Top speed and fighter aircraft: why lower top speed can be a benefit for an air superiority fighter.🧵

This discussion requires some background information and a discussion of intended roles as they changed over time. The first place to begin is with the F-86 Sabre.

The F-86 Sabre was conceived from the start as an air superiority fighter, coming straight from the emphasis on dogfighting that had dominated fighter design since the First World War. Speed, rate of climb, roll rate, and turn performance were paramount in its design.

However, after Exercise SAGE BRUSH in 1955, Tactical Air Command realized that there was little reason to pursue air superiority in a nuclear world. The winner of a war between two major powers would be the first one to deploy nuclear weapons on the other's airfields.

In many ways this was an outgrowth of the World War Two strategic bombing doctrine of targeting enemy forces first, but with vastly increased effectiveness. The rapidity and totality of the destruction of airfields made a lasting impression on TAC, ADC, and the USN alike.

The USN's primary threat, though, came from Soviet maritime strike aircraft. First, the KS-1 Komet, then the K-10S nuclear anti-ship cruise missile. These could destroy a carrier before subsonic fighters could be scrambled to intercept the bombers.

In the case of TAC, the lessons they took were applied to the F-105, which was modified from its original design to be especially adept at low-level high-speed interdiction strikes with nuclear stores. Many USAF aircraft were also modified to be used with nuclear gravity bombs.

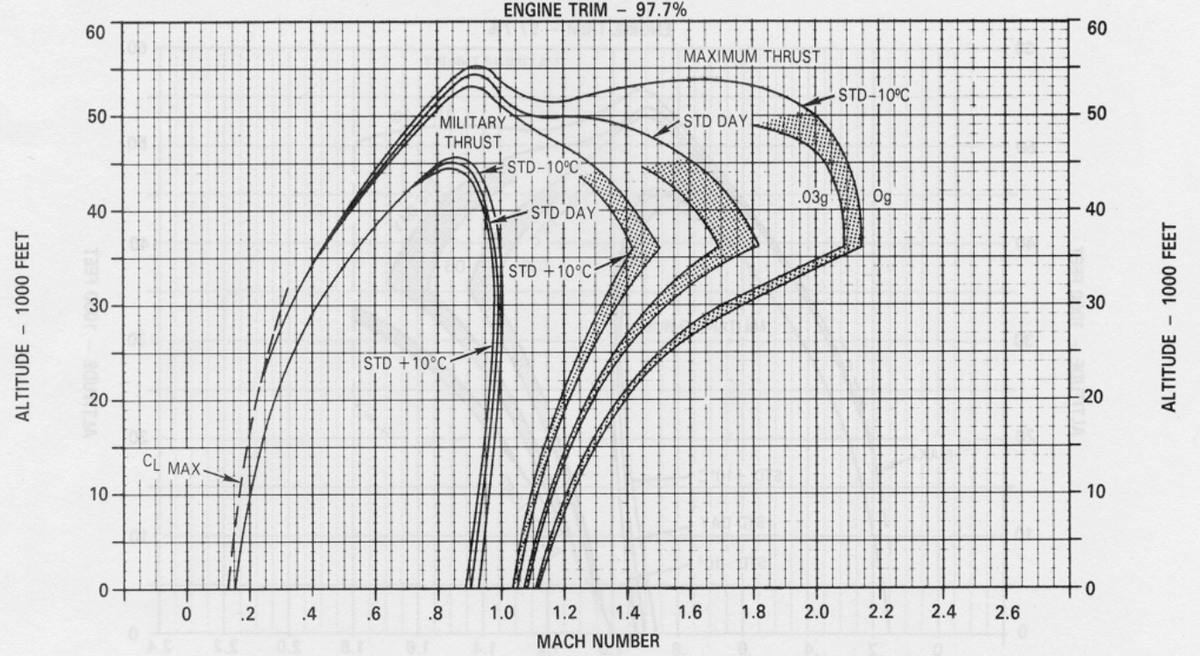

This requirement for high-speed strike almost necessitated the required top speed of at least Mach 2.0 for any future aircraft. The TFX program, which produced the F-111, showed this high-speed low-altitude requirement.

One exception to this rule was the F-104, a lightweight, easy-to-produce and maintain supersonic dogfighter based directly on the feedback from pilots who flew in the Korean War. Pilots wanted high speed, high altitude performance, maneuverability, and simplicity.

The F-104 delivered exactly what these fighter pilots wanted. Until the F-15, it was probably the best maneuvering fighter above supersonic speeds and above 30,000 feet. Even the F-106 couldn't catch it in a turn or straight line at those speeds and altitudes.

But TAC wasn't interested. It was inferior to other programs, such as the aforementioned F-105, for the nuclear strike role (that didn't stop some poor Germans in F-104s from being told to toss-bomb an airfield with a nuke in the event of a war).

Neither was Air Defense Command, whose favorite weapon of choice was high-tech interceptors like the F-102, with its radar-aimed or guided armament of AIM-4 Falcons and Folding-Fin Aerial Rockets. Thus, the 104 went unappreciated in American service.

The USN moved to develop air-to-air missiles for bomber interception, beginning in service with Sidewinder and the beam-riding Sparrow I, but quickly moving to the radar-homing Sparrow III, which gave the F3H-2 the ability to intercept an incoming bomber from a frontal aspect.

The F-4 was the next aircraft to be armed with Raytheon's Sparrow III. This was to be the USN's all-weather(radar missile equipped) interceptor to replace the slow F3H-2. It was larger, faster, had better range, and more missiles. To improve performance, guns were not included.

Though its primary target was bombers, the F-4 was expected to engage Soviet fighters at high altitude with its missiles. This fight was expected to take place at near top speed and at extremely high altitude, using technology to their advantage.

The Vietnam War, as most of you know, was a wake-up call for this kind of thinking. Fights took place at low speed, low altitude and against fighters optimized for performance in the subsonic flight regime.

Though there were many reasons for this, it quickly became apparent that high-altitude, high-speed air-to-air combat was extremely unlikely. For most aircraft, as a turn began, they bled speed due to induced drag, and quickly fell out of the supersonic range.

As such, studies of dogfights in Korea, Vietnam, and the Middle East showed that fighters spent most of their time between Mach 0.5 and Mach 1.0, and below 30,000 feet.

Incredibly, a survey of 100,000 combat missions over Vietnam showed that absolutely no time was spent at the upper end of the flight regime of these combat aircraft!

Aside from the issues related to turn performance, the other major reason these speeds were not used in combat is due to the difficulty involved in reaching them.

With external stores, the F-4J's top-end acceleration was far less useful in combat. With one centerline tank (roughly equivalent to 4 sidewinders when supersonic, from what I can find), acceleration from Mach .8 to 1.8 took about 3.75 minutes of level flight and about 50NMI!

This was a massive cost in an air-to-air fight. Going beyond that would primarily be involved in running away from a fight that a pilot could not sustain, or in a pure interception role.

Even the F-14A, set up for an intercept mission with drop tanks, could take as much as 8 minutes and 110NMI to reach Mach 1.8!

The issue with operating at maximum power is that this burned fuel at an incredible rate. By the time 45,000 feet and Mach 1.4 was achieved, this F-14A (without drop tanks)would have burned almost half of its internal fuel!

A problem with this emphasis on speed is that it creates trade-offs. This can manifest as inferior low-speed maneuverability, increased cost, higher maintenance, higher weight, limited air-to-ground capabilities, and more.

For the F-X(F-15) and Lightweight Fighter(F-16) programs, the USAF would continue to insist on Mach 2+ capabilities. The F-15 achieved it on paper, but real-world performance was limited. Acceleration was equally long and fuel-intensive.

The F-15A was no slouch in terms of speed, but with 4 AIM-7s and 4 AIM-9s, speed was limited to about Mach 1.8 on a standard day. Higher sprint speeds could be achieved but were hardly used.

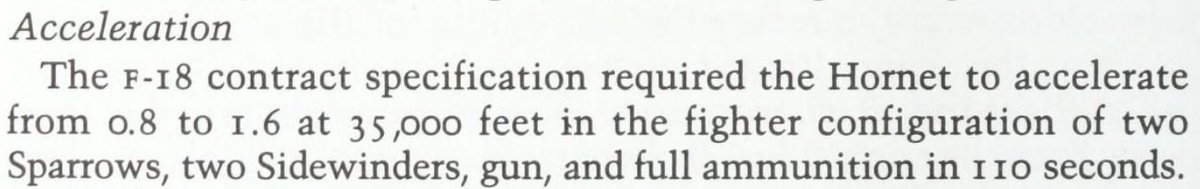

The USN, when looking at their VFAX(Navy Fighter Experimental) or NACF(Navy Air Combat Fighter), a program designed to provide an F-4 and A-7 replacement which would start with the YF-17 and culminate in the F/A-18, set no speed requirement -- only an acceleration requirement.

The YF-17 performance figures (that included a maximum speed of Mach 2.0) showed Northrop's direct connection to the speed studies that they had conducted prior. The terminology of low-speed transient, high-speed transient, & "primary area" speak volumes to their design approach.

The YF-17 Cobra was faster than the F/A-18 Hornet that would come out of NACF, but in trade, the F/A-18 had a much greater combat radius, an outstanding radar third only to the F-15's and F-14's radars, and fantastic multi-role capabilities without compromising maneuverability.

In short, the top-end speed that was never used in tactical situations was traded for performance in regions that were found far more frequently in combat and capabilities that would be far more relevant in an expected fight.

This mentality would be carried forward in future programs. The F-35 is a perfect example of the end product of this thinking. The F-35 is the most capable air superiority fighter on the market today, and yet the F-35A only maxes out at Mach 1.6.

Sometimes speed isn't everything!

As requested @Lantirn40K @actualjib @TomcatJunkie @SpockNC @Thatdude2531 @ond144 @VLO225 @taiwaneseprick @RokkerBoyy @peck_oh @steeljawscribe @KiranPfitzner @whatismoo @VLS_Appreciator @Doha104p3 @BaA43A3aHY @StrokeNdistance @EricWelch42 @coldfoot666

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh