parking.

Something distinctive about Japanese streets, for example, is that they often lack raised pavements and that there is rarely any on-street parking.

Still, the first thing people usually think of when they hear the words "Japanese architecture" is probably a building like Kinkaku-ji, the Temple of the Golden Pavilion, in Kyoto.

Traditional Japanese architecture at its finest — but what makes it look like that?

Traditional Japanese architecture at its finest — but what makes it look like that?

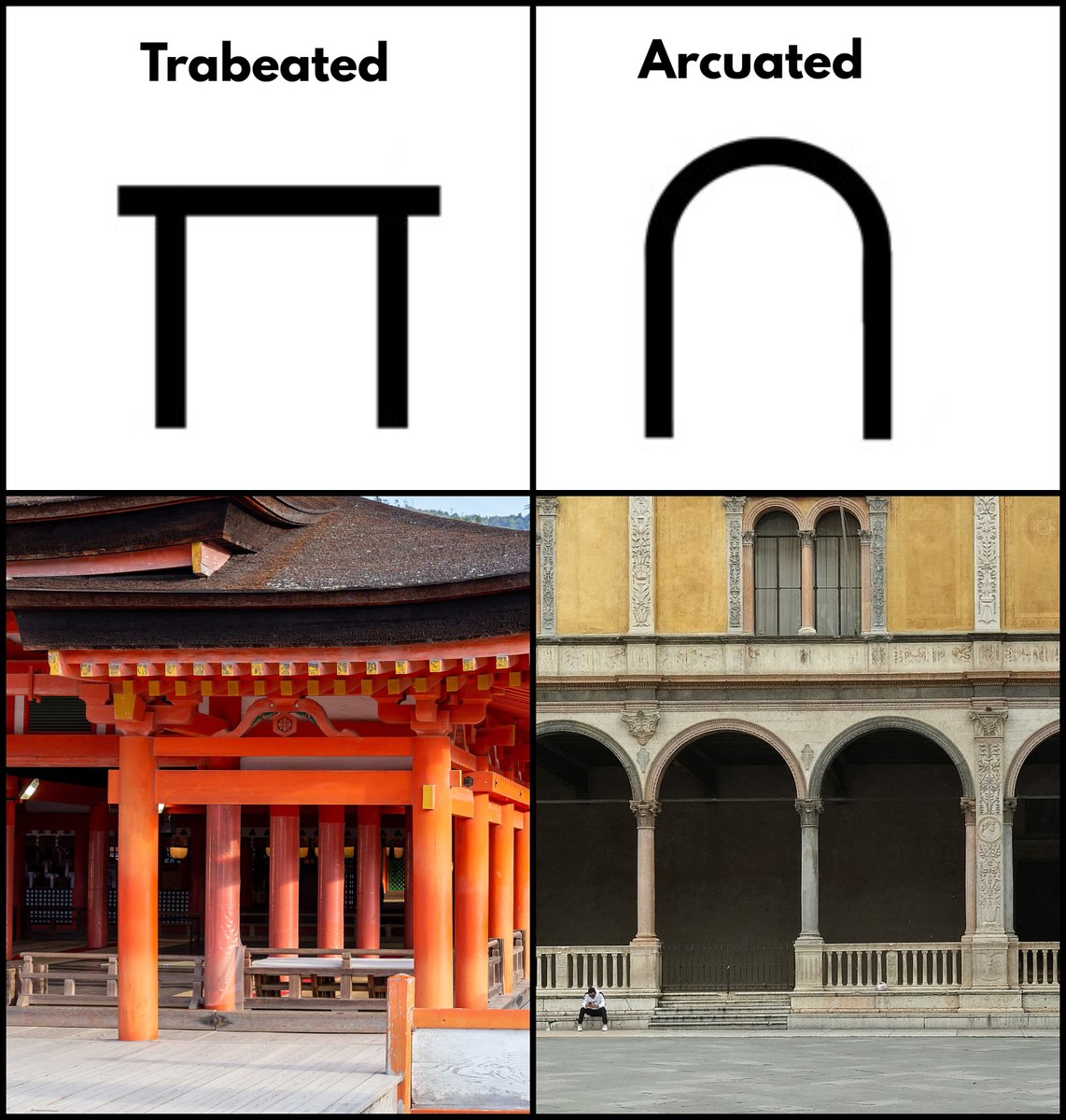

The first thing to say about traditional Japanese architecture is that it is fundamentally trabeated.

This means its basic unit is the post and lintel, as opposed to the arch.

Something it has in common with Ancient Greek and Ancient Egyptian architecture, for example.

This means its basic unit is the post and lintel, as opposed to the arch.

Something it has in common with Ancient Greek and Ancient Egyptian architecture, for example.

Over the top of this trabeated structure is inevitably built a very large roof.

They are usually either hip roofs or hip-and-gable roofs — four sides run down from the top, but at either end there is also a gable (i.e. the triangular part), below which the roof continues.

They are usually either hip roofs or hip-and-gable roofs — four sides run down from the top, but at either end there is also a gable (i.e. the triangular part), below which the roof continues.

Another defining quality is the eaves, which thrust far outward and cast heavy shadows over a building's walls and entrances.

So: a post-and-lintel structure supporting a hip-and-gable roof with extended eaves is the basic model of traditional Japanese architecture.

So: a post-and-lintel structure supporting a hip-and-gable roof with extended eaves is the basic model of traditional Japanese architecture.

These eaves, because they project so far from the walls of the building, are usually supported by a series of elaborately stacked brackets.

A functionally necessary architectural feature that is also used for ornamental purposes.

A functionally necessary architectural feature that is also used for ornamental purposes.

This broad model applies — with plenty of variation and many exceptions, of course — to all the most famous Japanese temples, shrines, and even castles.

Think of something like Yakushi-ji in Nara: with extended eaves and heavy shadows, it is a temple dominated by its roofs.

Think of something like Yakushi-ji in Nara: with extended eaves and heavy shadows, it is a temple dominated by its roofs.

It also applies to gates, which are a vital and ubiquitous feature of traditional Japanese architecture — like the Great South Gate at Tōdai-ji.

Of course, ceremonial gates are common around the world, from Roman triumphal arches to the Islamic iwan.

Of course, ceremonial gates are common around the world, from Roman triumphal arches to the Islamic iwan.

But alongside entrance gates designed on the broader building model, there are also torii — the most famous of which is surely that of the Itsukushima Shrine.

A symbolic gateway that marks the boundary between the sacred and the profane at Shinto shrines.

A symbolic gateway that marks the boundary between the sacred and the profane at Shinto shrines.

Even the bell towers in Japanese temples are built with the same model and have their own trabeate structure, hip-and-gable roofs, and thrusting eaves.

They also stand independent of other buildings rather than being integrated like church belfries.

They also stand independent of other buildings rather than being integrated like church belfries.

But that's not all — traditional Japanese architecture is also defined by its setting.

The gardens that surround a temple are as much a part of the architectural style as the buildings themselves.

Like Kinkaku-ji — move it anywhere else and it would not be the same.

The gardens that surround a temple are as much a part of the architectural style as the buildings themselves.

Like Kinkaku-ji — move it anywhere else and it would not be the same.

Whereas churches and mosques seem to be closed off from the natural world, Japanese temples feel integrated into their landscape.

You could rebuild Rouen Cathedral or the Bibi-Khanym Mosque elsewhere without loss of effect.

Which isn't a problem — just a stylistic difference.

You could rebuild Rouen Cathedral or the Bibi-Khanym Mosque elsewhere without loss of effect.

Which isn't a problem — just a stylistic difference.

And it is this quality of integration, of openness to and involvement with the lakes, forests, paths, trees, flowers, and gardens around them — all of which have been carefully crafted — that gives Japanese temples and shrines their uniquely harmonious and peaceful atmosphere.

And, again, whereas the word church or mosque tends to conjure the image of a single grand building, the Shinto shrine or Buddhist temple is a complex of many buildings.

Each have their own purpose and unique design features, but all are united in structure and aesthetic.

Each have their own purpose and unique design features, but all are united in structure and aesthetic.

Another important factor in all of this is that traditional Japanese architecture is wooden.

Stone was used in some places, mainly for foundations and bases, but wood was the rule.

Hence the fire risk and the endless rebuilding of temples down the centuries.

Stone was used in some places, mainly for foundations and bases, but wood was the rule.

Hence the fire risk and the endless rebuilding of temples down the centuries.

That being said, most global architectures emerged as wood, including Ancient Greek architecture — its features are all transmutations of wood into stone.

So why did Japan stick with wood? There are several reasons, and they shaped its architecture as a whole.

So why did Japan stick with wood? There are several reasons, and they shaped its architecture as a whole.

See, the humid climate of Japan forced builders to raise their structures above ground level and give them plenty of open space for ventilation.

Hence the peculiar "openness" of Japanese architecture, and even those famous sliding doors.

Hence the peculiar "openness" of Japanese architecture, and even those famous sliding doors.

Meanwhile the heavy rains of Japan are likely what drove the development of those wonderful, thrusting eaves — to protect the building from rainfall.

And the strong winds that came with typhoons meant large and heavy roofs, covered in tiles, were also necessary.

And the strong winds that came with typhoons meant large and heavy roofs, covered in tiles, were also necessary.

Could all of that not be done with stone?

Perhaps, but the problem in Japan is earthquakes.

And wooden buildings, because of their flexibility, are far more resistant to earthquakes than stone — there was essentially no other choice.

Perhaps, but the problem in Japan is earthquakes.

And wooden buildings, because of their flexibility, are far more resistant to earthquakes than stone — there was essentially no other choice.

Does that mean Japanese architecture can be explained entirely as a response to local climate and geography?

In some ways, but so too can all traditional design around the world — this is called vernacular architecture.

Design suited to local needs and restrictions.

In some ways, but so too can all traditional design around the world — this is called vernacular architecture.

Design suited to local needs and restrictions.

But the context of climate and geography is only the starting point.

From those local restrictions inevitably flow a profusion of traditions and regional idiosyncrasies.

Like the art and decoration of Japanese architecture, for example, which hasn't been mentioned here.

From those local restrictions inevitably flow a profusion of traditions and regional idiosyncrasies.

Like the art and decoration of Japanese architecture, for example, which hasn't been mentioned here.

Of course, it's important to note that many elements of traditional Japanese architecture are shared with surrounding countries.

Like the pagoda, which arrived in Japan from China (along with so much else) where it had evolved from the Indian stupa.

Like the pagoda, which arrived in Japan from China (along with so much else) where it had evolved from the Indian stupa.

And, needless to say, plenty has been elided — there is far more to all this than trabeation, large hip or hip-and-gable roofs, thrusting eaves, and integration with the landscape.

But they are a good starting point for understanding traditional Japanese architecture.

But they are a good starting point for understanding traditional Japanese architecture.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh