The threads Philip's is replying to contains both polemical and apologetic takes on dhimmi rights in Islam and Islamic law which contain many common misconceptions. I'd therefore like to offer some clarifications concerning some of these. A thread.

https://twitter.com/DrPhilipWood/status/1823858872869904841

First and foremost, we need to make a distinction between what Islamic law requires and what individual rulers who happened to be Muslim demanded of their subjects. The former is (classical, traditional) Islam and the latter a ruler's (arbitrary) decision. As is widely known,

literary source material accuse the Umayyads of discriminating against converts, which I believe is the reason @elicalebon calls converts 2nd-class citizens in Islam. That may or may not be true, but it bears reminding that these sources also call the Umayyads out for not having

adhered to the requirements of Islamic law and for being bad Muslims for not having allowed converts to enjoy the same rights and privileges as other Muslims. In other words, it's not Islamic law discriminating against Muslims but certain rulers who happened to be Muslim and were

considered bad Muslims exactly because of this. I personally believe these narratives impose their understanding of how things 'should have worked' back then on the events and that the real reason the Umayyads turned away (some) converts was because these were social climbers for

whom the Umayyads had no use--but that's for another day. Another common misconception is that the jizya was assessed at an unbearable rate, but the fact is that Islamic law has a fixed rate for the jizya whilst taxes payable by Muslims are assessed in relative terms, and thus

well-off Muslims would end up paying more than others under Islamic law (while poorest Muslims would pay less than poorest non-Muslims). Most legal manuals also emphasise that the jizya ought to be assessed at a fair and bearable rate. But this, again, is legal theory, and in

practice we actually have Christian sources from the early Abbasid period (such as the Chronicle of Zuqnin) not only bemoaning heavy taxation of Christians, but also commiserating with *Muslim* tax payers for the unbearable rates at which they (yes, the Muslims!) were taxed.

Actual data that would enable a comparison of the tax rates for Muslims and non-Muslims, however, is regrettably missing, and thus at the moment there is little we can say about the issue (I am working on an unpublished papyrus fragment that gives the rates for both, however).

Yet another widespread idea is that Miaphysite Christians and Jews welcomed Muslims as liberators. This, as Philip notes, represents a rewriting of history at the behest of Miaphysite leaders in later centuries in the interest of striking a mutually beneficial modus vivendi with

the ruling Muslims. However, in the case of Jews, this is indeed an undeniable reality: Jewish apocalyptic material dating to the Umayyad period all, without a single exception, speak very positively of Islam and early Muslim rulers, celebrate ʿUmar as a saviour and Muʿāwiya and

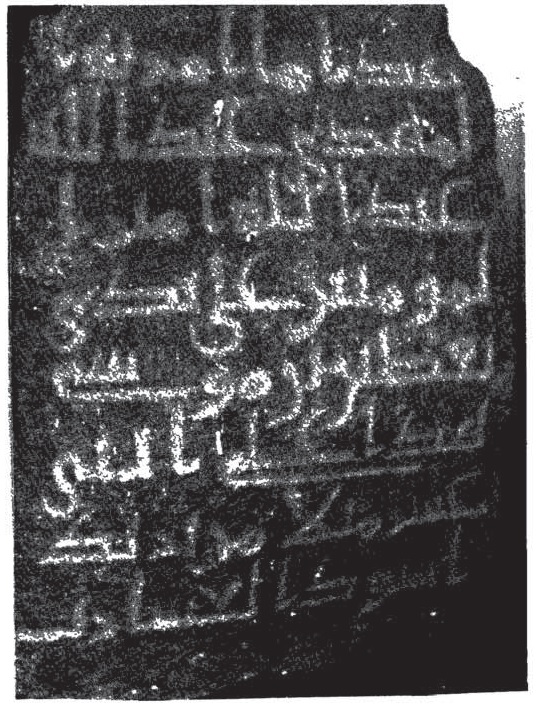

ʿAbd al-Malik as God-inspired sovereigns. It is only beginning with the Abbasid revolution that Jewish attitudes towards Islam take a turn for the negative, and there even is some evidence for limited Judaeo-Muslim convivencia in this period:

academia.edu/264837

academia.edu/264837

But a final point that I would like to make in respect of @AkyolinEnglish's thoughtful observations is that subjecting premodern phenomenon and practice to modern moral standards is always hazardous and, I would say, even counter-productive. Comparing the dhimma or Ottoman millet

systems to modern liberal democracy would only make sense in a modern context, for instance when comparing the Islamic Republic to European secular states. And while comparing the tolerance of Islamic law in comparison to the supposed intolerance of mediaeval Christiandom can

help one score an apologetic point (and I'm not using the term in a pejorative manner, as this is sometimes needed to provide context), I believe as historians and intellectuals we can actually go beyond these at-times simplistic dichotomies. I am at the moment working on a

monograph on the fiscal regime in the Umayyad and early Abbasid periods, where I hope to map out and contextualise the development of classical Islamic fiscal law and how and why it came to differentiate between the Islamic state's subjects on the basis of their religion, but

only and only so in the Abbasid period. Stay tuned!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh