When nuclear reactors are too blasé and you want to bend physics to your will…

Why not cool a reactor core with a fluid compressed & heated to such extremes that it's no longer a liquid or a gas but something else entirely.

It's the Supercritical Water Reactor thread!

Why not cool a reactor core with a fluid compressed & heated to such extremes that it's no longer a liquid or a gas but something else entirely.

It's the Supercritical Water Reactor thread!

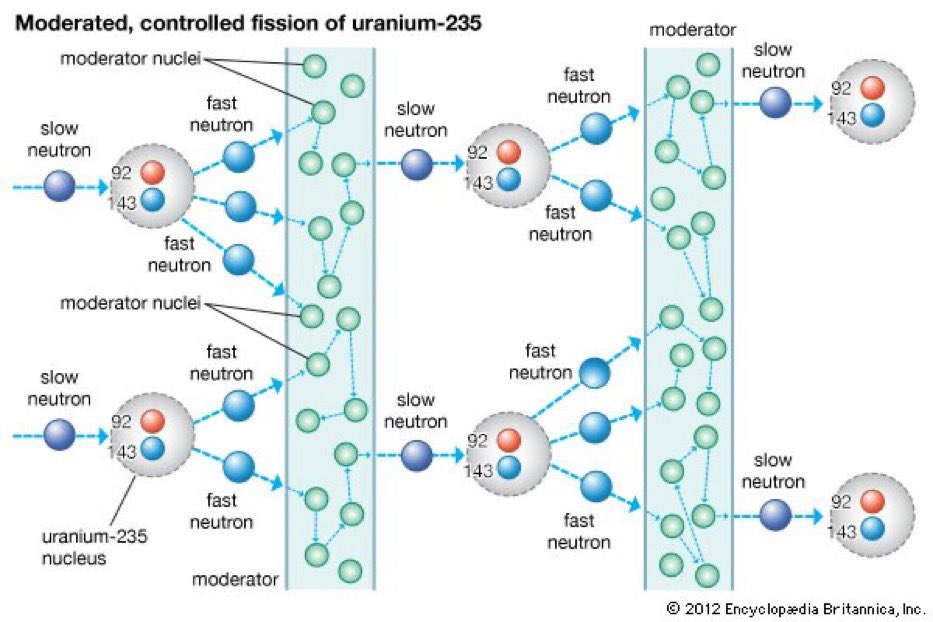

Most reactors in operation today are light water reactors, and there are good reasons for that: Water is both moderator & coolant, they have safe negative reactivity coefficients and decently high power density.

However they are complex and limited by temperature & efficiency.

However they are complex and limited by temperature & efficiency.

But you can cool a reactor core with many things: Water, carbon dioxide, liquid sodium, lead, helium, molten chloride salts… the list goes on.

Why not supercritical water?

And what's so special about supercritical water?

Why not supercritical water?

And what's so special about supercritical water?

Efficiency.

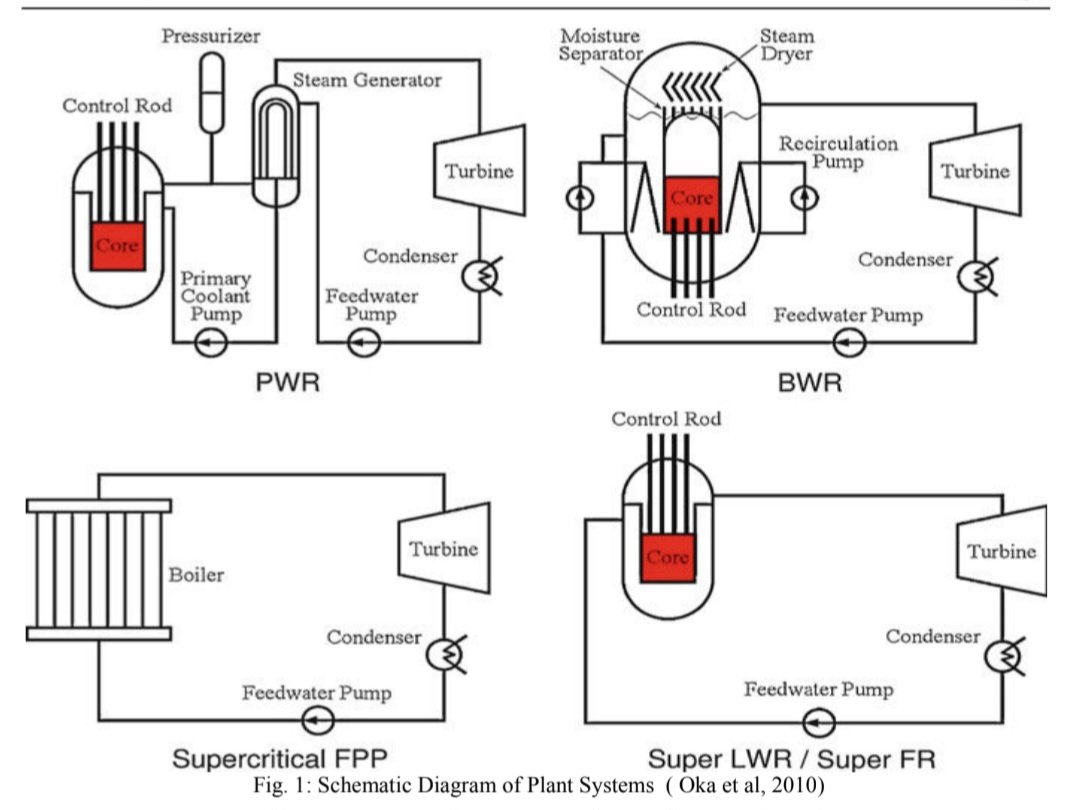

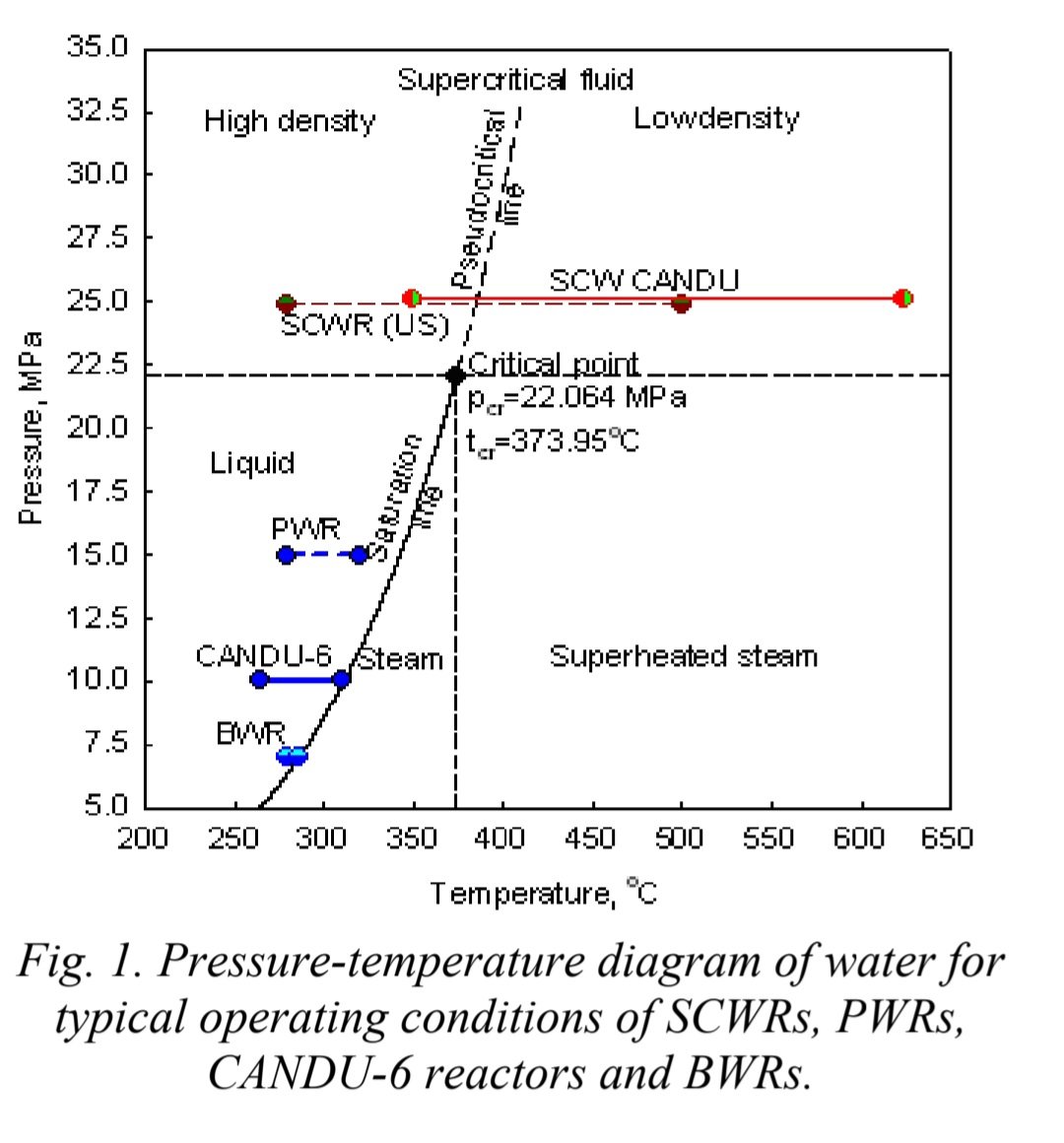

A normal pressurised water reactor (PWR) must keep a liquid phase throughout, meaning that even at 150 bar the core exit temperature is only 325 Celsius. In a boiling water reactor (BWR) that's 285 Celsius.

This means low thermal efficiency, of about 33%.

A normal pressurised water reactor (PWR) must keep a liquid phase throughout, meaning that even at 150 bar the core exit temperature is only 325 Celsius. In a boiling water reactor (BWR) that's 285 Celsius.

This means low thermal efficiency, of about 33%.

Complexity.

PWRs cannot boil and cannot run a turbine in their primary cycle, so a pressurizer and a secondary cycle are needed.

BWRs must protect the turbine from droplets, so superheaters and moisture separators are needed.

We can do better!

PWRs cannot boil and cannot run a turbine in their primary cycle, so a pressurizer and a secondary cycle are needed.

BWRs must protect the turbine from droplets, so superheaters and moisture separators are needed.

We can do better!

Supercritical water.

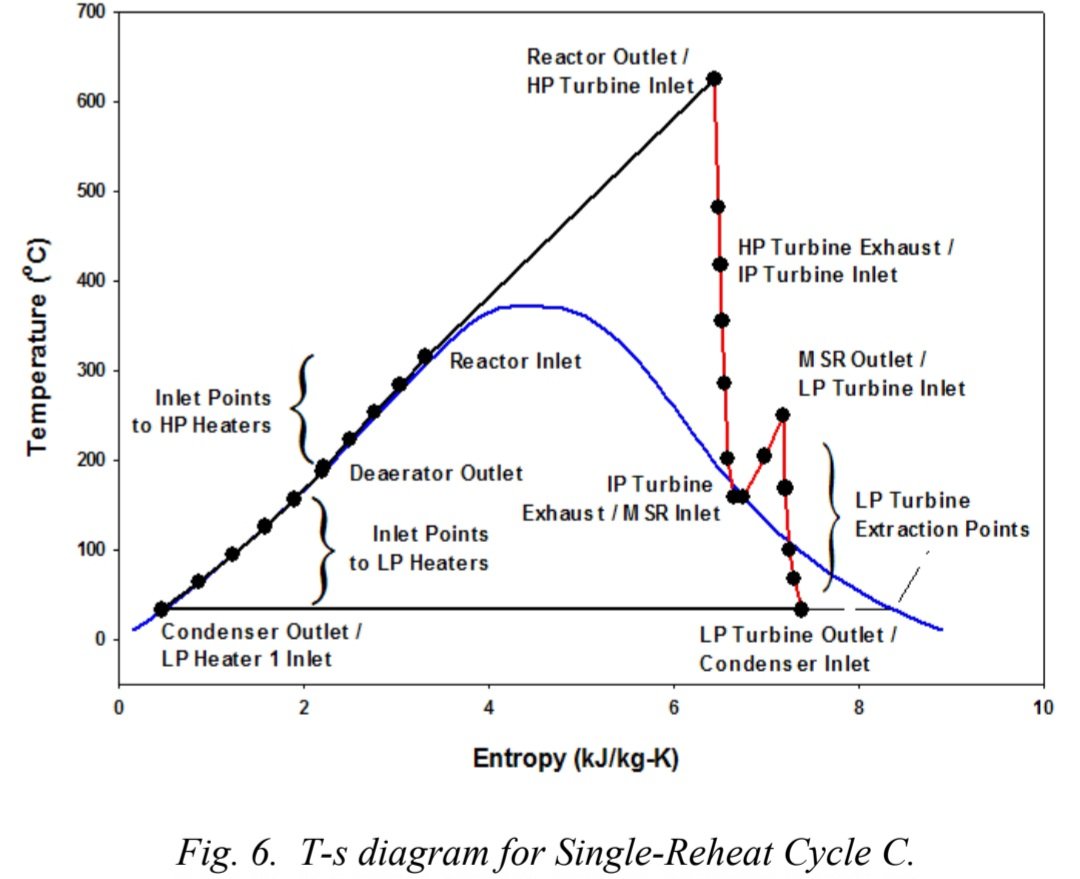

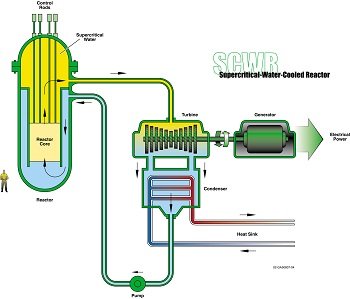

When water is over 374 Celsius and over 220 bar it becomes a supercritical (SC) fluid, containing properties of both gas and liquid, with no phase change as it heats but retaining high heat transfer.

A 675C core exit flow means 45%-50% thermal efficiency!

When water is over 374 Celsius and over 220 bar it becomes a supercritical (SC) fluid, containing properties of both gas and liquid, with no phase change as it heats but retaining high heat transfer.

A 675C core exit flow means 45%-50% thermal efficiency!

An SC cycle also allows direct flow from core to turbine and, unlike in a BWR, the homogenous flow doesn't need moisture separators: Simple!

That's not all: SC cycles need ⅛ the coolant of a water based system, are easy to pump & create fewer chaotic steam bubbles.

That's not all: SC cycles need ⅛ the coolant of a water based system, are easy to pump & create fewer chaotic steam bubbles.

It gets even better: Supercritical isn't even new!

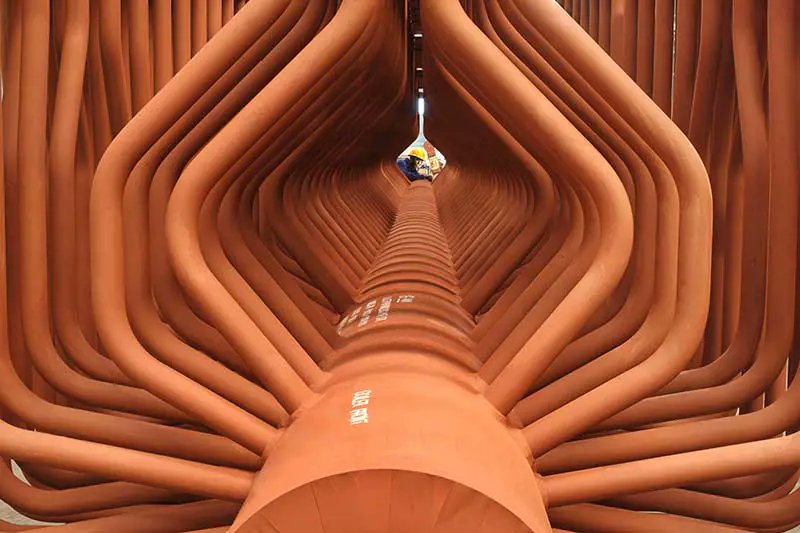

It's never been used in a reactor core, but it *is* used in power raising cycles in coal & gas power plants, and the structural & metallurgical demands in these applications are well understood.

It's never been used in a reactor core, but it *is* used in power raising cycles in coal & gas power plants, and the structural & metallurgical demands in these applications are well understood.

This all sounds lovely, but the old cynic's question applies:

“If they're so good, why aren't they everywhere?”

Let's explore that with a dive into the design…

“If they're so good, why aren't they everywhere?”

Let's explore that with a dive into the design…

Pressure vessel design.

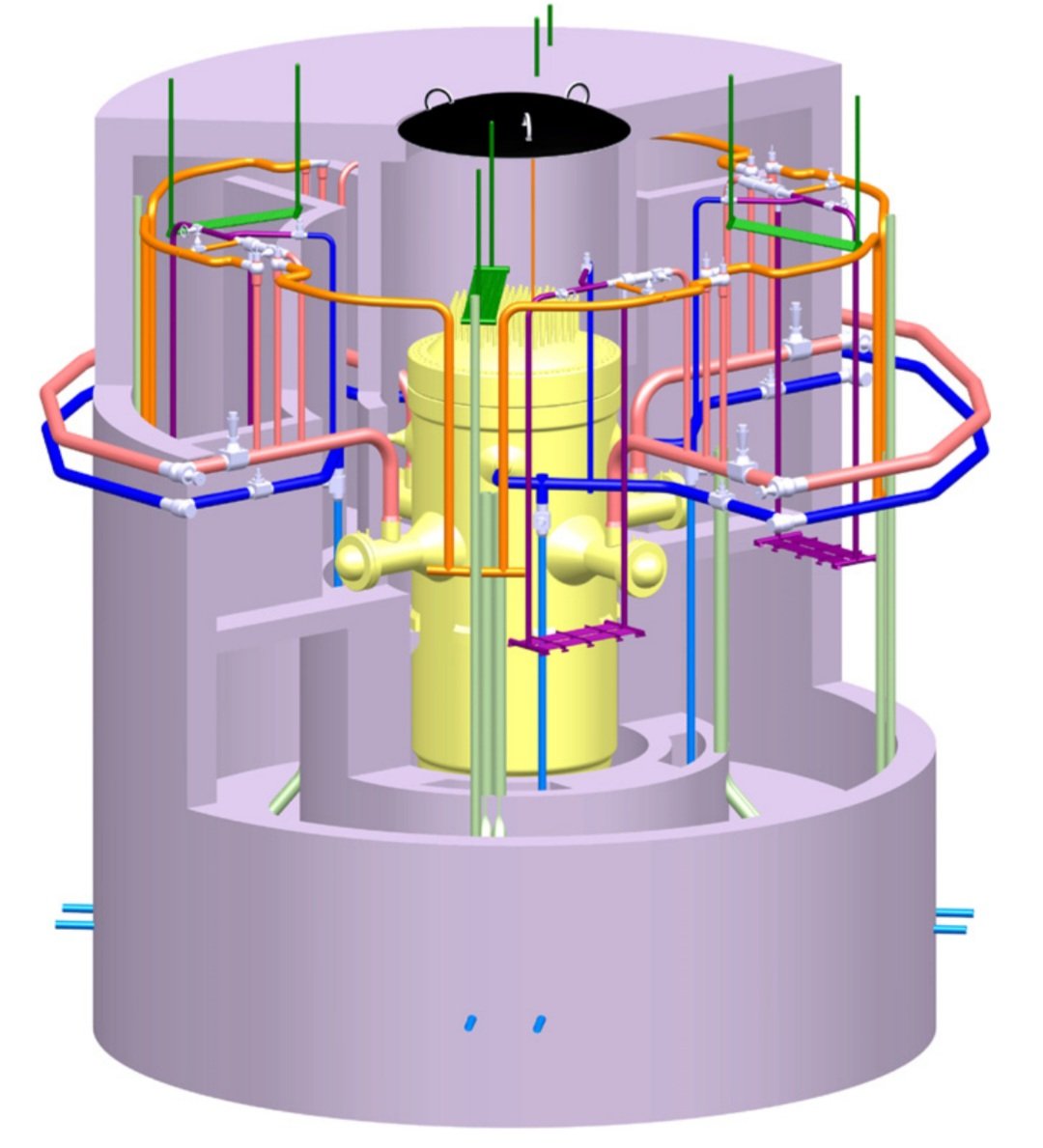

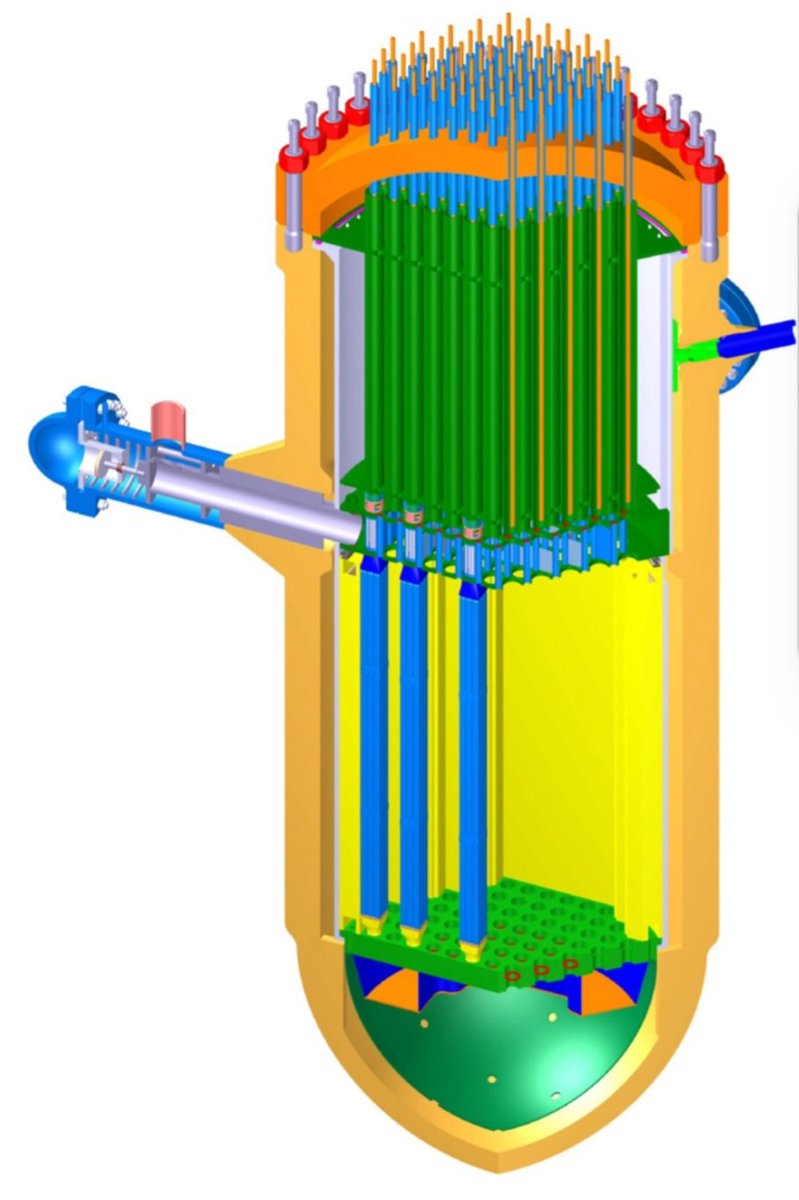

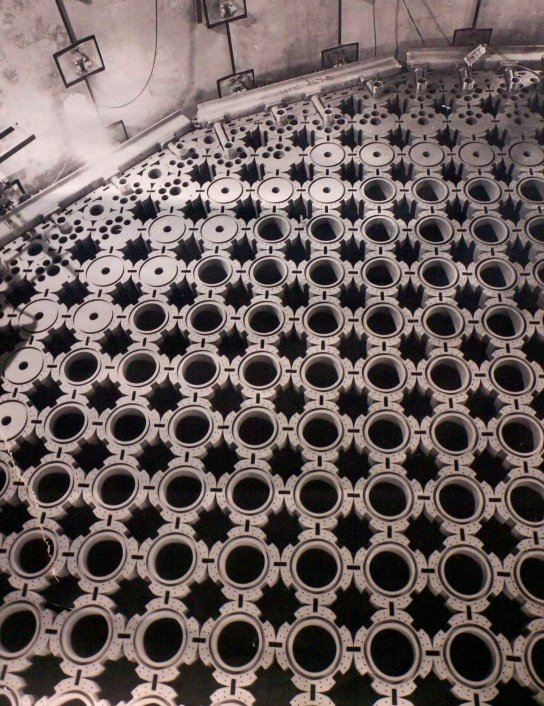

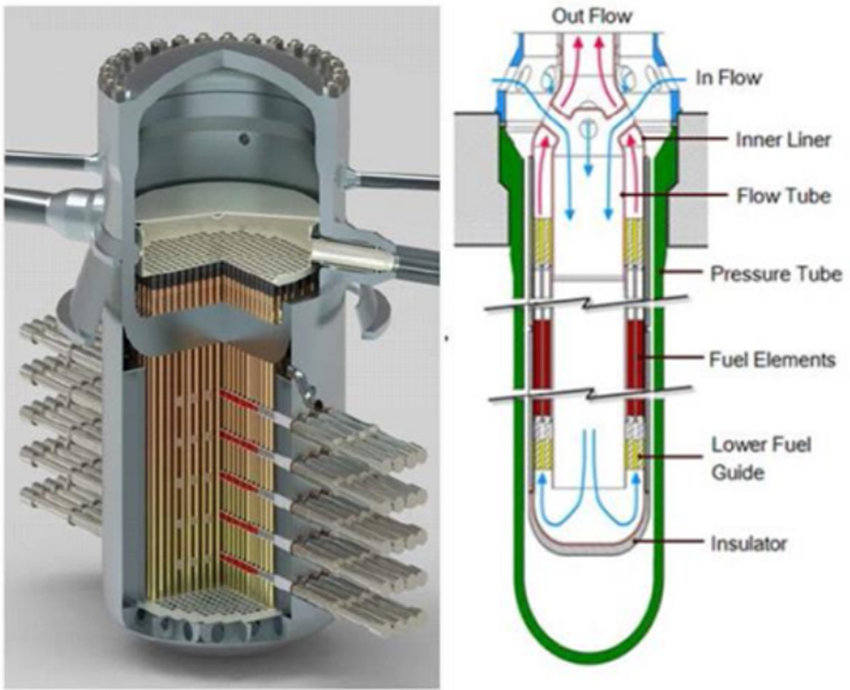

There are two ways to build a SCWR core: A pressure vessel, similar To a PWR/ BWR, or a calandria pressure tube design, similar to the Canadian CANDU.

With liquid water, pressure vessels are generally better, but SC coolant works well in either.

There are two ways to build a SCWR core: A pressure vessel, similar To a PWR/ BWR, or a calandria pressure tube design, similar to the Canadian CANDU.

With liquid water, pressure vessels are generally better, but SC coolant works well in either.

Heat exchanging.

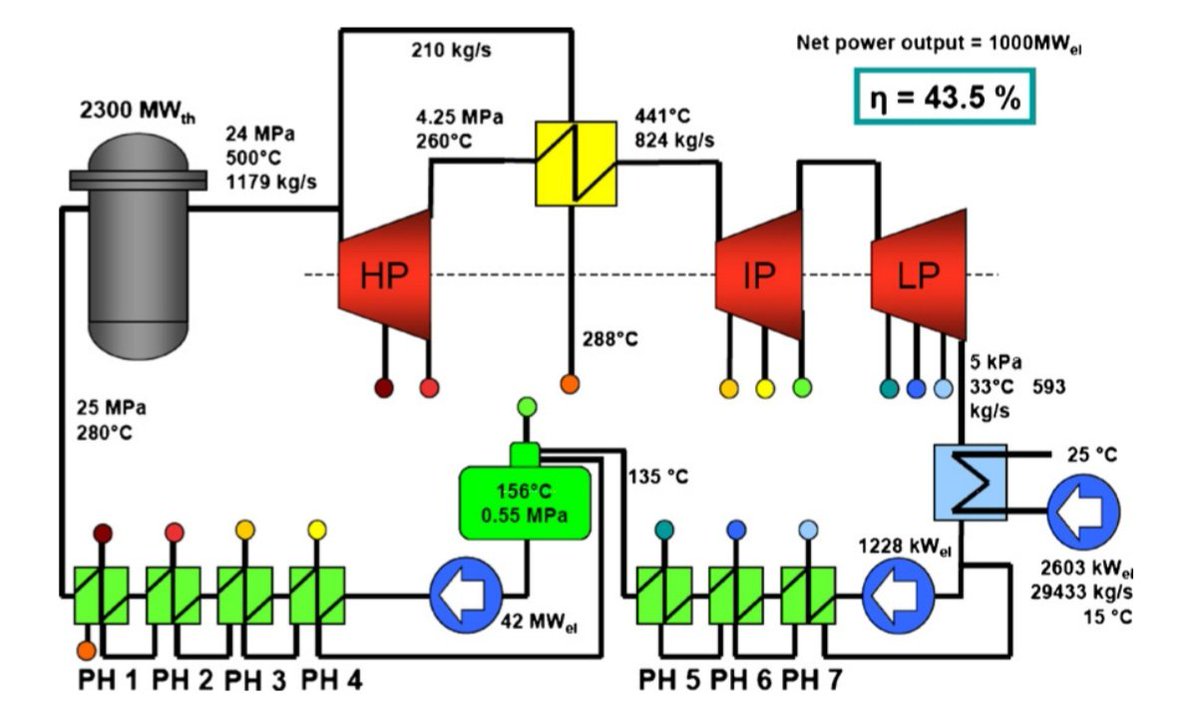

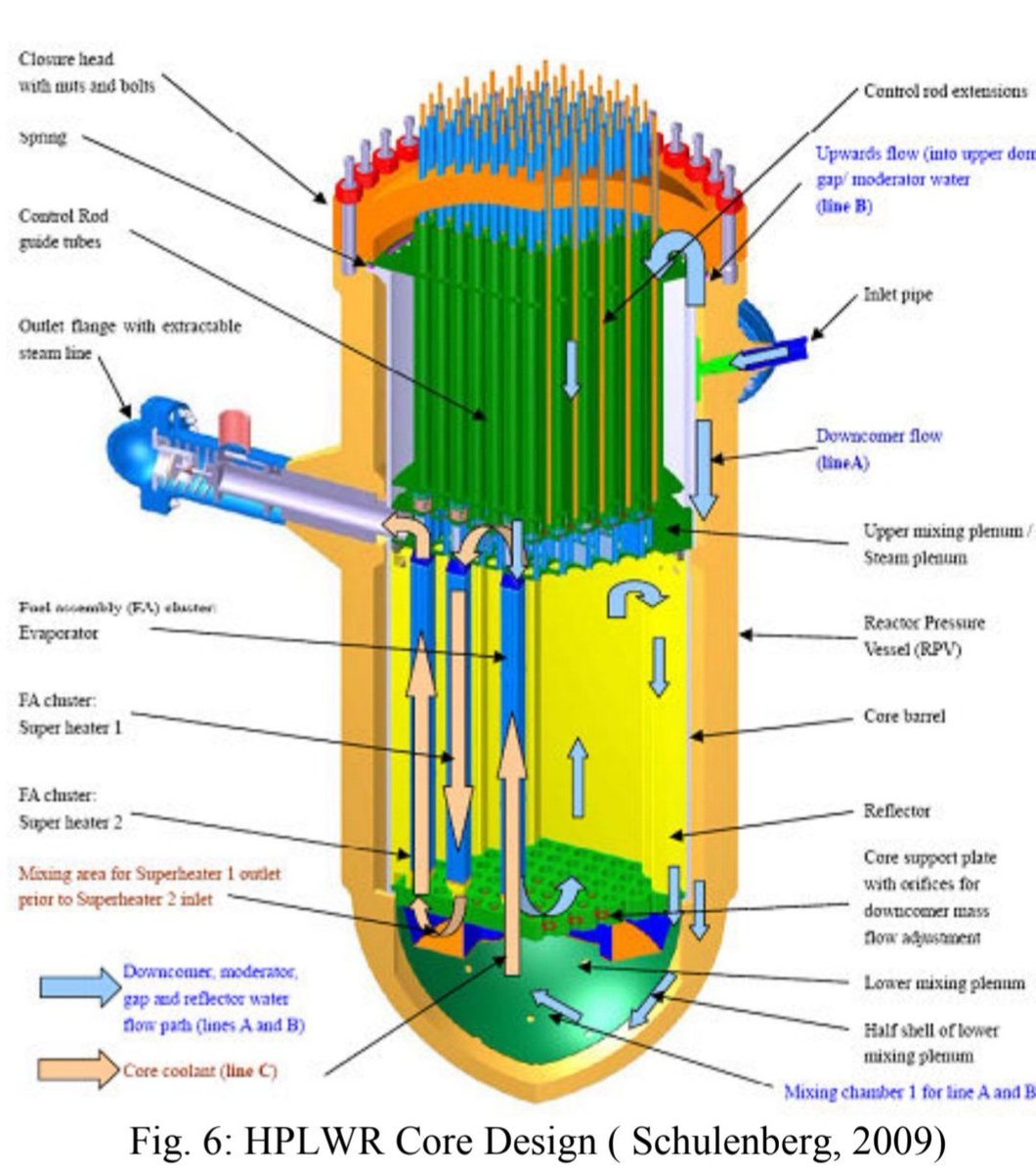

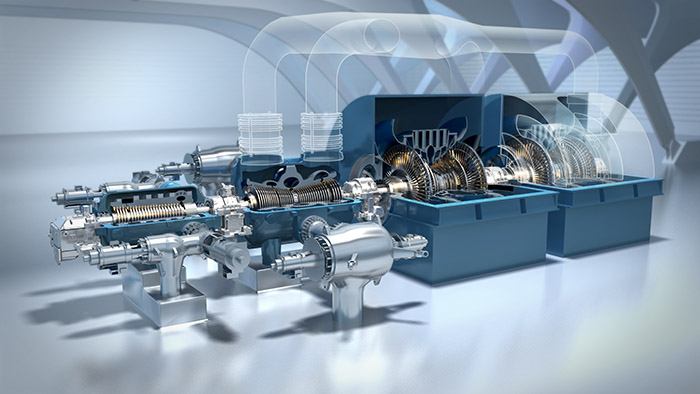

The simple process diagram shown earlier is idealised: In reality it would look a little something like this, with high & low pressure turbines and heat exchanging. Only the high pressure turbine is fully supercritical.

Why? A couple of reasons…

The simple process diagram shown earlier is idealised: In reality it would look a little something like this, with high & low pressure turbines and heat exchanging. Only the high pressure turbine is fully supercritical.

Why? A couple of reasons…

Firstly, there's advantage to using a rankine cycle where water moves between gas and liquid states: Liquid water is efficient to pump & pressurize, while gas is good at expansion in a turbine.

It does lose something in the transition however…

It does lose something in the transition however…

When water is boiling, energy is needed to turn it from a liquid to a gas: It's 1.5kJ/kg in a BWR and zero when supercritical. It's hard to fully recover.

Why not keep it supercritical throughout the cycle? This works poorly with water, but well with CO2

Why not keep it supercritical throughout the cycle? This works poorly with water, but well with CO2

https://x.com/Jordan_W_Taylor/status/1829542000284389526?t=PAj9A_trCmGu_MjqvQNwGw&s=19

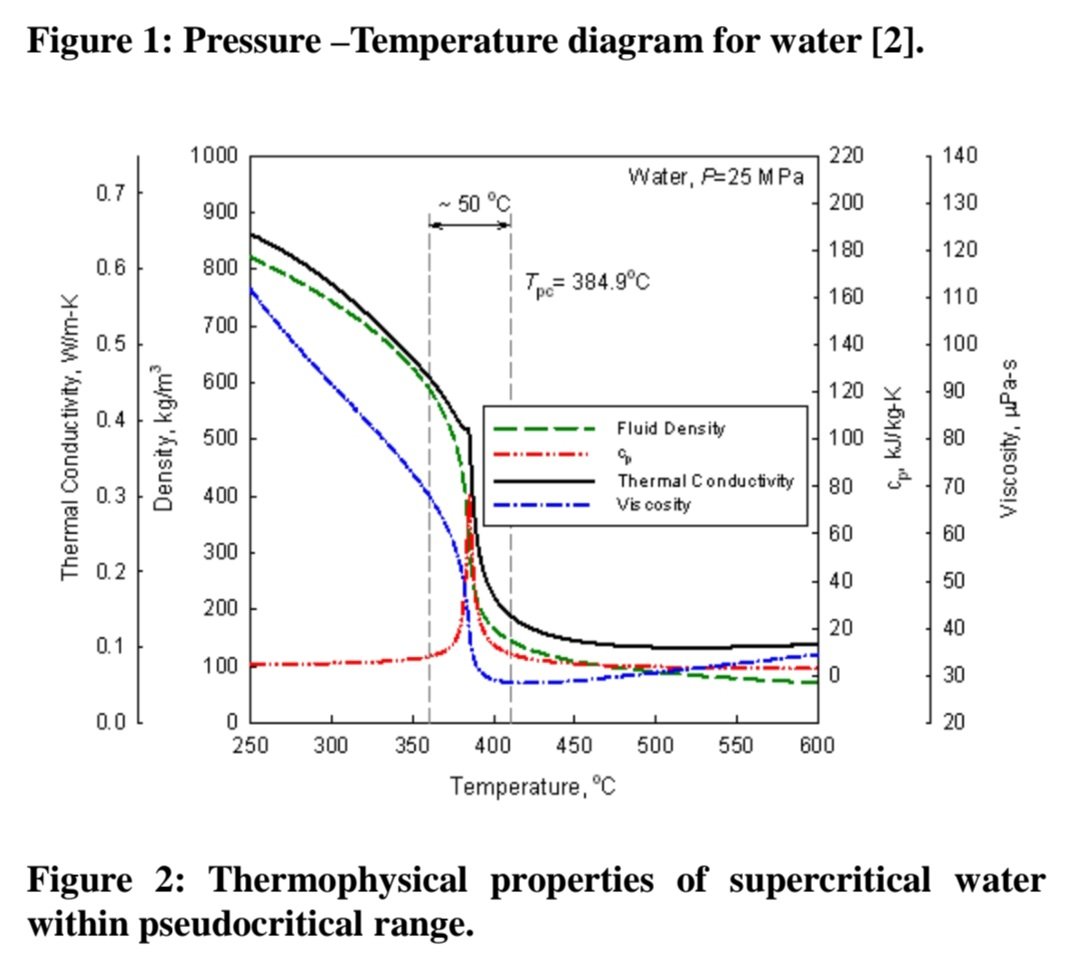

The other reason for reheat heat exchanging in a SCWR is to minimise the enthalpy change in the core.

Why?

Check out the density & thermal conductivity when it gets close to supercritical and remember this is in a core… Why add more change than is necessary?

Why?

Check out the density & thermal conductivity when it gets close to supercritical and remember this is in a core… Why add more change than is necessary?

Moderation.

In a classic light water reactor local boiling can produce similar effects, but that's mitigated as water is also the moderator, so density drops cause self-correcting reactivity drops too.

In a SCWR, the low density fluid makes it harder to use as moderator…

In a classic light water reactor local boiling can produce similar effects, but that's mitigated as water is also the moderator, so density drops cause self-correcting reactivity drops too.

In a SCWR, the low density fluid makes it harder to use as moderator…

…But not necessarily.

The European HPLWR design, for example, has a three-pass core water flow, only the last two of which are supercritical. This allows the coolant water to serve as moderator, in a fairly conservative design whose exit temperature is “only” 500 Celsius.

The European HPLWR design, for example, has a three-pass core water flow, only the last two of which are supercritical. This allows the coolant water to serve as moderator, in a fairly conservative design whose exit temperature is “only” 500 Celsius.

This is unusual, but it's implied by design: A SCWR has an enthalpy rise in the core about ten times a pressurised water reactor, so without multiple passes either the core grows vertically or new high temp cladding materials are needed.

There are other challenges…

There are other challenges…

One of the design challenges of SCWRs is how to manage hot spots and local heating when transitioning to supercritical inside the core.

Ridged or finned cladding such as found in CO2 cooled reactors could be beneficial by enhancing flow mixing and damping excursions.

Ridged or finned cladding such as found in CO2 cooled reactors could be beneficial by enhancing flow mixing and damping excursions.

Corrosion.

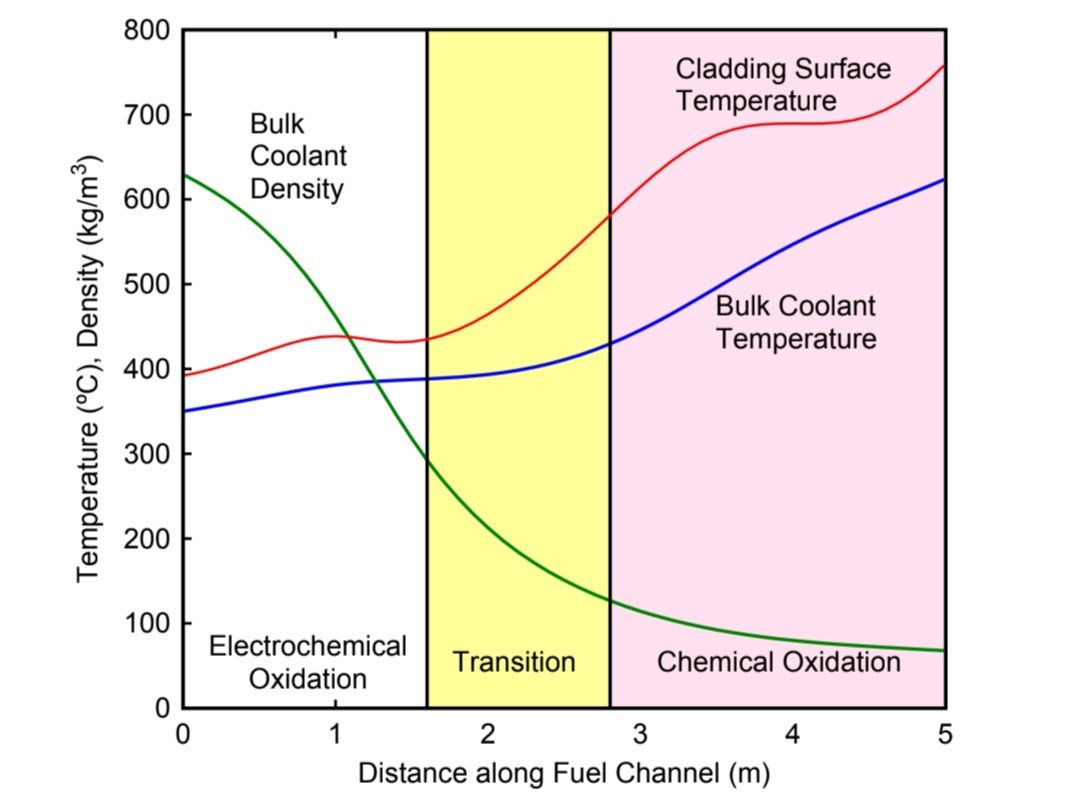

In liquid water, electrochemical oxidisation corrosion dominates. In supercritical steam, local chemical oxidisation dominates. In the transition phase both may play a part. On top of stress corrosion cracking and neutron bombardment in the core, this needs research.

In liquid water, electrochemical oxidisation corrosion dominates. In supercritical steam, local chemical oxidisation dominates. In the transition phase both may play a part. On top of stress corrosion cracking and neutron bombardment in the core, this needs research.

Core behaviour.

Managing a reactor core through multiple phase transitions, particularly in power-up and power-down scenarios, poses challenges with SCWRs when fluid density starts to change rapidly through transition points. Feedback loops must be understood and prevented.

Managing a reactor core through multiple phase transitions, particularly in power-up and power-down scenarios, poses challenges with SCWRs when fluid density starts to change rapidly through transition points. Feedback loops must be understood and prevented.

Is it worth the challenge?

It would mean more efficiency, a simpler primary cycle, smaller turbines, smaller containment and process heat export.

Get the balance right and it might mean cheaper nuclear power, but first we need to tame an SC water cooled core!

It would mean more efficiency, a simpler primary cycle, smaller turbines, smaller containment and process heat export.

Get the balance right and it might mean cheaper nuclear power, but first we need to tame an SC water cooled core!

The SCWR must compete with lead, sodium and other reactors, as well as time-worn, fleet delivered GenIII designs, and of course other clean power sources.

It has bags of potential, but first it must understand its own heart,

-Which might be an affair worth having.

It has bags of potential, but first it must understand its own heart,

-Which might be an affair worth having.

Supercritical water… like many new energy concepts it's a bit unearthly.

But powerful nevertheless!

To learn more about the GenIV reactor concepts, and many other things, scroll through the highlights tab on my profile.

Articles used are shown, I hope you enjoyed this!

But powerful nevertheless!

To learn more about the GenIV reactor concepts, and many other things, scroll through the highlights tab on my profile.

Articles used are shown, I hope you enjoyed this!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh