Aircraft are thirsty and burn lots of fuel, right?

Wrong.

The average fuel efficiency of air travel today is about 67 mpg per passenger. That makes it more fuel efficient than your drive to work. The best hit 100mpg/passenger.

How did aviation manage it?

A thread.

Wrong.

The average fuel efficiency of air travel today is about 67 mpg per passenger. That makes it more fuel efficient than your drive to work. The best hit 100mpg/passenger.

How did aviation manage it?

A thread.

It wasn't always so. The venerable 707, doyenne of the 60s jet set, was more than twice as wasteful: Its fuel consumption per hour was 50% greater than a modern 787-8, even though the 787 is 50% heavier, flies 50% further and carries a hundred more passengers.

How?

How?

Bypass ratio.

It's easier to accelerate a large volume of air gently than a small volume of air fast…

The bypass ratio is the ratio between the air mass flow through the fan and the flow through the engine core. This number has been going up & up…

It's easier to accelerate a large volume of air gently than a small volume of air fast…

The bypass ratio is the ratio between the air mass flow through the fan and the flow through the engine core. This number has been going up & up…

Lightweight materials.

Aluminium is light, but Titanium has a higher strength:weight ratio, and composite fibre reinforced plastics (CFRP) higher still. The proportion of aircraft weight given to super lightweight materials has only grown.

Aluminium is light, but Titanium has a higher strength:weight ratio, and composite fibre reinforced plastics (CFRP) higher still. The proportion of aircraft weight given to super lightweight materials has only grown.

That has run hand-in-glove with massive advances in composite manufacturing, rendering it cheaper and more accessible than ever.

https://x.com/Jordan_W_Taylor/status/1730632797734220186?t=gNE14TgKtGseBD9X7nW28A&s=19

Compression ratio.

Air must be compressed before it's combusted. A high compression ratio aids combustion and energy extraction in the turbine, so higher is better… to a point.

Air resists compression so improving this is a battle of balancing the gains against the losses.

Air must be compressed before it's combusted. A high compression ratio aids combustion and energy extraction in the turbine, so higher is better… to a point.

Air resists compression so improving this is a battle of balancing the gains against the losses.

Turbine entry temperature.

All being equal, higher turbine inlet temperatures are better for thermal efficiency. These are limited primarily by structural factors and cooling, as well as toxic Nitrogen Oxide formation.

All being equal, higher turbine inlet temperatures are better for thermal efficiency. These are limited primarily by structural factors and cooling, as well as toxic Nitrogen Oxide formation.

One early development was improving turbine blade high temperature creep resistance by moving from an equiaxed grain structure through columnar grains and finally to single crystal turbine blades.

https://x.com/Jordan_W_Taylor/status/1602708897307021316?t=dHhSSpRrydVdq1aogXkJxA&s=19

Another suite of improvements to turbine inlet temperatures came from active film cooling and the development of specialist thermal barrier coatings.

https://x.com/Jordan_W_Taylor/status/1596474257789571072?t=y8Ea7gClTnWUi6EqOk2Hag&s=19

Aerodynamics.

A thousand subtle improvements, from computer modelled optimization of fan geometry, through flexible high aspect ratio wings (aided by materials advances), low drag trim, wingtip fences for induced drag reduction.

It all adds up.

A thousand subtle improvements, from computer modelled optimization of fan geometry, through flexible high aspect ratio wings (aided by materials advances), low drag trim, wingtip fences for induced drag reduction.

It all adds up.

Here's a deeper focus on wingtip sails/ winglets, which were absent in the early jet age but almost ubiquitous now as we optimize for efficiency with tightly bound span limits, and evolving into ever more organic forms.

https://x.com/Jordan_W_Taylor/status/1652757933246103552?t=fNLPgZ0rSNioyt9DrjybOA&s=19

Automation.

The demise of the flight engineer signalled a fundamental change: Digital flight control systems and their propulsive equivalents (FADEC) can micromanage spoilers, fuel mixing, stator vane position, bleed air etc to achieve efficiencies unattainable manually.

The demise of the flight engineer signalled a fundamental change: Digital flight control systems and their propulsive equivalents (FADEC) can micromanage spoilers, fuel mixing, stator vane position, bleed air etc to achieve efficiencies unattainable manually.

The all electric aircraft.

Most notable in the 787 with it's oversized electrical generation capacity, many sub-systems previously powered by hydraulics or compressed air bleeds are going full electric for reasons of efficiency and minimising weight.

Most notable in the 787 with it's oversized electrical generation capacity, many sub-systems previously powered by hydraulics or compressed air bleeds are going full electric for reasons of efficiency and minimising weight.

https://x.com/Jordan_W_Taylor/status/1723269733582098684?t=be-bFPYx9KfqwTSEruPe6Q&s=19

Twin engines, extended range.

It's better structurally, aerodynamically and propulsively to have two big engines instead of four little ones. The certification of efficient twin engine designs for extended range operation over water was a major step.

It's better structurally, aerodynamically and propulsively to have two big engines instead of four little ones. The certification of efficient twin engine designs for extended range operation over water was a major step.

Geared fans.

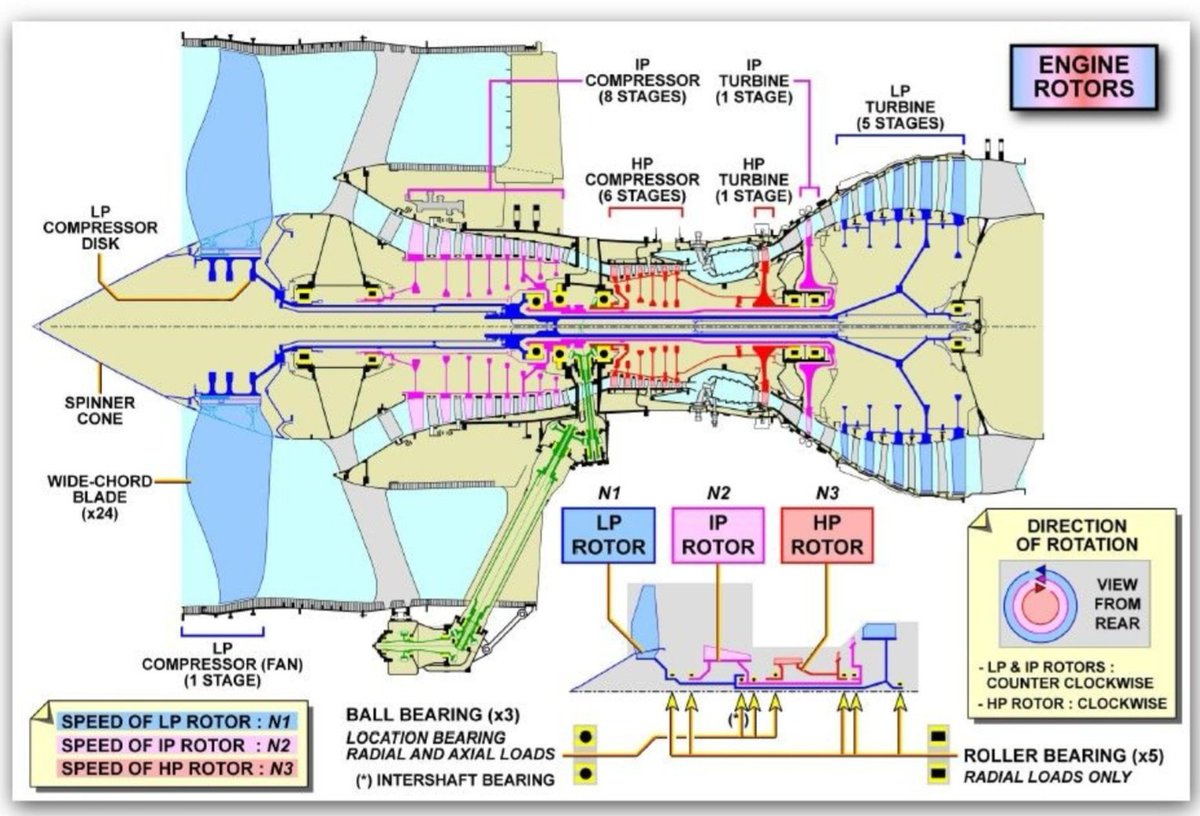

In a modern turbofan engine the fans do most of the work, turned by a shaft connecting the low pressure turbine… but the turbine’s most efficient RPM is a lot higher than that of the fan.

So what did Pratt & Whitney do? Added a gearbox!

In a modern turbofan engine the fans do most of the work, turned by a shaft connecting the low pressure turbine… but the turbine’s most efficient RPM is a lot higher than that of the fan.

So what did Pratt & Whitney do? Added a gearbox!

https://x.com/Jordan_W_Taylor/status/1710729700408959351?t=p3y4ks3_x0lypb-K8VoZBw&s=19

Blisks!

Bladed discs: Because a few big components can be much lighter than lots of assembled components.

It's tricky though.

Bladed discs: Because a few big components can be much lighter than lots of assembled components.

It's tricky though.

https://x.com/Jordan_W_Taylor/status/1654480094897872896?t=VJkeXcHrUDHSEvxlDxdyaQ&s=19

This is an incomplete list, and you can add hub airports, variable ticket pricing, seating design and a bundle of other stuff too… but it's all a tribute to the power of incremental change: Over time it moves mountains… and mountain-sized aircraft.

Let's never stop!

Let's never stop!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh