The first Olympics happened in 776 BC.

They were held for the next 1,169 years and then there was a 1,503 year break — until the start of the modern Olympics in 1896.

So, from mule racing to competitive architecture, here's a brief overview of 2,800 years of Olympic history...

They were held for the next 1,169 years and then there was a 1,503 year break — until the start of the modern Olympics in 1896.

So, from mule racing to competitive architecture, here's a brief overview of 2,800 years of Olympic history...

The origins of the Olympics are shrouded in mystery.

One myth says they were established by Heracles, in honour of his father Zeus, after completing his legendary Twelve Labours.

Still, we will never know exactly how or when they started — 776 BC is the traditional origin date.

One myth says they were established by Heracles, in honour of his father Zeus, after completing his legendary Twelve Labours.

Still, we will never know exactly how or when they started — 776 BC is the traditional origin date.

But by the 7th century BC they were firmly established.

Events included the stade (a short race), dolichos (a long race), chariot racing, and boxing, both for men and boys.

Winners — of which there was only one per event — were awarded a crown made of wild olive leaves.

Events included the stade (a short race), dolichos (a long race), chariot racing, and boxing, both for men and boys.

Winners — of which there was only one per event — were awarded a crown made of wild olive leaves.

There was also the pentathlon, contested over a single day and involving a race, javelin, discus, long jump, and wrestling.

Some unusual ancient Olympic events include mule-cart racing, trumpeting, and the hoplitodromos — a race where runners dressed as hoplite soldiers.

Some unusual ancient Olympic events include mule-cart racing, trumpeting, and the hoplitodromos — a race where runners dressed as hoplite soldiers.

Perhaps the most surprising thing about the Ancient Olympics is just how important and popular they were — because these were religious as much as sporting festivals.

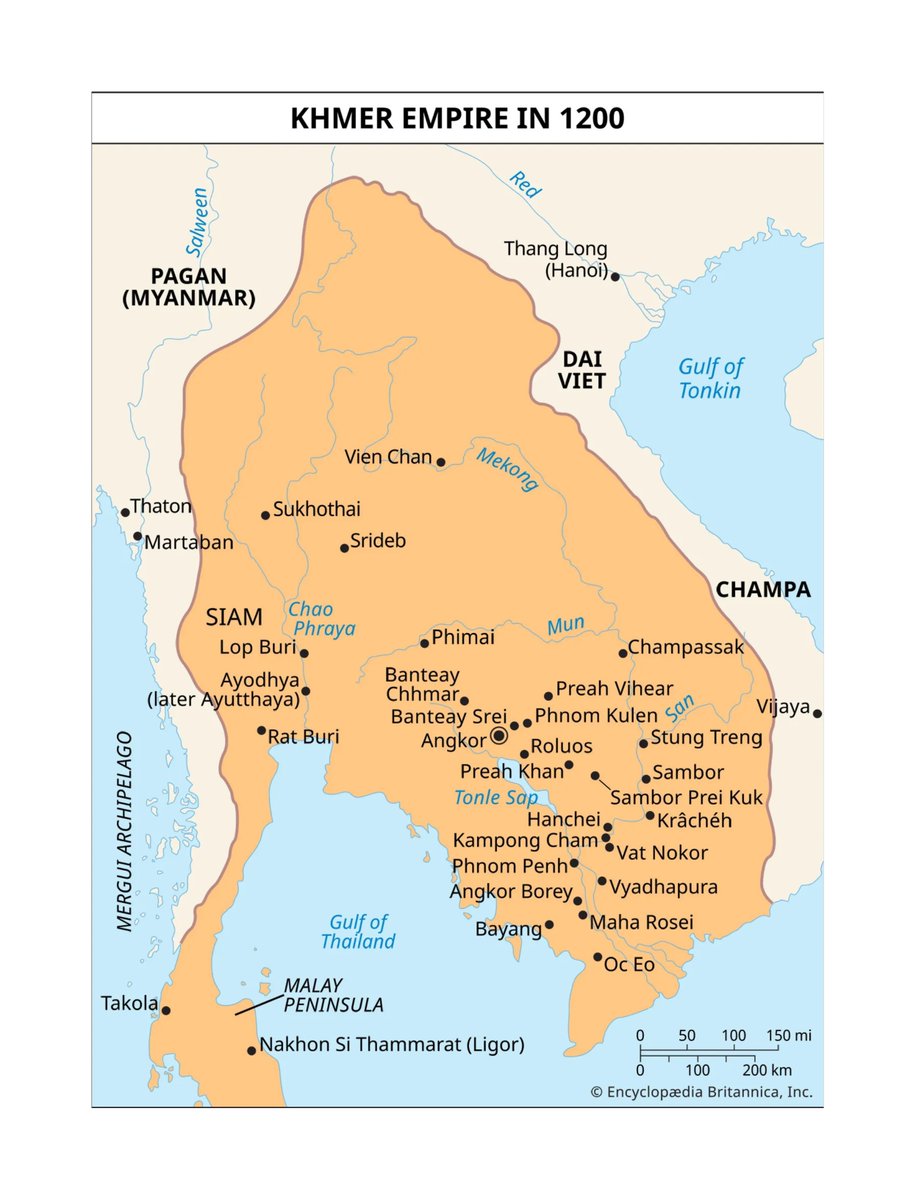

Athletes travelled from all around the Greek world, sometimes from hundreds of miles away, to take part.

Athletes travelled from all around the Greek world, sometimes from hundreds of miles away, to take part.

Ancient Greek scholars even organised history based on "Olympiads", the four year intervals between Olympic Games.

They were also important politically — truces were agreed so athletes from warring states could take part, and kings like Philip II and Dionysius even competed.

They were also important politically — truces were agreed so athletes from warring states could take part, and kings like Philip II and Dionysius even competed.

But the Olympics weren't unique — there were four Panhellenic Games, "Panhellenic" meaning all Greeks were invited.

Each took place in a specific location: alongside the Olympics there were also the Isthmian, Nemean, and Pythian Games (in Delphi).

Only ruined stadiums remain.

Each took place in a specific location: alongside the Olympics there were also the Isthmian, Nemean, and Pythian Games (in Delphi).

Only ruined stadiums remain.

The Olympics were held at Olympia, hence their name, which was the site of the most important temple dedicated to Zeus.

The Statue of Zeus, created by the famous sculptor Phidias and one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, once stood there — but has since been destroyed.

The Statue of Zeus, created by the famous sculptor Phidias and one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, once stood there — but has since been destroyed.

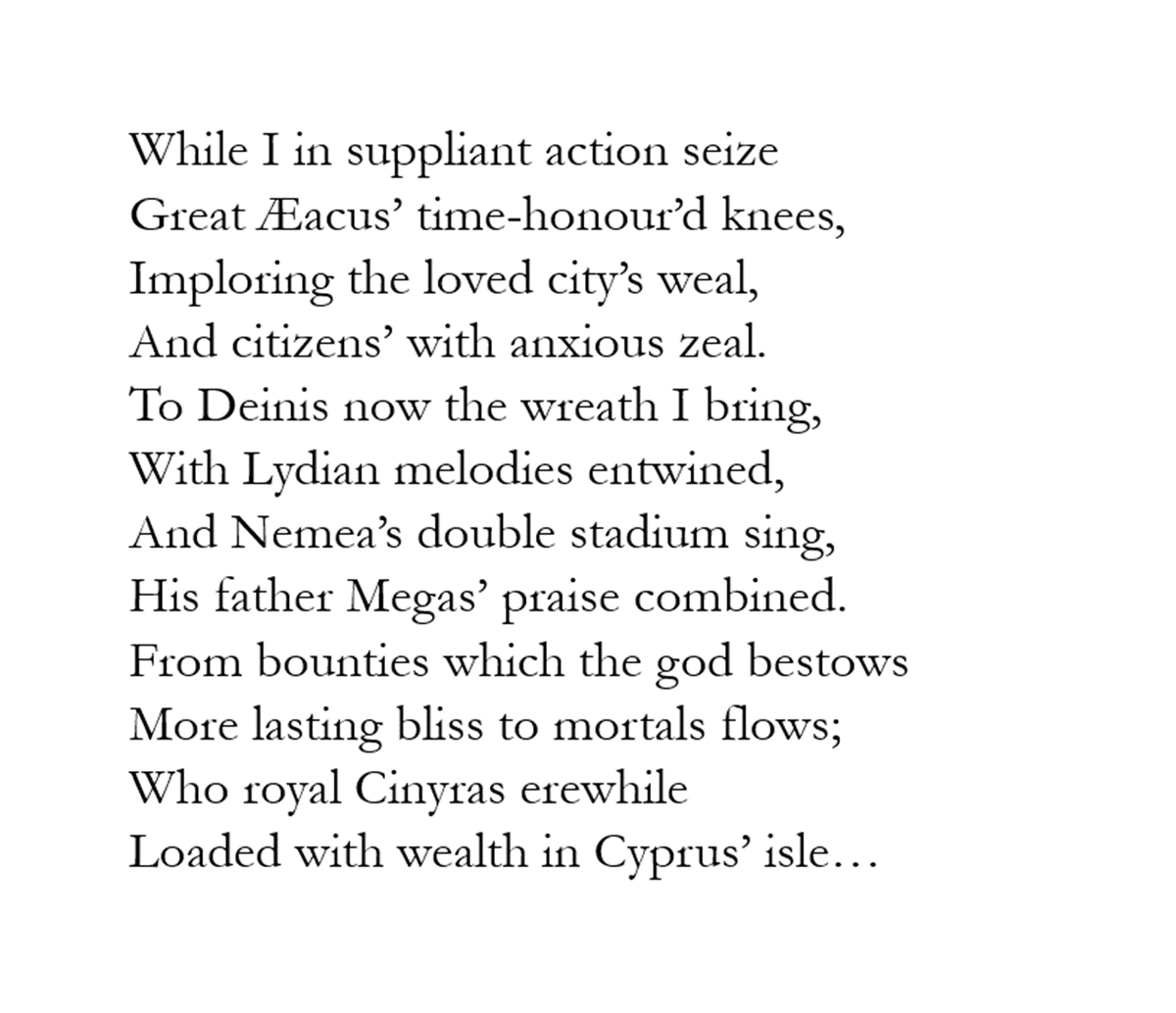

The Olympics were the most prestigious, but we know the names of victorious athletes from many of the Panhellenic Games.

Partly because of poems written in their honour, like this one by Pindar celebrating Deinis, winner of the foot race at the Nemean Games in 459 BC:

Partly because of poems written in their honour, like this one by Pindar celebrating Deinis, winner of the foot race at the Nemean Games in 459 BC:

The Olympics continued to take place long into the days of Roman rule in Greece; the last was recorded as having occurred in 393 AD.

But thereafter they melted from history — as Olympia itself fell to ruin — and would not take place again for 1,500 years...

But thereafter they melted from history — as Olympia itself fell to ruin — and would not take place again for 1,500 years...

...until Greek Independence from the Ottoman Empire.

Small-scale Olympic Games were held in Greece from the 1850s to the 1880s.

They are usually known as the "Zappas Olympics", after the businessman, Evangelos Zappas, who funded them and refurbished the Panathenaic Stadium.

Small-scale Olympic Games were held in Greece from the 1850s to the 1880s.

They are usually known as the "Zappas Olympics", after the businessman, Evangelos Zappas, who funded them and refurbished the Panathenaic Stadium.

That was a crucial step; another was the creation of the annual "Wenlock Olympian Games", founded in England by William Penny Brookes in 1850.

In 1890 a French aristocrat and educational reformer called Baron de Coubertin attended these games — and was inspired.

In 1890 a French aristocrat and educational reformer called Baron de Coubertin attended these games — and was inspired.

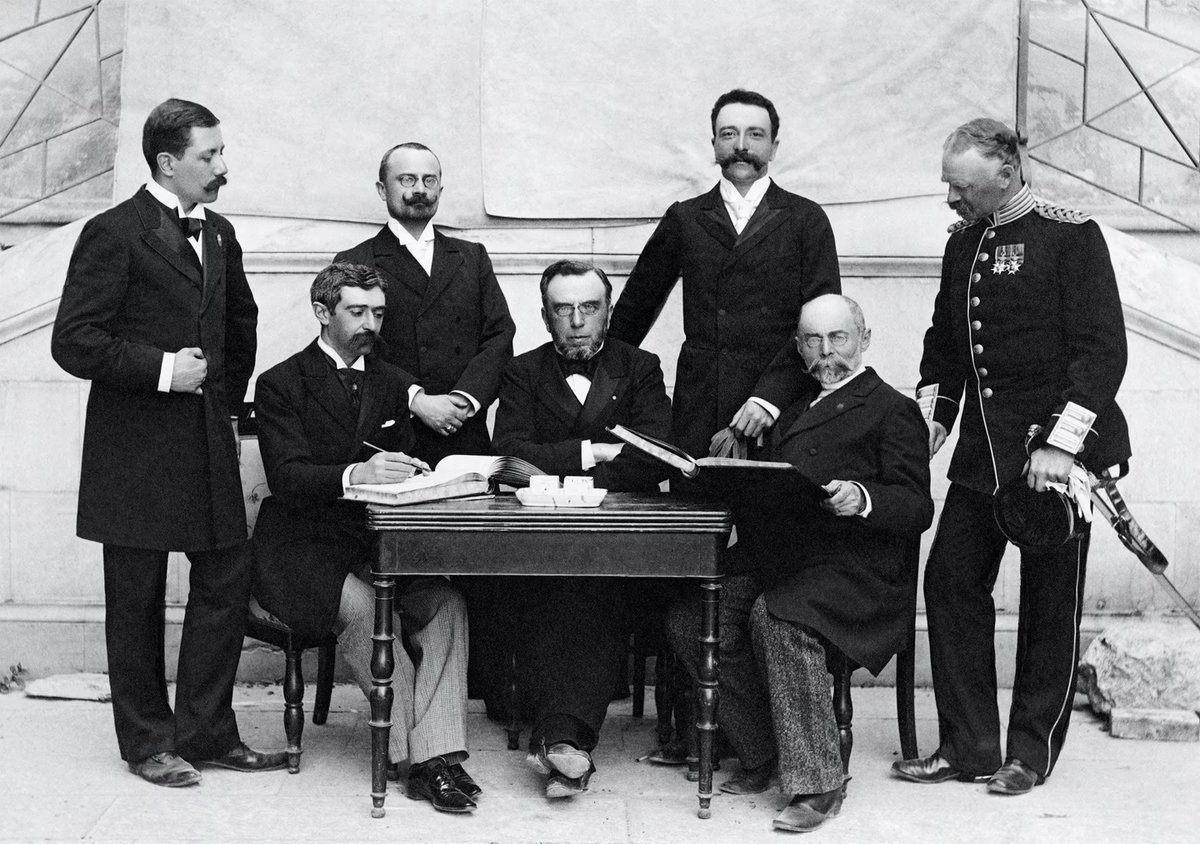

Baron de Coubertin worked with both Brookes and the Greek government, among many more people and organisations, until in 1894 the International Olympic Committee was finally founded.

The path to the modern games was clear.

The path to the modern games was clear.

But the wider context is also important.

By the 1890s the world was becoming increasingly globalised and interconnected, made possible by technologies like the telegraph and telephone.

It was also increasingly industrial and consumerist — modern society was emerging.

By the 1890s the world was becoming increasingly globalised and interconnected, made possible by technologies like the telegraph and telephone.

It was also increasingly industrial and consumerist — modern society was emerging.

See, sports as we think of them today — organised, international, commercialised entertainment — only started to appear in the late 19th century.

Sports had been popular during the Middle Ages, but in a totally different way; a new type of sporting infrastructure was needed.

Sports had been popular during the Middle Ages, but in a totally different way; a new type of sporting infrastructure was needed.

But, to cut a long story short and to elide countless important names and moments, the first modern Olympics organised by the IOC was held in Athens (which isn't near Olympia itself) in 1896.

A humble beginning — 241 athletes compared to 11,000 now — but a beginning nonetheless.

A humble beginning — 241 athletes compared to 11,000 now — but a beginning nonetheless.

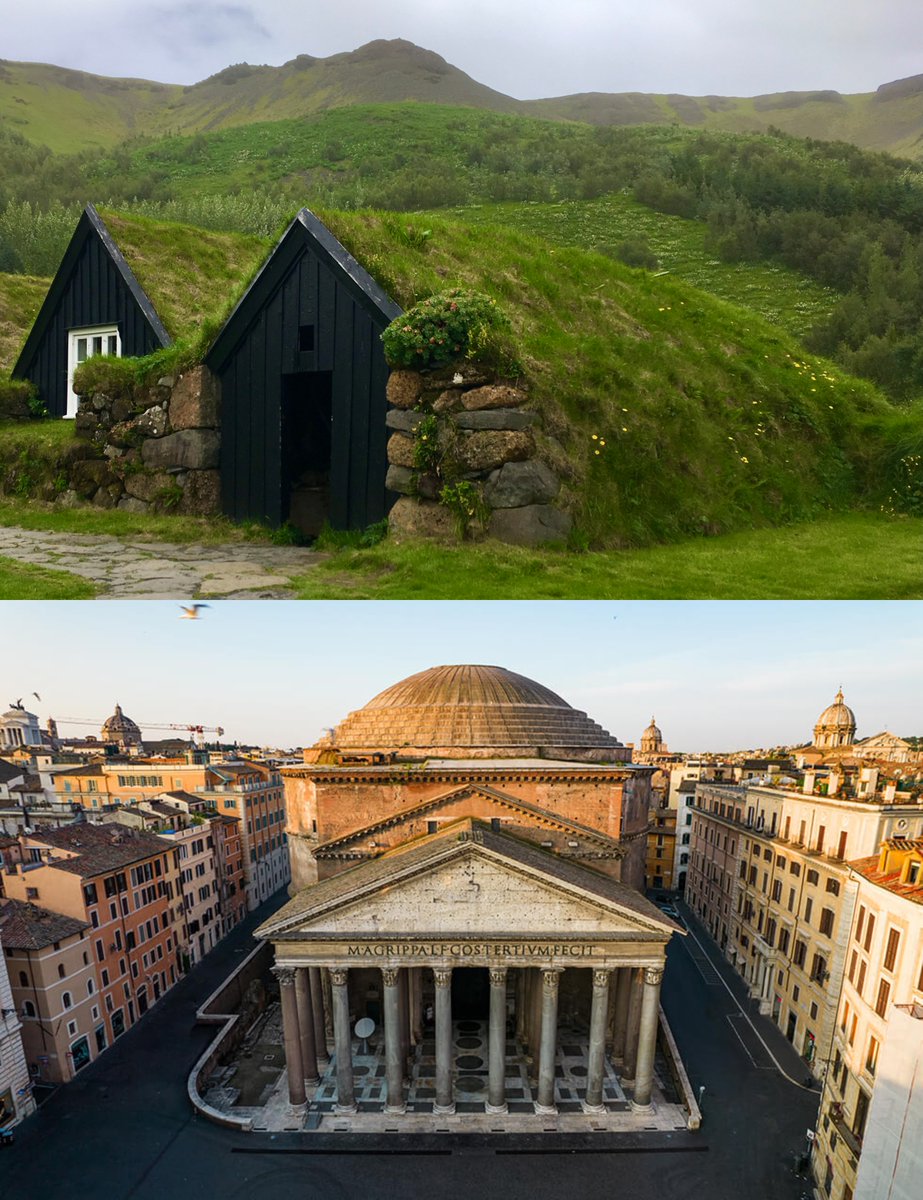

The return of the Olympics marked the final stage of a process that started with the Renaissance in the 15th century — the revival of classical culture.

Greco-Roman art, architecture, philosophy, literature, and politics had made their comebacks — now it was time for sport.

Greco-Roman art, architecture, philosophy, literature, and politics had made their comebacks — now it was time for sport.

Still, there are some major differences between the ancient and modern Olympics.

Not least that the Ancient Olympics were fundamentally, wholly, and very consciously religious.

Sacrifices were made to the gods and victors were considered to be divinely blessed.

Not least that the Ancient Olympics were fundamentally, wholly, and very consciously religious.

Sacrifices were made to the gods and victors were considered to be divinely blessed.

This much is obvious in ancient statues of victorious athletes; they are inevitably portrayed with extreme idealism and godlike serenity.

The Greeks worshipped mankind — for them athletic victory represented something close to the most divine state attainable for a mortal.

The Greeks worshipped mankind — for them athletic victory represented something close to the most divine state attainable for a mortal.

That being said, many people argue that sport fulfils a somewhat religious role in 21st century society.

How it brings people together, overcomes differences (or creates them...), conjures a sense of belonging and purpose, provides structure, and even seems to encourage worship.

How it brings people together, overcomes differences (or creates them...), conjures a sense of belonging and purpose, provides structure, and even seems to encourage worship.

Either way, the first modern Olympics were rather different to how they are now.

Partly because they were amateur (based on 19th century ideals about sporting integrity), partly because of their scale and peculiar organisation, and partly because they weren't all that popular.

Partly because they were amateur (based on 19th century ideals about sporting integrity), partly because of their scale and peculiar organisation, and partly because they weren't all that popular.

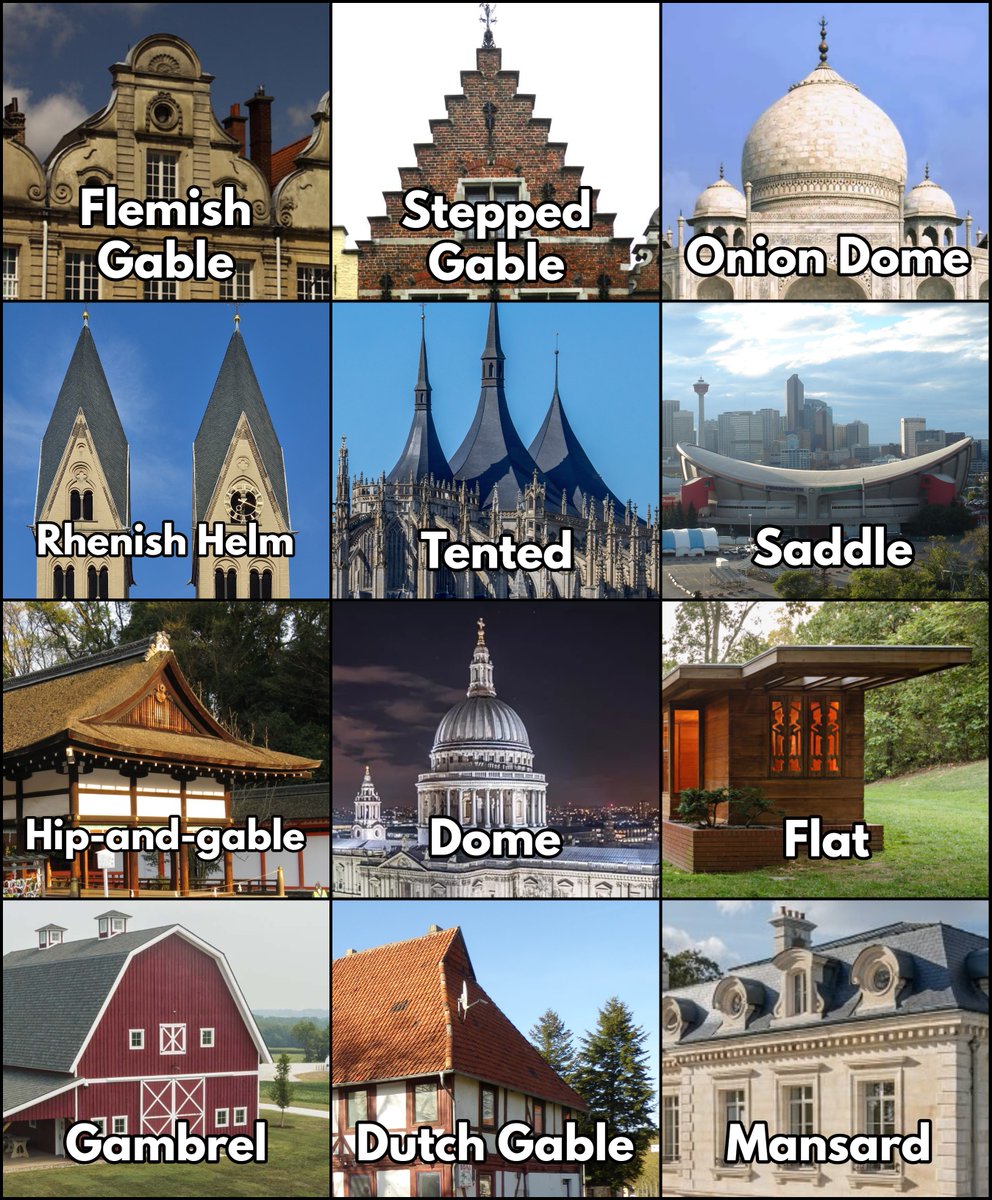

And some of the events from the early Olympics are quite surprising, such as the competitions for architecture, painting, music, and literature.

A man called Jan Wils won the 1928 Gold Medal for Architecture... for his design of the stadium at that year's Games in Amsterdam.

A man called Jan Wils won the 1928 Gold Medal for Architecture... for his design of the stadium at that year's Games in Amsterdam.

Since then the Olympics have evolved greatly, of course, what with the introduction of professionalism and of additional games like the Paralympics and Winter Olympics, along with so many more changes.

They are now a global cultural, political, social, and commercial phenomenon.

They are now a global cultural, political, social, and commercial phenomenon.

In which case they aren't so different from their ancient ancestor.

Many of those original events survive, plus the way victorious athletes are revered, and the Games continue to conjure a unique sense of international occasion.

The zenith of sport... and always something more.

Many of those original events survive, plus the way victorious athletes are revered, and the Games continue to conjure a unique sense of international occasion.

The zenith of sport... and always something more.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh