MONTY PYTHON’S LIFE OF BRIAN was released 45 years ago today. The second entry in the Monty Python film series, and regarded among the great British comedies, the story of how it was made will have you asking what have the Romans ever done for us…?

1/47

1/47

Following the success of Monty Python and the Holy Grail in 1976, another film featuring the British comedy troupe was always on the cards and, when promoting Holy Grail in Amsterdam, two of the Pythons – Eric Idle and Terry Gilliam – came up with an idea.

2/47

2/47

They wrote a sketch where Jesus’ cross was falling apart and he angrily berates the carpenters responsible. Discussing with the Python team, it was decided their next film would lampoon the New Testament in the same way Holy Grail had the legend of King Arthur.

3/47

3/47

Fleshing out the idea into Life of Brian, the story of a man born one stable down from Jesus who becomes mistaken for the Messiah, the Pythons pitched the idea to EMI Films, who had distributed Holy Grail. They were keen and greenlit the movie.

4/47

4/47

The Holy Grail had been co-directed by Gilliam and fellow Python, Terry Jones. Having just directed Jabberwocky and worked with “real actors” though, Gilliam decided to remain on production design duties, and let Jones direct the film in full.

5/47

5/47

Disaster struck when, just two days before the cast and crew were due to fly out to Tunisia to begin the shoot, EMI pulled out. They reportedly got cold feet about potential blasphemy, and Gilliam said the problem was they’d finally read the script.

6/47

6/47

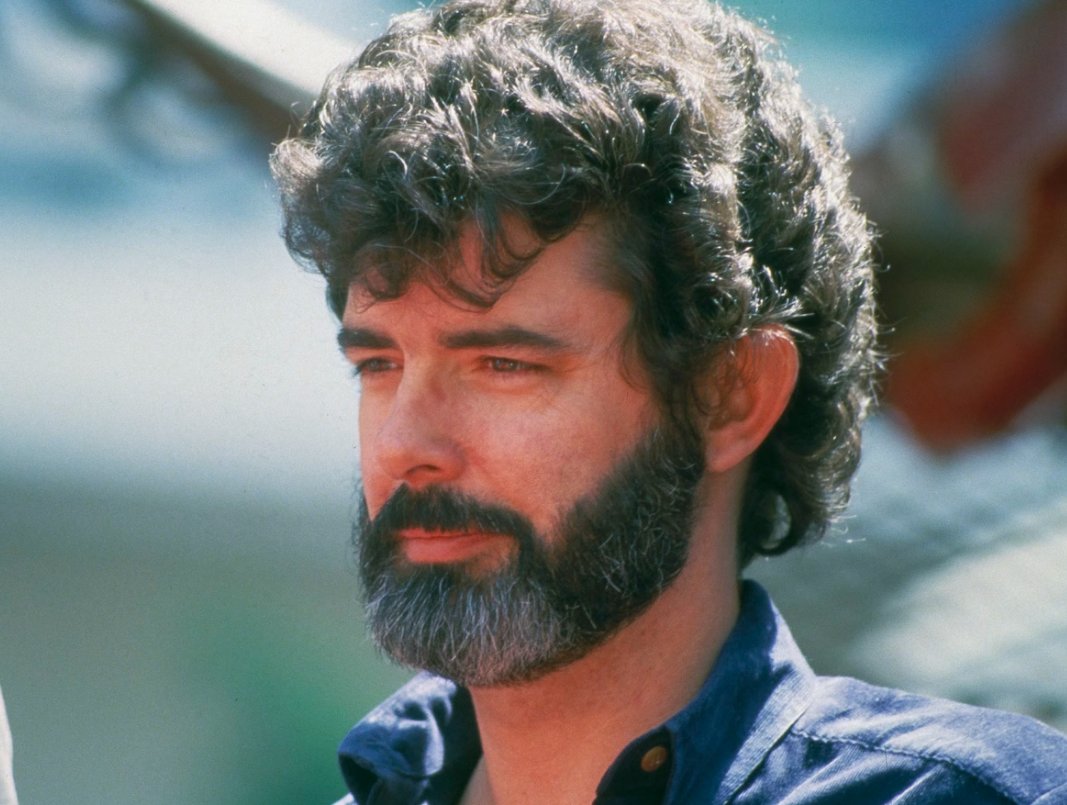

The project went on hiatus while alternative funding was found, eventually coming from an unlikely source. Former Beatle George Harrison was a friend of the Pythons and, with his business partner Denis O’Brien, agreed to stump up the $4m required.

7/47

7/47

Harrison mortgaged his home and he and O’Brien set up HandMade Films, with Harrison saying he did it as he “wanted to see the movie.” Eric Idle later joked it was “the most anybody’s ever paid for a cinema ticket in history.”

8/47

8/47

The Pythons played the bulk of the roles themselves, with 6 actors playing 40 parts. Despite John Cleese reportedly wanting to play the title character, it was agreed that he would play numerous smaller roles, and the lead would be Graham Chapman.

9/47

9/47

Chapman had previously had some issues with alcohol but dried out to play the part of Brian. He was also a qualified physician, and doubled up as the on-set doctor, holding clinics for cast and crew throughout production.

10/47

10/47

One of the 6 roles played by Cleese was that of a Roman Centurion of the Yard. He was a former Latin instructor so, during the scene when his character gives Brian a lesson in Latin, his grammar was praised as being perfect.

11/47

11/47

As for the rest of the Python’s, Michael Palin played 13 parts (including Pontius Pilate), Eric Idle played 9 characters, Terry Gilliam played 8, and Terry Jones took on 6 roles, most notably Brian’s mother, Mandy Cohen.

12/47

12/47

In casting the female lead of Judith Iscariot, Diana Quick, Maureen Lipman and Judy Loe all auditioned. Quick was reportedly offered the part but had to pull out due to other commitments. Instead, Welsh singer/actress Sue Jones-Davies was hired.

13/47

13/47

George Harrison has a cameo too. He plays Mr Papadopolus, who owns The Mount and says “’ello” to Brian. The accent is very Liverpudlian, but it was dubbed in post-production by Michael Palin.

14/47

14/47

Also, by coincidence, Irish comedy legend Spike Milligan was visiting his old Second World War battlegrounds in Tunisa at the time of filming. When the Pythons found out, they asked Milligan to play the part of a prophet.

15/47

15/47

There is a myth that the original title of the film was Jesus Christ’s Lust For Glory, when it was actually a joke made by Idle to the press. Other names were considered though, including The Gospel According to St. Brian and Brian of Nazareth.

16/47

16/47

The screenplay was written in an intense two-week Python writing session in Barbados. The first idea was that Brian would be the forgotten, 13th disciple of Jesus, but they decided to move the story away from Jesus, deciding his words weren’t worthy of derision.

17/47

17/47

When they were in the Caribbean, the Python’s had grown friendly with Keith Moon, wild man drummer of The Who. Moon was going to play a prophet in the film but tragically passed away before filming, with his role taken by Gilliam.

18/47

18/47

There are some nods to the time period the film is set in. At one point, Brian sells wolf nipple chips. This is a reference to Romulus and Remus, the founders of Rome who, according to myth, were raised from birth by a she-wolf.

19/47

19/47

A scene was filmed where we would see a group of Jewish fanatics on the rampage, with a symbol that was a combination between a swastika and the Star of David. Palin later said the scene was too much and always earmarked as one to be cut.

20/47

20/47

The Director of Photography was Peter Biziou, who had shot Bugsy Malone in 1976. Jones told Biziou that he didn’t want the film to be shot like a comedy, but rather like an epic art film, and later said “Peter did a beautiful job.”

21/47

21/47

The song that opens the film is Brian Song, performed by Sonia Jones. At the time, there were reports that it was Shirley Bassey, due to the similarity with her James Bond theme music. Quite the compliment, considering Jones was just 16-years-old at the time.

22/47

22/47

The song most synonymous with the film is Always Look On The Bright Side Of Life. It was written and performed by Eric Idle; he recorded it in his normal voice but then did a re-record in his hotel room in a cockney accent with mattresses pushed against the walls.

23/47

23/47

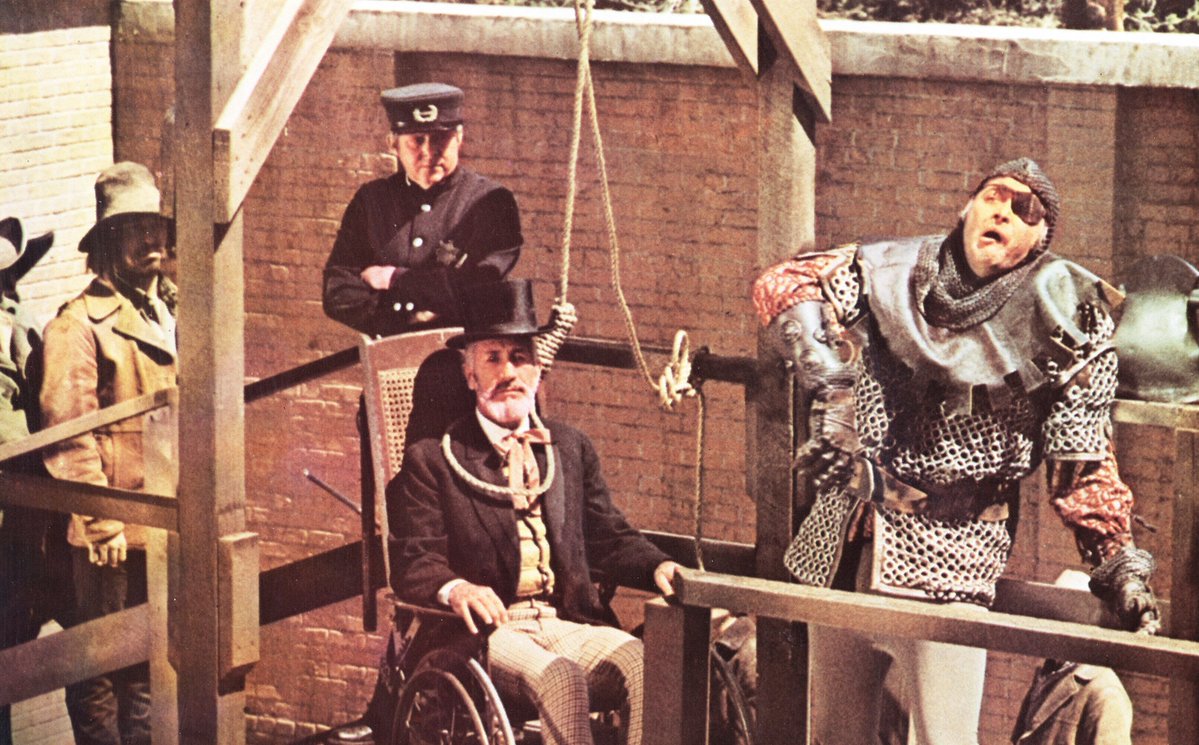

One of the main reasons the film was shot in Tunisia was that in 1977, Italian director Franco Zeffirelli had shot TV miniseries Jesus of Nazareth there. The Pythons were able to re-use many of the sets and props Zeffirelli’s production had left behind.

24/47

24/47

The costume designer was Charles Knode, who knew Python from his days at the BBC. He was granted access to many of the costumes from Jesus of Nazareth, and has a cameo in the film too; he watches Brian leave the alien ship and says "Ooo, you lucky bastard!"

25/47

25/47

Some new sets were created for the production too, and some buildings were real buildings in Montasir, Tunisia. The crew were allowed to use the buildings on condition they treat them with great respect, which they did.

26/47

26/47

Gilliam was responsible for directing the opening animation. He sourced photos of Rome and turned them upside down, mixed with “lots of laundry.” Idle later said “Terry gets a lot of angst into his animations.”

27/47

27/47

The shots in the opening act of the crowds walking towards the Sermon on the Mount came about accidentally. Mid-shoot, a lot of the female extras had left as they had to prepare food for their families. The sweeping shots are them returning to the location.

28/47

28/47

Filming the graffiti scene, fake walls were built in front of the real, sacred ones. A smudge was left on one wall though, and Jones had some crew members come back through the night and paint over the smudge. He said “I still don’t know if anyone knows about that.”

29/47

29/47

The moment Pilate dares the soldiers to laugh wasn’t scripted. The extras were only told that, whatever Michael Palin does, they weren’t to laugh. The scene was rehearsed, and then different extras were brought in for the shoot so they didn’t know what to expect.

30/47

30/47

Filming the scene where Brian appears naked in front of a large crowd, Graham Chapman was naked for real in front of 2000 extras. He said "When I flung open the shutters, half the crowd ran away screaming. That had a profound effect on my psyche."

31/47

31/47

After the first take of this scene, Jones said he had to pull Chapman to one side and say "I think we can see that you're not Jewish." The issue was reportedly rectified in the next take with a rubber band.

32/47

32/47

Jesus does appear, and Cleese apparently wanted him to be played by former 007, George Lazenby. Cleese said "I thought the poster saying 'George Lazenby as Jesus Christ' would be something people would treasure for a millennium." Lazenby was unavailable, though.

33/47

33/47

Instead, Kenneth Colley was hired to play Jesus. Colley had a stammer in real life, but not when he acted. Observant viewers may recognise him as Admiral Piett from The Empire Strikes Back.

34/47

34/47

The jokes about Welsh accents were included specifically by Terry Jones. He knew most people outside the UK wouldn’t understand but, as a proud Welshman, Jones wanted to include something his family would appreciate.

35/47

35/47

Not just religion, the film also took shots at British politics of the time. The People’s Front of Judea and The Judean People’s Front were, according to Palin, based on "modern resistance groups, all with acronyms which they can never remember and conflicting agendas."

36/47

36/47

The moment Brian leaps off a building and lands inside a UFO was filmed in camera using a model flying saucer and miniature pyrotechnic effects. It was Gilliam’s idea, and he said “He got to the top of the tower and we had to rescue him, so I said, 'OK, spaceship.'”

37/47

37/47

At the time, Graham Chapman was living in the US, and not allowed into the UK for more than 24 hours at a time for tax reasons. The UFO scene was shot in London, so Chapman had to travel to London, get to the set, shoot his scenes, then leave again within one day.

38/47

38/47

A change had to be made to the dialogue to prevent an 18 certificate in the UK. Originally, the moment Reg calls Brian a “klutz” was different – Cleese yelled “c**t” at him. It was over-dubbed, but you can still lip-read Cleese pretty easily.

39/47

39/47

The scene where we see Brian on the cross alongside others was shot very early one morning, and it was still very cold. This is why Cleese is wearing clothes, he couldn’t stand the weather.

40/47

40/47

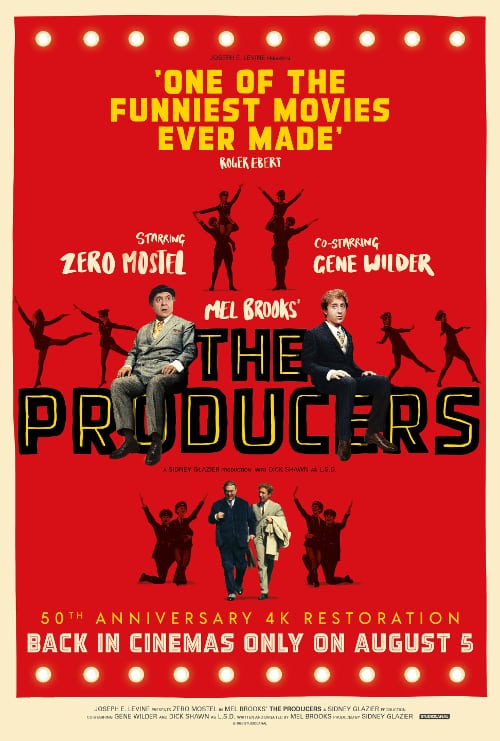

The poster has become an acclaimed piece of artwork in its own right. The design is a reference to the classic Ben-Hur poster from 1959.

41/47

41/47

The film was released in the US before the UK. This was because the US had no censorship laws around blasphemy, making it less likely the controversial content would be banned.

42/47

42/47

That didn’t stop all manner of protests from Christian groups, though. The film was banned in Norway and Ireland, and Irish movie censor Frank Hall called it "offensive to Christians and Jews as well, it made them appear a terrible load of gobshites."

43/47

43/47

There were local bans in the UK, too. Life of Brian was banned in Devon, and Bournemouth only lifted their ban in 2015. A ban in Aberystwyth, Wales was lifted in 2008 when Sue Jones-Davies was elected mayor there.

44/47

44/47

After the film released, BBC talk show Friday Night, Saturday Morning hosted a debate contested by Palin and Cleese against Catholic Bishop Mervyn Stockwood and Christian broadcaster Malcolm Muggeridge. Cleese later called them “stupid.”

45/47

45/47

Despite the controversy, Life of Brian was still a huge commercial successful. From its $4m production budget, it grossed $20.7m worldwide. And today, it regularly features highly in polls to find the greatest movie comedies.

46/47

46/47

Finally… the Head of EMI, when they pulled out had been Bernard Delfont. At the end of Always Look On The Bright Side Of Life, Eric Idle can be heard saying “Bernie, I said, they'll never make their money back.”

47/47

47/47

If you liked our making of story of MONTY PYTHON’S LIFE OF BRIAN, please share the opening post 😃

https://x.com/ATRightMovies/status/1824738205582667901

Our latest podcast is on JAWS. Full of big laughs and opinions so please give it a listen 😀

alltherightmovies.com/podcast/jaws-1…

alltherightmovies.com/podcast/jaws-1…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh