The Rosetta Stone was discovered exactly 225 years ago today — inside the wall of an old fortress that was being demolished.

This is the strange story of the stone that brought Ancient Egypt back to life...

This is the strange story of the stone that brought Ancient Egypt back to life...

Why is it called the Rosetta Stone?

Because it was discovered near a town called Rashid in northern Egypt — when the French invaded in the late 18th century they corrupted its name to Rosetta.

Because it was discovered near a town called Rashid in northern Egypt — when the French invaded in the late 18th century they corrupted its name to Rosetta.

So, there are three parts to this story.

First: what is it?

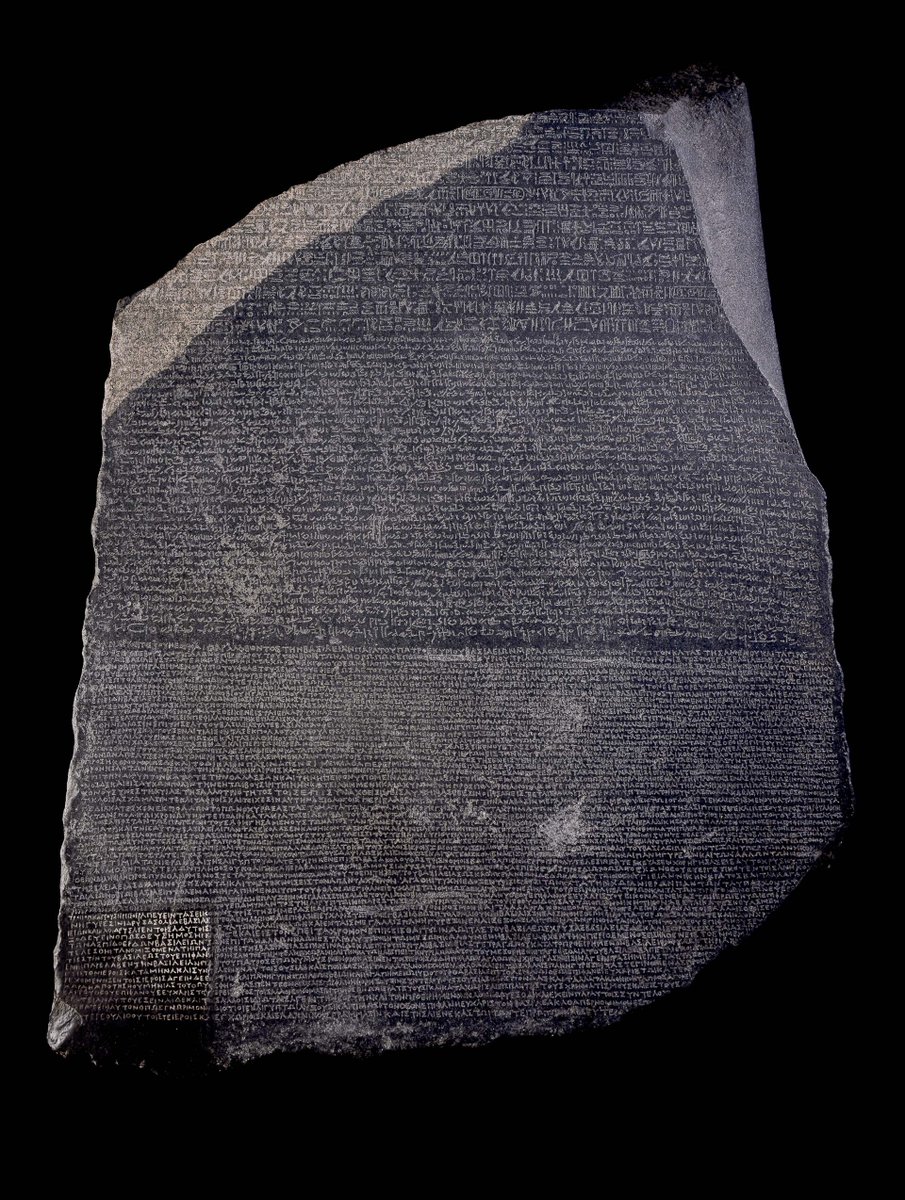

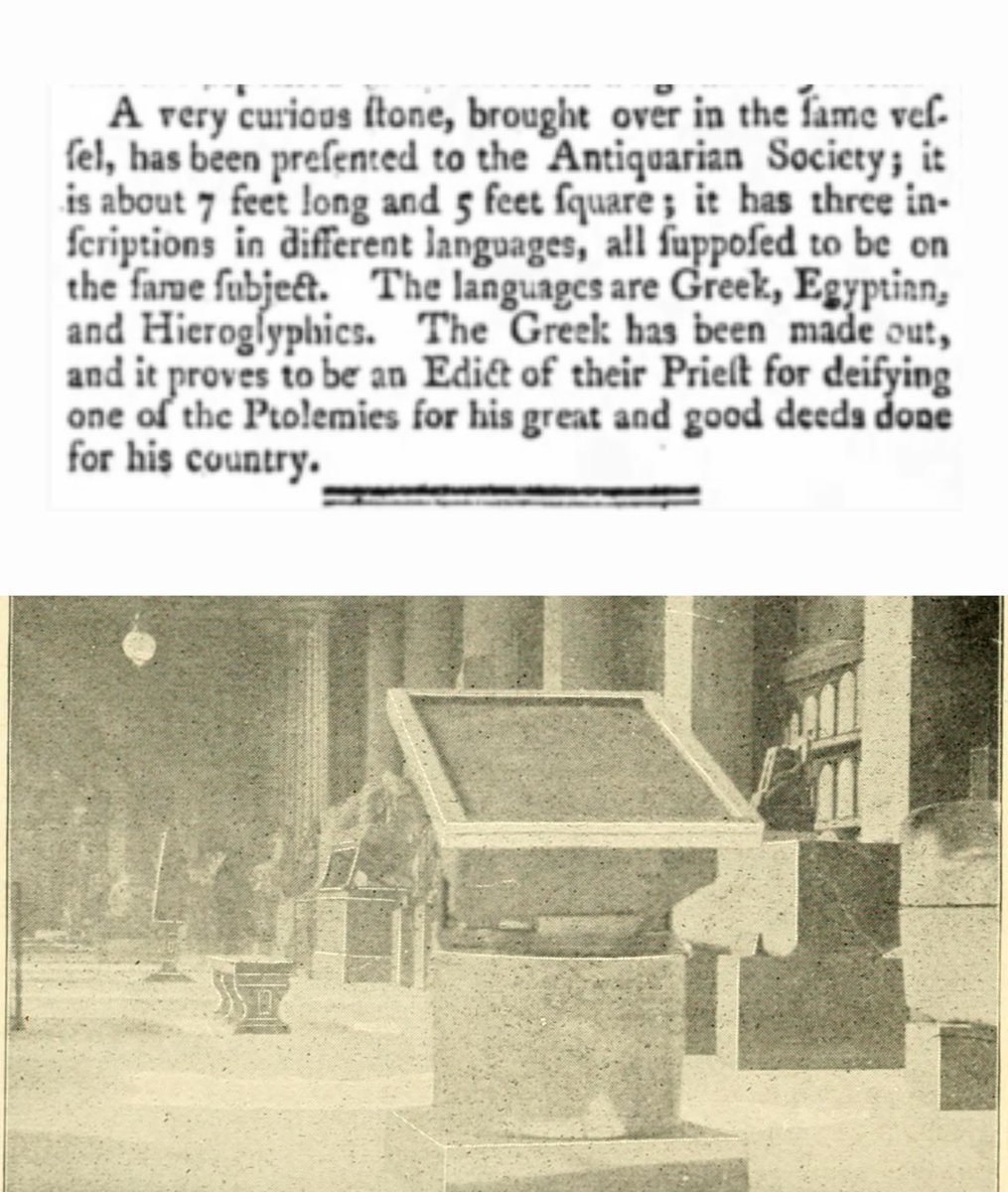

The Rosetta Stone is a slab of granodiorite (a rock similar to granite) mined at Aswan in southern Egypt; it's over 1 metre tall, 3/4 of a metre wide, and weighs 3/4 of a tonne.

First: what is it?

The Rosetta Stone is a slab of granodiorite (a rock similar to granite) mined at Aswan in southern Egypt; it's over 1 metre tall, 3/4 of a metre wide, and weighs 3/4 of a tonne.

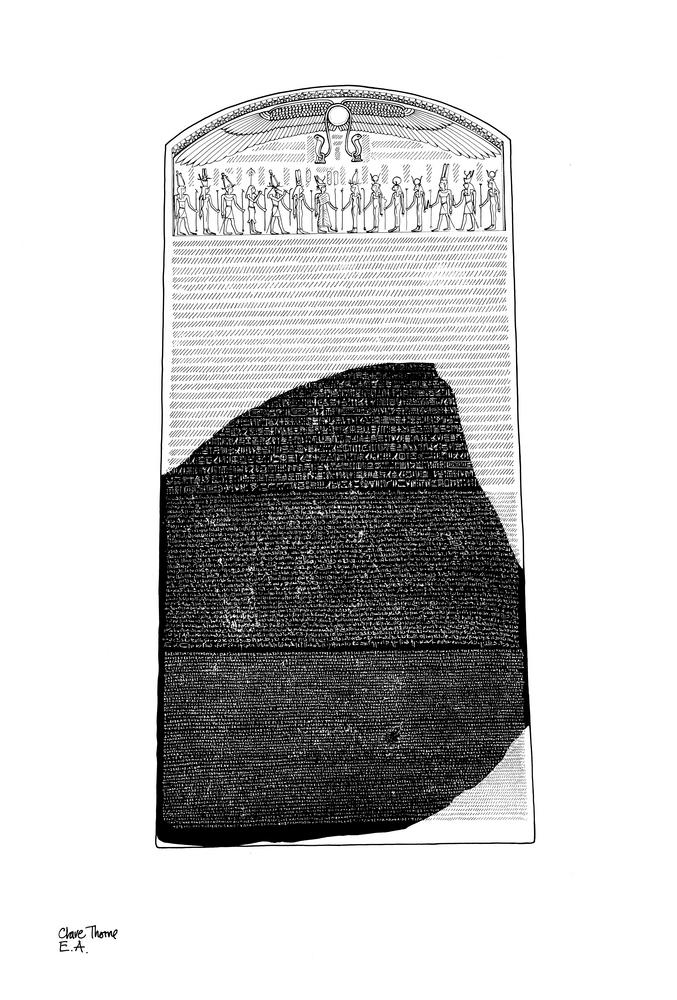

It was originally part of something called a "stele", a general term for an ancient monument set up to communicate something important.

A stele could be a grave, boundary, set of laws, or political announcement — several copies might be created and put up in different places.

A stele could be a grave, boundary, set of laws, or political announcement — several copies might be created and put up in different places.

The stele of which the Rosetta Stone was part had been made 196 BC by a group of priests to mark the coronation of Ptolemy V Epiphanes, King of Egypt.

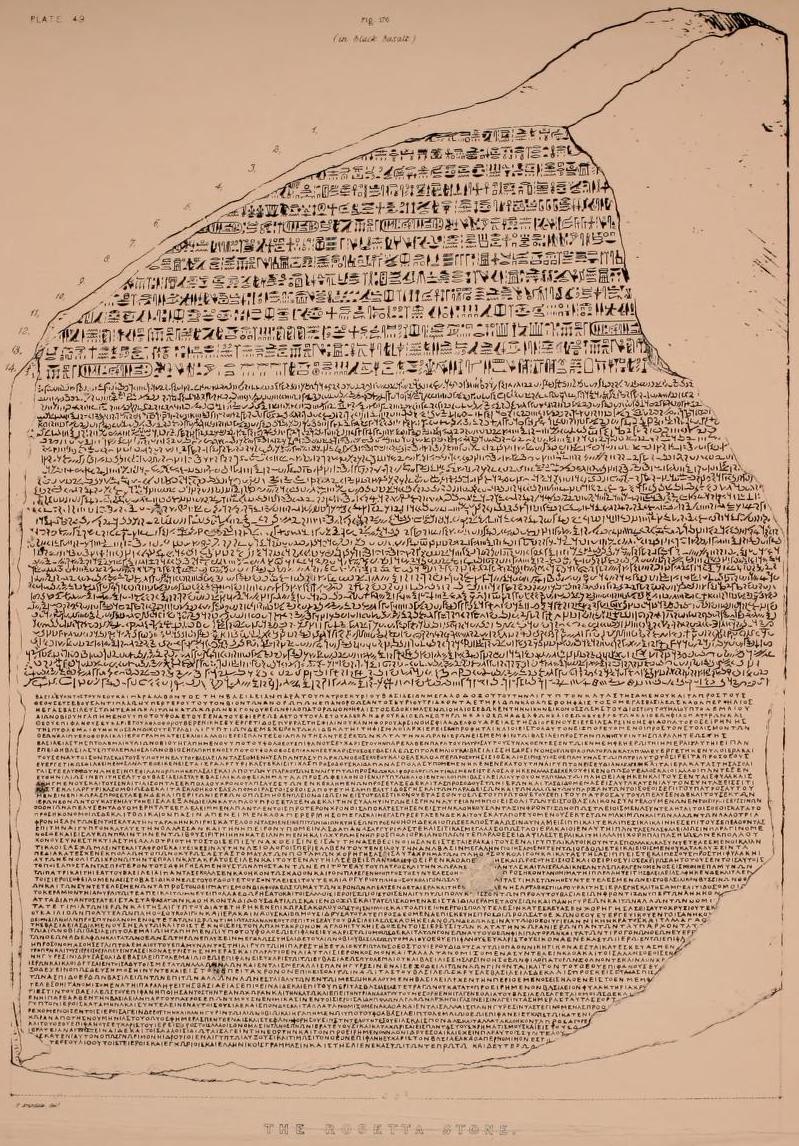

This decree was engraved in three scripts: Egyptian hieroglyphics, Egyptian Demotic, and Ancient Greek.

This decree was engraved in three scripts: Egyptian hieroglyphics, Egyptian Demotic, and Ancient Greek.

Such multilingual inscriptions aren't unusual.

Another example is the Behistun Inscription in Iran, made in about 500 BC for King Darius the Great of the Achaemenid Empire.

It was written in Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian, and played a major role in deciphering cuneiform.

Another example is the Behistun Inscription in Iran, made in about 500 BC for King Darius the Great of the Achaemenid Empire.

It was written in Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian, and played a major role in deciphering cuneiform.

So the purpose of the Ptolemaic stele had been to communicate an announcement regarding the new king, and to do so for a society that was both multicultural and multilingual.

See, Egypt had been invaded and conquered by Alexander the Great in 332 BC.

See, Egypt had been invaded and conquered by Alexander the Great in 332 BC.

After the end of Alexander's reign Egypt was taken over by one his generals, called Ptolemy — hence "Ptolemaic Egypt".

Ptolemy was a Macedonian Greek, and under his rule Egypt became increasingly Hellenised — thus the addition of a Greek version of the decree.

Ptolemy was a Macedonian Greek, and under his rule Egypt became increasingly Hellenised — thus the addition of a Greek version of the decree.

The second part of the story is how it was discovered.

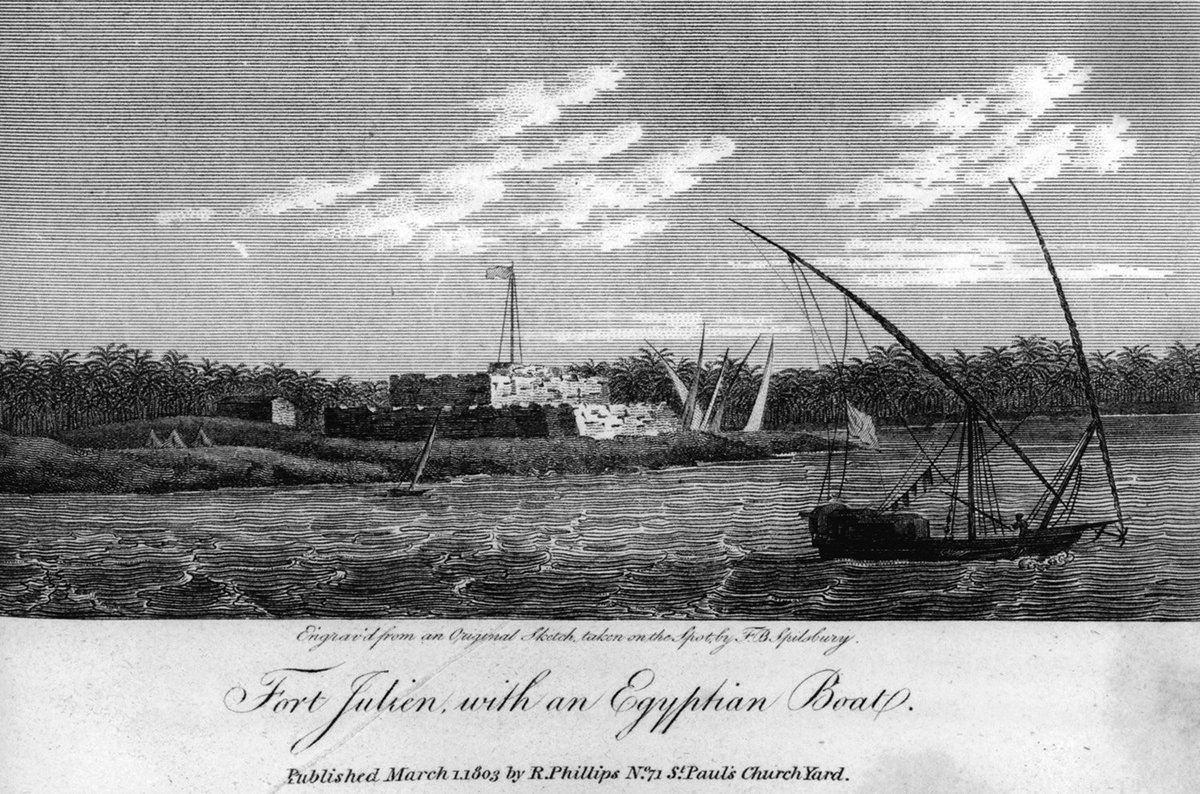

Under Sultan Qaitbay in the 1400s, during the Mamluk rule of Egypt, the stele was recycled — likely from another building rather than its original location — and used in the construction of a castle now called Fort Julien.

Under Sultan Qaitbay in the 1400s, during the Mamluk rule of Egypt, the stele was recycled — likely from another building rather than its original location — and used in the construction of a castle now called Fort Julien.

That sounds surprising, but in the past it was common to reuse bits of old buildings and ancient ruins — quality stone was expensive, after all.

This is called "spoliation" in architecture, like the columns at the Basilica Cistern in Istanbul, recycled from a former basilica:

This is called "spoliation" in architecture, like the columns at the Basilica Cistern in Istanbul, recycled from a former basilica:

In any case, the broken stele formed part of Fort Julien for centuries.

Until, in 1798, Napoleon invaded Egypt, which was then ruled by the Ottomans.

As part of this invasion Napoleon brought with him a team of scholars to investigate and document Egyptian history.

Until, in 1798, Napoleon invaded Egypt, which was then ruled by the Ottomans.

As part of this invasion Napoleon brought with him a team of scholars to investigate and document Egyptian history.

But it was a soldier — Lieutenant Pierre-François Bouchard — who made the discovery.

On 15th July 1799 he was at Fort Julien and, while part of the castle was being demolished, noticed a large stone covered in writing.

Bouchard reported this and the stone was saved.

On 15th July 1799 he was at Fort Julien and, while part of the castle was being demolished, noticed a large stone covered in writing.

Bouchard reported this and the stone was saved.

The British then defeated the French and took the Rosetta Stone — which had immediately been recognised as a profoundly important artefact — for themselves.

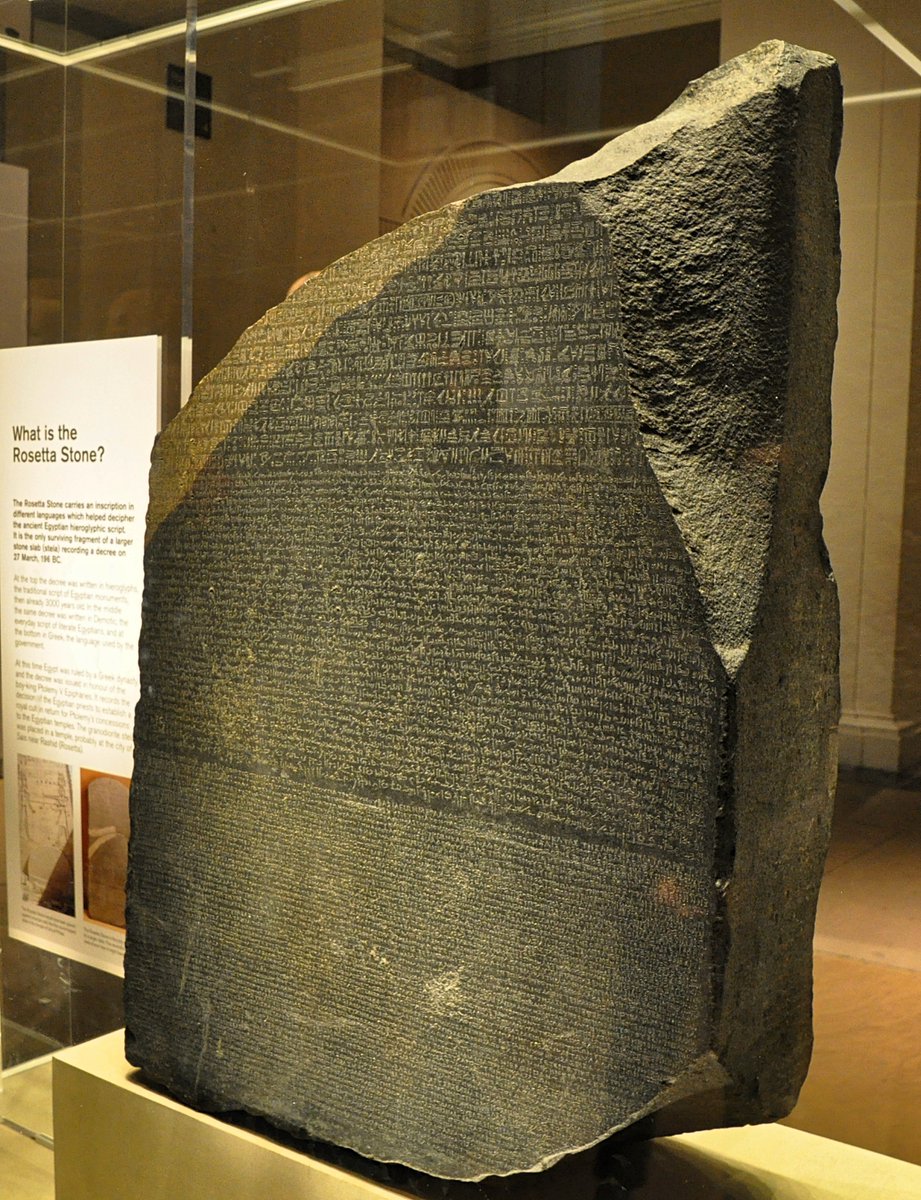

By 1802 it was in the British Museum, where it has remained ever since — despite Egyptian requests for repatriation.

By 1802 it was in the British Museum, where it has remained ever since — despite Egyptian requests for repatriation.

The third part of the story is how it changed history.

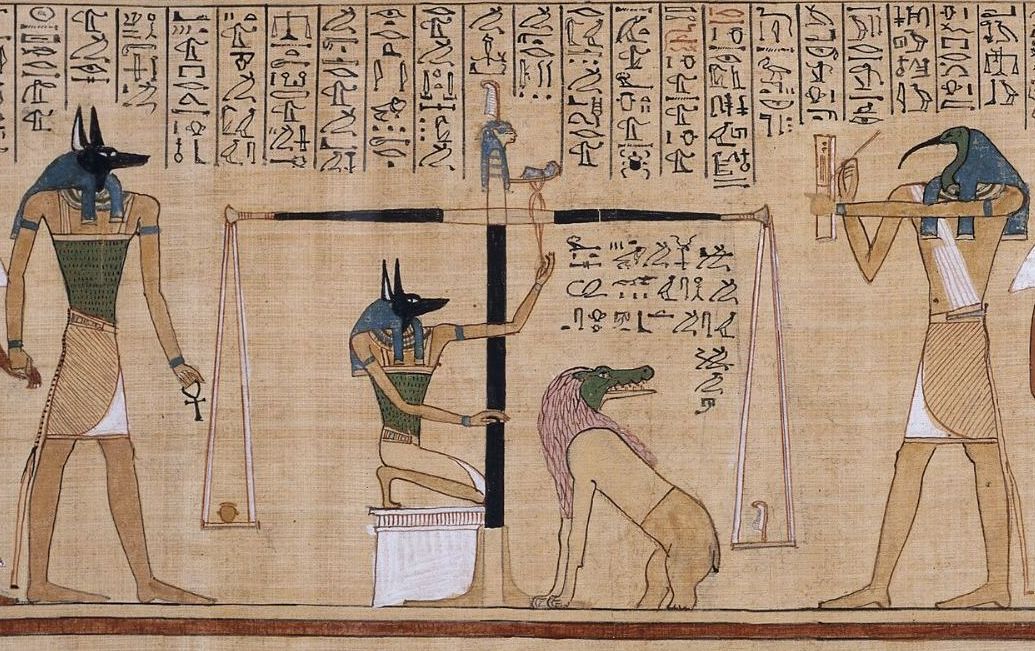

Ever since the Hellenisation of Egypt the use of hieroglyphics — invented over 2,000 years before — had been declining.

A process accelerated by the rise of Christianity and fall of the old Egyptian religion.

Ever since the Hellenisation of Egypt the use of hieroglyphics — invented over 2,000 years before — had been declining.

A process accelerated by the rise of Christianity and fall of the old Egyptian religion.

The last known inscription in hieroglyphics is called the Graffito of Esmet-Akhom, and was made in 394 AD.

Thereafter they melted from history — not only could nobody write hieroglyphics, but nobody could understand them either.

Masses of information were simply unavailable.

Thereafter they melted from history — not only could nobody write hieroglyphics, but nobody could understand them either.

Masses of information were simply unavailable.

So for centuries nobody could decipher these symbols that filled Ancient Egyptian ruins.

People simply had to speculate about what hieroglyphics were, and they became one of history's great mysteries — despite being the ancestor of the Latin, Cyrillic, and Arabic scripts.

People simply had to speculate about what hieroglyphics were, and they became one of history's great mysteries — despite being the ancestor of the Latin, Cyrillic, and Arabic scripts.

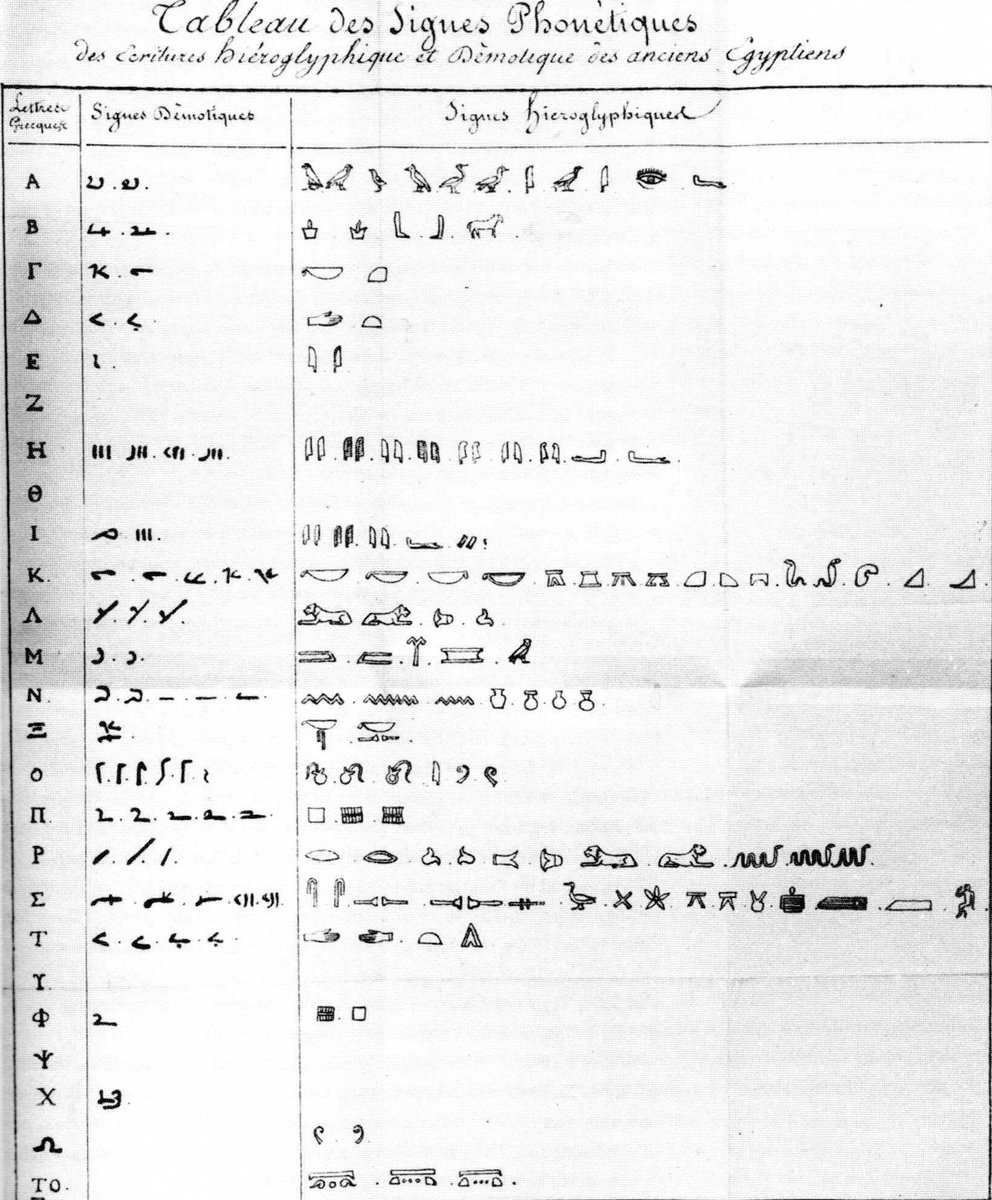

After the Rosetta Stone was discovered scholars around Europe threw themselves into deciphering hieroglyphics with the help of the Demotic and Greek inscriptions.

And in 1822 a Frenchman called Jean-François Champollion finally did it — although plenty more work followed later.

And in 1822 a Frenchman called Jean-François Champollion finally did it — although plenty more work followed later.

Thus Ancient Egypt was reawakened after millennia of slumber, and a whole chapter of human history — one of the earliest and most important in the world — was uncovered.

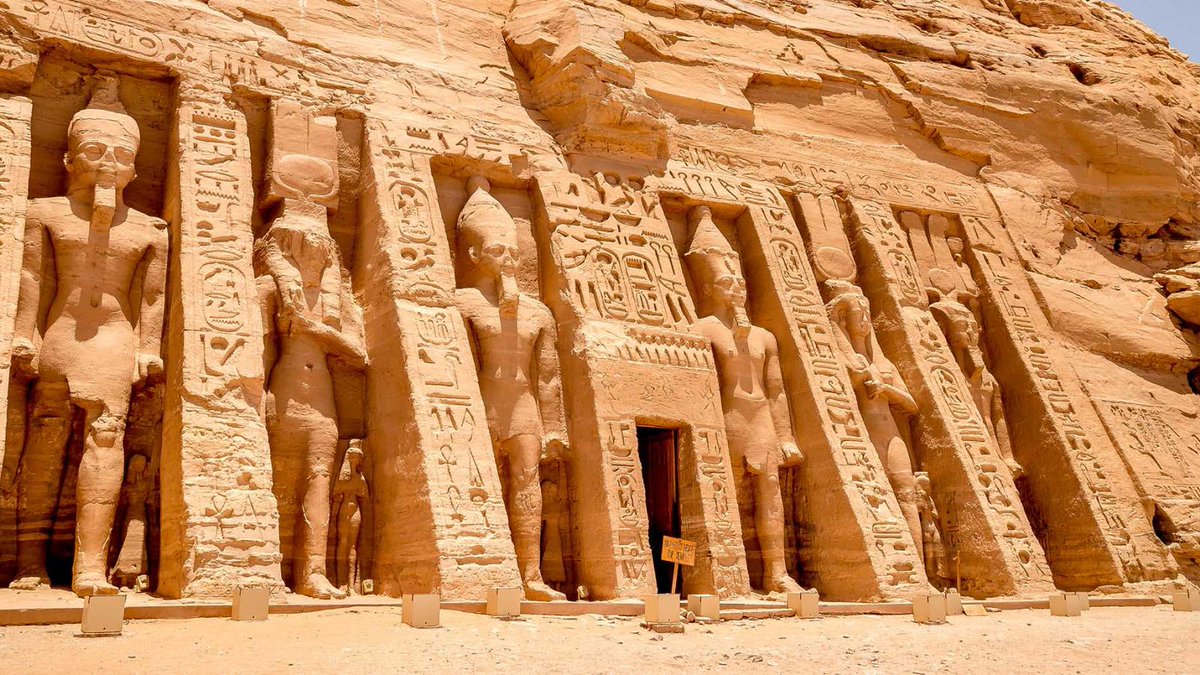

Hieroglyphics telling the history of Egypt, like these at Abu Simbel, spoke again at last.

Hieroglyphics telling the history of Egypt, like these at Abu Simbel, spoke again at last.

This, along with a host of other discoveries in Egypt, triggered a cultural movement known as "Egyptomania" in art, architecture, and design.

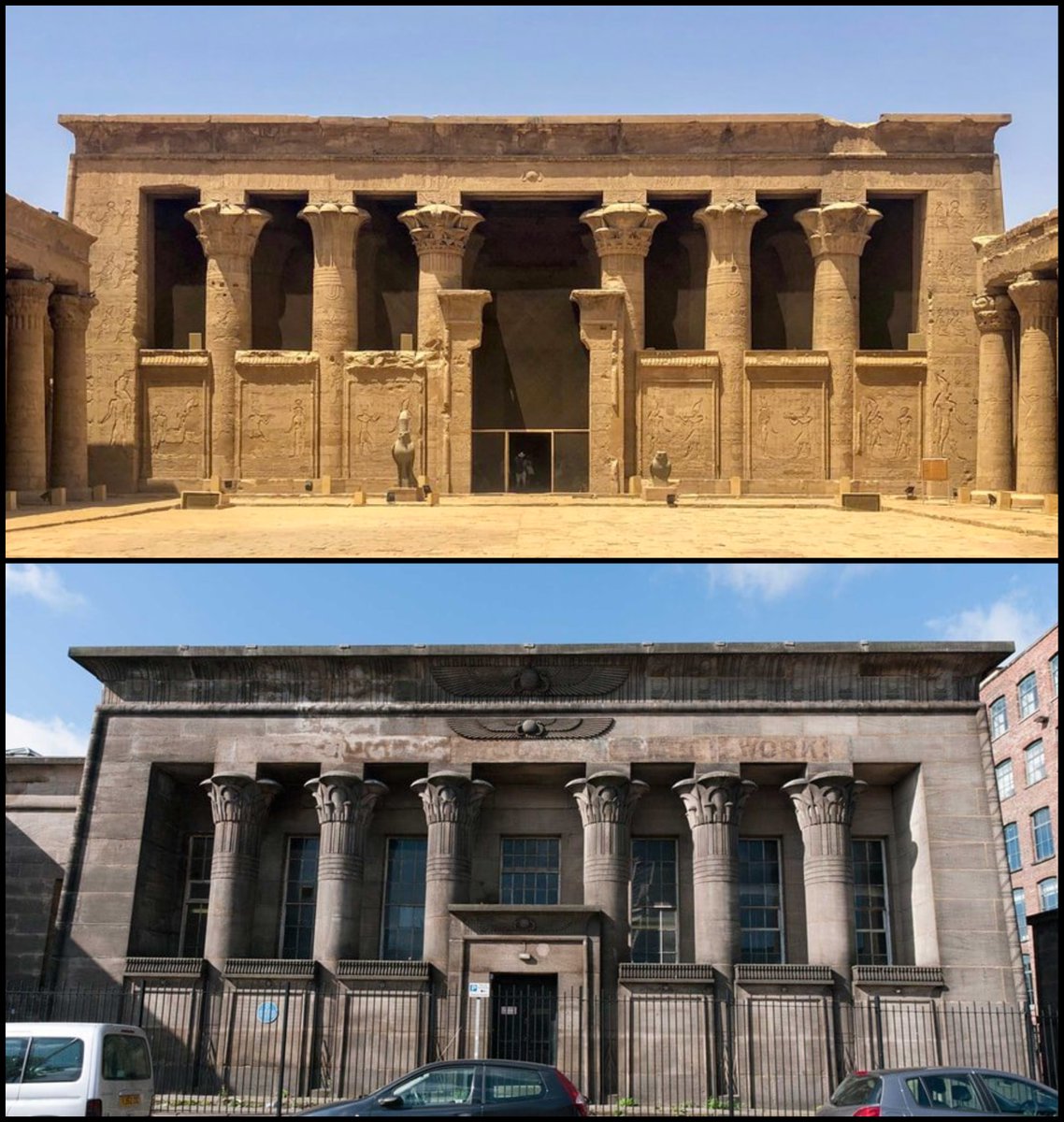

This old flax mill near Leeds, England — directly based on the Temple of Horus at Edfu — is just one example.

This old flax mill near Leeds, England — directly based on the Temple of Horus at Edfu — is just one example.

The final thing to say is that the Rosetta Stone is not totally unique — several other multilingual inscriptions, including hieroglyphics, have been discovered.

Such as the Philae obelisk, found in 1815, and the Decree of Canopus, found in 1866.

But the Rosetta was the first.

Such as the Philae obelisk, found in 1815, and the Decree of Canopus, found in 1866.

But the Rosetta was the first.

The story of the Rosetta Stone is interesting in itself, but also has broader relevance.

It shows that history is incredibly fragile — had it never been discovered (along with the other multilingual inscriptions) Ancient Egypt might have remained a mystery forever.

It shows that history is incredibly fragile — had it never been discovered (along with the other multilingual inscriptions) Ancient Egypt might have remained a mystery forever.

Who knows? There may come a day in the far future, when society and technology have changed enough, that English becomes a lost language — and perhaps even a day when the methods of accessing all our modern digitally-stored information are lost also.

It seems unimaginable, given how much data is created every day, that future generations might know little about the 21st century world.

But the Digital Dark Age is a real possibility — all these things we believe to be permanent could melt from history just like Egypt once did.

But the Digital Dark Age is a real possibility — all these things we believe to be permanent could melt from history just like Egypt once did.

In which case, one day, another "Rosetta Stone" might be discovered, some key that unlocks all the digitally-stored information we have created and opening a pathway into the long-lost 21st century.

And somebody in the far future might write something about that discovery too...

And somebody in the far future might write something about that discovery too...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh