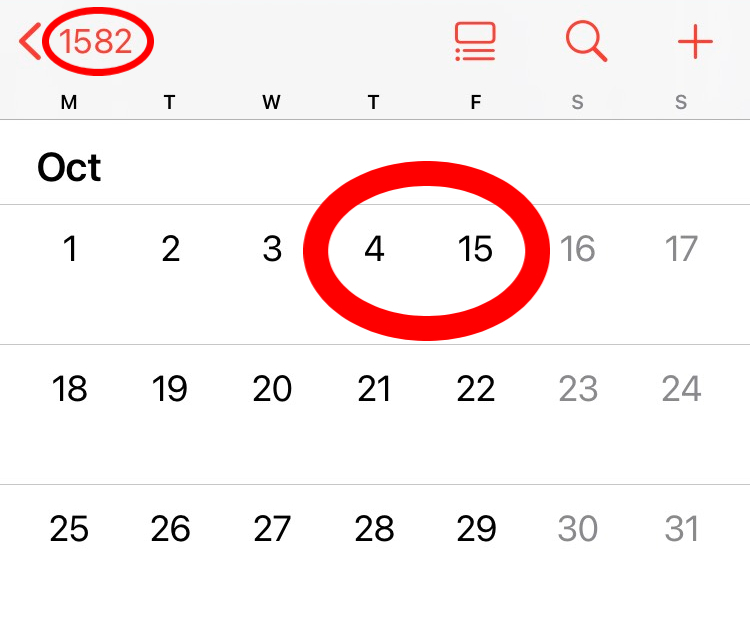

In the year 1582 something strange happened.

Thursday 4th October was followed immediately by Friday 15th October.

This is the story of history's 10 missing days...

Thursday 4th October was followed immediately by Friday 15th October.

This is the story of history's 10 missing days...

And it begins with Julius Caesar.

The year was 46 BC and he had just become "Dictator for Life" — Caesar was the sole ruler of Rome.

Among the many problems he needed to solve was the Roman Calendar, which had fallen into total chaos.

The year was 46 BC and he had just become "Dictator for Life" — Caesar was the sole ruler of Rome.

Among the many problems he needed to solve was the Roman Calendar, which had fallen into total chaos.

See, the old Roman Calendar was 355 days long.

To keep it in alignment with the solar year — how long it takes the Earth to orbit the Sun — extra "intercalary" months of 22 or 23 days were added every two years.

That made sure the calendar was synchronised with the seasons.

To keep it in alignment with the solar year — how long it takes the Earth to orbit the Sun — extra "intercalary" months of 22 or 23 days were added every two years.

That made sure the calendar was synchronised with the seasons.

But during the wars and civil strife of the 1st century BC these intercalary months had not been added properly, and the old calender had fallen badly out of sync with the solar year.

Caesar consulted Rome's best astronomers and came up with a solution — the Julian Calendar.

Caesar consulted Rome's best astronomers and came up with a solution — the Julian Calendar.

This new Julian Calendar was based on the idea that a solar year is 365.25 days long.

Each calendar year would have 365 days, and every four years — what we call a leap year — an extra day would be added at the end of February.

A simpler and far more effective system.

Each calendar year would have 365 days, and every four years — what we call a leap year — an extra day would be added at the end of February.

A simpler and far more effective system.

To make sure his new calendar started at the right point, Caesar had to add two extra months to 46 BC.

And so 46 BC was, bizarrely, 445 days long — officially the longest year in history.

Little wonder it was known as the "annus confusionis", or "year of confusion".

And so 46 BC was, bizarrely, 445 days long — officially the longest year in history.

Little wonder it was known as the "annus confusionis", or "year of confusion".

But there was a problem with the Julian Calendar.

It worked on the basis that a year is 365.25 days long... but a year is actually 365.2422 days long.

This meant the Julian Calendar drifted one day out of alignment with the solar year every century or so.

It worked on the basis that a year is 365.25 days long... but a year is actually 365.2422 days long.

This meant the Julian Calendar drifted one day out of alignment with the solar year every century or so.

That sounds minor, but the Julian Calendar was used for over 1,600 years.

And so by the 16th century it had drifted 14 days out of sync with the solar year.

This meant that (among other things) Easter wasn't being celebrated on the correct date — a fact considered unacceptable.

And so by the 16th century it had drifted 14 days out of sync with the solar year.

This meant that (among other things) Easter wasn't being celebrated on the correct date — a fact considered unacceptable.

Scholars and clerics had been agitating for reform for decades — even during the Dark Ages people had noticed that the Julian Calendar meant Easter wasn't being observed at the right time.

So, in 1582, Pope Gregory XIII finally decided to solve this problem.

So, in 1582, Pope Gregory XIII finally decided to solve this problem.

Under Gregory the leading astronomers and mathematicians of the era produced a new, modified version of the Julian Calendar.

The major difference was that no century year would be a leap year unless divisible by 400 (e.g. 2000).

This prevented the one-day drift every century.

The major difference was that no century year would be a leap year unless divisible by 400 (e.g. 2000).

This prevented the one-day drift every century.

The calendar also needed resetting.

And, crucially, Gregory reset it to the time of the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD, when the method for dating Easter was established — rather than to the birth of Christ or creation of the Julian Calendar.

So 10 days, not 14, had to be removed.

And, crucially, Gregory reset it to the time of the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD, when the method for dating Easter was established — rather than to the birth of Christ or creation of the Julian Calendar.

So 10 days, not 14, had to be removed.

And in 1582 Gregory issued a decree called "Inter gravissimas".

It stated that the new, modified version of the Julian Calendar was to be adopted that year.

The change would happen in October, when Thursday 4th would be followed by Friday 15th, to correct the 10 days of drift.

It stated that the new, modified version of the Julian Calendar was to be adopted that year.

The change would happen in October, when Thursday 4th would be followed by Friday 15th, to correct the 10 days of drift.

This change was immediately adopted in the Papal States, the Italian states, Spain, Portugal, and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

In France it was adopted in December — the 9th was followed by the 20th — and by 1584 all of Catholic Europe was using the Gregorian Calendar.

In France it was adopted in December — the 9th was followed by the 20th — and by 1584 all of Catholic Europe was using the Gregorian Calendar.

But Europe was split religiously — both Protestant and Orthodox countries saw Gregory's new calendar as fundamentally Catholic and therefore resisted it.

And so, for a time, crossing the border from one country to another could also involve going forward or backward 10 days.

And so, for a time, crossing the border from one country to another could also involve going forward or backward 10 days.

By the 18th century, however, it had become clear that the Gregorian Calendar's accuracy made it better than the Julian Calendar.

Prussia was the first Protestant state to switch over, followed by Denmark-Norway, the Protestant Netherlands, Switzerland, and others.

Prussia was the first Protestant state to switch over, followed by Denmark-Norway, the Protestant Netherlands, Switzerland, and others.

The United Kingdom only adopted the Gregorian Calendar in 1752, and the Act of Parliament introducing it made no mention of Gregory whatsoever.

By that point another day had drifted, and so 11 days had to be removed — in 1752 the 2nd September was followed by 14th September.

By that point another day had drifted, and so 11 days had to be removed — in 1752 the 2nd September was followed by 14th September.

That same Act also changed the start of the United Kingdom's legal year from 25th March to 1st January, in keeping with the rest of Europe.

And that explains why England's tax year still ends on 5th April — 11 days after 25th March.

A peculiar historical relic.

And that explains why England's tax year still ends on 5th April — 11 days after 25th March.

A peculiar historical relic.

Other countries were even slower — in Russia the Gregorian Calendar wasn't adopted until 1918.

Hence the famous confusion around the "October Revolution" of 1917.

It happened on 25th October in the Julian Calendar, but on 7th November in the Gregorian.

Hence the famous confusion around the "October Revolution" of 1917.

It happened on 25th October in the Julian Calendar, but on 7th November in the Gregorian.

Although the Gregorian is now the world's most widely used calendar, plenty of others are used for religious or traditional purposes.

Like the Islamic Hijri calendar, the Japanese regnal calendar, or even the old Julian Calendar, which is still used in Orthodox Christianity.

Like the Islamic Hijri calendar, the Japanese regnal calendar, or even the old Julian Calendar, which is still used in Orthodox Christianity.

All these different calendars — along with removing days and changing the start of the new year — can make dating historical events strangely difficult.

And the further back in time you go, the more complicated it gets.

"When did that happen?" is not a simple question.

And the further back in time you go, the more complicated it gets.

"When did that happen?" is not a simple question.

For example, William Shakespeare was born on 23rd April 1564 according to the Julian Calendar — but on 3rd May according to the (retrospectively applied) Gregorian Calendar.

When the Gregorian Calendar is extended backward in time it is called the "Proleptic Gregorian Calendar".

When the Gregorian Calendar is extended backward in time it is called the "Proleptic Gregorian Calendar".

In any case, that's the story of why October 4th 1582 was followed by October 15th.

That days can be removed from (or added to) the calendar is a wonderful reminder of our strange relationship with time, of how some things which seem permanent — like the date — really aren't.

That days can be removed from (or added to) the calendar is a wonderful reminder of our strange relationship with time, of how some things which seem permanent — like the date — really aren't.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh