On this day in 1971, Simone Langenhoff, aged 6, was killed while cycling to school; hit by a speeding driver.

Her death and the movement started by her father, Vic Langenhoff, a newspaper journalist, changed an entire country and saved thousands of Dutch lives. Here's how 🧵

Her death and the movement started by her father, Vic Langenhoff, a newspaper journalist, changed an entire country and saved thousands of Dutch lives. Here's how 🧵

He joined other grieving parents to campaign for change. Vic Langenhoff wrote this in his newspaper in September 1972: “A few people have stood up who want to break through the apathy with which Dutch people accept the daily slaughter of children in traffic.”

He published a manifesto for change: “I am not advocating for 22-lane highways, but for safe cycle paths.”

He also highlighted the need for tougher driving penalties and reminded readers that driving is not a fundamental human right.

He also highlighted the need for tougher driving penalties and reminded readers that driving is not a fundamental human right.

The number of traffic casualties in the Netherlands rose to a peak of 3,300 deaths in 1971.

More than 400 children were killed in traffic collisions that year; Simone Langenhoff one of them. Each death meant families and communities torn apart.

More than 400 children were killed in traffic collisions that year; Simone Langenhoff one of them. Each death meant families and communities torn apart.

Vic Langenhoff’s article struck a chord which led to the formation of Stop de Kindermoord. First led by Maartje van Putten, a former MEP, she told The Guardian: “The streets no longer belonged to the people who lived there, but to huge traffic flows. That made me very angry.”

You can watch a brilliant piece and interview with Maartje van Putten from @annaholligan here:

Politics was more accessible in the 1970s. The group held demonstrations, created play streets and visited politicians. They met MPs and cycled to the house of the Prime Minister, Joop den Uyl, asking for streets to be safer for children. The PM came out to hear their plea.

Protests were continued and vocal. Politicians were deeply worried about road deaths on their streets.

The Dutch government supported the group and eventually they started to produce ideas for safer streets and more inclusive urbanism.

The Dutch government supported the group and eventually they started to produce ideas for safer streets and more inclusive urbanism.

Progress started to happen, aided by the 1973 OAPEC Oil Embargo, which encouraged the Dutch back onto their bikes.

The Government started "Car Free Sundays".

The protests and world events led to the development of the first dedicated cycle routes in the late 1970s.

The Government started "Car Free Sundays".

The protests and world events led to the development of the first dedicated cycle routes in the late 1970s.

The Dutch experimented with cycle routes, speed bumps, home zones, and car-free city centres - these paved the way for the Netherlands’ current integrated network of cycle paths.

Not all of it worked.

Not all of it worked.

When I visited Dutch officials in Delft, they told me how they built big protected cycle paths but people didn’t use them, because they didn’t have the network joining them all up.

It's a mistake often made in other countries, including the UK.

It's a mistake often made in other countries, including the UK.

Most countries did not have the foresight to build cycle paths and safe streets in the 70s. The best time to start would have been then - but the second best time to start is now.

And the good news? The Dutch have experimented and shown what works to make streets safer.

And the good news? The Dutch have experimented and shown what works to make streets safer.

53 years later, cars are safer, collisions are fewer. But so are the number of people walking and cycling. More children get driven in cars to keep them safe from other cars.

But we’re kidding ourselves if we think things are OK.

As the data shows.

But we’re kidding ourselves if we think things are OK.

As the data shows.

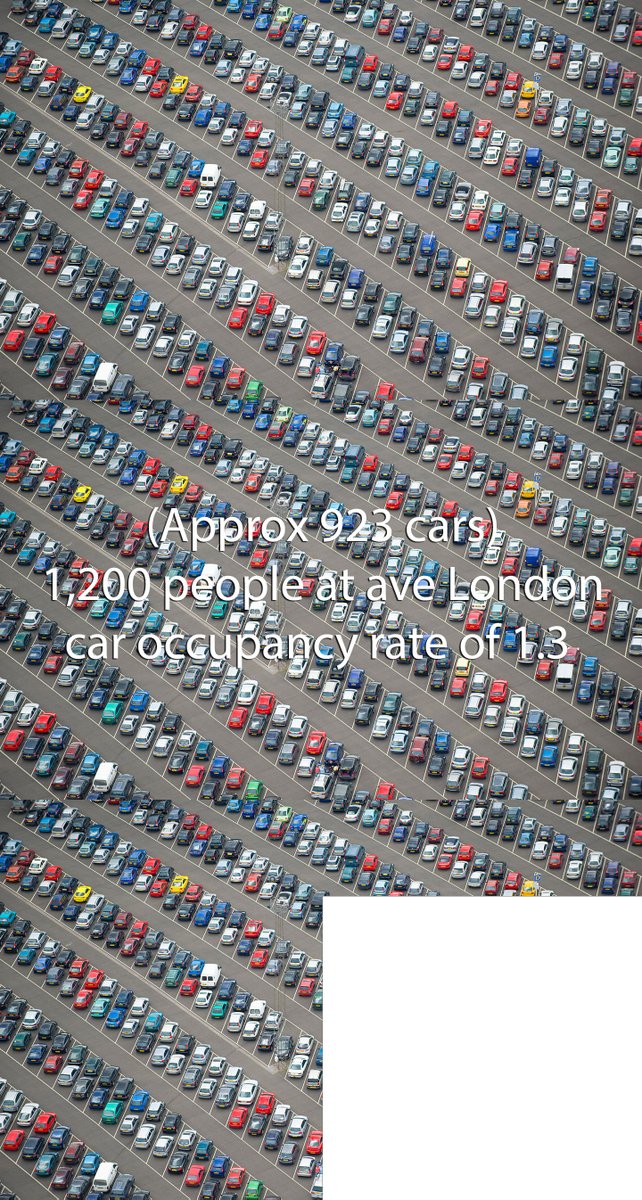

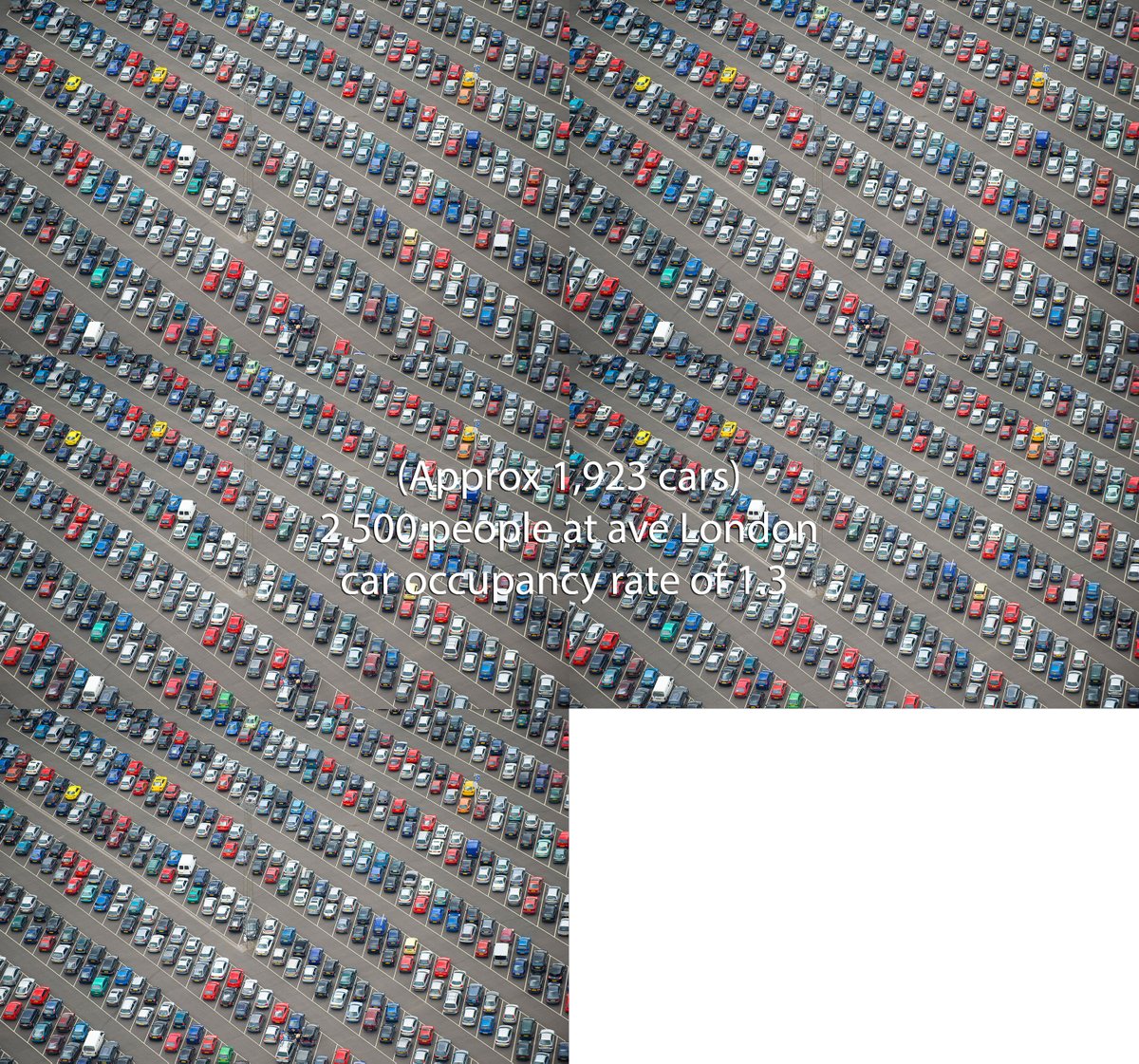

5,336 children aged 0-15 are killed or seriously injured (often life-changing issues) on our roads each year in England alone.

That’s over 14 children killed or seriously injured per day in England.

That’s over 14 children killed or seriously injured per day in England.

Some people reading this will think “But we’re not Amsterdam.”

But Amsterdam back then wasn’t like the Amsterdam we know now either.

But Amsterdam back then wasn’t like the Amsterdam we know now either.

We have the knowledge and tools to make our streets significantly better and safer for children. For all.

In most cases, more people feeling safe will even make things better for drivers - reducing congestion from short trips that would be better taken by other modes.

In most cases, more people feeling safe will even make things better for drivers - reducing congestion from short trips that would be better taken by other modes.

Simone Langenhoff never got to see the better future created in her name. Her father Vic would have rather avoided the anguish following his daughter’s death.

But thousands of families have been saved from the same loss and grief as a result of the campaigning that followed.

But thousands of families have been saved from the same loss and grief as a result of the campaigning that followed.

It’s never too late to take our streets back for children.

We know what to do. We know what it takes: political will and funding.

The new Labour government has even said "Taking back our streets" will be one of their 5 missions.

So, let’s do it...

We know what to do. We know what it takes: political will and funding.

The new Labour government has even said "Taking back our streets" will be one of their 5 missions.

So, let’s do it...

Sources:

1972 article (in Dutch): delpher.nl/nl/kranten/vie…

The Guardian interview with Maartje van Putten, former MEP: theguardian.com/cities/2015/ma…

Road collision data (children aged 0-15): lginform.local.gov.uk/reports/lgasta…

Delft Cycle Network: bicycledutch.wordpress.com/2019/02/27/the…

1972 article (in Dutch): delpher.nl/nl/kranten/vie…

The Guardian interview with Maartje van Putten, former MEP: theguardian.com/cities/2015/ma…

Road collision data (children aged 0-15): lginform.local.gov.uk/reports/lgasta…

Delft Cycle Network: bicycledutch.wordpress.com/2019/02/27/the…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh