📢New WP!📢 The Class Gap in Career Progression: Evidence from US Academia, w/ Kyra Rodriguez

Class is rarely a focus of research or DEI in elite US occupations.

Evidence suggests it should be: we find a large class gap in at least one occupation - tenure-track academia...🧵

Class is rarely a focus of research or DEI in elite US occupations.

Evidence suggests it should be: we find a large class gap in at least one occupation - tenure-track academia...🧵

📖🎓SETTING: US tenure-track academia

📈📉DATA: NSF's Survey of Doctorate Recipients 1993-2021.

This is a representative sample of all graduates of US PhD programs in STEM and Social Sciences. We see snapshots of the careers of tens of thousands of people. (2/22)

📈📉DATA: NSF's Survey of Doctorate Recipients 1993-2021.

This is a representative sample of all graduates of US PhD programs in STEM and Social Sciences. We see snapshots of the careers of tens of thousands of people. (2/22)

❓How to measure class❓

We use PARENTAL EDUCATION🧑🎓

- first-gen college grads

- parent w/ BA

- parent w/ non-PhD grad degree (JD, MD, MBA, EdM...)

We're less interested in PhD parents b/c it reflects academia-specific advantage, not generalized socioeconomic advantage. (3/22)

We use PARENTAL EDUCATION🧑🎓

- first-gen college grads

- parent w/ BA

- parent w/ non-PhD grad degree (JD, MD, MBA, EdM...)

We're less interested in PhD parents b/c it reflects academia-specific advantage, not generalized socioeconomic advantage. (3/22)

🚨We find a large class gap:🚨

*Conditional on PhD program attended*, first-gen college grads are

➡️13% less likely to end up tenured at an R1, and

➡️ tenured at places ranked 9% lower

compared to their PhD classmates who had a parent with a (non-PhD) graduate degree. (4/22)

*Conditional on PhD program attended*, first-gen college grads are

➡️13% less likely to end up tenured at an R1, and

➡️ tenured at places ranked 9% lower

compared to their PhD classmates who had a parent with a (non-PhD) graduate degree. (4/22)

This class gap between PhD classmates arises on the post-PhD job market.

*In addition*, when we look at the tenure decision point, we see a large class gap in the rate of getting tenure - even conditional on fixed effects for tenure-track institution. (5/22)

*In addition*, when we look at the tenure decision point, we see a large class gap in the rate of getting tenure - even conditional on fixed effects for tenure-track institution. (5/22)

The gap is *not* driven by differential selection out of academia into industry. There's no class gap in ending up tenured *anywhere* conditional on PhD - the class gap exists entirely on the intensive margin - WHERE someone is tenured.

(This was surprising to us). (6/22)

(This was surprising to us). (6/22)

Why might this gap emerge? We can explore a few mechanisms:

1⃣ Research Productivity

2⃣ Networks

3⃣ Choice/Preferences

(7/22)

1⃣ Research Productivity

2⃣ Networks

3⃣ Choice/Preferences

(7/22)

RESEARCH: If we see lower-SEB academics producing less research than their former PhD classmates, this could be because of

- differential ENDOWMENTS of research ability pre-PhD, or

- differential opportunities to DEVELOP their research ability during PhD & tenure track. (8/22)

- differential ENDOWMENTS of research ability pre-PhD, or

- differential opportunities to DEVELOP their research ability during PhD & tenure track. (8/22)

Re-running our baseline regressions controlling for research closes at most a third of the class gap.

Among those tenured at ranked institutions, there is still an 11% class gap in rank - even conditional on highly detailed measures of research quantity and quality! (9/22)

Among those tenured at ranked institutions, there is still an 11% class gap in rank - even conditional on highly detailed measures of research quantity and quality! (9/22)

This comes mostly from higher-SEB academics being more likely to be “overplaced” – tenured at institutions that are higher-ranked than you’d predict given their research record

– and not so much from lower-SEB academics being more likely to be “underplaced”.

(10/22)

– and not so much from lower-SEB academics being more likely to be “underplaced”.

(10/22)

If research doesn't close most of the class gap, suggests something else must be at play.

Another candidate: NETWORKS

Differential social & cultural capital, as well as homophily, could make it harder for lower-SEB academics to form valuable professional relationships (11/22)

Another candidate: NETWORKS

Differential social & cultural capital, as well as homophily, could make it harder for lower-SEB academics to form valuable professional relationships (11/22)

This can affect both

*actual research output* (less mentorship, fewer collaborators) as well as

*signals of research output* (lower quality recommendation & tenure letters, fewer seminar invites, award opportunities, citations)

Both of these will matter for tenure.

(12/22)

*actual research output* (less mentorship, fewer collaborators) as well as

*signals of research output* (lower quality recommendation & tenure letters, fewer seminar invites, award opportunities, citations)

Both of these will matter for tenure.

(12/22)

We find evidence of weaker coauthorship networks for lower-SEB academics:

1. COAUTHOR HOMOPHILY: first-gen college grads are more likely to coauthor with other first-gen college grads than you would predict from coauthors' characteristics (inst, field, race, gender, etc) (13/22)

1. COAUTHOR HOMOPHILY: first-gen college grads are more likely to coauthor with other first-gen college grads than you would predict from coauthors' characteristics (inst, field, race, gender, etc) (13/22)

(suggestive of frictions to forming prof. relationships across SEB, and thus smaller networks, since most academics at elite institutions have elite backgrounds...) (14/22)

2. LESS WELL-PUBLISHED COAUTHORS: first-gen college grads' coauthors are less well-published - in terms of publications, citations, or journal impact factor - than you would predict from these coauthors' other characteristics (institution, field, race, gender, SEB, etc).

(15/22)

(15/22)

We also find that lower-SEB academics are *less likely to receive NSF awards* than their higher-SEB peers

- even conditional on employer institution, tenure status, detailed measures of prior publication record, *and* prior NSF award receipt.

(16/22)

- even conditional on employer institution, tenure status, detailed measures of prior publication record, *and* prior NSF award receipt.

(16/22)

Finally, we look at CHOICE: do lower-SEB academics choose to work at lower-ranked schools for other reasons?

We don't find any action on this - whether we look at financial, family, or location constraints, institution type, or self-reported preferences. (17/22)

We don't find any action on this - whether we look at financial, family, or location constraints, institution type, or self-reported preferences. (17/22)

Does this matter for other quality of life outcomes?

Yes - the class gap in institution type ALSO comes alongside a class pay gap in academia, and a class gap in job satisfaction.

(18/22)

Yes - the class gap in institution type ALSO comes alongside a class pay gap in academia, and a class gap in job satisfaction.

(18/22)

(Note also: the class gap is NOT driven by other correlated characteristics, like race. We control for race/ethnicity and birth region fixed effects in all our specifications, and we find a class gap even among White non-Hispanic US-born academics.) (19/22).

Is this just about academia?

NO. There is also a class gap in career progression for PhDs in industry. Specifically: a pay gap, a gap in job satisfaction, and widening gaps in pay and in managerial responsibilities over the career (conditional on baseline FEs). (20/22).

NO. There is also a class gap in career progression for PhDs in industry. Specifically: a pay gap, a gap in job satisfaction, and widening gaps in pay and in managerial responsibilities over the career (conditional on baseline FEs). (20/22).

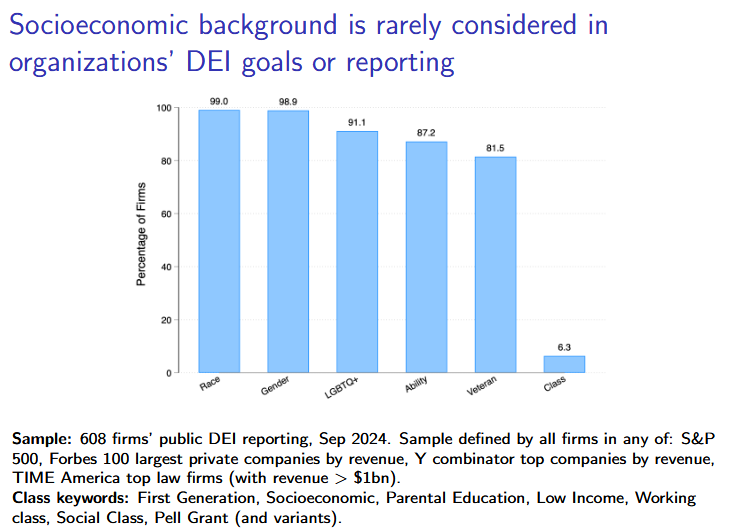

We see these results as relevant across elite labor markets, not just in academia.

DEI efforts across elite occupations almost never mention class background, and data is rarely collected. This is a problematic omission!

(21/22)

hbr.org/2021/01/the-fo…

DEI efforts across elite occupations almost never mention class background, and data is rarely collected. This is a problematic omission!

(21/22)

hbr.org/2021/01/the-fo…

This paper and a great growing lit in sociology tells us that we need *much more work* to examine class – like we do race and gender – and its role in elite labor markets.

Here's the paper!

(/end)annastansbury.github.io/website/Stansb…

Here's the paper!

(/end)annastansbury.github.io/website/Stansb…

PS: My coauthor Kyra Rodriguez is a superb incoming PhD student at @BerkeleyHaas , who has been working with me at MIT these last two years. Keep your eyes out for her!

linkedin.com/in/kyrarodrigu…

linkedin.com/in/kyrarodrigu…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh