1/ Soviet Nuclear Fission: Control of the Nuclear Arsenal in a Disintegrating Soviet Union

➡️A must-read, pivotal 1991 Harvard study by Obama’s future Secretary of Defence that led to the US pursuing its Russia-first nuclear strategy at the expense of Ukraine

I've highlighted some key points in this thread 🧵

Created by a team of Harvard analysts, and led by Ash Carter, Soviet Nuclear Fission defined America’s strategy in 1991 and was a huge contributor to the pressure Ukraine received from the Nunn-Lugar initiative to disarm.

It lays out the American hierarchy of goals in dealing with a collapsing Soviet Union and its nuclear arsenal.

Excerpts:

⚠️1⃣"...an increased risk of conventional conflict in Eurasia is... an acceptable price to pay for elimination of the major nuclear threat to the United States."

⚠️2⃣"…the United States should prefer that the Soviet nuclear complex remain firmly in Moscow’s hands…”

⚠️3⃣“…it involves the championing of Moscow’s preservation of nuclear superpower status.”

⚠️4⃣"...what is preferable for the United States may not be so attractive in Warsaw or Kiev."

✅5⃣“It could be in the U.S. interest to have Moscow worried about the nuclear threat from the Ukraine.”

⚠️6⃣“Threaten to withhold recognition and aid unless non-nuclear status is assured.”

⚠️7⃣“The United States could...discourage the inclusion of now-sovereign republics in international institutions such as the UN.”

✅8⃣“If the Ukraine exercises the nuclear option… would have a reasonable prospect of… establishing a fairly stable deterrent relationship with Moscow; it can be imagined as a potential medium nuclear power along the lines of Britain and France.”

✅9⃣“It is distinctly possible that the United States will need to cope with outcomes it does not prefer but cannot prevent… Successor state proliferation may occur.”

➡️A must-read, pivotal 1991 Harvard study by Obama’s future Secretary of Defence that led to the US pursuing its Russia-first nuclear strategy at the expense of Ukraine

I've highlighted some key points in this thread 🧵

Created by a team of Harvard analysts, and led by Ash Carter, Soviet Nuclear Fission defined America’s strategy in 1991 and was a huge contributor to the pressure Ukraine received from the Nunn-Lugar initiative to disarm.

It lays out the American hierarchy of goals in dealing with a collapsing Soviet Union and its nuclear arsenal.

Excerpts:

⚠️1⃣"...an increased risk of conventional conflict in Eurasia is... an acceptable price to pay for elimination of the major nuclear threat to the United States."

⚠️2⃣"…the United States should prefer that the Soviet nuclear complex remain firmly in Moscow’s hands…”

⚠️3⃣“…it involves the championing of Moscow’s preservation of nuclear superpower status.”

⚠️4⃣"...what is preferable for the United States may not be so attractive in Warsaw or Kiev."

✅5⃣“It could be in the U.S. interest to have Moscow worried about the nuclear threat from the Ukraine.”

⚠️6⃣“Threaten to withhold recognition and aid unless non-nuclear status is assured.”

⚠️7⃣“The United States could...discourage the inclusion of now-sovereign republics in international institutions such as the UN.”

✅8⃣“If the Ukraine exercises the nuclear option… would have a reasonable prospect of… establishing a fairly stable deterrent relationship with Moscow; it can be imagined as a potential medium nuclear power along the lines of Britain and France.”

✅9⃣“It is distinctly possible that the United States will need to cope with outcomes it does not prefer but cannot prevent… Successor state proliferation may occur.”

2/ Ash Carter

Ash Carter was the director of the Center for Science and International Affairs (CSIA) at Harvard University's John F. Kennedy School of Government, where he was also a professor.

He later became assistant secretary of defense for international security policy under President Bill Clinton where he was put in place to work on nuclear non-proliferation programs that removed nuclear weapons from Ukraine, Kazakhstan and Belarus.

He later became Obama’s Defense Secretary in 2015.

Ash Carter was the director of the Center for Science and International Affairs (CSIA) at Harvard University's John F. Kennedy School of Government, where he was also a professor.

He later became assistant secretary of defense for international security policy under President Bill Clinton where he was put in place to work on nuclear non-proliferation programs that removed nuclear weapons from Ukraine, Kazakhstan and Belarus.

He later became Obama’s Defense Secretary in 2015.

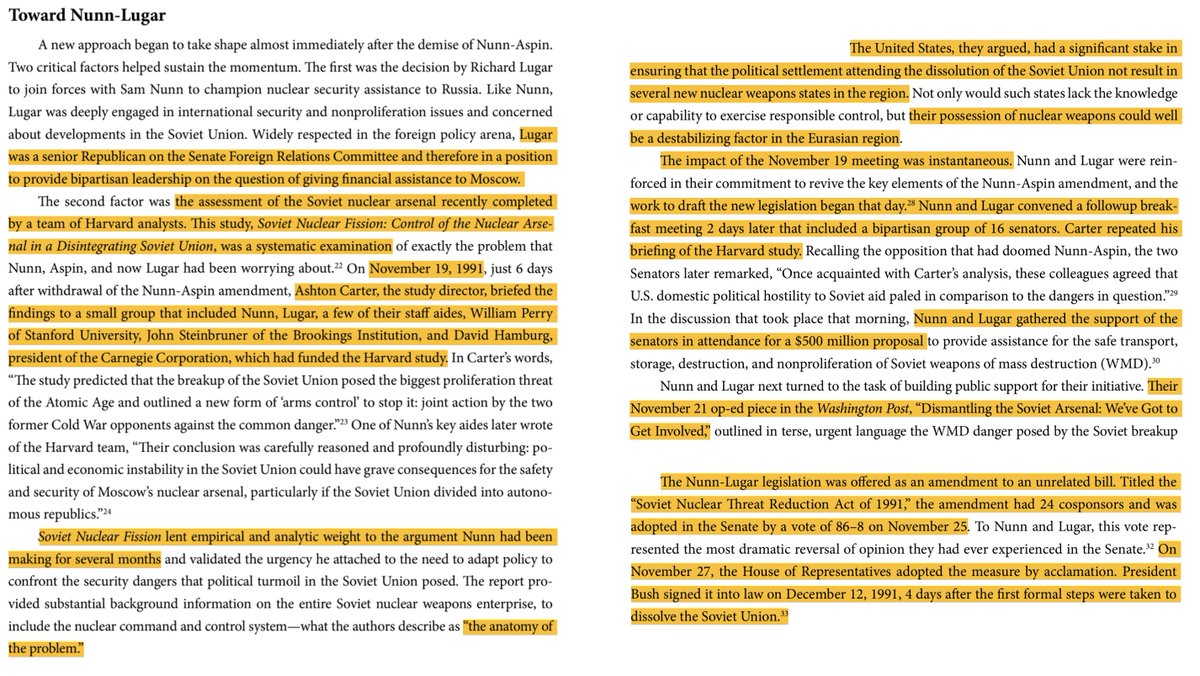

3/ Significant Impact of the study

On Nov 19, 1991, Ashton Carter briefed Richard Lugar, Sam Nunn, and William Perry (Clinton’s future Secretary of Defense) on the research done in this study.

This led to a gathering of 16 senators also getting briefed on the study, resulting in legislation being drafted, voted on in the Senate, and signed into law by George H.W. Bush.

The full text of the study is accessible through the Harvard viewer link here:

iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view…

Now let’s get into the content of the study. ⬇️

On Nov 19, 1991, Ashton Carter briefed Richard Lugar, Sam Nunn, and William Perry (Clinton’s future Secretary of Defense) on the research done in this study.

This led to a gathering of 16 senators also getting briefed on the study, resulting in legislation being drafted, voted on in the Senate, and signed into law by George H.W. Bush.

The full text of the study is accessible through the Harvard viewer link here:

iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view…

Now let’s get into the content of the study. ⬇️

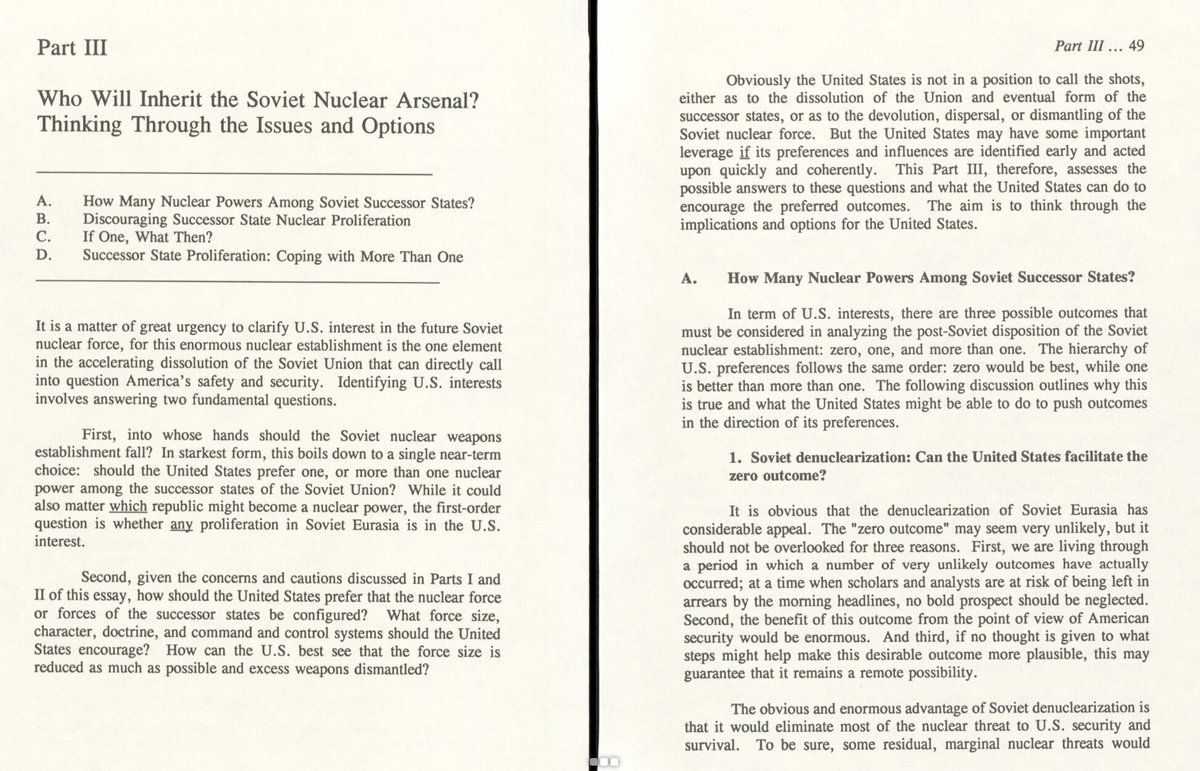

4/ Pages 48-49

"Part III: Who will inherit the Soviet Nuclear Arsenal? Thinking Through the Issues and Options

Identifying U.S. interests involves answering two fundamental questions… First, into whose hands should the Soviet nuclear weapons establishment fall? In starkest form, this boils down to a single near-term choice: Should the United States prefer one, or more than one nuclear power among the successor states of the Soviet Union? Second… How should the United States prefer that the nuclear force or forces of the successor states be configured?

In term of U.S. interests, there are three possible outcomes that must be considered for the post-Soviet disposition of the Soviet nuclear establishment: Zero, one, and more than one.

The hierarchy of the U.S. preferences follows the same order: Zero, one, more than one.”

"Part III: Who will inherit the Soviet Nuclear Arsenal? Thinking Through the Issues and Options

Identifying U.S. interests involves answering two fundamental questions… First, into whose hands should the Soviet nuclear weapons establishment fall? In starkest form, this boils down to a single near-term choice: Should the United States prefer one, or more than one nuclear power among the successor states of the Soviet Union? Second… How should the United States prefer that the nuclear force or forces of the successor states be configured?

In term of U.S. interests, there are three possible outcomes that must be considered for the post-Soviet disposition of the Soviet nuclear establishment: Zero, one, and more than one.

The hierarchy of the U.S. preferences follows the same order: Zero, one, more than one.”

5/ Pages 49-51

"Soviet Denuclearization: Can the United States facilitate the zero outcome?

A second source of concern is the potential geostrategic consequences of Soviet denuclearization. Insofar as nuclear weapons have played a substantial role in keeping the peace, Soviet denuclearization would increase the risk of war in the Eurasian heartland.

It is at least plausible, for example, that the Chinese, the Iranians, the Poles, or others, might be more aggressive at pressing their territorial or ethnic claims against a non-nuclear Moscow. Conflict in such settings would undoubtedly touch U.S. interests to at least some extent, since it seems likely that the United States (or even would want to) remain aloof from significant conflict in Eurasia.

But again, an increased risk of conventional conflict in Eurasia is, we think most would agree, an acceptable price to pay for elimination of the major nuclear threat to the United States."

"Soviet Denuclearization: Can the United States facilitate the zero outcome?

A second source of concern is the potential geostrategic consequences of Soviet denuclearization. Insofar as nuclear weapons have played a substantial role in keeping the peace, Soviet denuclearization would increase the risk of war in the Eurasian heartland.

It is at least plausible, for example, that the Chinese, the Iranians, the Poles, or others, might be more aggressive at pressing their territorial or ethnic claims against a non-nuclear Moscow. Conflict in such settings would undoubtedly touch U.S. interests to at least some extent, since it seems likely that the United States (or even would want to) remain aloof from significant conflict in Eurasia.

But again, an increased risk of conventional conflict in Eurasia is, we think most would agree, an acceptable price to pay for elimination of the major nuclear threat to the United States."

6/ Page 51

[Oleg: The "Zero Option" Is Reasoned to be Unlikely ⬇️]

"The inheritors of the Soviet nuclear complex, however, are unlikely to find denuclearization to be in their interest for one clearcut reason. They will themselves face a number of actual or potential nuclear threats and will therefore have very strong incentives to retain at least some nuclear deterrent capability.

Even if Moscow were sufficiently confident of the enduring benevolence of the Western industrial nuclear powers to contemplate denuclearization, it would still face along its border both nuclear-capable states such as China and India and potential proliferators such as North Korea, Pakistan, Iran, and Iraq. Furthermore, pessimists among Moscow’s security policymakers might worry about the long-term threat of proliferation in such states as Germany and Poland.

There are, in short, strong reasons for thinking that at least one Soviet successor state will believe that its security requires the possession of nuclear weapons.

Obviously given the magnitude for Moscow of a decision to denuclearize, more than minor concessions would be required for U.S. policy to have any substantial effect on Moscow’s decision making.

One possibility is that it could offer up its [America's] own nuclear forces. This would provide the deep appeal of a symmetrical outcome in terms of Soviet and American forces. But this would solve only part of the nuclear threat to Moscow and, moreover, the United States would have the same powerful incentives as Moscow to retain a nuclear capability. Hence, this approach does not seem especially promising."

[Oleg: The "Zero Option" Is Reasoned to be Unlikely ⬇️]

"The inheritors of the Soviet nuclear complex, however, are unlikely to find denuclearization to be in their interest for one clearcut reason. They will themselves face a number of actual or potential nuclear threats and will therefore have very strong incentives to retain at least some nuclear deterrent capability.

Even if Moscow were sufficiently confident of the enduring benevolence of the Western industrial nuclear powers to contemplate denuclearization, it would still face along its border both nuclear-capable states such as China and India and potential proliferators such as North Korea, Pakistan, Iran, and Iraq. Furthermore, pessimists among Moscow’s security policymakers might worry about the long-term threat of proliferation in such states as Germany and Poland.

There are, in short, strong reasons for thinking that at least one Soviet successor state will believe that its security requires the possession of nuclear weapons.

Obviously given the magnitude for Moscow of a decision to denuclearize, more than minor concessions would be required for U.S. policy to have any substantial effect on Moscow’s decision making.

One possibility is that it could offer up its [America's] own nuclear forces. This would provide the deep appeal of a symmetrical outcome in terms of Soviet and American forces. But this would solve only part of the nuclear threat to Moscow and, moreover, the United States would have the same powerful incentives as Moscow to retain a nuclear capability. Hence, this approach does not seem especially promising."

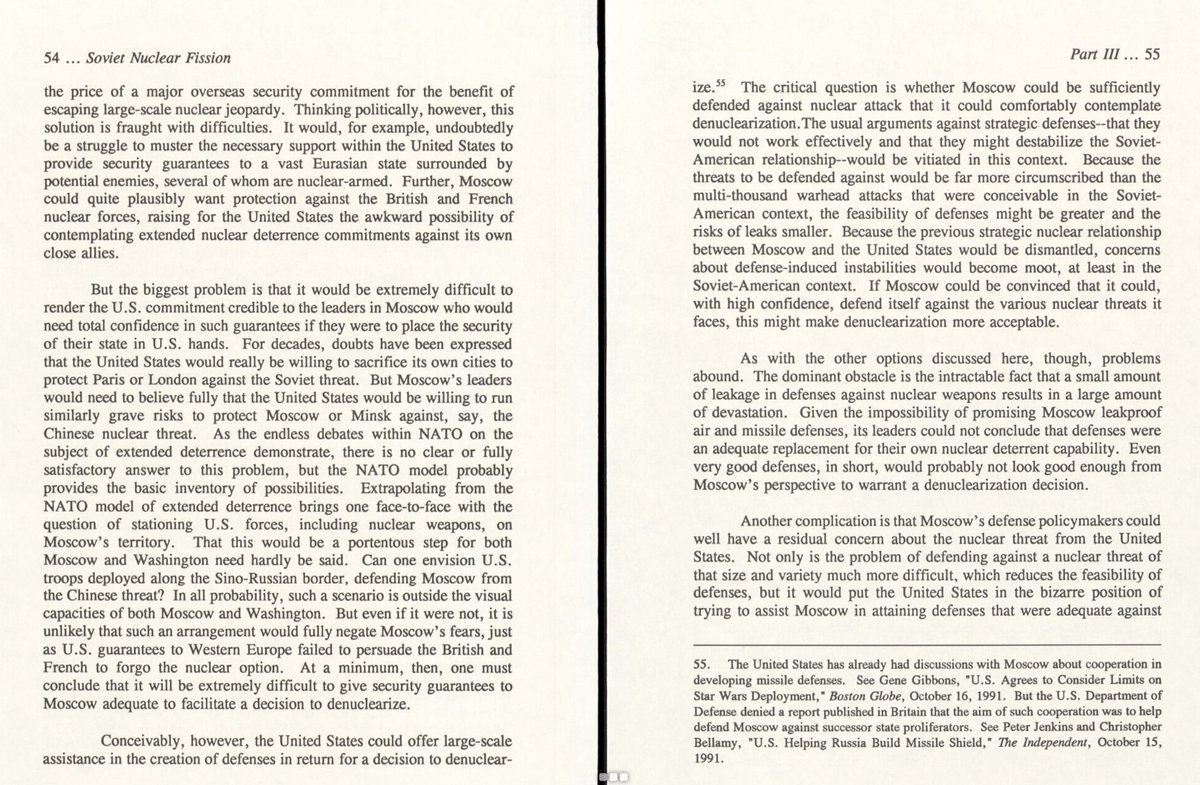

7/ Page 54

"It would… undoubtedly be a struggle to muster the necessary support within the United States to provide security guarantees to a vast Eurasian state surrounded by potential enemies, several of whom are nuclear-armed. Further, Moscow could quite plausibly want protection against the British and French nuclear forces, raising for the United States the awkward possibility of contemplating extended nuclear deterrence commitments against its own close allies."

But the biggest problem is that it would be extremely difficult to render the U.S. commitment credible to the leaders in Moscow who would need total confidence in such guarantees if they were to place the security of their state in U.S. hands. For decades, doubts have been expressed that the United States would really be willing to sacrifice its own cities to protect Paris or London against the Soviet threat. But Moscow’s leaders would need to believe fully that the United States would be willing to run similarly grave risks to protect Moscow or Minsk against, say, the Chinese nuclear threat… Can one envision U.S. troops deployed along the Sino-Russian border, defending Moscow from the Chinese threat? In all probability, such a scenario is outside the visual capacities of both Moscow and Washington. But even if it were not, it is unlikely that such an arrangement would fully negate Moscow’s fears, just as U.S. guarantees to Western Europe failed to persuade the British and French to forgo the nuclear option.

At a minimum, then, one must conclude that it will be extremely difficult to give security guarantees to Moscow adequate to facilitate a decision to denuclearize."

[Oleg: The Harvard team continues on to consider the other two options - one or many ⬇️]

"It would… undoubtedly be a struggle to muster the necessary support within the United States to provide security guarantees to a vast Eurasian state surrounded by potential enemies, several of whom are nuclear-armed. Further, Moscow could quite plausibly want protection against the British and French nuclear forces, raising for the United States the awkward possibility of contemplating extended nuclear deterrence commitments against its own close allies."

But the biggest problem is that it would be extremely difficult to render the U.S. commitment credible to the leaders in Moscow who would need total confidence in such guarantees if they were to place the security of their state in U.S. hands. For decades, doubts have been expressed that the United States would really be willing to sacrifice its own cities to protect Paris or London against the Soviet threat. But Moscow’s leaders would need to believe fully that the United States would be willing to run similarly grave risks to protect Moscow or Minsk against, say, the Chinese nuclear threat… Can one envision U.S. troops deployed along the Sino-Russian border, defending Moscow from the Chinese threat? In all probability, such a scenario is outside the visual capacities of both Moscow and Washington. But even if it were not, it is unlikely that such an arrangement would fully negate Moscow’s fears, just as U.S. guarantees to Western Europe failed to persuade the British and French to forgo the nuclear option.

At a minimum, then, one must conclude that it will be extremely difficult to give security guarantees to Moscow adequate to facilitate a decision to denuclearize."

[Oleg: The Harvard team continues on to consider the other two options - one or many ⬇️]

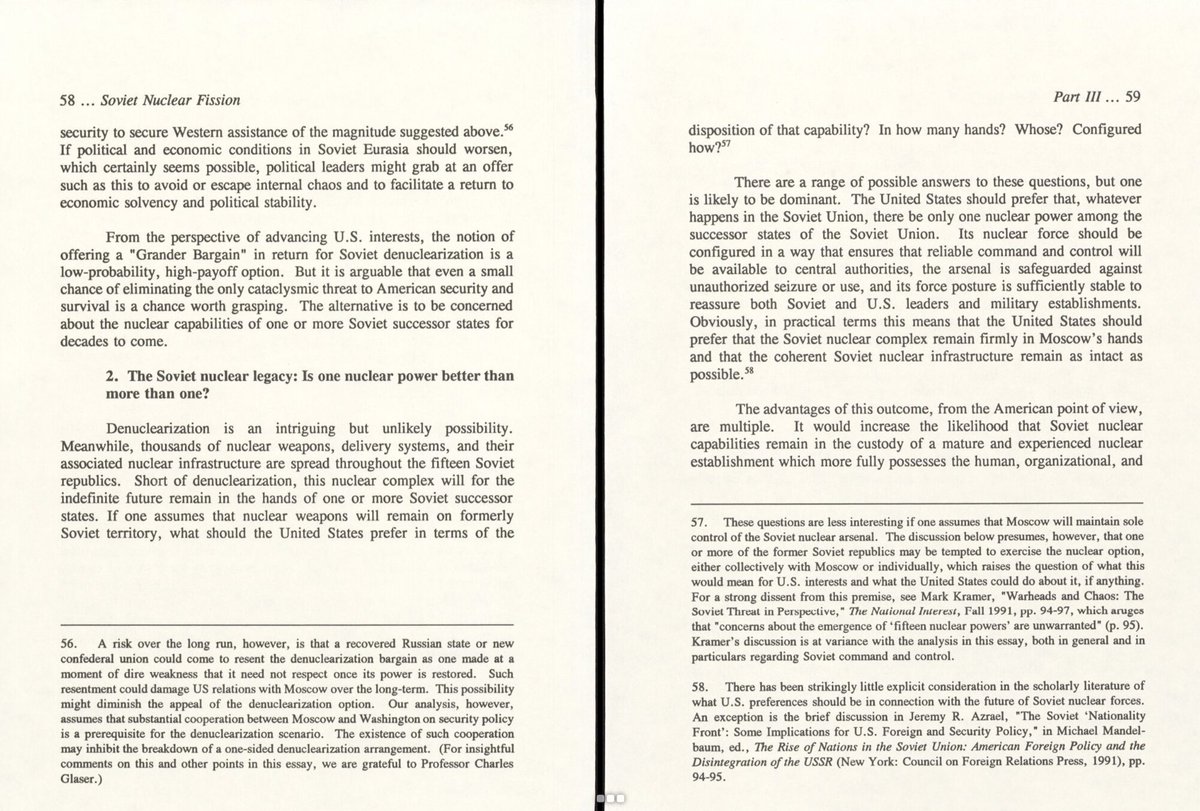

8/ Pages 58-61

"The Soviet nuclear legacy: Is one nuclear power better than more than one?

If one assumes that nuclear weapons will remain on formerly Soviet territory, what should the United States prefer in terms of the disposition of that capability? In how many hands? Configured how?

There are a range of possible answers to these questions, but one is likely to be dominant. The United States should prefer that, whatever happens in the Soviet Union, there be only one nuclear power among the successor states of the Soviet Union. Obviously, in practical terms, this means that the United States should prefer that the Soviet nuclear complex remain firmly in Moscow’s hands and that the coherent Soviet nuclear infrastructure remain as intact as possible.

In contrast, proliferation in successor states would put nuclear weapons in the hands of inexperienced and possibly unstable governments, which are likely to be populated by people new to the problem of security policy. Moreover, it is plausible to expect conflict within and between some of the Soviet successor states, in which nuclear weapons might become a target for grabbing in some civil conflict or become an issue or, worse, an instrument, in interstate conflict. In short, most of the reasons that the United States regards it as in its best interest to oppose nuclear proliferation apply, perhaps with special intensity, to the case of Soviet successor states. This is a strong reason for preferring that a single nuclear state arise out of the disintegration of the Soviet Union.

[Oleg: Note, this concern regarding internal conflict has now been eliminated in Ukraine ⬆️]

In addition, the emergence from Soviet Eurasia of a single nuclear power is likely to be by far the best outcome in terms of expediting future nuclear arms control efforts. Successor state proliferation would be at least a major complication for, and perhaps a fatal blow to, the nuclear arms control process. It would impose far more complicated security calculations on Moscow and the nuclear successor states, would probably far more tangled multilateral negotiations, and would create a situation in which it would probably be exceedingly difficult to determine, much less successfully negotiate, equitable arms control outcomes.

The preference for a single nuclear state is not without costs and difficulties, however. For one thing, it involves the championing of Moscow’s preservation of nuclear superpower status. This may not be universally popular in domestic terms in the United States."

"The Soviet nuclear legacy: Is one nuclear power better than more than one?

If one assumes that nuclear weapons will remain on formerly Soviet territory, what should the United States prefer in terms of the disposition of that capability? In how many hands? Configured how?

There are a range of possible answers to these questions, but one is likely to be dominant. The United States should prefer that, whatever happens in the Soviet Union, there be only one nuclear power among the successor states of the Soviet Union. Obviously, in practical terms, this means that the United States should prefer that the Soviet nuclear complex remain firmly in Moscow’s hands and that the coherent Soviet nuclear infrastructure remain as intact as possible.

In contrast, proliferation in successor states would put nuclear weapons in the hands of inexperienced and possibly unstable governments, which are likely to be populated by people new to the problem of security policy. Moreover, it is plausible to expect conflict within and between some of the Soviet successor states, in which nuclear weapons might become a target for grabbing in some civil conflict or become an issue or, worse, an instrument, in interstate conflict. In short, most of the reasons that the United States regards it as in its best interest to oppose nuclear proliferation apply, perhaps with special intensity, to the case of Soviet successor states. This is a strong reason for preferring that a single nuclear state arise out of the disintegration of the Soviet Union.

[Oleg: Note, this concern regarding internal conflict has now been eliminated in Ukraine ⬆️]

In addition, the emergence from Soviet Eurasia of a single nuclear power is likely to be by far the best outcome in terms of expediting future nuclear arms control efforts. Successor state proliferation would be at least a major complication for, and perhaps a fatal blow to, the nuclear arms control process. It would impose far more complicated security calculations on Moscow and the nuclear successor states, would probably far more tangled multilateral negotiations, and would create a situation in which it would probably be exceedingly difficult to determine, much less successfully negotiate, equitable arms control outcomes.

The preference for a single nuclear state is not without costs and difficulties, however. For one thing, it involves the championing of Moscow’s preservation of nuclear superpower status. This may not be universally popular in domestic terms in the United States."

9/ Page 62

"It also has profound geostrategic consequences for Soviet Eurasia and adjacent areas. In effect, it has to do with what sort of security order emerges in the East. And what is preferable for the United States may not be so attractive in Warsaw or Kiev.

This leads directly to a second point, which is that the U.S. preference for a single nuclear power would deeply influence U.S. relations with successor states, in one of two contrary ways. On the one hand, it would put the United States at cross purposes with successor states that had an interest in acquiring a nuclear capability. Understandably, states that have concluded that nuclear weapons are necessary for their security may not be swayed from this path because it is inconvenient for the United States, nor are they likely to be pleased by U.S. efforts to pressure them onto a different path or prevent them from attaining nuclear capability.

On the other hand, it is conceivable that the United States could end up in the business of providing, or would be pressed to provide, security guarantees to Soviet successor states as an inducement to forego the nuclear option.

[Oleg: This is likely the seed that led to the Budapest Memorandum and Polish NATO entry ⬆️]

It would also put the United States in the somewhat awkward position of championing Moscow’s nuclear status while offering protection to those who might be threatened by it."

"It also has profound geostrategic consequences for Soviet Eurasia and adjacent areas. In effect, it has to do with what sort of security order emerges in the East. And what is preferable for the United States may not be so attractive in Warsaw or Kiev.

This leads directly to a second point, which is that the U.S. preference for a single nuclear power would deeply influence U.S. relations with successor states, in one of two contrary ways. On the one hand, it would put the United States at cross purposes with successor states that had an interest in acquiring a nuclear capability. Understandably, states that have concluded that nuclear weapons are necessary for their security may not be swayed from this path because it is inconvenient for the United States, nor are they likely to be pleased by U.S. efforts to pressure them onto a different path or prevent them from attaining nuclear capability.

On the other hand, it is conceivable that the United States could end up in the business of providing, or would be pressed to provide, security guarantees to Soviet successor states as an inducement to forego the nuclear option.

[Oleg: This is likely the seed that led to the Budapest Memorandum and Polish NATO entry ⬆️]

It would also put the United States in the somewhat awkward position of championing Moscow’s nuclear status while offering protection to those who might be threatened by it."

10/ Pages 62-63

[Oleg: critical to today's situation ⬇️]

"There are, in addition, some counter-arguments that should not be completely ignored. Several arguments could be made in support of the proposition that U.S. interests could be furthered, or at least not harmed, by nuclear proliferation among the Soviet successor states… But if one believed that proliferation would be stabilizing if safely handled, this could shift the focus of policy from preventing to managing the spread of nuclear capabilities.

Second, it could be argued that insofar as nuclear proliferation occurs among the Soviet successor states, the resulting nuclear capabilities are likely to be mostly directed at one another. Nuclear successor states are unlikely to have any reason to threaten the United States with nuclear weapons, but plenty of motivation to threaten Moscow. It could be in the U.S. interest to have Moscow worried about the nuclear threat from the Ukraine, for example, or Kazakhstan. It might be desirable if Moscow had to divert some of its nuclear attention away from the United States. This could, arguably, weaken Moscow in relative terms and thereby enhance America’s geostrategic interests in Eurasia.

A third argument is suggested by the second: argument basic tenet of U.S. grand strategy has been the importance of protecting industrial Eurasia against the threat from Moscow. At least with reference to Western Europe, proliferation to states such as the Ukraine or Byelorussia could produce a nuclear-equipped buffer zone that would stand between Moscow and America’s industrial allies in the west."

[Oleg: This could be replaced with a Polish & Ukrainian nuclear buffer zone ⬆️]

[Oleg: critical to today's situation ⬇️]

"There are, in addition, some counter-arguments that should not be completely ignored. Several arguments could be made in support of the proposition that U.S. interests could be furthered, or at least not harmed, by nuclear proliferation among the Soviet successor states… But if one believed that proliferation would be stabilizing if safely handled, this could shift the focus of policy from preventing to managing the spread of nuclear capabilities.

Second, it could be argued that insofar as nuclear proliferation occurs among the Soviet successor states, the resulting nuclear capabilities are likely to be mostly directed at one another. Nuclear successor states are unlikely to have any reason to threaten the United States with nuclear weapons, but plenty of motivation to threaten Moscow. It could be in the U.S. interest to have Moscow worried about the nuclear threat from the Ukraine, for example, or Kazakhstan. It might be desirable if Moscow had to divert some of its nuclear attention away from the United States. This could, arguably, weaken Moscow in relative terms and thereby enhance America’s geostrategic interests in Eurasia.

A third argument is suggested by the second: argument basic tenet of U.S. grand strategy has been the importance of protecting industrial Eurasia against the threat from Moscow. At least with reference to Western Europe, proliferation to states such as the Ukraine or Byelorussia could produce a nuclear-equipped buffer zone that would stand between Moscow and America’s industrial allies in the west."

[Oleg: This could be replaced with a Polish & Ukrainian nuclear buffer zone ⬆️]

11/ Page 64

[Oleg: 📕This goes into some details about the downsides, conflict spilling into Western Europe, weapons transfers to the Middle East and harm to nonproliferation elsewhere]

"All things considered, then, and in the absence of Soviet denuclearization, the U.S. interest seems to be in the retention of a single nuclear power in Soviet Eurasia… What can the United States do to help achieve this outcome?"

Pages 65-67

"Discouraging Successor State Proliferation

…the operational concern will be to devise a scheme acceptable to the newly independent republics for the safe and secure removal of the nuclear weapons on their territory.

Unfortunately, all of the non-Russian republics of the former Soviet Union will, if they choose to become fully independent, suffer the uneasy fate of living with a giant neighbor whose potential power is tremendous and whose historical propensity to devour its neighbors is proven definitely by their own unpleasant history of subjugation to Moscow.

One or more successor states could regard its long-term security problems as intractable in the absence of a nuclear deterrent capability. They could easily feel, as the states of Europe have felt, weak, vulnerable, and isolated, and conclude that only nuclear weapons can provide a level of security compatible with the full enjoyment of sovereignty.

A second motivation, less primal than security but nevertheless potentially real, is the desire for the status that accompanies being a nuclear state. The nuclear club is a select group. In a variety of international settings, including the NPT regime, the nuclear weapons states are accorded special standing and have different rights and responsibilities from other states. Nuclear status guarantees that a state is a major player, at least in a regional context and also possibly in some global contexts.

It is plausible that the Ukraine, for example, would prefer that the nuclear status of Soviet Eurasia not be determined in bilateral discussions between Moscow and Washington.

…Soviet successor states may want to get their hands on nuclear weapons, at least for a while, because of the diplomatic leverage they may provide… They could have large value in two very important relationships: those with Moscow and those wit the United States…"

[Oleg: 📕This goes into some details about the downsides, conflict spilling into Western Europe, weapons transfers to the Middle East and harm to nonproliferation elsewhere]

"All things considered, then, and in the absence of Soviet denuclearization, the U.S. interest seems to be in the retention of a single nuclear power in Soviet Eurasia… What can the United States do to help achieve this outcome?"

Pages 65-67

"Discouraging Successor State Proliferation

…the operational concern will be to devise a scheme acceptable to the newly independent republics for the safe and secure removal of the nuclear weapons on their territory.

Unfortunately, all of the non-Russian republics of the former Soviet Union will, if they choose to become fully independent, suffer the uneasy fate of living with a giant neighbor whose potential power is tremendous and whose historical propensity to devour its neighbors is proven definitely by their own unpleasant history of subjugation to Moscow.

One or more successor states could regard its long-term security problems as intractable in the absence of a nuclear deterrent capability. They could easily feel, as the states of Europe have felt, weak, vulnerable, and isolated, and conclude that only nuclear weapons can provide a level of security compatible with the full enjoyment of sovereignty.

A second motivation, less primal than security but nevertheless potentially real, is the desire for the status that accompanies being a nuclear state. The nuclear club is a select group. In a variety of international settings, including the NPT regime, the nuclear weapons states are accorded special standing and have different rights and responsibilities from other states. Nuclear status guarantees that a state is a major player, at least in a regional context and also possibly in some global contexts.

It is plausible that the Ukraine, for example, would prefer that the nuclear status of Soviet Eurasia not be determined in bilateral discussions between Moscow and Washington.

…Soviet successor states may want to get their hands on nuclear weapons, at least for a while, because of the diplomatic leverage they may provide… They could have large value in two very important relationships: those with Moscow and those wit the United States…"

12/ Page 68-69

"What can the United States do? There are a number of ideas worth considering:

1. Minimize Soviet disintegration

One solution to the successor state proliferation problem would be to have no successor states. In terms of American policy, this would mean supporting the emergence of a single unitary state from the former Soviet Union… one could argue that, proliferation worries aside, the U.S. interest is in maximum disintegration of the Soviet Union, since this would shrink the power base controlled by Moscow while surrounding it with states that would have a strong incentive to balance against it. If nuclear weapons did not exist, there would seem to be a strong case for supporting the full fracturing of the Soviet Union. As we have seen, nuclear weapons change this calculation dramatically.

...In fact, U.S. policy over the past several years has tilted strongly towards Moscow and against disintegration. There has been a clear preference for dealing with central authorities in Moscow and a clear reluctance to deal with, legitimize, or recognize the republics as sovereign entities. However, since a number of republics have either already attained or have declared themselves to be on the road to full independence, this outcome now seems impossible."

"What can the United States do? There are a number of ideas worth considering:

1. Minimize Soviet disintegration

One solution to the successor state proliferation problem would be to have no successor states. In terms of American policy, this would mean supporting the emergence of a single unitary state from the former Soviet Union… one could argue that, proliferation worries aside, the U.S. interest is in maximum disintegration of the Soviet Union, since this would shrink the power base controlled by Moscow while surrounding it with states that would have a strong incentive to balance against it. If nuclear weapons did not exist, there would seem to be a strong case for supporting the full fracturing of the Soviet Union. As we have seen, nuclear weapons change this calculation dramatically.

...In fact, U.S. policy over the past several years has tilted strongly towards Moscow and against disintegration. There has been a clear preference for dealing with central authorities in Moscow and a clear reluctance to deal with, legitimize, or recognize the republics as sovereign entities. However, since a number of republics have either already attained or have declared themselves to be on the road to full independence, this outcome now seems impossible."

13/ Page 70-73

"…the United States may have little leverage on the disintegration question. But it can try to create incentives for union rather than independence. This could be attempted, for example, by making it clear that U.S. economic assistance will be negotiated with and funneled only through Moscow. Similarly, the United States could make it clear that it will not discuss security matters separately with the republics, but only with central authorities in Moscow… these measures could be counterproductive, antagonizing the very states the United States will need to influence if it is to have any effect on nuclear proliferation decisions of newly independent republics.

2. Encourage withdrawal of nuclear weapons from the republics

A second approach would be to encourage Moscow to pull all its nuclear capabilities back into territory that it would surely control, whatever the extent of Soviet disintegration… An attempt by Moscow to remove these nuclear capabilities could also provoke conflict… Without a doubt, this is a scenario best avoided.

3. Utilize START or the NPT to remove nuclear weapons from the republics

A third option, which could be regarded as a variant of the “weapons pullback” idea, would be to exploit existing agreements that are or might be applicable to the weapons deployed in the republics. For example, the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START) could be used as a mechanism to arrange for removal of strategic nuclear forces from the Byelorussia, the Ukraine, and Kazakhstan… So all of the strategic weapons deployed outside of Russia could be eliminated by implementing the START agreement. Indeed, this appears compatible with the declared policy of the Ukraine, at least.

For this to be a meaningful option to address near-term proliferation concerns, several requirements have to be met. First, the treaty must be promptly ratified, otherwise it has no legal force."

"…the United States may have little leverage on the disintegration question. But it can try to create incentives for union rather than independence. This could be attempted, for example, by making it clear that U.S. economic assistance will be negotiated with and funneled only through Moscow. Similarly, the United States could make it clear that it will not discuss security matters separately with the republics, but only with central authorities in Moscow… these measures could be counterproductive, antagonizing the very states the United States will need to influence if it is to have any effect on nuclear proliferation decisions of newly independent republics.

2. Encourage withdrawal of nuclear weapons from the republics

A second approach would be to encourage Moscow to pull all its nuclear capabilities back into territory that it would surely control, whatever the extent of Soviet disintegration… An attempt by Moscow to remove these nuclear capabilities could also provoke conflict… Without a doubt, this is a scenario best avoided.

3. Utilize START or the NPT to remove nuclear weapons from the republics

A third option, which could be regarded as a variant of the “weapons pullback” idea, would be to exploit existing agreements that are or might be applicable to the weapons deployed in the republics. For example, the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START) could be used as a mechanism to arrange for removal of strategic nuclear forces from the Byelorussia, the Ukraine, and Kazakhstan… So all of the strategic weapons deployed outside of Russia could be eliminated by implementing the START agreement. Indeed, this appears compatible with the declared policy of the Ukraine, at least.

For this to be a meaningful option to address near-term proliferation concerns, several requirements have to be met. First, the treaty must be promptly ratified, otherwise it has no legal force."

14/ Pages 74-78

"The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) is another existing agreement that may have applicability and utility in addressing the nuclear weapons issue in the former Soviet Union. Moscow has a clear legal obligation under Article I of the NPT, whereby the nuclear weapons states “undertake not to transfer to any recipient whatsoever nuclear weapons… or control over such weapons…”

So long as Moscow claims to be, and is regarded by the international community as, the sole legitimate guardian of the full Soviet arsenal, Article I would clearly apply to the relationship between Moscow and independent successor states and would prohibit any transfer of nuclear weapons or associated technologies from Moscow to the republics.

5. Threaten to withhold recognition and aid unless non-nuclear status is assured

A fifth policy option would be to make more important elements of U.S. relations with successor states conditional on their non-nuclear status. This could take the form of an insistence that they sign the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and accept the associated international inspection regime if they wish to have normal or friendly relations with the United States.

The United States could withhold diplomatic recognition until the NPT had been signed.

Economic assistance and normal economic intercourse (including access to U.S. markets and capital) would be deemed to be out of the question until clear and tangible evidence of non-nuclear status had been given.

The United States could, on the same conditions, also resist or discourage the inclusion of now-sovereign republics in international institutions such as the UN…"

"The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) is another existing agreement that may have applicability and utility in addressing the nuclear weapons issue in the former Soviet Union. Moscow has a clear legal obligation under Article I of the NPT, whereby the nuclear weapons states “undertake not to transfer to any recipient whatsoever nuclear weapons… or control over such weapons…”

So long as Moscow claims to be, and is regarded by the international community as, the sole legitimate guardian of the full Soviet arsenal, Article I would clearly apply to the relationship between Moscow and independent successor states and would prohibit any transfer of nuclear weapons or associated technologies from Moscow to the republics.

5. Threaten to withhold recognition and aid unless non-nuclear status is assured

A fifth policy option would be to make more important elements of U.S. relations with successor states conditional on their non-nuclear status. This could take the form of an insistence that they sign the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and accept the associated international inspection regime if they wish to have normal or friendly relations with the United States.

The United States could withhold diplomatic recognition until the NPT had been signed.

Economic assistance and normal economic intercourse (including access to U.S. markets and capital) would be deemed to be out of the question until clear and tangible evidence of non-nuclear status had been given.

The United States could, on the same conditions, also resist or discourage the inclusion of now-sovereign republics in international institutions such as the UN…"

15/ Page 80-85

"It must be assumed that successor state proliferators will be deeply alienated by this treatment. They may feel, with reason, that sovereign states have the right to, and even the responsibility, to make adequate provisions for their national security and they ought not be punished if, in their judgement, their security requires nuclear weapons.

They may resent the double standard inherent in the imposition of anti-proliferation sanctions by outsiders who have themselves heavily relied on nuclear weapons for their own security.

None among Britain, France, China, Israel or India has suffered full or lasting opprobrium as a consequence of its nuclear status. Why should soviet successor states feel that they will end up any different? They may feel that a few years of international discomfort are a price worth paying in order to join the nuclear club.

There are, finally, the potentially adverse consequences of creating international outcasts. In a condition of “pariahtude,” states have little to lose in flouting international standards of behavior, little reason to cooperate in creating or maintaining international regimes or norms, and considerable motivation to behave in reckless or dangerous ways.

7. Offer security guarantees

Perhaps such states would be willing to trade the nuclear option for security guarantees from the United States or NATO… The question is then whether the United States, either singly or in league with its allies, would be willing to grant such guarantees…

This would tend to harm relations with Moscow, but even more worrying, it would mean that, in the event of conflict (far from unlikely in this part of the world), the United States would be caught in the middle. This might be a risk with running in return for denuclearization, but is it worth running only to contain the proliferation problem? Perhaps not, if other options might be sufficient."

"It must be assumed that successor state proliferators will be deeply alienated by this treatment. They may feel, with reason, that sovereign states have the right to, and even the responsibility, to make adequate provisions for their national security and they ought not be punished if, in their judgement, their security requires nuclear weapons.

They may resent the double standard inherent in the imposition of anti-proliferation sanctions by outsiders who have themselves heavily relied on nuclear weapons for their own security.

None among Britain, France, China, Israel or India has suffered full or lasting opprobrium as a consequence of its nuclear status. Why should soviet successor states feel that they will end up any different? They may feel that a few years of international discomfort are a price worth paying in order to join the nuclear club.

There are, finally, the potentially adverse consequences of creating international outcasts. In a condition of “pariahtude,” states have little to lose in flouting international standards of behavior, little reason to cooperate in creating or maintaining international regimes or norms, and considerable motivation to behave in reckless or dangerous ways.

7. Offer security guarantees

Perhaps such states would be willing to trade the nuclear option for security guarantees from the United States or NATO… The question is then whether the United States, either singly or in league with its allies, would be willing to grant such guarantees…

This would tend to harm relations with Moscow, but even more worrying, it would mean that, in the event of conflict (far from unlikely in this part of the world), the United States would be caught in the middle. This might be a risk with running in return for denuclearization, but is it worth running only to contain the proliferation problem? Perhaps not, if other options might be sufficient."

16/ Pages 107-109

"Successor State Proliferation: Coping with More Than One

Whatever U.S. preferences and policies, it is possible that there will be more than one Soviet successor state that chooses to become a nuclear power.

If this [denuclearization] is impossible to attain, the next best result is nuclear forces in Soviet Eurasia that lack intercontinental capability… But the “more-than-one” scenario involves implications and complexities that are not captured simply by replicating the Moscow-only analysis across the cases of proliferation.

Who and how many?

It also matters who the proliferators are. Several factors would affect U.S. response to various successor state proliferators. One criterion would be the prospect of meeting standards of responsible custodianship.

If the Ukraine exercises the nuclear option, for example, this would be proliferation to a state that, by virtue of its size and potential wealth, would have a reasonable prospect of developing a coherent nuclear establishment, acquiring a survivable nuclear capability, and establishing a fairly stable deterrent relationship with Moscow; it can be imagined as a potential medium nuclear power along the lines of Britain and France.

A second criterion would be the internal stability of the proliferating successor state or states. One basic element would be the presence or absence of domestic disorder.

A third criterion would be the proliferating state's relations with its neighbors. Successor state proliferation will be less distressing if it occurs in more peaceful and stable regional settings. There is, unfortunately, considerable potential for Soviet successor states to have bitter and conflictual relations with both Moscow and each other.

For American policymakers, a more parochial concern will be whether the state is friendly or hostile to the United States and its interests."

"Successor State Proliferation: Coping with More Than One

Whatever U.S. preferences and policies, it is possible that there will be more than one Soviet successor state that chooses to become a nuclear power.

If this [denuclearization] is impossible to attain, the next best result is nuclear forces in Soviet Eurasia that lack intercontinental capability… But the “more-than-one” scenario involves implications and complexities that are not captured simply by replicating the Moscow-only analysis across the cases of proliferation.

Who and how many?

It also matters who the proliferators are. Several factors would affect U.S. response to various successor state proliferators. One criterion would be the prospect of meeting standards of responsible custodianship.

If the Ukraine exercises the nuclear option, for example, this would be proliferation to a state that, by virtue of its size and potential wealth, would have a reasonable prospect of developing a coherent nuclear establishment, acquiring a survivable nuclear capability, and establishing a fairly stable deterrent relationship with Moscow; it can be imagined as a potential medium nuclear power along the lines of Britain and France.

A second criterion would be the internal stability of the proliferating successor state or states. One basic element would be the presence or absence of domestic disorder.

A third criterion would be the proliferating state's relations with its neighbors. Successor state proliferation will be less distressing if it occurs in more peaceful and stable regional settings. There is, unfortunately, considerable potential for Soviet successor states to have bitter and conflictual relations with both Moscow and each other.

For American policymakers, a more parochial concern will be whether the state is friendly or hostile to the United States and its interests."

17/ Page 113 - 116

“5. US interests and options

If multiple successor state nuclear proliferation occurs, what are U.S. interests and how might they be furthered?

a. Minimizing intercontinental capability

The paramount concern of the United States should be to minimize the direct threat to its own security…

The United States could also consider the threat of sanctions, along the lines discussed above in the context of discouraging successor state proliferation. At a minimum, it can safely be said that intercontinental capability will be a bone of contention in U.S. relations with the successor states.

e. Contain the nuclear contagion.

Nuclear successor states should be encouraged to behave responsibly with respect to more general non-proliferation regime. Even if they themselves have contravened the regime, it is not desirable to have them “off the reservation” contributing to still further proliferation…

...the United States and the international community should insist that nuclear successor states confirm to NPT norms of behavior for nuclear weapons states. They might even be invited to join the NPT regime as nuclear weapons states, although this too might create the appearance of accepting and rewarding proliferation.”

“5. US interests and options

If multiple successor state nuclear proliferation occurs, what are U.S. interests and how might they be furthered?

a. Minimizing intercontinental capability

The paramount concern of the United States should be to minimize the direct threat to its own security…

The United States could also consider the threat of sanctions, along the lines discussed above in the context of discouraging successor state proliferation. At a minimum, it can safely be said that intercontinental capability will be a bone of contention in U.S. relations with the successor states.

e. Contain the nuclear contagion.

Nuclear successor states should be encouraged to behave responsibly with respect to more general non-proliferation regime. Even if they themselves have contravened the regime, it is not desirable to have them “off the reservation” contributing to still further proliferation…

...the United States and the international community should insist that nuclear successor states confirm to NPT norms of behavior for nuclear weapons states. They might even be invited to join the NPT regime as nuclear weapons states, although this too might create the appearance of accepting and rewarding proliferation.”

18/ Page 122 - 124

"We have argued that a single nuclear power should emerge from the political change occurring in the Soviet Union, that day-to-day control over the arsenal should remain undisturbed from established patterns, that republics that secede from the Union should be non-nuclear, and that removal of nuclear weapons from these newly independent states should take place as soon as possible in concert with a general nuclear builddown that would not simply transfer all nuclear weapons of the former Soviet Union to the Russian republic.

…It is distinctly possible that the United States will need to cope with outcomes it does not prefer but cannot prevent… Successor state proliferation may occur. These outcomes would result in a more complex nuclear order and would pose more difficult challenges for U.S. policy.

But the U.S. would continue to have a large interest in seeing that such arrangements are as benign as possible and that the adverse consequences of such outcomes are minimized."

"We have argued that a single nuclear power should emerge from the political change occurring in the Soviet Union, that day-to-day control over the arsenal should remain undisturbed from established patterns, that republics that secede from the Union should be non-nuclear, and that removal of nuclear weapons from these newly independent states should take place as soon as possible in concert with a general nuclear builddown that would not simply transfer all nuclear weapons of the former Soviet Union to the Russian republic.

…It is distinctly possible that the United States will need to cope with outcomes it does not prefer but cannot prevent… Successor state proliferation may occur. These outcomes would result in a more complex nuclear order and would pose more difficult challenges for U.S. policy.

But the U.S. would continue to have a large interest in seeing that such arrangements are as benign as possible and that the adverse consequences of such outcomes are minimized."

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh