Rembrandt, who lived 400 years ago, is usually called one of the greatest artists who ever lived.

But why? What made him so good?

Strange as it sounds, what made Rembrandt special was the way he painted himself — and how many times he did it...

But why? What made him so good?

Strange as it sounds, what made Rembrandt special was the way he painted himself — and how many times he did it...

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn was born in the Netherlands in 1606.

By 18 he was a painter, but unlike others of his generation he refused to study in Italy and remained at home.

At 22 he painted this brooding, supremely confident self-portrait — and a star was born.

By 18 he was a painter, but unlike others of his generation he refused to study in Italy and remained at home.

At 22 he painted this brooding, supremely confident self-portrait — and a star was born.

This was the Dutch Golden Age, a time of cultural and economic flourishing when the Netherlands found itself at the centre of global politics and its cities were booming with trade.

And, of course, an impossibly talented generation of artists like Vermeer and Rubens had arisen.

And, of course, an impossibly talented generation of artists like Vermeer and Rubens had arisen.

That was the context for Rembrandt's career.

He worked in Amsterdam and relied on private commissions — the Reformation meant artists no longer received commissions from the Church.

Hence his many portraits, like this one of a shipbuilder called Jan Rijcksen and his wife.

He worked in Amsterdam and relied on private commissions — the Reformation meant artists no longer received commissions from the Church.

Hence his many portraits, like this one of a shipbuilder called Jan Rijcksen and his wife.

These paintings of Dutch merchants, scholars, priests, and burghers give us a fabulous vision of life in the 17th century Netherlands — plus contemporary fashion, of lacy collars and dark robes.

As in this wedding portrait of Maerten Soolmans and Oopjen Coppit, from 1634.

As in this wedding portrait of Maerten Soolmans and Oopjen Coppit, from 1634.

The defining work of the Dutch Golden Age was painted by Rembrandt in 1642 — The Militia Company of District II under the Command of Captain Frans Banninck Cocq, better known simply as The Night Watch.

A group portrait that became the portrait of an entire era.

A group portrait that became the portrait of an entire era.

What made Rembrandt so good?

He was both prolific and versatile, an endlessly transforming artist who consistently produced paintings and prints in different styles and moods.

The Storm on the Sea of Galilee (1633) was his only seascape — it has been missing since 1990.

He was both prolific and versatile, an endlessly transforming artist who consistently produced paintings and prints in different styles and moods.

The Storm on the Sea of Galilee (1633) was his only seascape — it has been missing since 1990.

Rembrandt developed a sort of dramatic realism, and in combination with his natural sense of narrative he used it to craft compelling scenes like The Hundred Guilder Print, below.

This was far from the idealised beauty of Italian art or the gaudy work of other Baroque painters.

This was far from the idealised beauty of Italian art or the gaudy work of other Baroque painters.

But it is for this reason that he has also been criticised.

Some have said that his paintings, often bathed in shadow, are too austere and gloomy.

Others argue that his attraction to realism and plainness — rather than idealisation and beauty — can make his art rather bland.

Some have said that his paintings, often bathed in shadow, are too austere and gloomy.

Others argue that his attraction to realism and plainness — rather than idealisation and beauty — can make his art rather bland.

Some of those criticisms are probably fair, but it's worth remembering just how versatile Rembrandt was.

The Abduction of Europa, from 1632, shows his ability and willingness to embrace a more classical style — it is a shimmering, almost pearlescent masterpiece of Baroque art.

The Abduction of Europa, from 1632, shows his ability and willingness to embrace a more classical style — it is a shimmering, almost pearlescent masterpiece of Baroque art.

He was fascinated by light and made constant use of chiaroscuro — contrast between light and dark.

All his paintings and etchings have strong shadows, and are in some way defined by the glittering of light amidst shade.

Like his portrayal of Jeremiah:

All his paintings and etchings have strong shadows, and are in some way defined by the glittering of light amidst shade.

Like his portrayal of Jeremiah:

Or The Philosopher in Meditation, from 1632, where the whole scene is clad in heavy shadows and illuminated by the hazy, golden light of a window.

Rembrandt received endless praise for creating these sorts of realistic, incredibly dramatic atmospheric effects.

Rembrandt received endless praise for creating these sorts of realistic, incredibly dramatic atmospheric effects.

Rembrandt was also a talented landscape painter, whether as the subject or in the background.

He paid close attention to nature and made sure to depict trees, for example, as scrupulously as he could; his landscapes are often filled with gloriously knotted roots and trunks.

He paid close attention to nature and made sure to depict trees, for example, as scrupulously as he could; his landscapes are often filled with gloriously knotted roots and trunks.

But the majority of Rembrandt's work, in all mediums, depicted stories from the Bible.

Belshazzar's Feast from 1635, his first major biblical scene, is probably his most famous.

Some love it, but some have called this sort of thing boring and drably realistic.

Belshazzar's Feast from 1635, his first major biblical scene, is probably his most famous.

Some love it, but some have called this sort of thing boring and drably realistic.

Unsurprisingly, Rembrandt became an immediate superstar and remained one, with admirers and collectors all over Europe — a status that has never since declined.

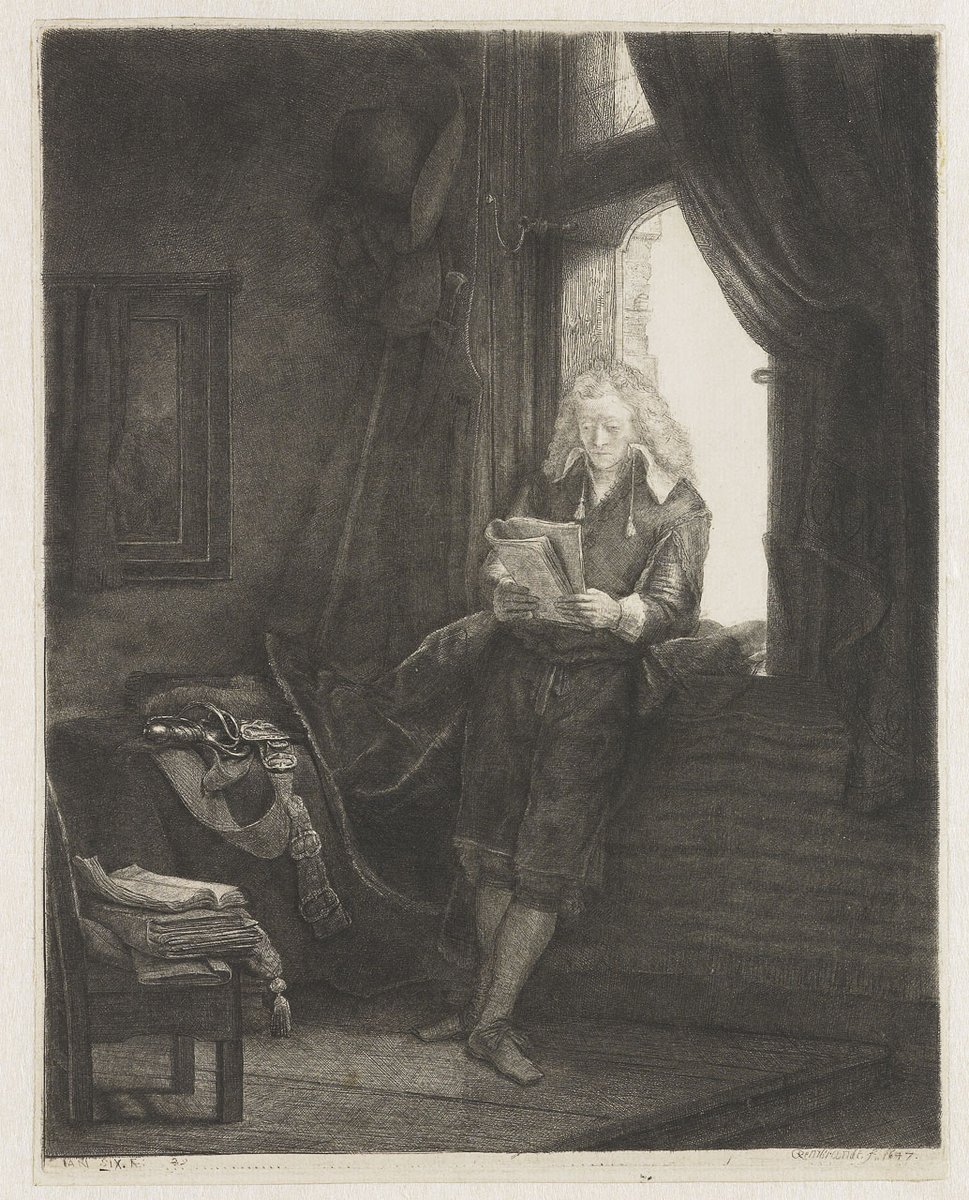

His etchings in particular — with their unusual, illustrative, wonderfully expressive style — were wildly popular.

His etchings in particular — with their unusual, illustrative, wonderfully expressive style — were wildly popular.

But what was the crowning achievement of his career?

Well, Rembrandt painted and etched dozens of self-portraits over the course of more than forty years, and collectively they form the most intimate and revealing visual biography of pretty much any historical figure.

Well, Rembrandt painted and etched dozens of self-portraits over the course of more than forty years, and collectively they form the most intimate and revealing visual biography of pretty much any historical figure.

The self-portrait was already an established genre, and there was even a fashion in the Netherlands for buying the self-portraits of famous artists.

But the self-portrait as we think of it now — an intimate, expressive work of art — was not a thing... until Rembrandt came along.

But the self-portrait as we think of it now — an intimate, expressive work of art — was not a thing... until Rembrandt came along.

Looking through his dozens of portraits you can see the changing expressions of a precocious youth who became a world-weary, though still witty, old man.

His early self-portraits, like this one from 1630, are bursting with creative ecstasy.

His early self-portraits, like this one from 1630, are bursting with creative ecstasy.

Then, at the outset of his career and once his star had already risen, we find self-portraits full of confidence and swagger:

Throughout we see a steady maturing, both of the man himself and the artist.

In this self-portait from 1640 you can see that the youthful excess has started to melt away, replaced by something like a calm, self-conscious melancholy.

Although, as ever, the confidence is there.

In this self-portait from 1640 you can see that the youthful excess has started to melt away, replaced by something like a calm, self-conscious melancholy.

Although, as ever, the confidence is there.

Rembrandt's life became difficult in the 1650s, as recession hit Amsterdam and, after selling all his paintings, he was bankrupted.

This, along with personal tragedy and a gentle fading of his popularity, took its toll.

Here, in 1665, you can see it in his eyes.

This, along with personal tragedy and a gentle fading of his popularity, took its toll.

Here, in 1665, you can see it in his eyes.

His self-portait drawings and etchings are particularly expressive, some of them funny and some remarkably modern.

Rembrandt looked at himself with a rare composure, and in an age now when we look at our own faces more than ever, there is much we could learn from how he did so.

Rembrandt looked at himself with a rare composure, and in an age now when we look at our own faces more than ever, there is much we could learn from how he did so.

His self-portraiture is matched only by the likes of Vincent van Gogh and Frida Kahlo, as the total vision of a human being across their life.

Rembrandt was eternally and shamelessly inquisitive about himself, introspective in a Shakespearean way.

"Who am I?" he kept asking.

Rembrandt was eternally and shamelessly inquisitive about himself, introspective in a Shakespearean way.

"Who am I?" he kept asking.

It is this unusual character that defines all his work, whether Biblical scenes or self-portraits, and through Rembrandt's art we come to know this strong, contemplative, striking personality.

Does he deserve the praise he gets? Surely... but what would Rembrandt say himself?

Does he deserve the praise he gets? Surely... but what would Rembrandt say himself?

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh