Why did Huw Edwards avoid prison?

Is this evidence of “two-tier justice”?

Let’s take a quick look. 🧵

TLDR: This is an entirely expected sentence for offences of this type.

Is this evidence of “two-tier justice”?

Let’s take a quick look. 🧵

TLDR: This is an entirely expected sentence for offences of this type.

https://twitter.com/bbcbreaking/status/1835650426785439977

Huw Edwards pleaded guilty to “making” 41 indecent photographs of a child.

The first point to note is that “making” is misleading - the offence was possessing them on a computer, rather than creating or recording the images. The law is grossly confusing in this area.

The first point to note is that “making” is misleading - the offence was possessing them on a computer, rather than creating or recording the images. The law is grossly confusing in this area.

For an offence of possessing images of this type, the court must follow the relevant Sentencing Guideline, here: sentencingcouncil.org.uk/offences/magis…

According to reports, Edwards was in possession of 7 Category A images, 12 Category B and 22 Category C images.

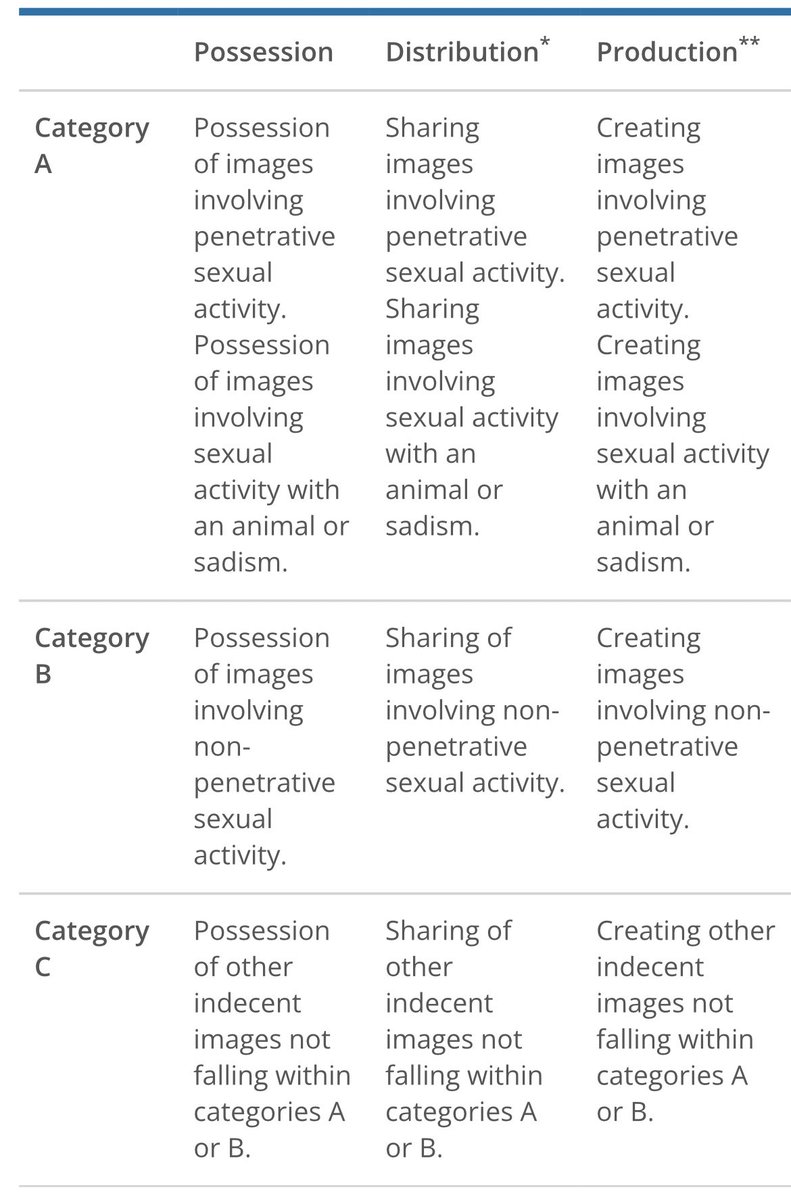

As to the categorisation of this type of material, see below:

As to the categorisation of this type of material, see below:

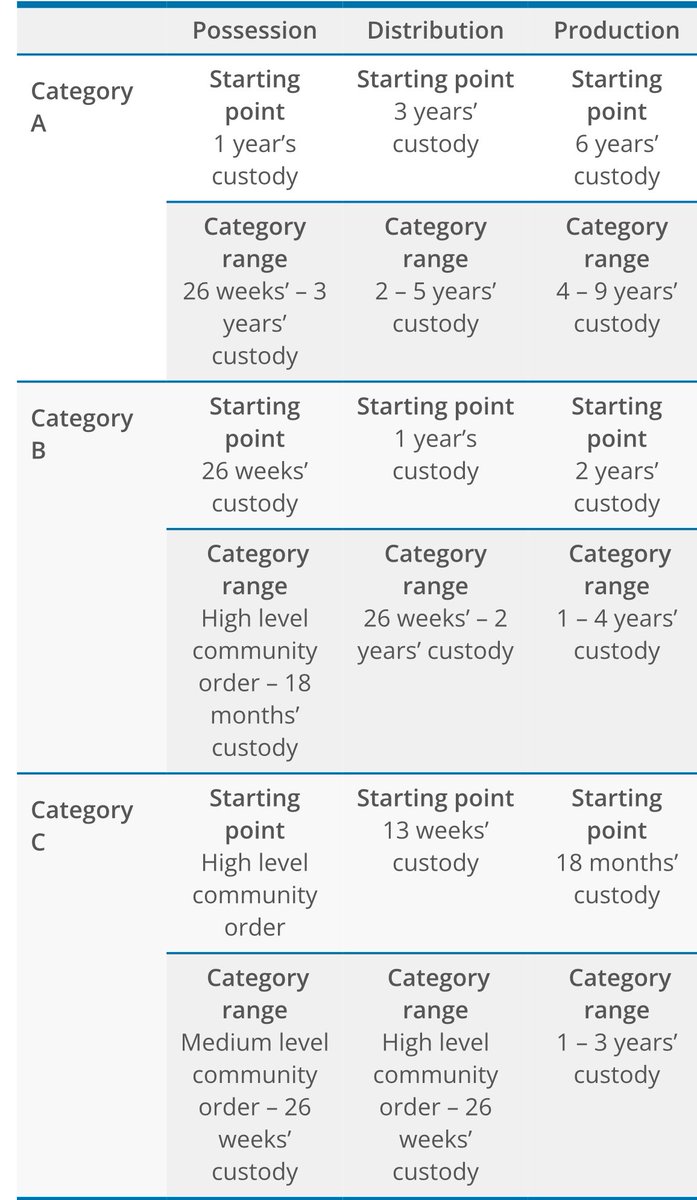

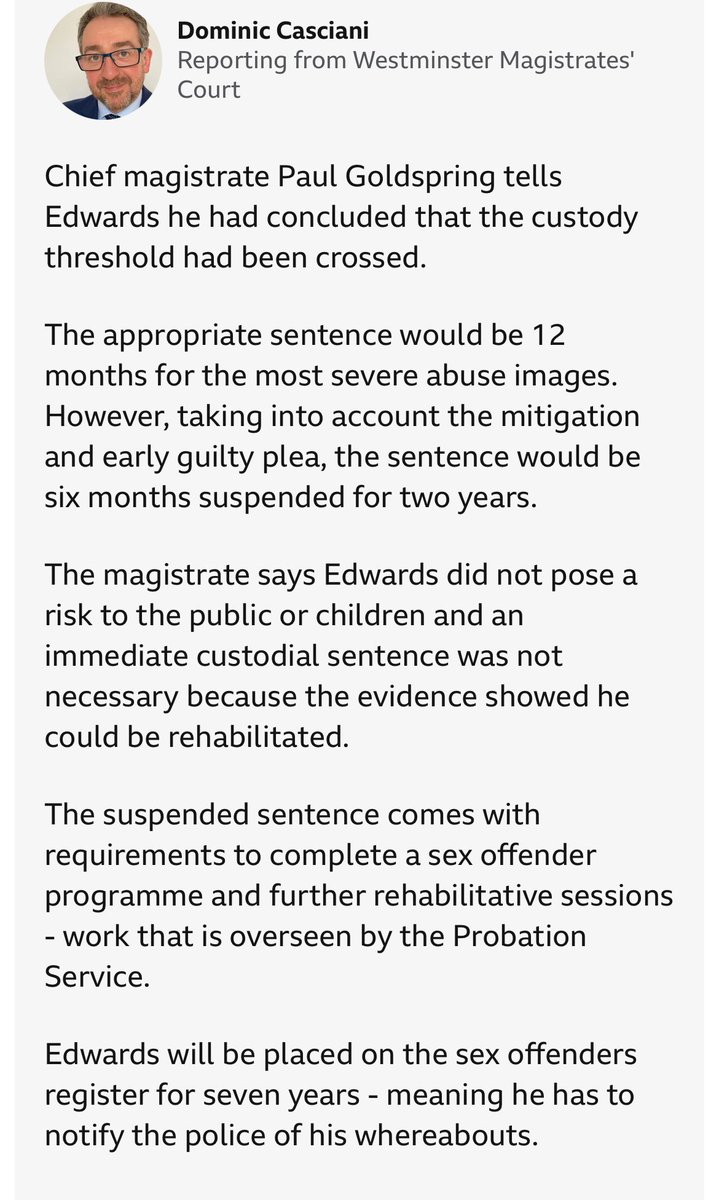

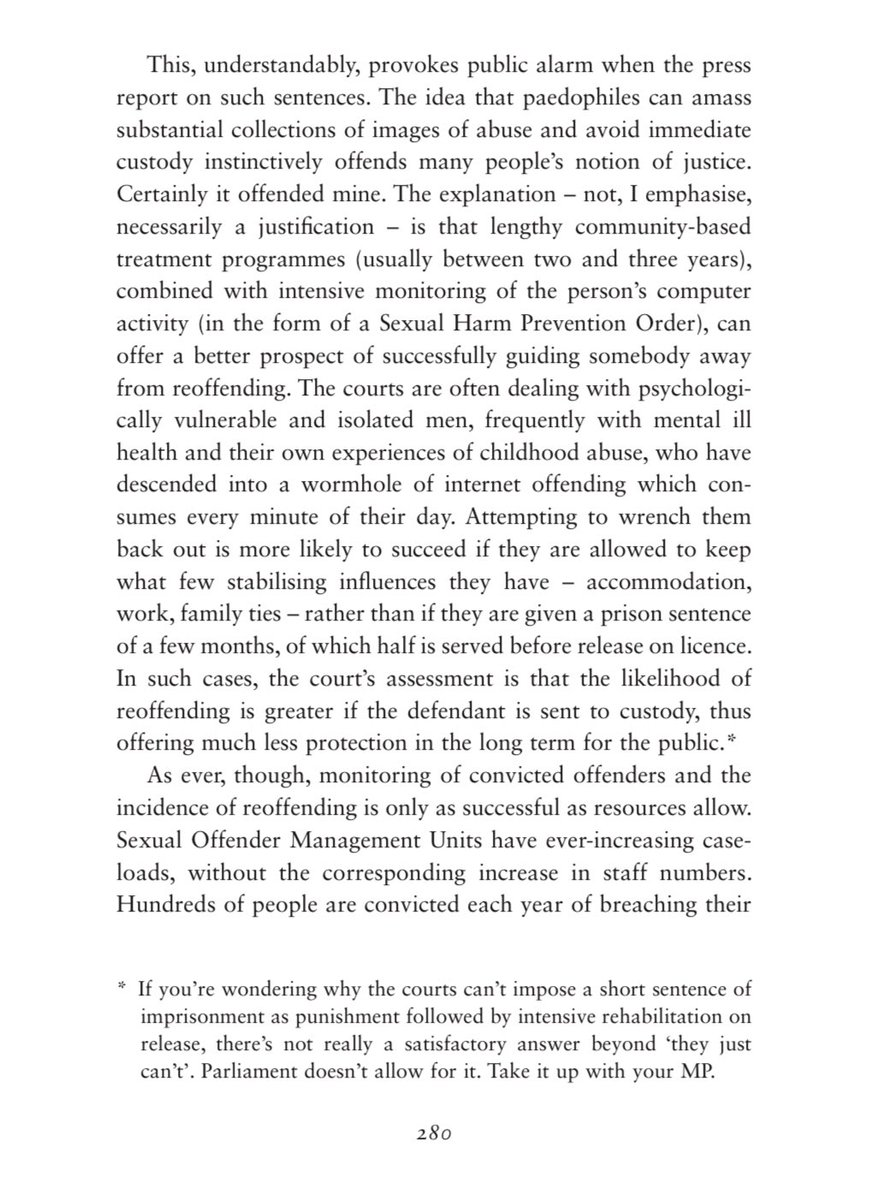

Once the court has established the category of images, the Guideline specifies sentence starting points and ranges.

Possessing Category A images (the most serious) carries a starting point of 1 year’s custody, with a range from 26 weeks to 3 years.

Possessing Category A images (the most serious) carries a starting point of 1 year’s custody, with a range from 26 weeks to 3 years.

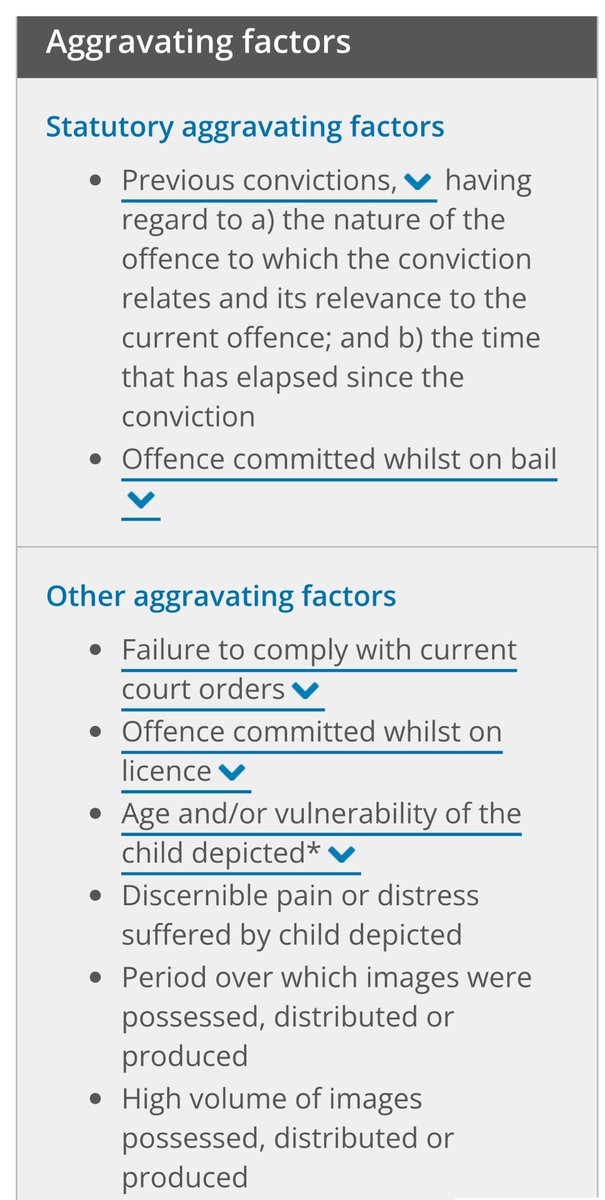

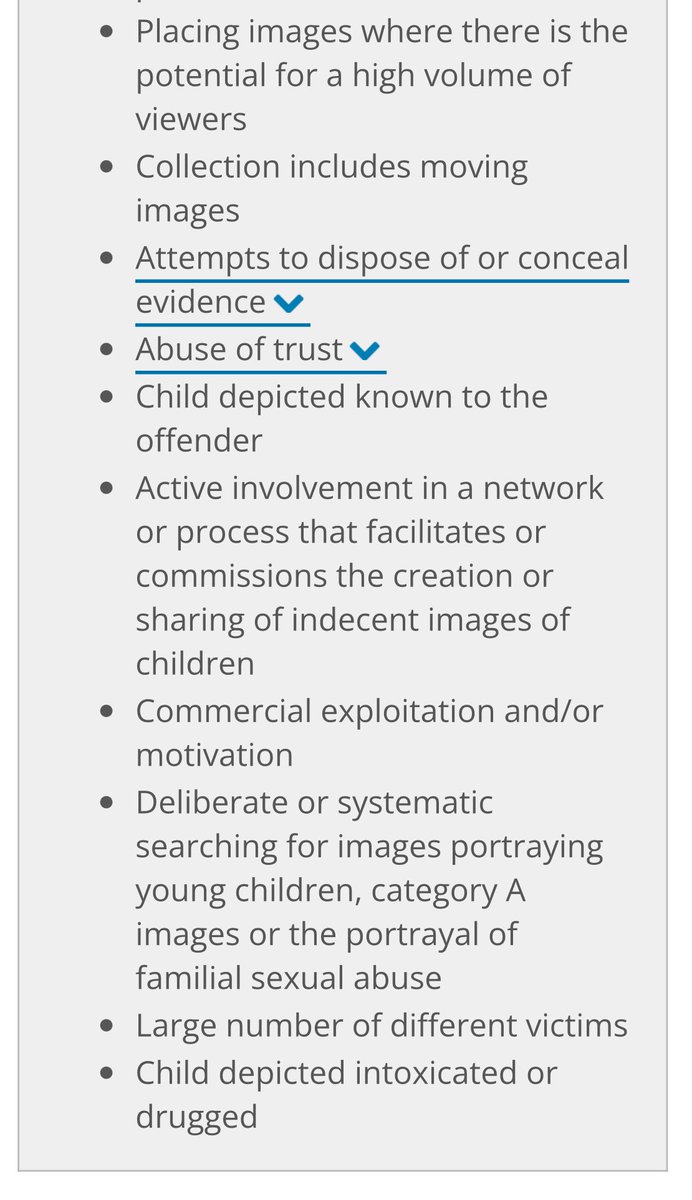

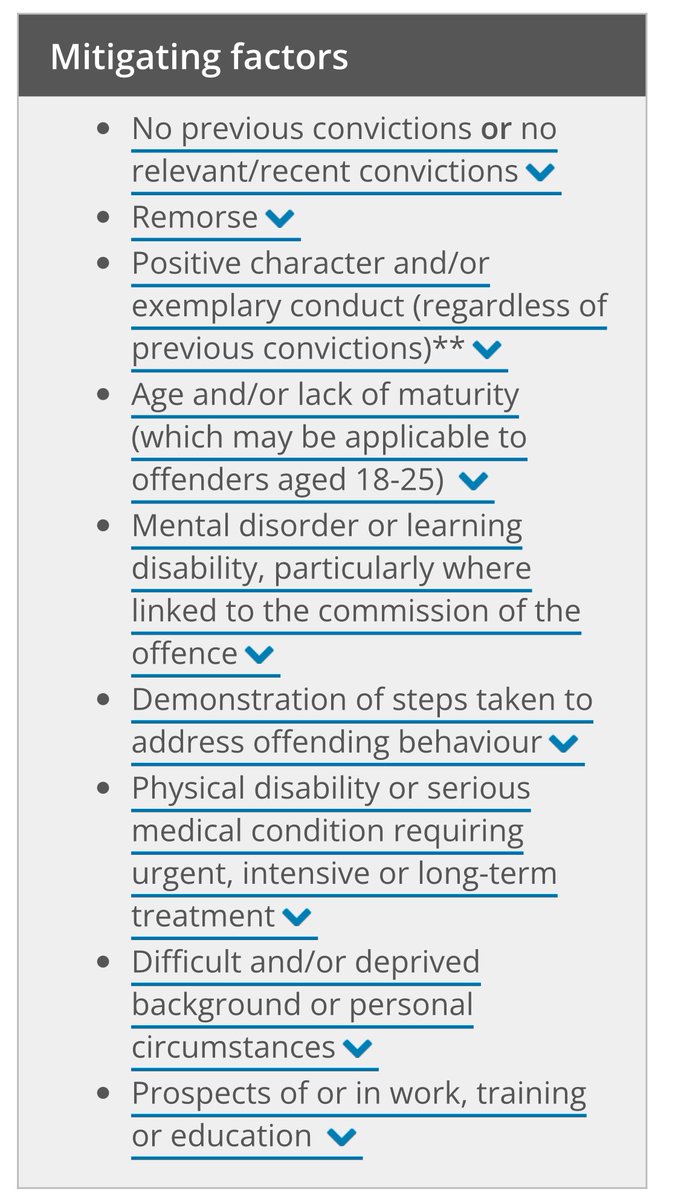

There are then lists of aggravating and mitigating factors, which can move that starting point up or down within the range:

A relevant feature in mitigation was Edwards’ mental health. There was evidence (expert reports) relating to this. And there is a separate Guideline- Sentencing offenders with mental disorders, developmental disorders, or neurological impairments: sentencingcouncil.org.uk/overarching-gu…

If the court finds that a mental disorder acted to mitigate an offender’s culpability (see the Guideline above for details), this may serve to reduce the sentence.

Because he pleaded guilty at the earliest opportunity, Edwards was entitled to one third off his sentence.

It seems that the judge took a starting point of 12 months, reduced to 9 months for mitigation, and reduced by a further third for guilty plea, to arrive at six months.

It seems that the judge took a starting point of 12 months, reduced to 9 months for mitigation, and reduced by a further third for guilty plea, to arrive at six months.

That of course is not the end of it.

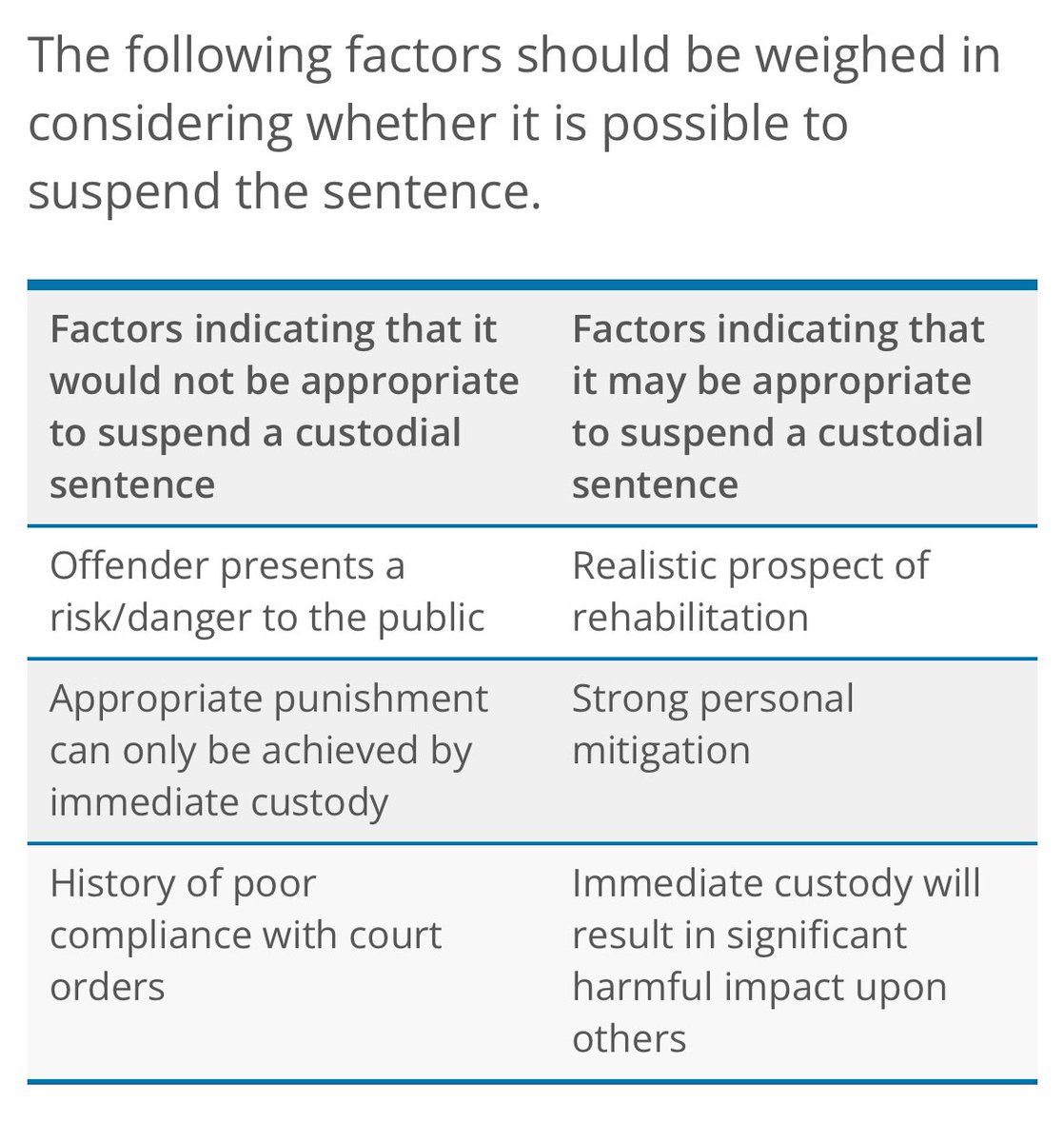

Any prison sentence of 2 years or less can be suspended. Under what circumstances? Yep, another Guideline I’m afraid, setting out factors for a court to consider.

sentencingcouncil.org.uk/overarching-gu…

Any prison sentence of 2 years or less can be suspended. Under what circumstances? Yep, another Guideline I’m afraid, setting out factors for a court to consider.

sentencingcouncil.org.uk/overarching-gu…

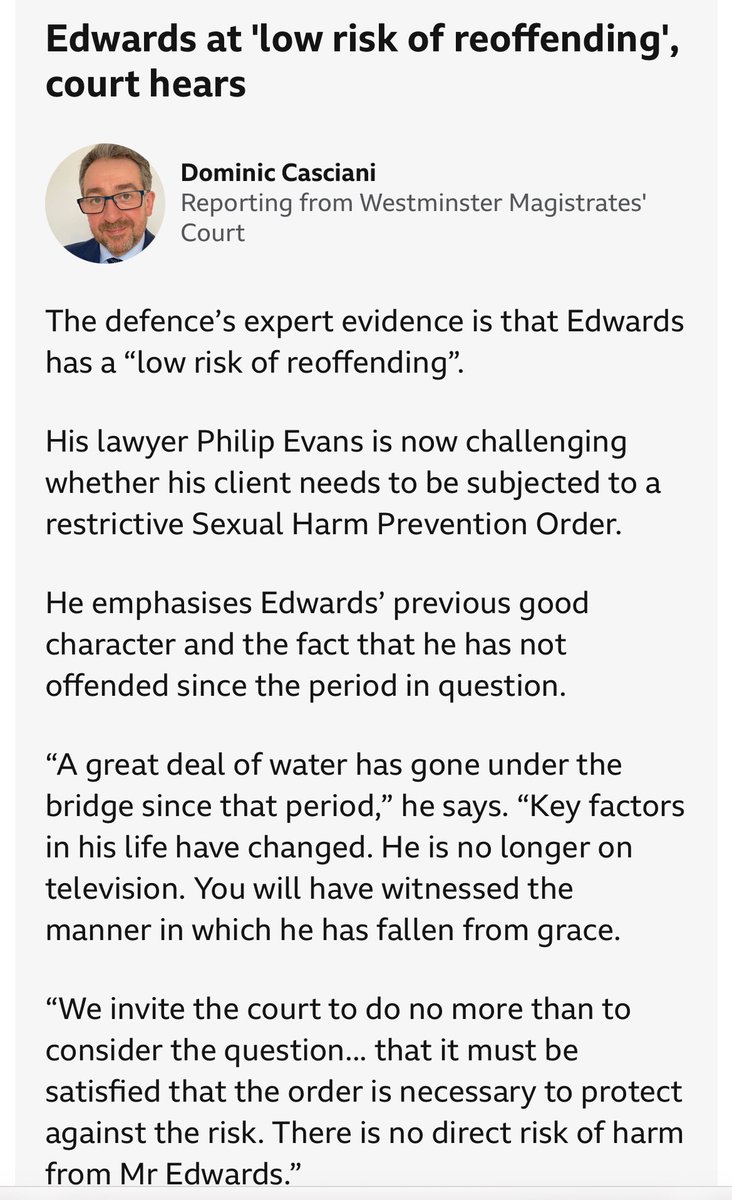

In Edwards’ case, he had been assessed by Probation (as most offenders are prior to sentence). He was apparently a low risk of reoffending. It was argued that he had strong personal mitigation.

Applying the Guideline, the judge suspended the sentence.

Applying the Guideline, the judge suspended the sentence.

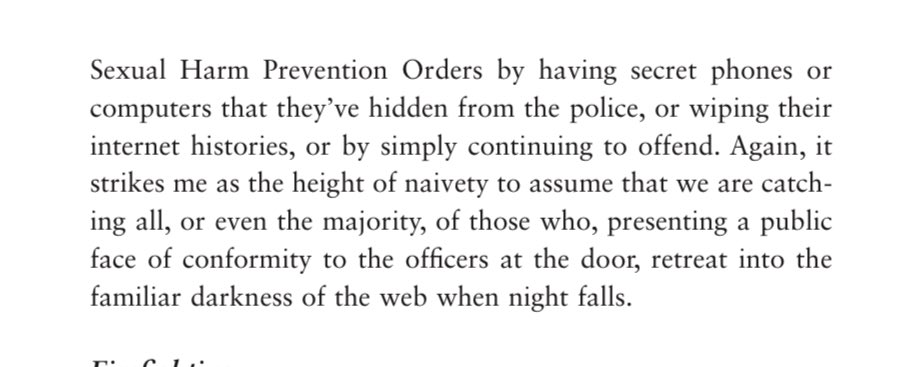

Now, as ever - and I cannot say this frequently or loudly enough - the fact that the Guidelines and the law have been followed does not, of course, mean people can’t reasonably disagree with the sentence.

Many will think offences of this type should always attract prison.

Many will think offences of this type should always attract prison.

However, the question has been raised as to whether Huw Edwards has received “special” or “two tier” treatment.

The answer is unequivocally “No”.

As somebody who has prosecuted and defended more of these cases than I can recall, this is the very outcome I would have expected.

The answer is unequivocally “No”.

As somebody who has prosecuted and defended more of these cases than I can recall, this is the very outcome I would have expected.

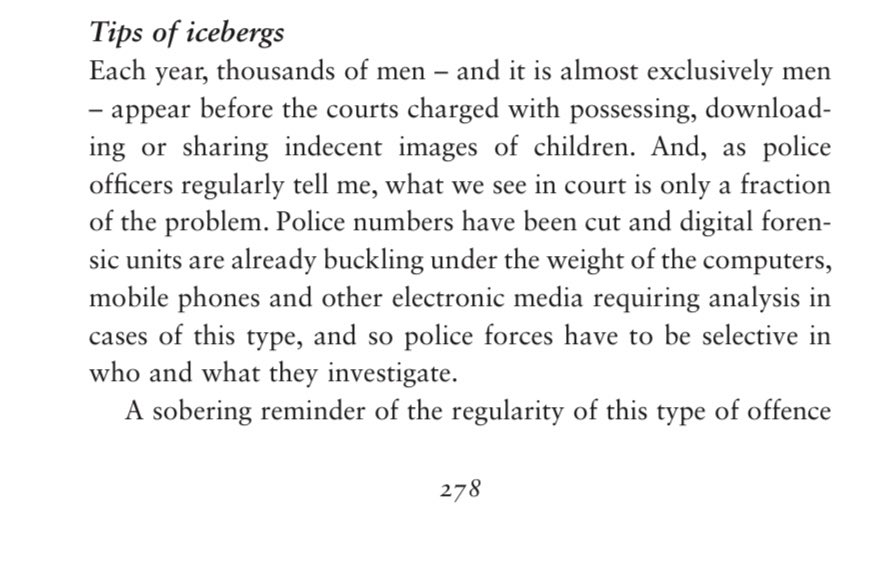

It is common for first-time offenders, even in cases as serious as this, to receive suspended sentences. Which many people outside the system understandably find shocking.

It’s something I’ve written about in #NothingButTheTruth

It’s something I’ve written about in #NothingButTheTruth

But special treatment? Two tier justice?

Absolute nonsense.

From all the information available, Huw Edwards has been treated exactly as any defendant in his position would expect to be treated.

Absolute nonsense.

From all the information available, Huw Edwards has been treated exactly as any defendant in his position would expect to be treated.

UPDATE:

Full sentencing remarks in the case of Huw Edwards are now available. Required reading for anybody expressing an opinion on this case. judiciary.uk/wp-content/upl…

Full sentencing remarks in the case of Huw Edwards are now available. Required reading for anybody expressing an opinion on this case. judiciary.uk/wp-content/upl…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh