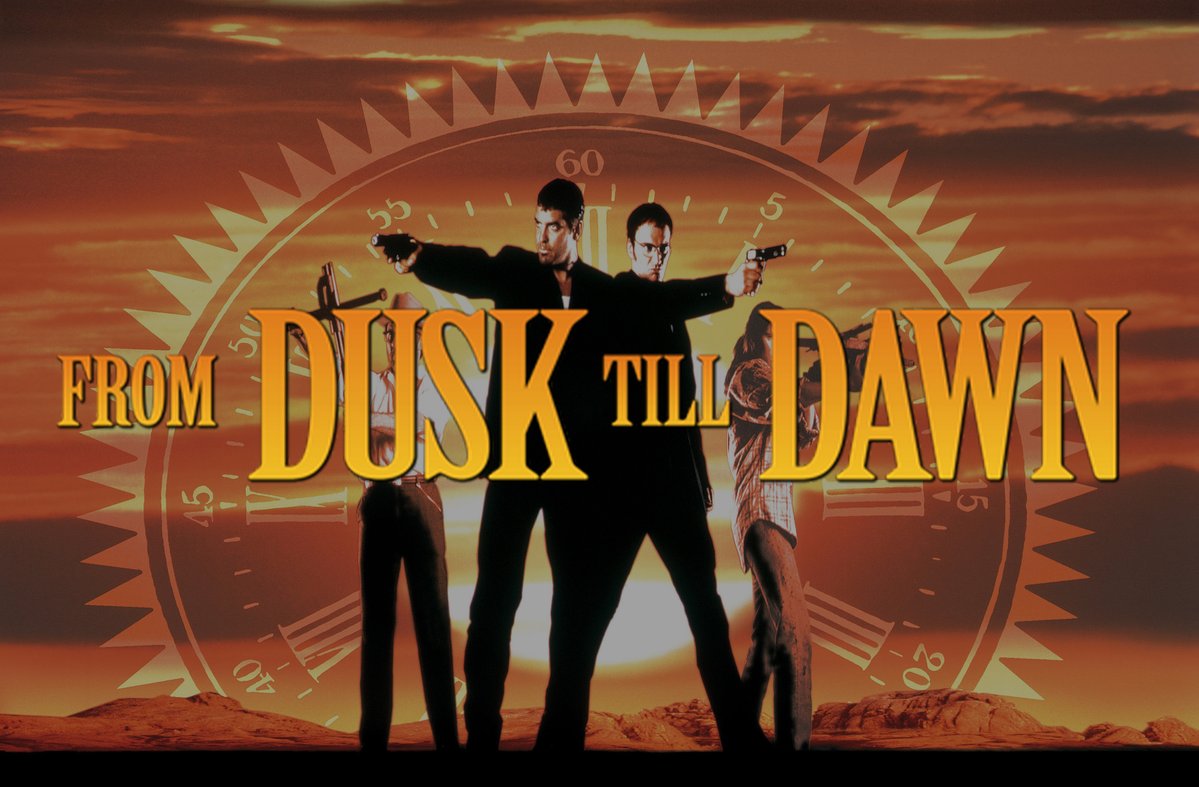

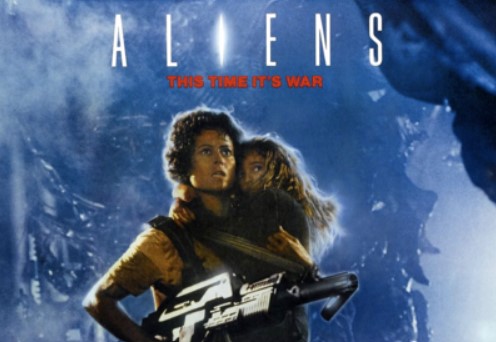

ALIENS was released 38 years ago this week. Acclaimed as one of the great action movies and best sequels ever made, the making of story is like being on an express elevator to hell… going down…

1/51

1/51

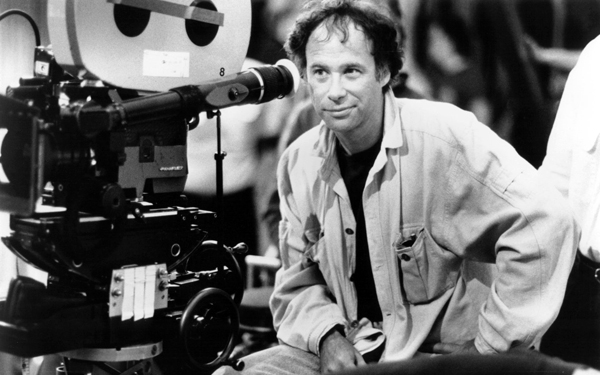

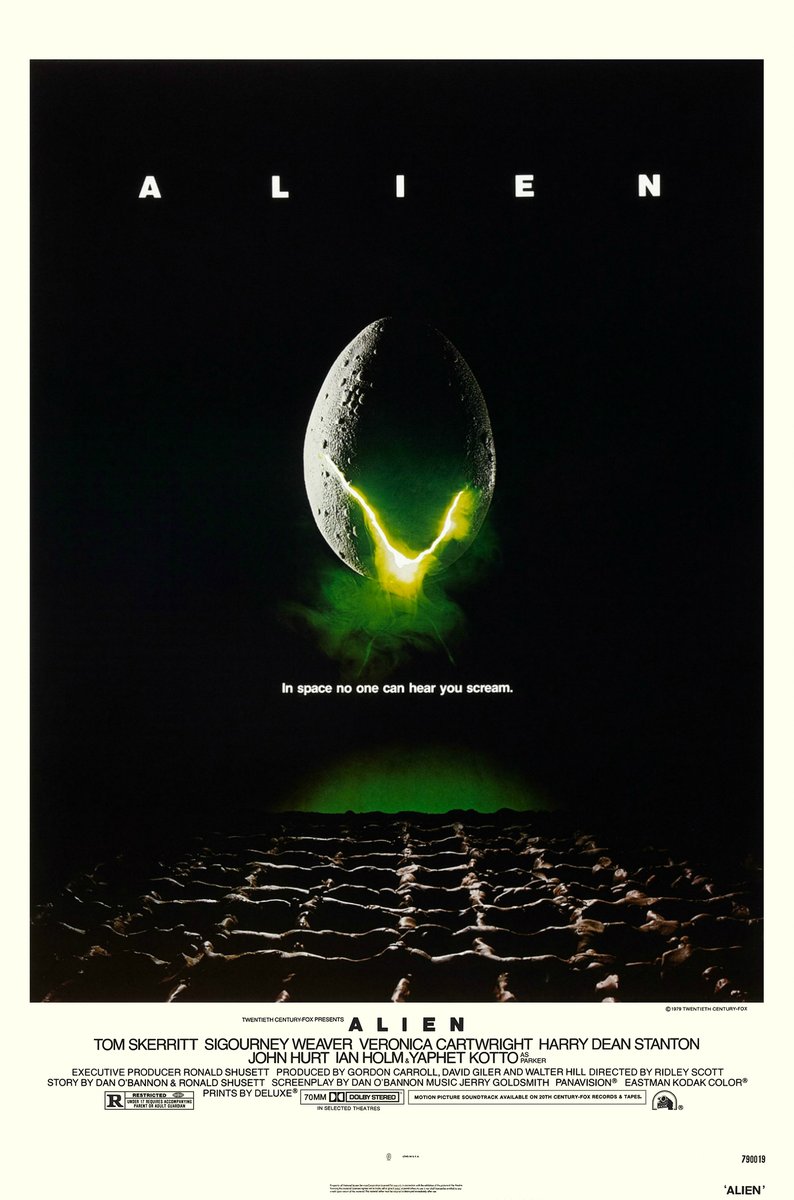

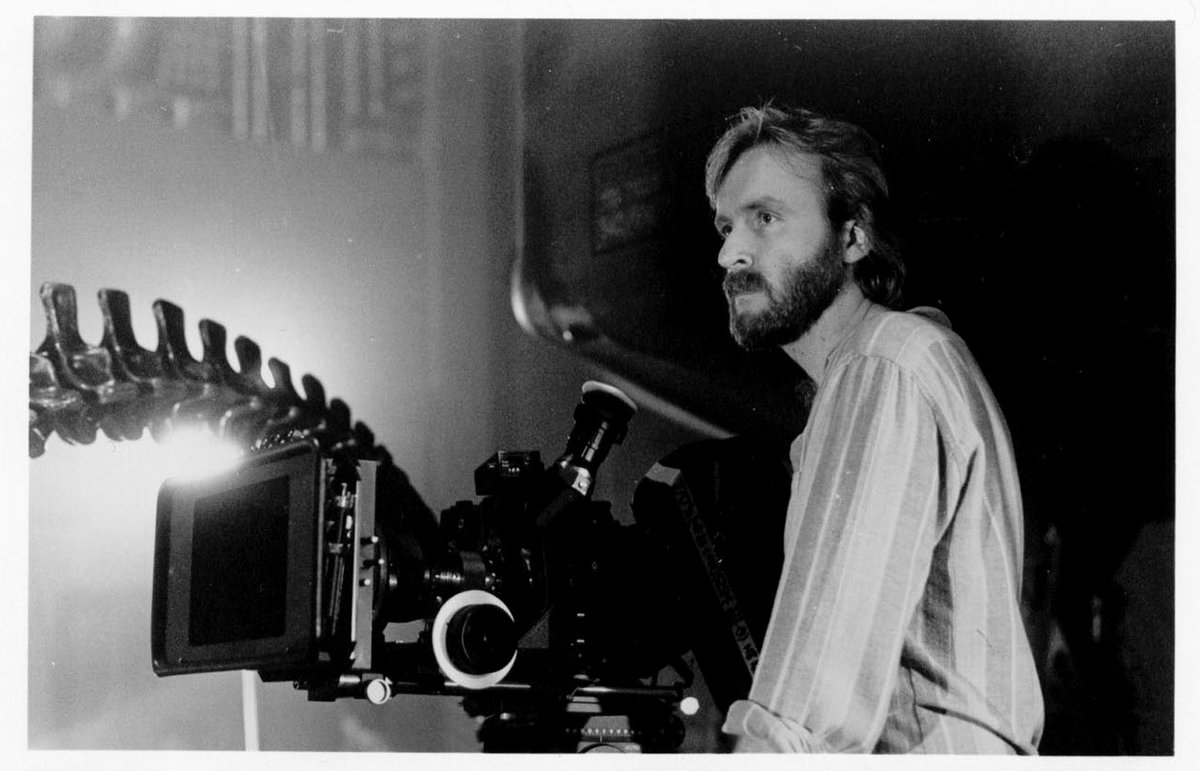

With the success of Alien, 20th Century Fox were keen on a sequel but it was delayed until 1983. At that time, James Cameron was sending his script for The Terminator to studios to find writing work. Fox read it and liked it.

2/51

2/51

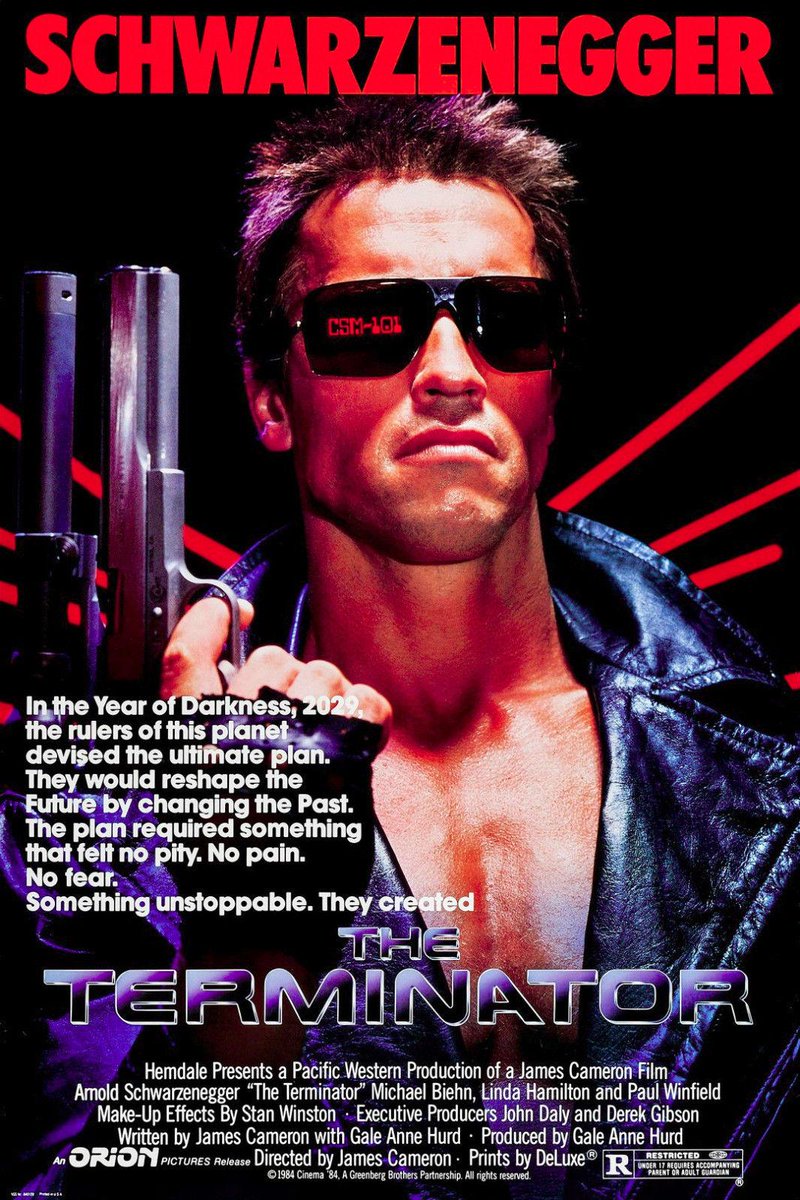

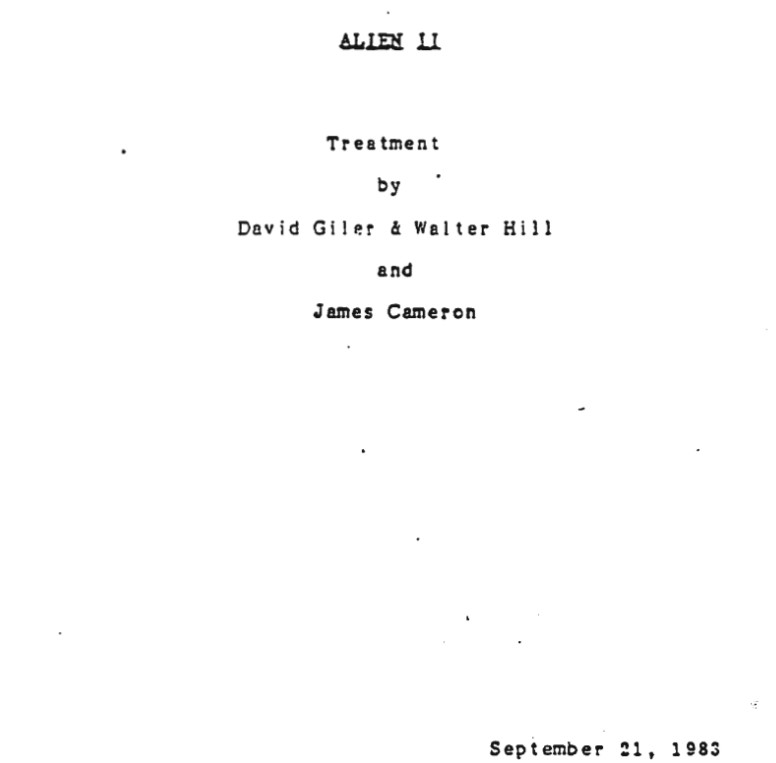

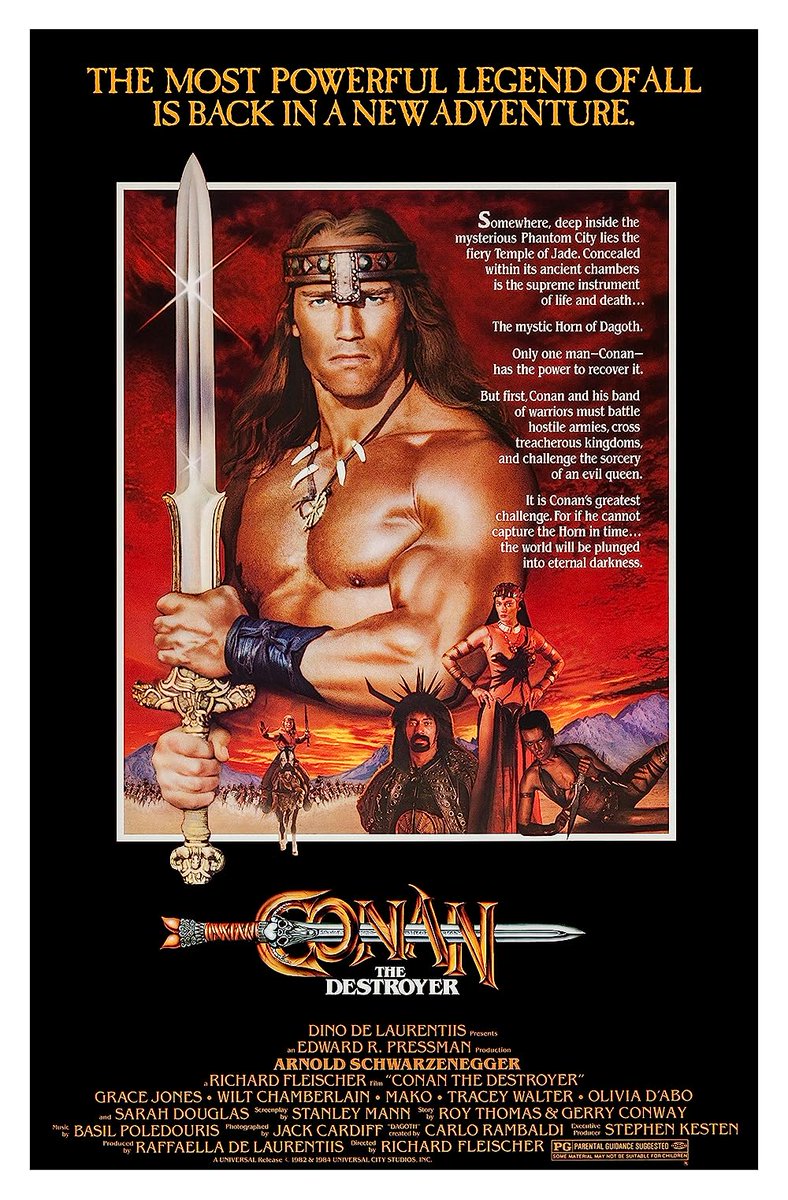

Cameron wrote a treatment called Alien II but didn’t have time to write the script. However, The Terminator was delayed 9 months because Arnold Schwarzenegger had an obligation to make Conan the Destroyer, so Cameron finished Aliens.

3/51

3/51

Then, after The Terminator was released in 1984 to a fantastic response, the studio hired Cameron to direct Aliens as well. In a now-legendary moved in Cameron’s pitch to Fox he wrote ‘Alien’ on a board and then amended it to say ‘Alien$’.

4/51

4/51

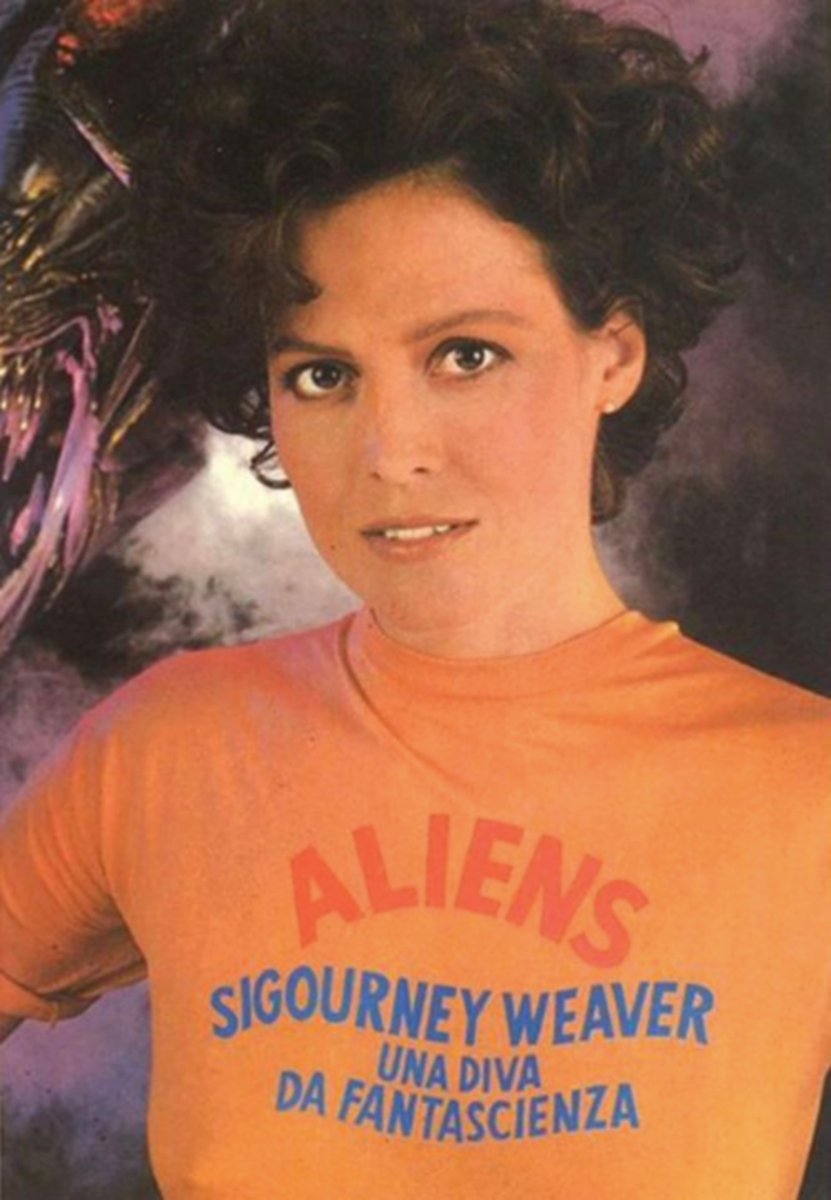

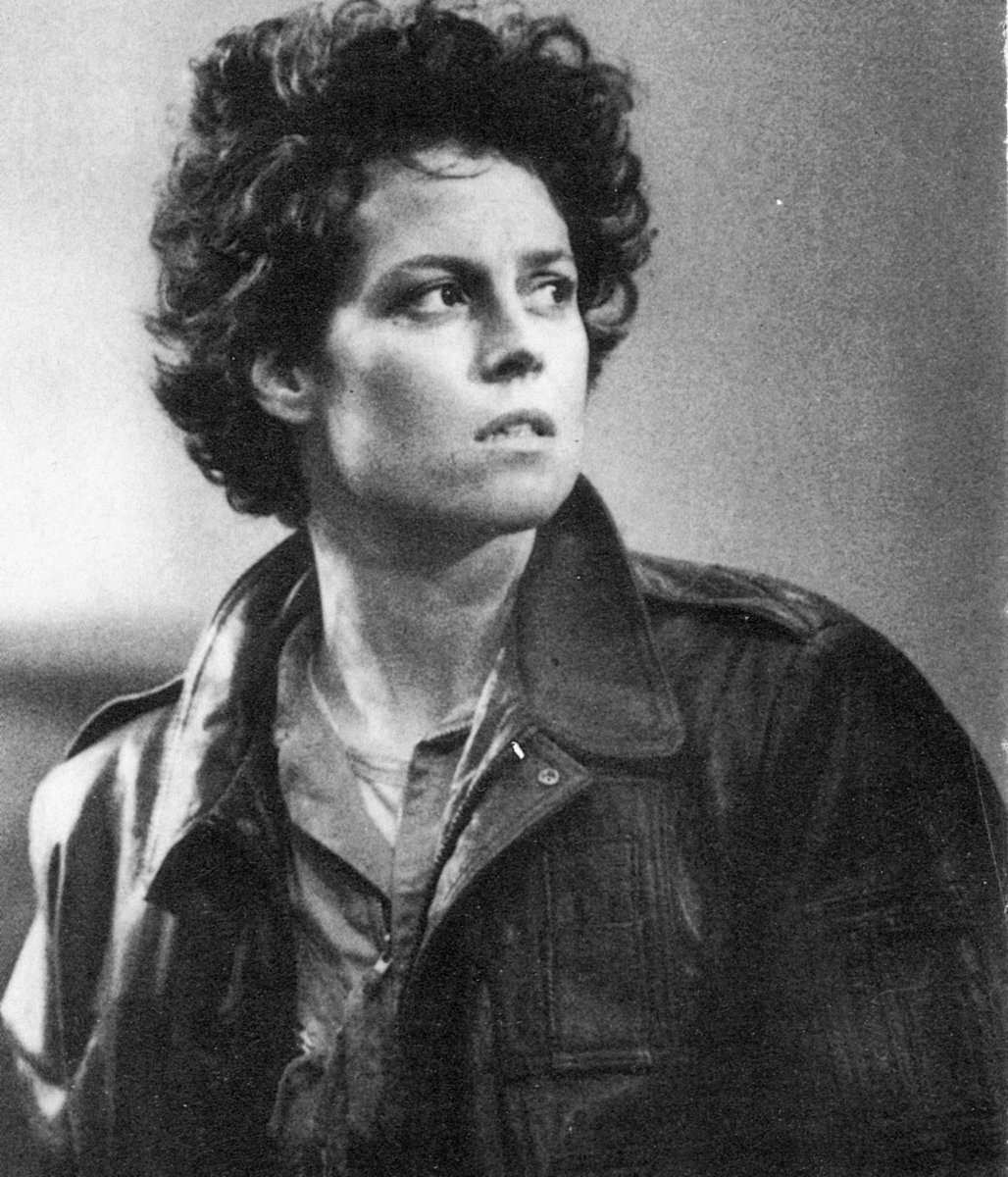

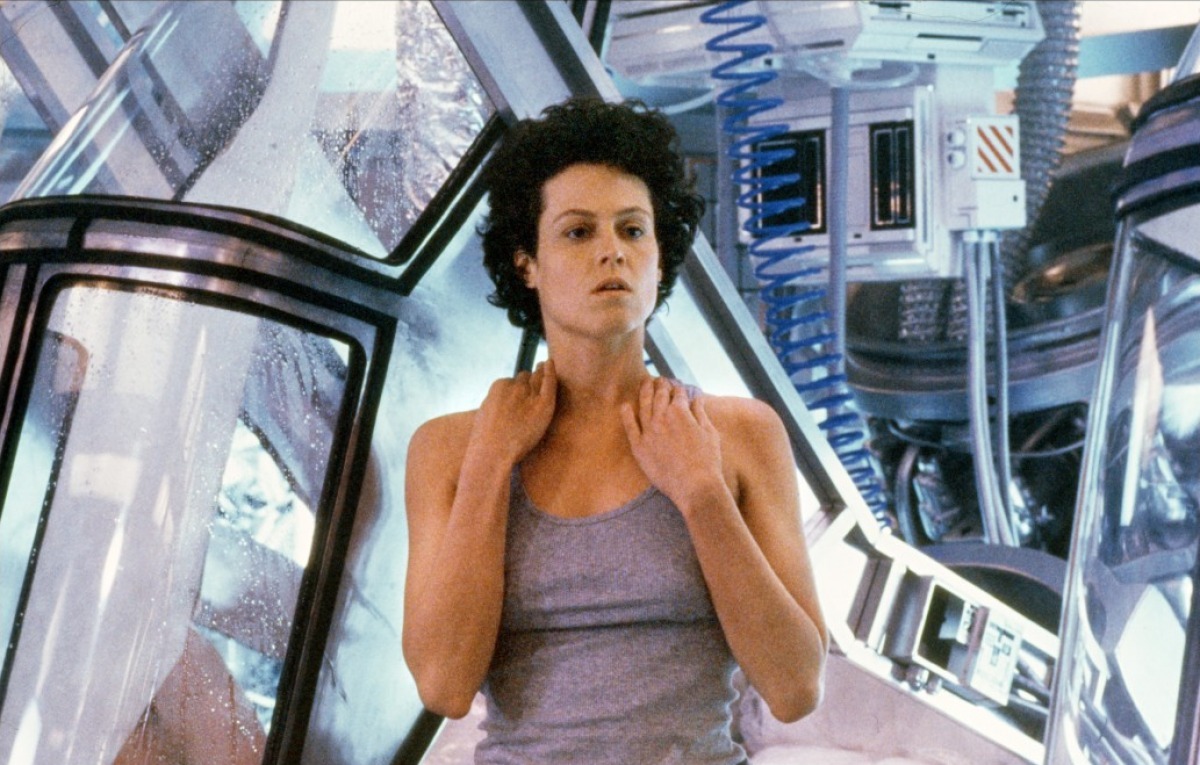

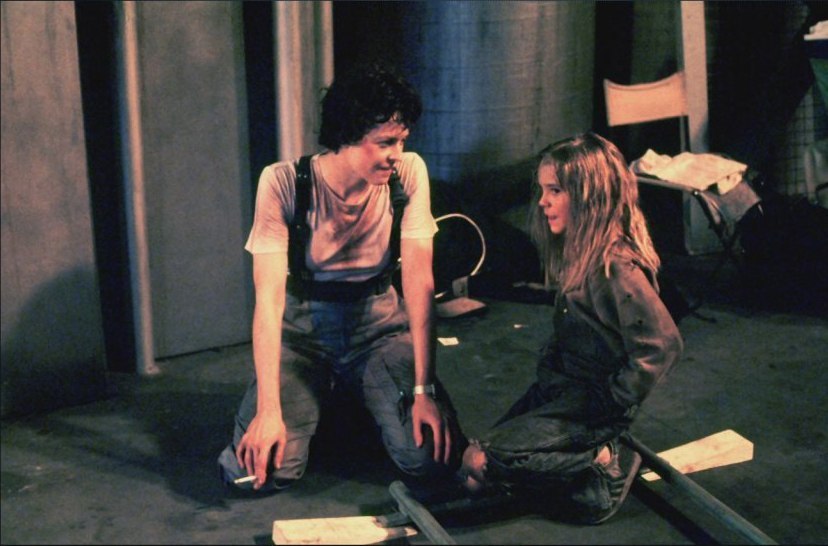

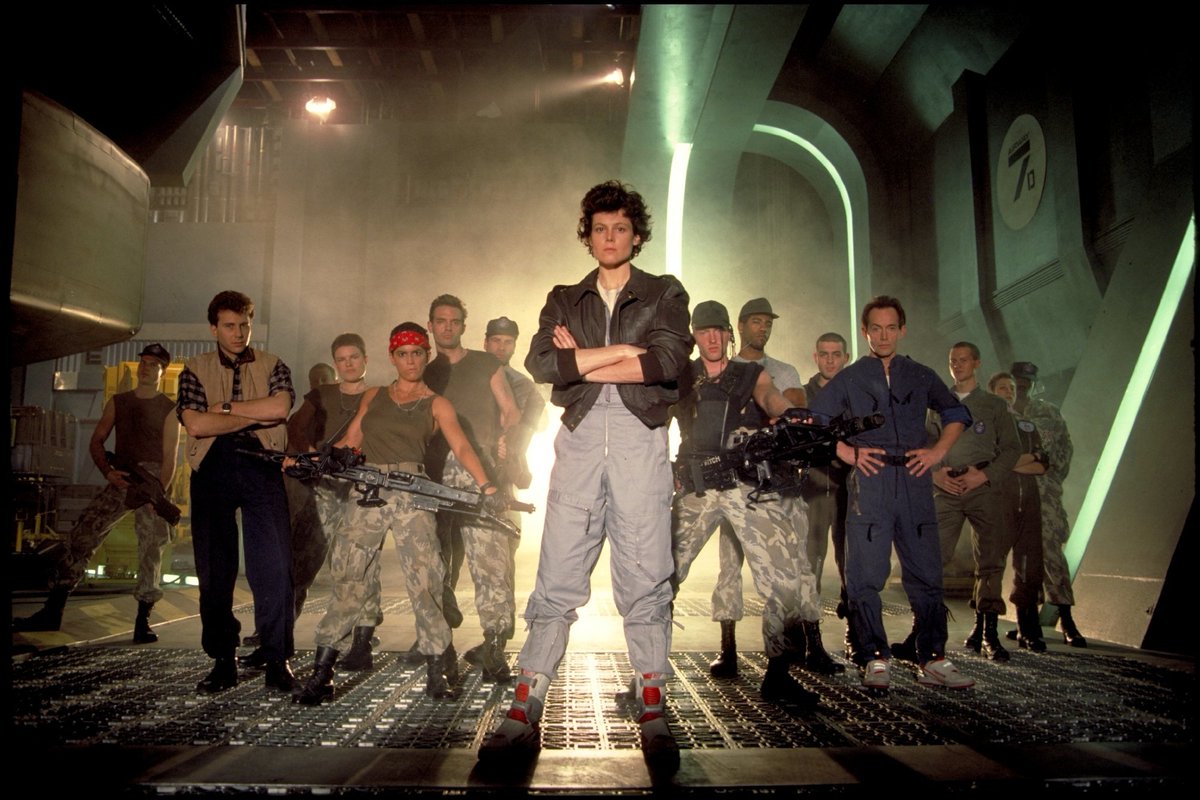

Sigourney Weaver had already rejected offers from Fox to do Alien sequels, thinking Ripley would be poorly written. Then she read James Cameron’s script. She was impressed with the quality of Cameron’s writing, and loved the mother-daughter bond between Ripley and Newt.

5/51

5/51

Weaver was paid $35,000 for Alien but that film and Ghostbusters had made her a huge star: she wanted $1m for Aliens, which the studio refused to pay. Cameron was desperate to have her on board, so Fox relented, and Weaver signed on for a $1m fee.

6/51

6/51

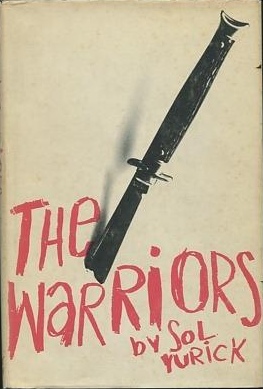

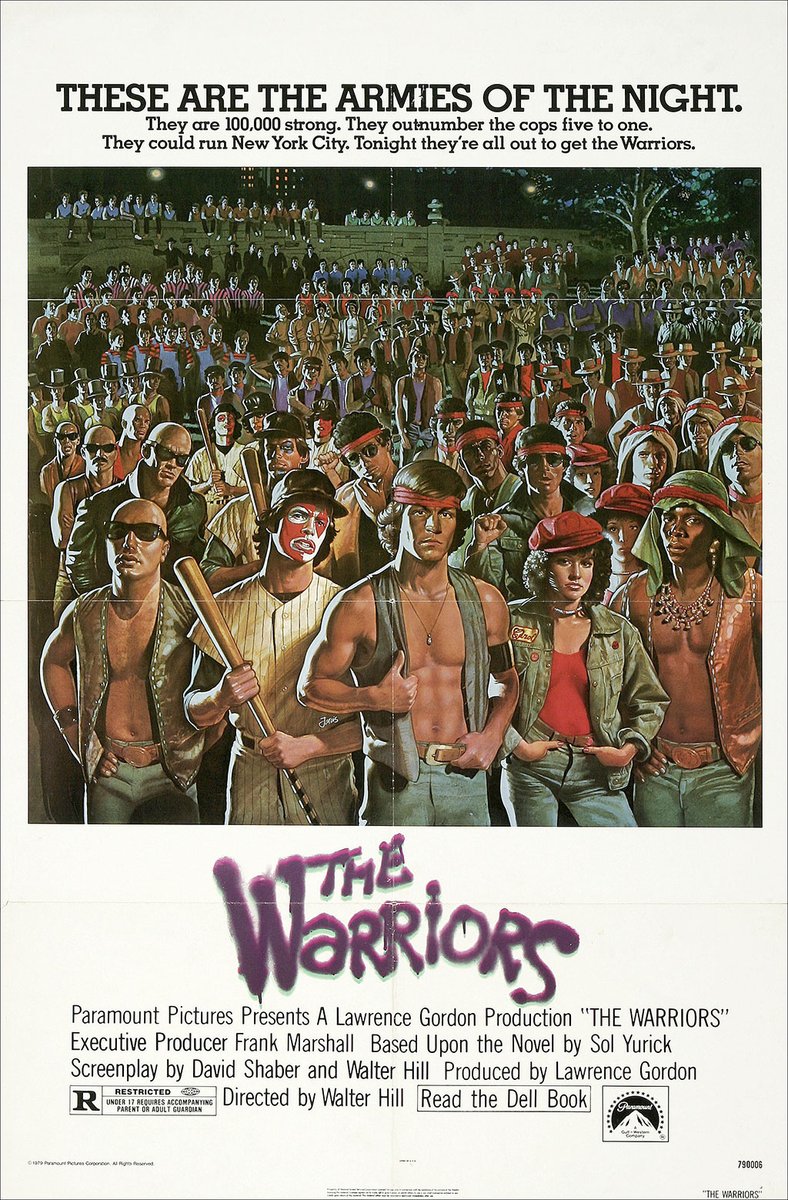

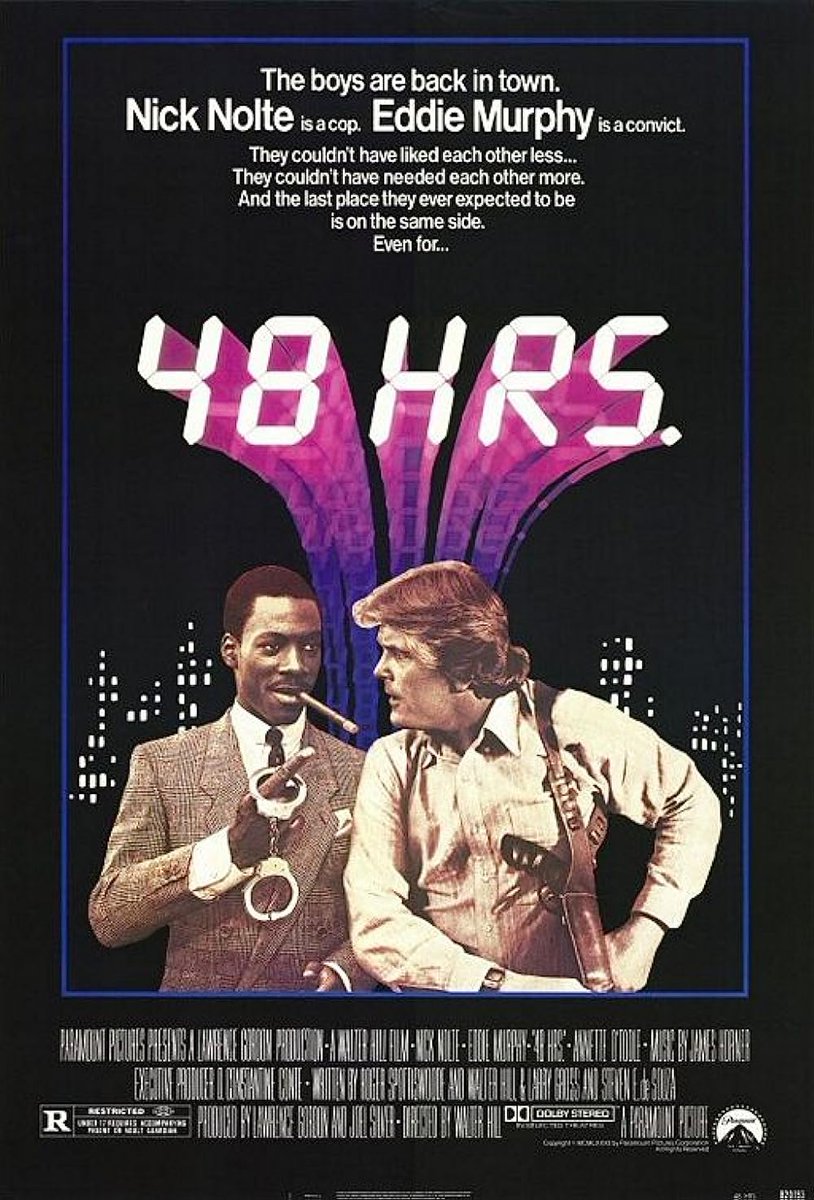

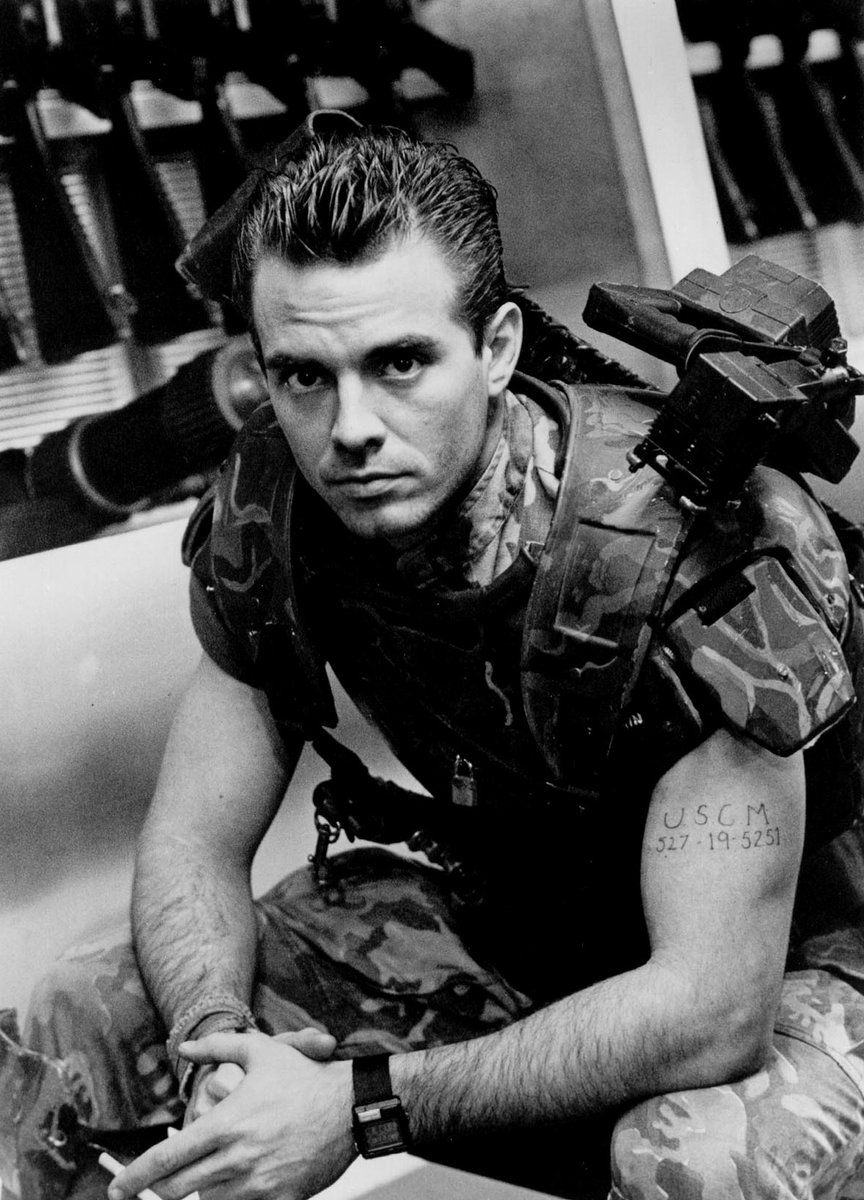

The part of Hicks went to James Remar who had starred in The Warriors and 48 Hrs. Both of those films were directed by Walter Hill, so there was a connection. Only a few days into shooting though, Remar was fired by Cameron.

7/51

7/51

The studio put Remar’s departure down to artistic differences but years later Remar admitted it was because he had a drug problem, and had been caught on-set with a bag of cocaine. In the scene where the marines enter the alien nest, there is a shot of Remar as Hicks.

8/51

8/51

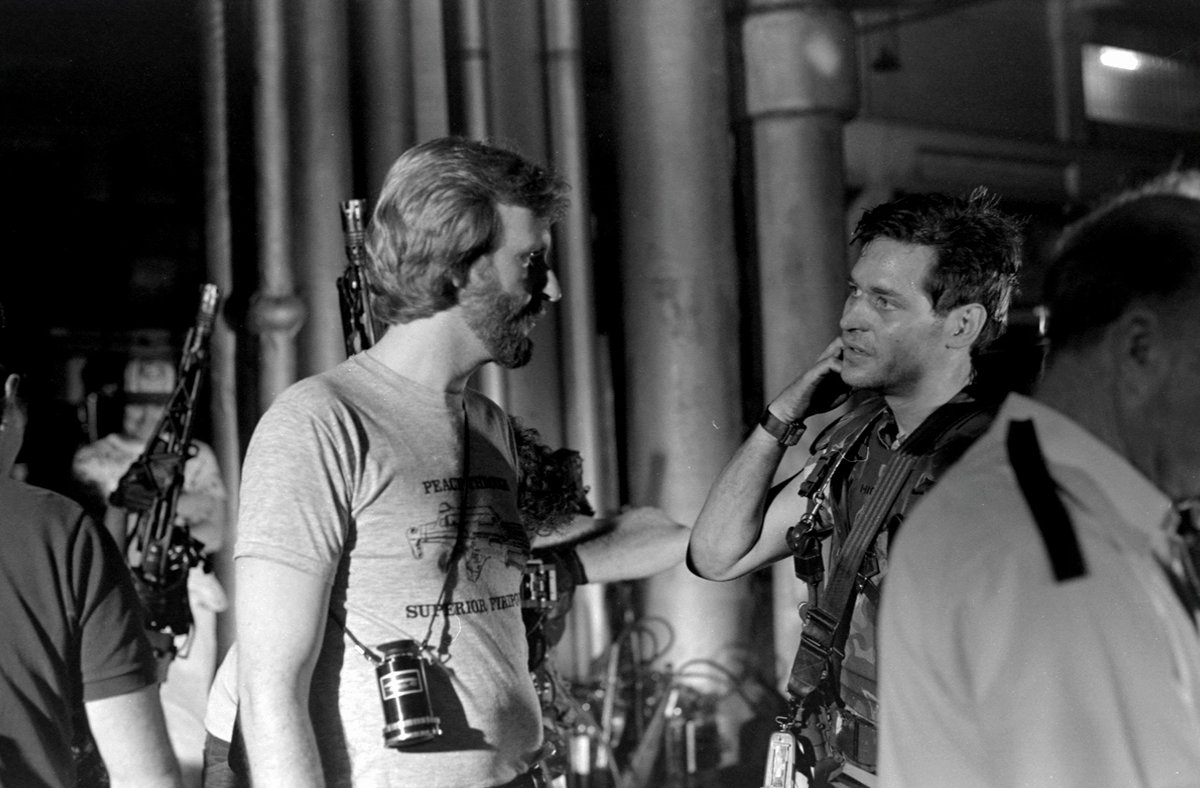

Having just worked with Michael Biehn on The Terminator, Cameron told the studio that was who he wanted to replace Remar. Biehn was flown in immediately to re-shoot Remar’s scenes, 1 week after everybody else started shooting.

9/51

9/51

Cameron wanted an unknown actress as Newt. Casting agents scouted schools in England and discovered Carrie Henn at a school in Lakenheath. Though she lacked acting experience, she didn’t smile after every line like other auditionees who had experience working on TV ads.

10/51

10/51

Bill Paxton and Cameron had worked together on The Terminator and Paxton was very ken to be in Aliens. Cameron got him in to audition and Fox knew him from Weird Science, so he was cast as Hudson.

11/51

11/51

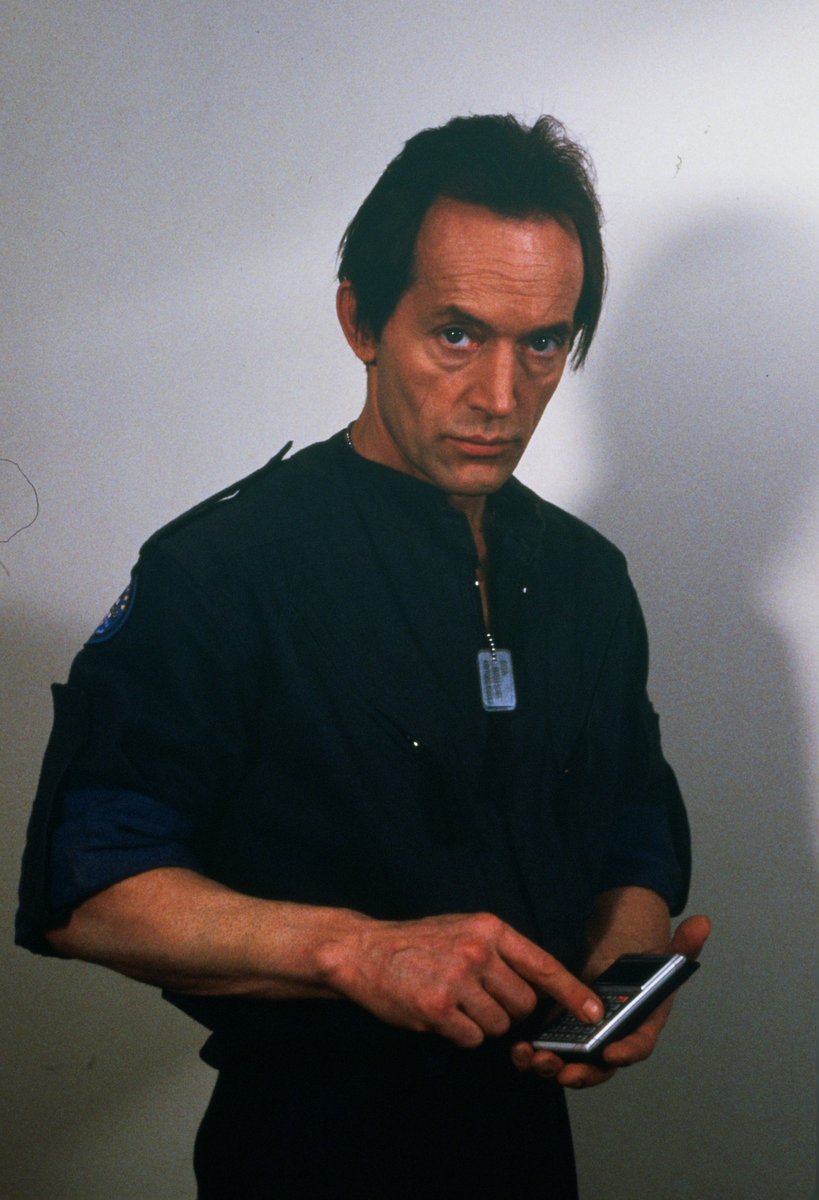

Cameron had almost cast Lance Henriksen as The Terminator, and always wanted him as loyal android, Bishop. Henriksen wanted to differentiate himself from Ash, the android in Alien, so suggested he wear contact lenses, but Cameron vetoed the idea.

12/51

12/51

Hudson asks Vasquez (Jenette Goldstein) if she’s been mistaken for a man and she says “No, have you?” Cameron took it from a story about 1930s icon Tallulah Bankhead. A columnist said to her “Have you ever been mistaken for a man?” and she replied “No, darling. Have you?”

13/51

13/51

Weaver asked for changes to the script, many of which Cameron accommodated. Reportedly though, there was one Cameron wouldn’t acquiesce too – Weaver requested Ripley not fire a gun in the film.

14/51

14/51

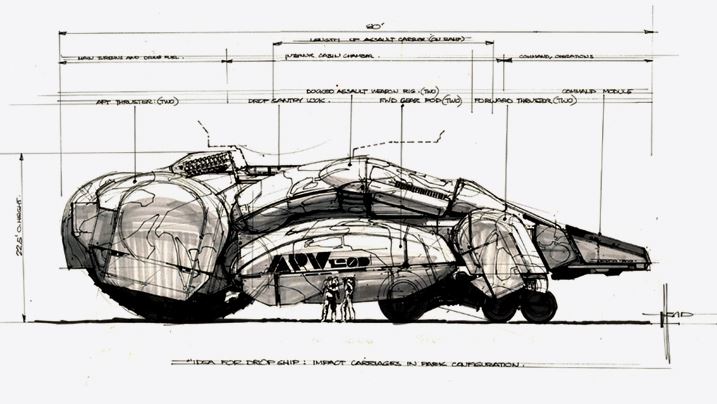

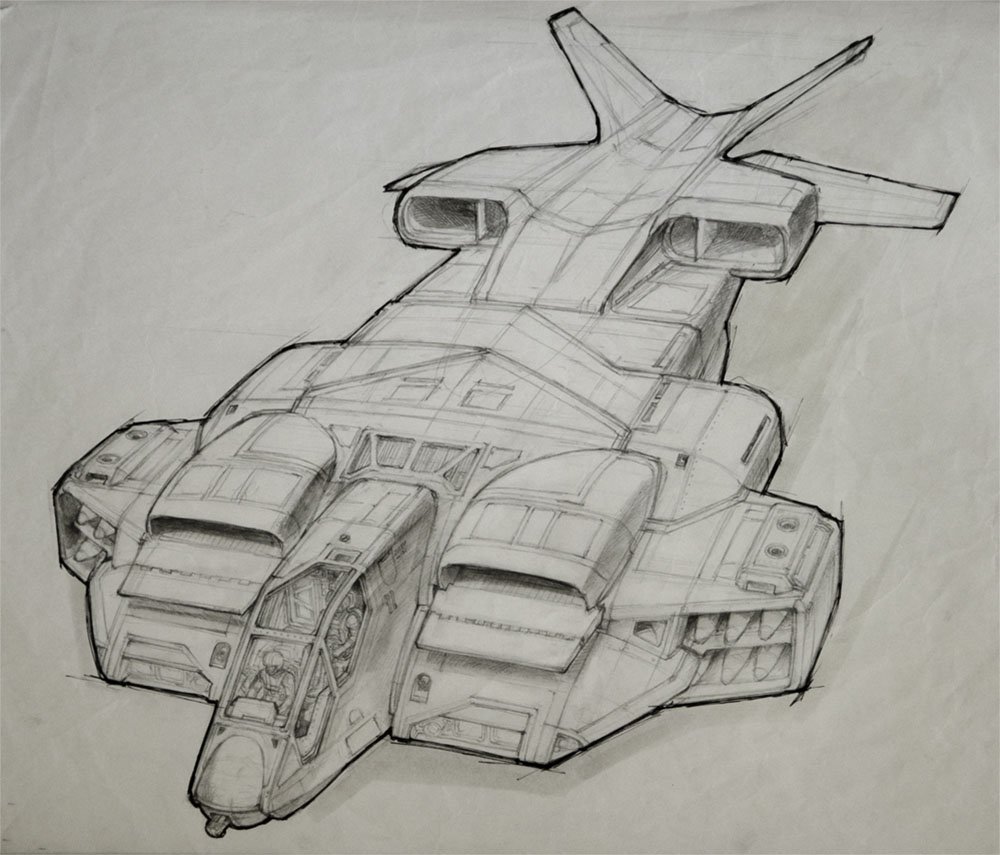

Aesthetically, Cameron was inspired by the Vietnam War. The way the marines look and talk is reminiscent of Vietnam movies. And the drop ship was based on the look of an Apache helicopter.

15/51

15/51

Cameron had the actors personalise their own suits of armour like marines in Vietnam. Hudson has “Louise” written on his (the name of Paxton’s wife). Dietrich has “Blue Angel” written on her helmet, a nod to the 1930 film The Blue Angel, starring Marlene Dietrich.

16/51

16/51

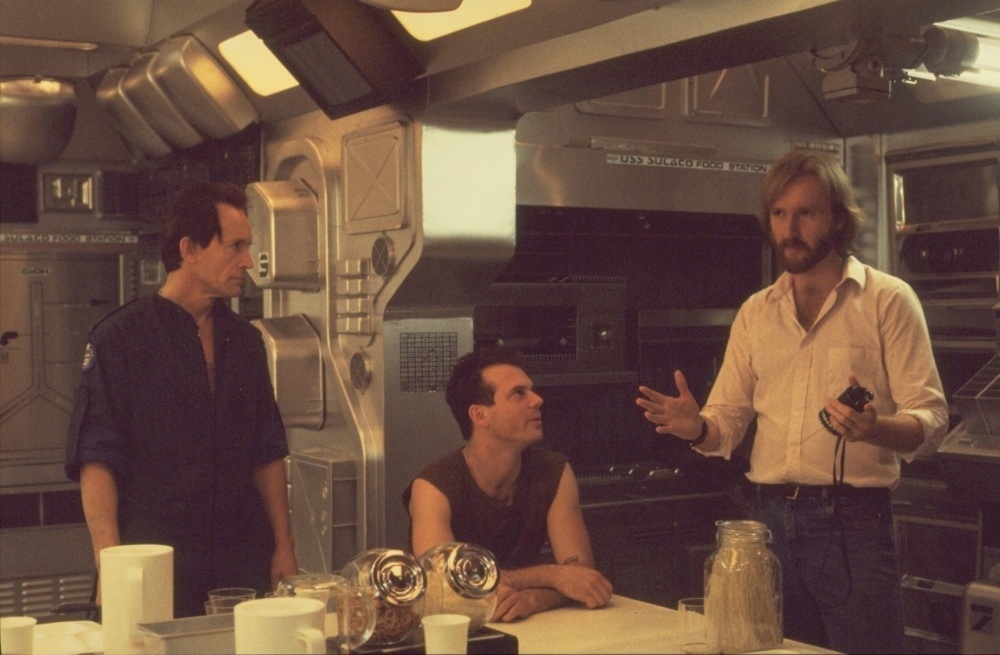

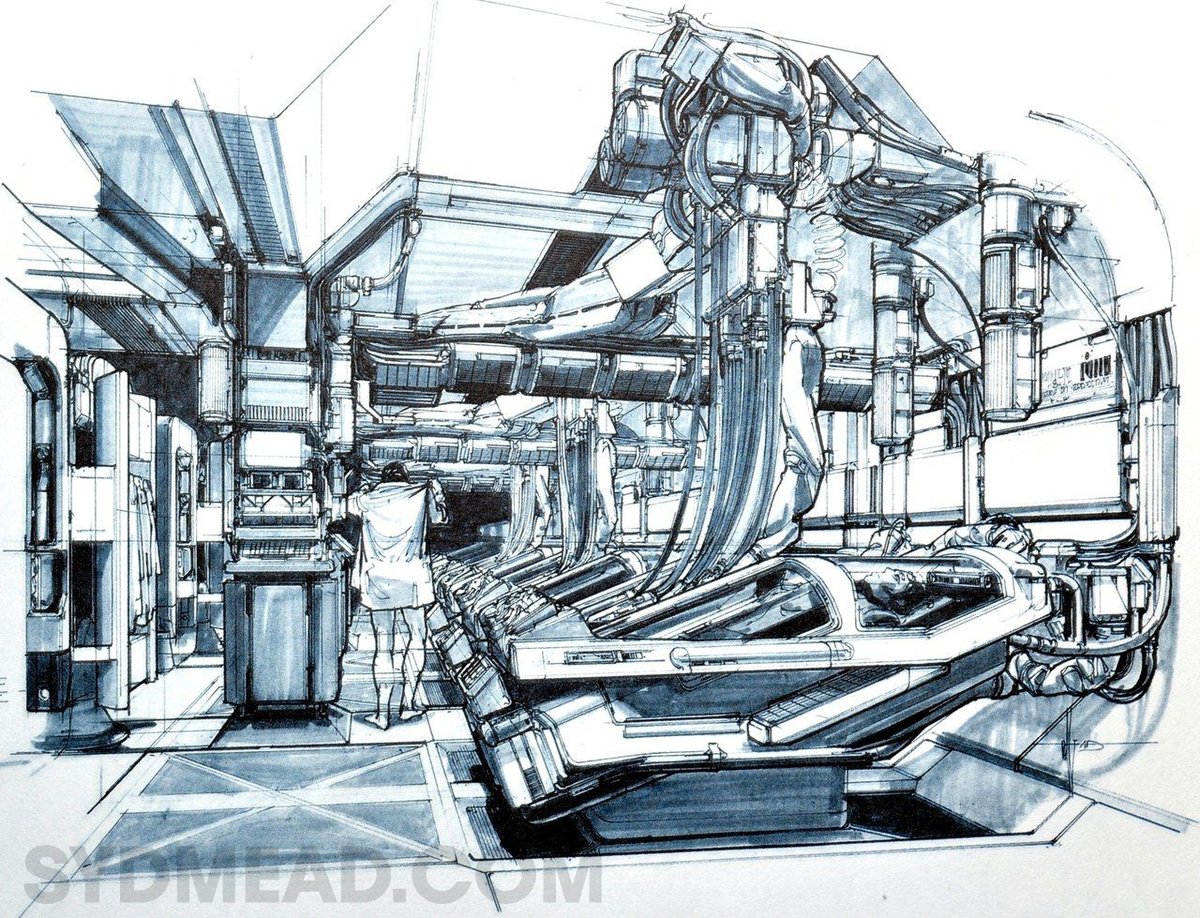

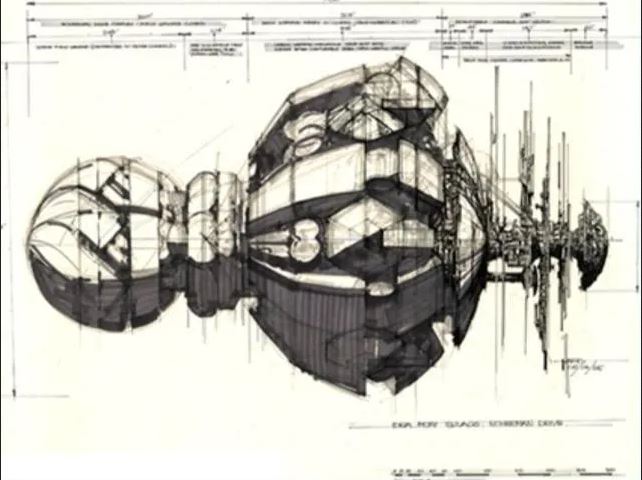

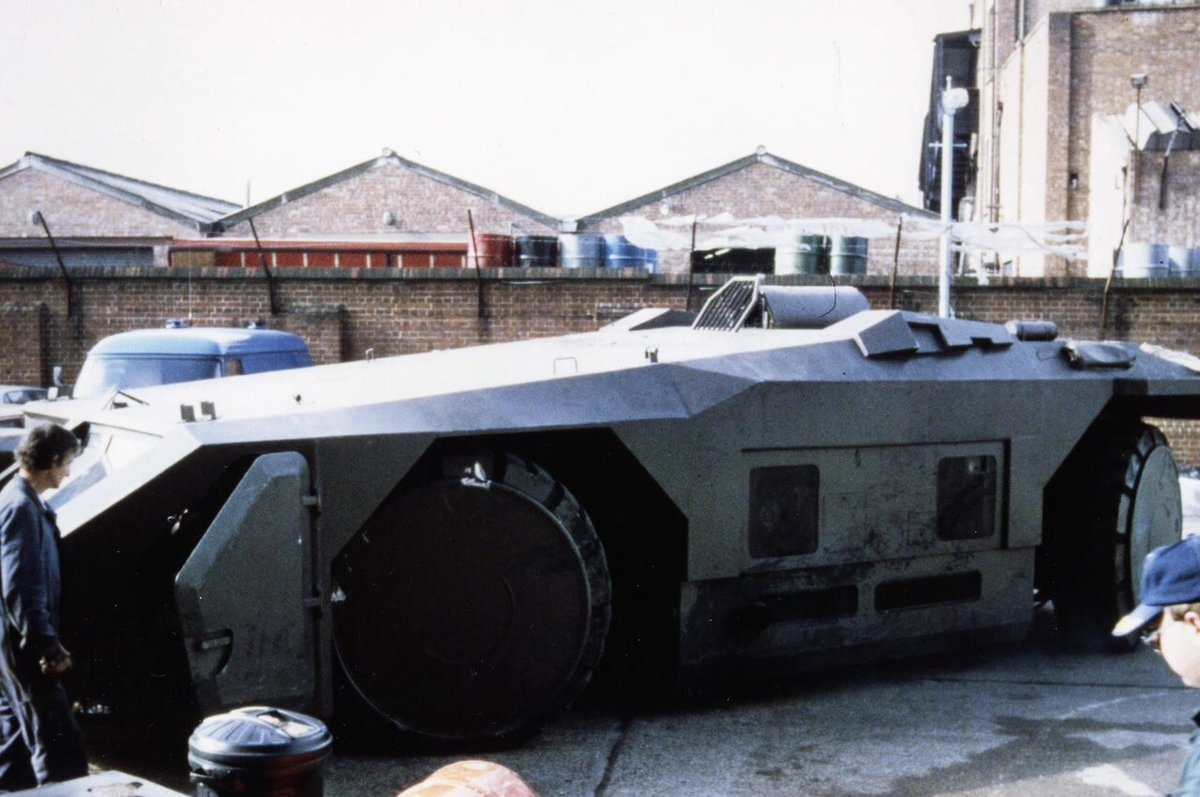

Concept artists Syd Mead and Ron Cobb were brought in to design the vehicles and sets. Together with Cameron, they created the look of the world.

17/51

17/51

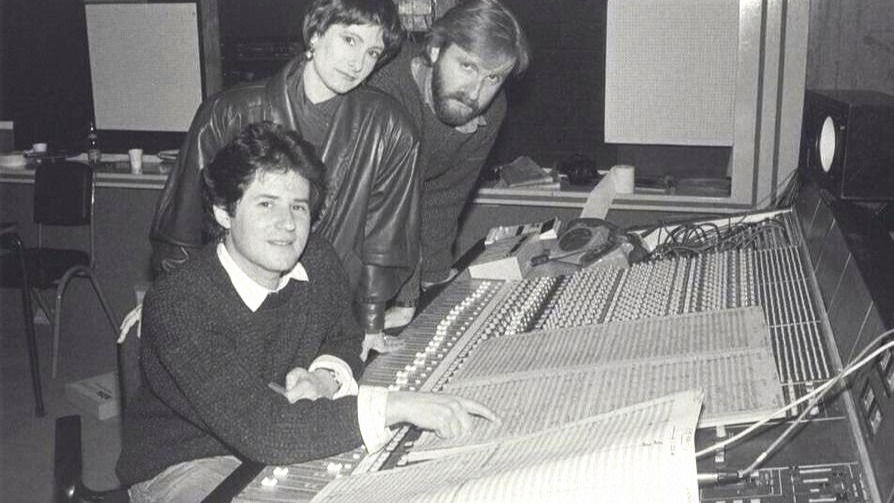

Composer James Horner was given only 6 weeks to compose all of the music, a very tight timescale by any standards. This led to some tensions and there was some conflict between Horner and Cameron through production.

18/51

18/51

In order to hit the deadlines, Horner took parts from his score for Star Trek II: The Wrath Of Khan. Cameron then re-edited some scenes after Horner had written the music, so he had to re-write the music, much to Horner’s frustration.

19/51

19/51

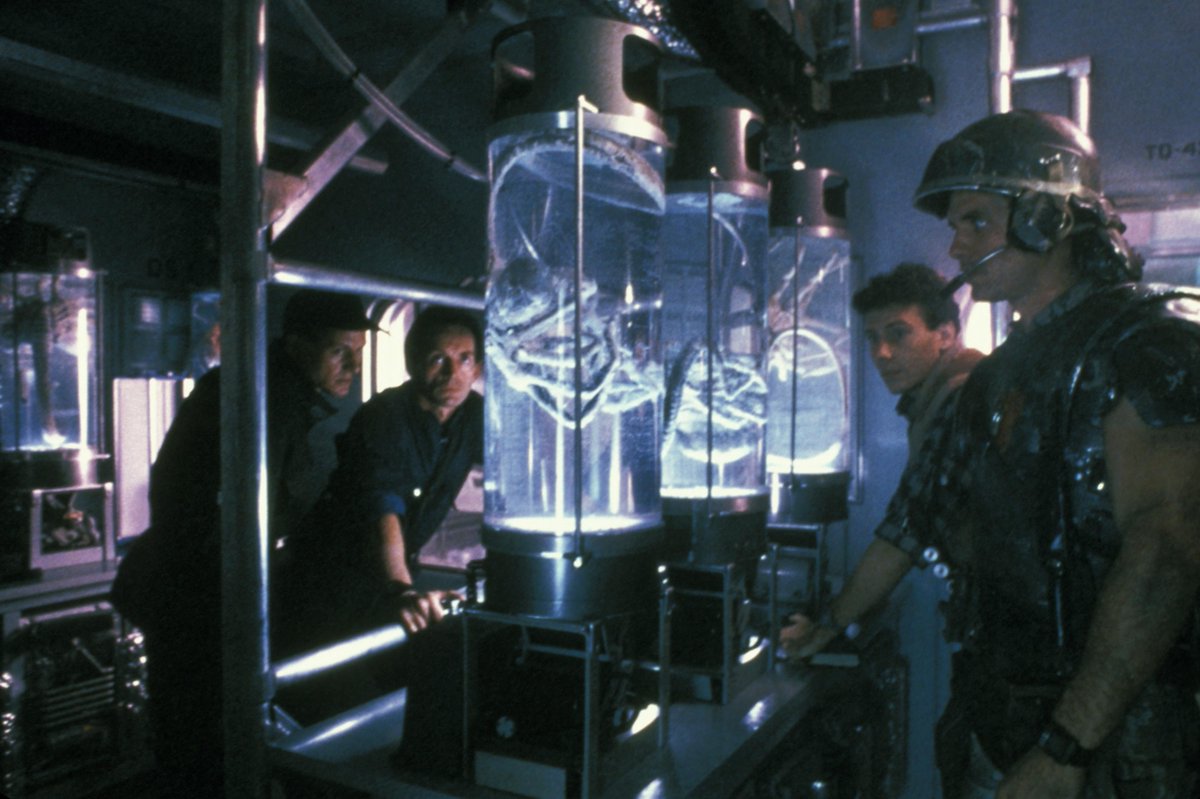

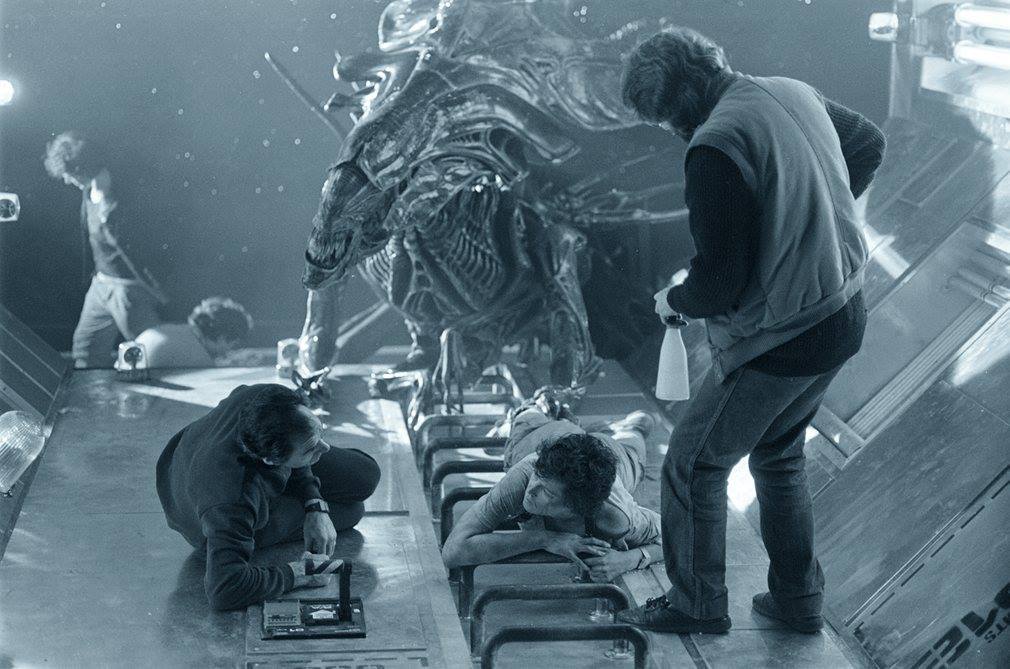

The aliens were, mostly, actors in rubber suits. Cameron only had budget for 6 so shot in a way to give a sense of many aliens, and not reveal so much that they were actors in suits. The editor was Ray Lovejoy and he was nominated for an Oscar for Best Film Editing.

20/51

20/51

Stan Winston’s team made 8ft models of aliens which were used for shots like aliens exploding or being run over. The alien model was filled with yellow dye and chemicals that, when mixed, would produce smoke. So when the alien exploded it would look like burning acid.

21/51

21/51

Most of the shots where the aliens are moving through the air ducts were filmed using a vertical shaft where the camera is at the bottom of the shaft looking up, and the actor is lowered headfirst on a cable. Then the footage was sped up.

22/51

22/51

The first DP on the film was Dick Bush. When Bush saw the shooting schedule, he apparently told Cameron the deadline wasn’t feasible. Also, Bush reportedly wouldn’t follow Cameron’s lighting instructions, leaving Cameron no choice but to fire him.

23/51

23/51

After Bush was fired, Fox recommended Adrian Biddle take over, who had worked with Ridley Scott on TV ads and was happy to work how Cameron wanted. Together, Cameron and Biddle put together some astonishing visuals.

24/51

24/51

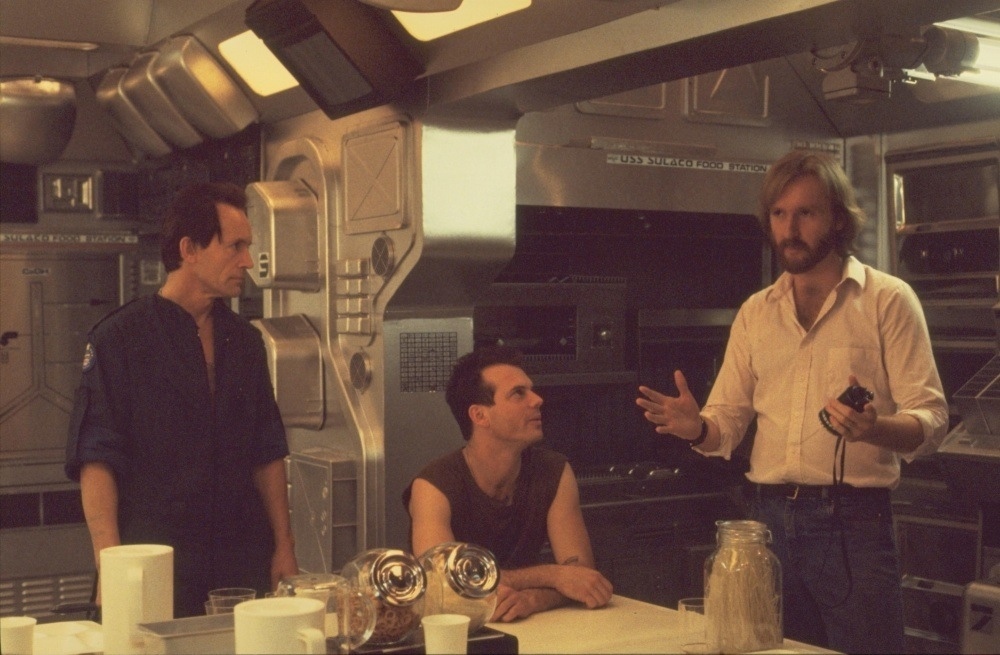

Cameron and the British crew didn’t get on. The crew – in Cameron’s words – were “slow as shit.” As well as Dick Bush, Cameron also fired Assistant Director Derek Cracknell when he refused to follow Cameron’s instructions, leading to the crew briefly downing tools.

25/51

25/51

To try and convince the crew he had the talent for the job, Cameron arranged a screening of The Terminator for the cast and crew. The cast turned up, but the crew didn’t.

26/51

26/51

The crew would stop for breaks several times a day. A lady would come in with a trolley with tea and cheese rolls. One day, Cameron was incensed that, according to some reports, he pushed the trolley over.

27/51

27/51

The crew would stop work every Friday afternoon for a draw where the winner would get about £400. Michael Biehn later backed Cameron up for being annoyed, saying “F*** the Draw!!”

28/51

28/51

On the final day of shooting, Cameron stood up in front of the entire crew to make what everybody thought was going to be an emotional farewell speech, as below (source: The Futurist, Rebecca Keegan):

29/51

29/51

Cameron has a cameo. In the opening scene, a salvage team find Ripley in hypersleep. One of the team members says “Bio readouts are in the green, looks like she’s alive!” That’s James Cameron’s voice.

30/51

30/51

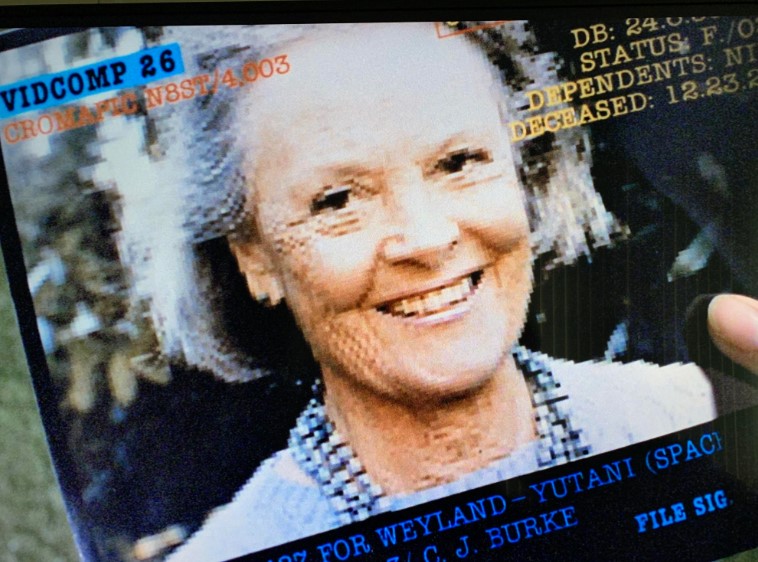

In the original script, the subplot with Ripley’s daughter, Amy, was different. Amy was alive but rejected Ripley for abandoning her by travelling into space. In the film, the photograph of Amy is actually Sigourney Weaver’s mother, Elizabeth Inglis.

31/51

31/51

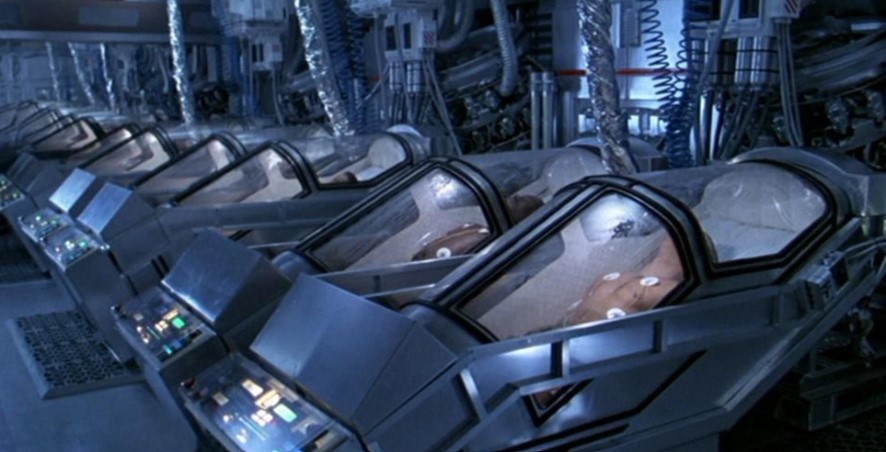

When we see the sleeping quarters on the marine ship, there are 12 capsules. Each capsule cost $4300, so the budget only allowed for 4 to be made. With some clever mirror trickery though, the crew were able to make it seem there are 12 capsules in total.

32/51

32/51

Cameron shot the scene where the marines awake from hypersleep last as he wanted there to be a lot of camaraderie, and thought this would come across more strongly if the cast had spent 14 weeks together.

33/51

33/51

The cast were trained by SAS professionals and learned drills, how to handle weapons, and work as a platoon. Al Matthews (who plays Apone) was a former Vietnam vet and helped as consultant on the film too.

34/51

34/51

The knife trick scene was not in the original script. Cameron had the idea on the set. He discussed it with everybody except Bill Paxton as he wanted to get real surprise and shock from Paxton. There is a very similar scene in John Carpenter’s Dark Star from 1974.

35/51

35/51

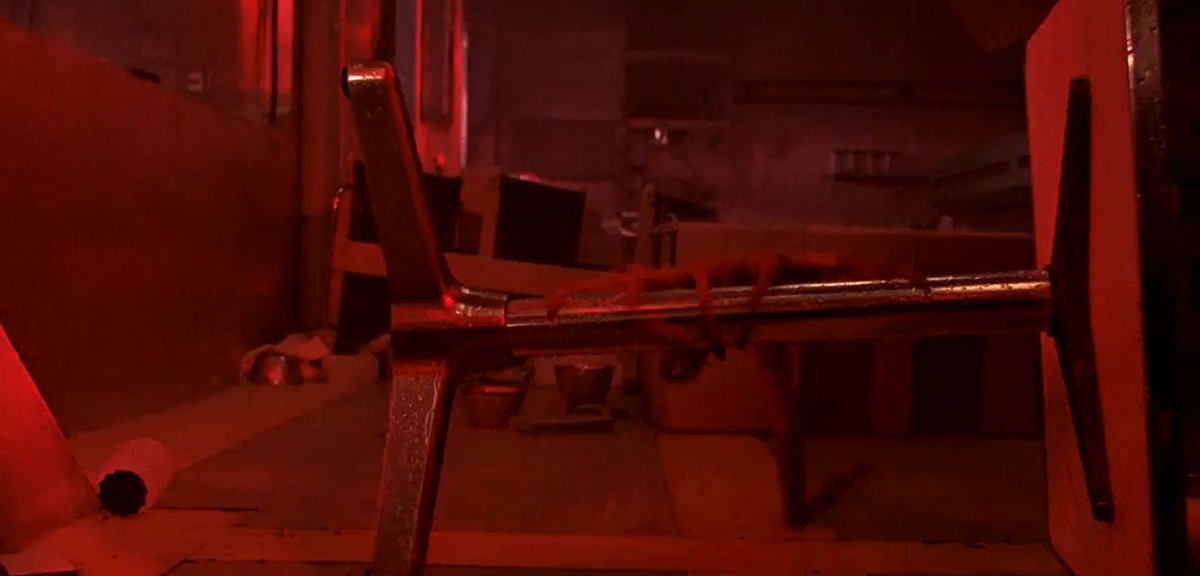

Lance Henriksen performed the knife trick at a slow speed, and the footage was sped up. You can tell because Apone, who’s next to Hudson, is laughing and his head is moving far more quickly than looks normal.

36/51

36/51

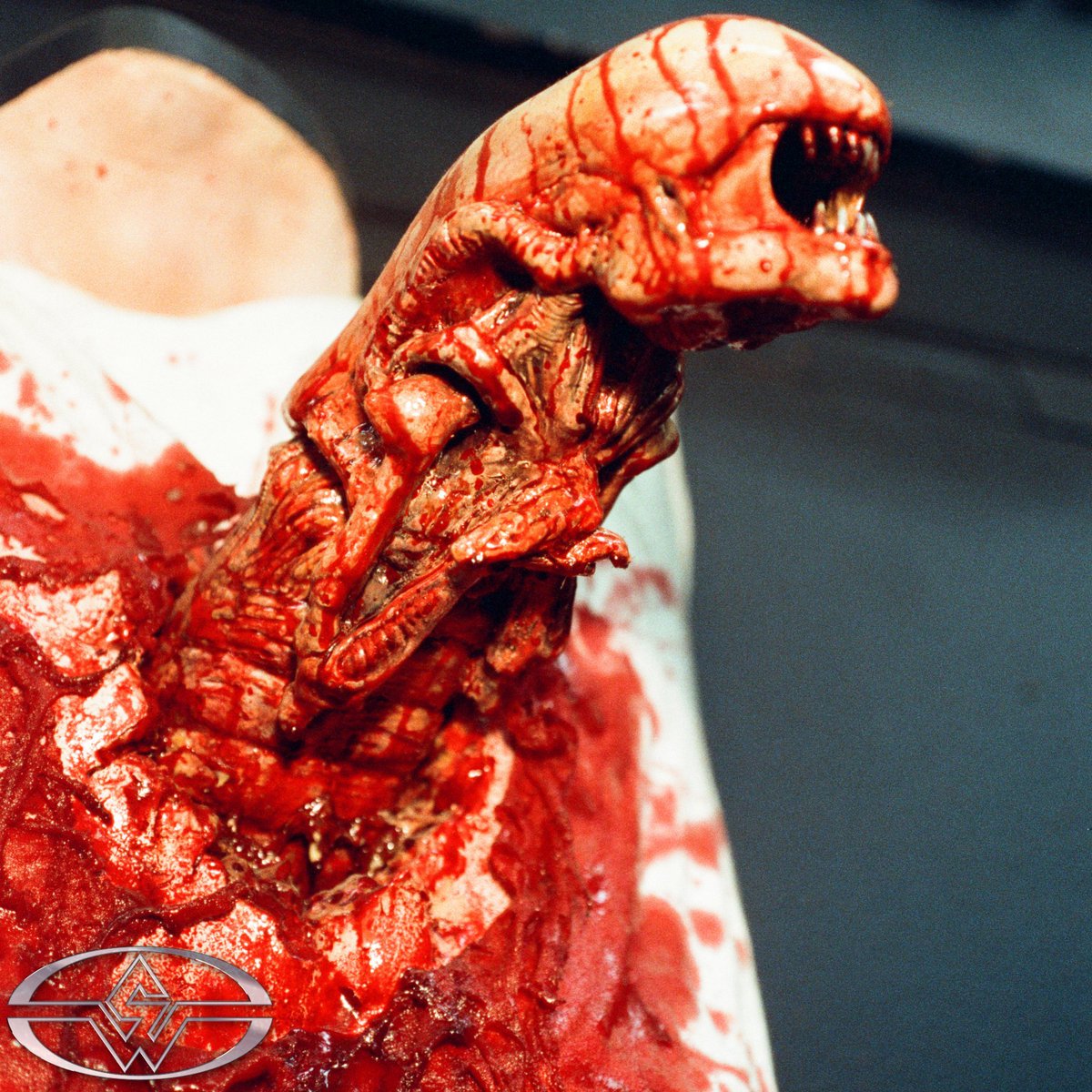

The chestburster was practical effects trickery. Actress Barbara Coles’ head was poking out of a chest model, and a puppeteer wore the alien on his arm and punched it through the chest. Coles was then replaced with a full model which was set on fire.

37/51

37/51

There were some safety problems on set, too. Filming the sequence when the marines enter the alien nest, Drake’s flamethrower sucked the air out of the set and the actors struggled to breathe. Cameron had to have the roof removed to allow ventilation.

38/51

38/51

The shot when we see the APC speeds towards camera was problematic, too. Producer Gale Anne Hurd said to Cameron to remove the camera operators just to be sure. He did, the brakes failed on the APC, and the cameras were wiped out.

39/51

39/51

Stan Winston and his effects team created functional facehuggers with moveable fingers. They had a wheel on the bottom and when it was rolled along the floor, the facehugger's legs would move to look like it was running.

40/51

40/51

To create the moment when a facehugger leaps at Ripley, 3 shots were cut together: First, they filmed the facehugger model ‘running’. They filmed pulling the model off a table, and reversed the footage. Then, they put the model on the table and pulled it towards camera.

41/51

41/51

Company man Carter Burke is presumably killed towards the end but Cameron did film a scene (later deleted) that tells us what happened to Burke. Ripley found him in the Alien Queen’s nest, having had an alien planted inside him, and left him with a grenade.

42/51

42/51

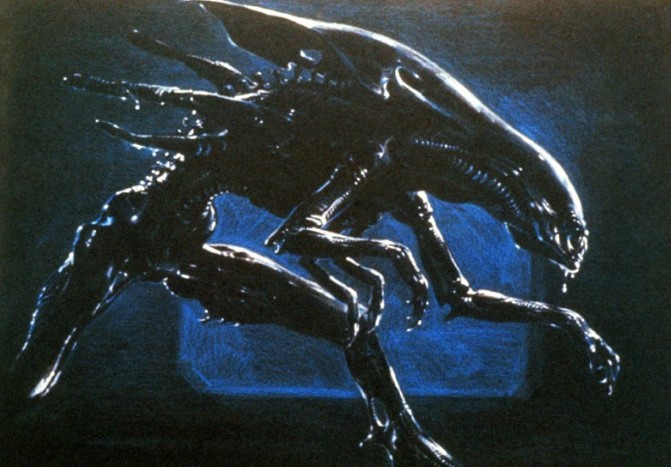

There was talk of bringing H.R. Giger (who designed the Alien) back to do design work. However, Cameron decided against it. There was only one new major design to be done, the Alien Queen, and Cameron designed her himself.

43/51

43/51

Cameron passed his designs for the queen over to Stan Winston, and told him what he wanted to achieve. Winston said: “I thought, ‘This man is out of his mind.’ Nothing like that had been done before.” They built a basic mechanism as proof of concept.

44/51

44/51

The animatronic was 14ft and had 16 operators. A combo of puppetry, cranes and hydraulic controls meant they could move her body, legs, neck, head, face, lips, jaw, and tongue all at once. Winston called the Alien Queen “the most complex construction I’ve ever created”

45/51

45/51

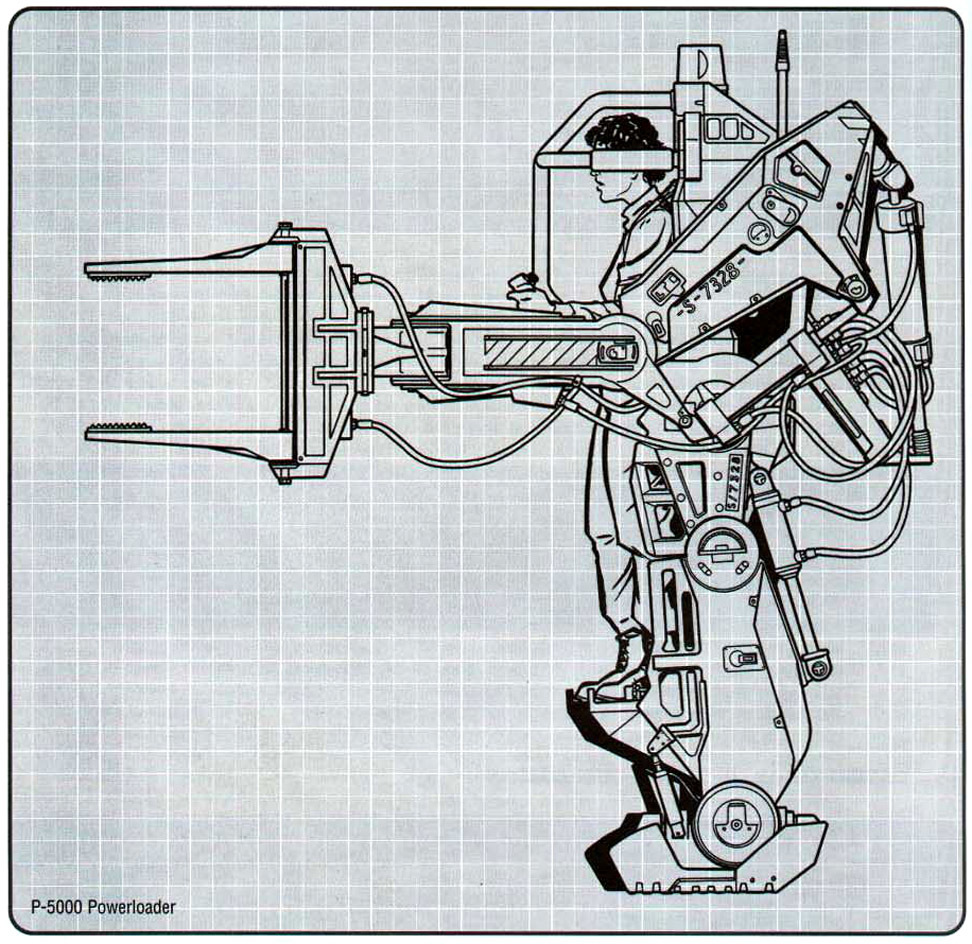

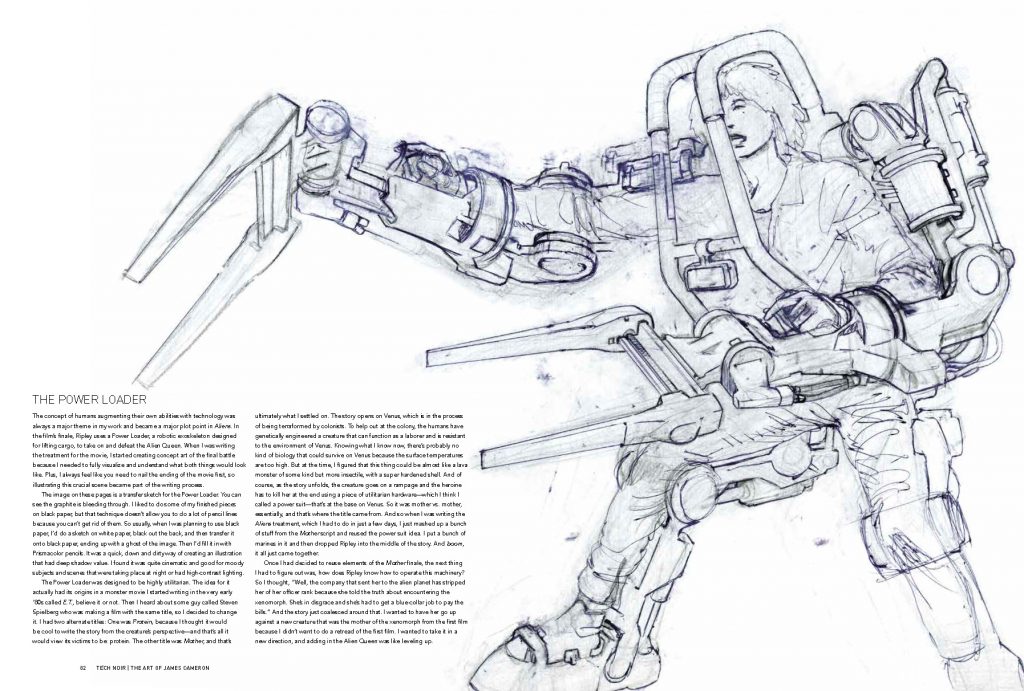

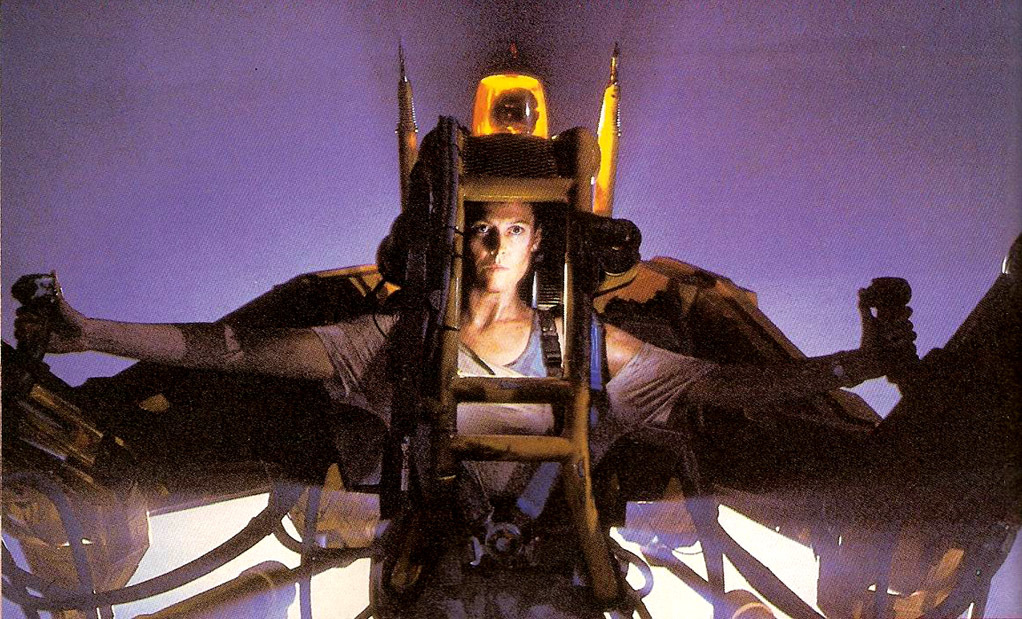

The power loader was also designed by Cameron and took 3 months to build. To move it, a crane took the weight and a stuntman inside the loader, behind Sigourney Weaver, controlled it. Weaver reacted to his movements, making it appear Ripley is moving the machine.

46/51

46/51

To create the Queen ripping Burke in two, there was a model of Henriksen built in two parts: top and bottom. This was hung in the ceiling and when the model was twisted, the two parts came apart. Wires were then used to yank the parts in different directions.

47/51

47/51

The model was filled with milk and yoghurt, and that bursts out when Bishop is ripped in half. It’s also what spurts from Henriksen’s mouth. Reportedly, the mixture wasn’t refrigerated properly and actually made Henriksen ill.

48/51

48/51

The showdown fight between Ripley and the Queen was a combination of puppetry and scale models. All seamlessly blended together with the magic of editing.

49/51

49/51

On a budget of $18m, Aliens took over $180m so was a huge success and is now acclaimed as one of the great action films. It also launched Cameron on the way to becoming one of the great blockbuster movie directors.

50/51

50/51

If you liked our making of story of ALIENS, please share the opening post 😃

https://x.com/ATRightMovies/status/1814229387203448956

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh