555 years ago today Erasmus was born.

You've probably heard his name before — but who was Erasmus and why does he matter?

This is the story of history's greatest educator...

You've probably heard his name before — but who was Erasmus and why does he matter?

This is the story of history's greatest educator...

The first thing to know about Erasmus is that he was born in 1469 and died in 1536.

So his life coincided with one of the most turbulent and influential periods in history: the Renaissance, the Reformation, the rise of the printing press...

And Erasmus was involved in it all.

So his life coincided with one of the most turbulent and influential periods in history: the Renaissance, the Reformation, the rise of the printing press...

And Erasmus was involved in it all.

Erasmus was born in Gouda, the Netherlands, and by the age of 14 both his parents had died.

His guardians, who couldn't be bothered to raise the child themselves, sent him to a monastery.

In 1492 he was ordained as a priest, though books interested him much more than preaching.

His guardians, who couldn't be bothered to raise the child themselves, sent him to a monastery.

In 1492 he was ordained as a priest, though books interested him much more than preaching.

Erasmus didn't like monastery life — he was mild by nature, not prone to extremes either of pleasure or restraint.

The rules were too strict, the food wasn't nourishing, and the hours they kept weren't conducive to study.

And, as he later wrote, they weren't very holy:

The rules were too strict, the food wasn't nourishing, and the hours they kept weren't conducive to study.

And, as he later wrote, they weren't very holy:

What concerned Erasmus most was that his colleagues were outwardly religious — they said the right things and wore the right clothes — without being inwardly pious.

He believed in real virtue, not the show of it, and criticised such hypocrisy wherever he saw it:

He believed in real virtue, not the show of it, and criticised such hypocrisy wherever he saw it:

He was both a devout Christian and passionate Classicist, and believed the two could be reconciled.

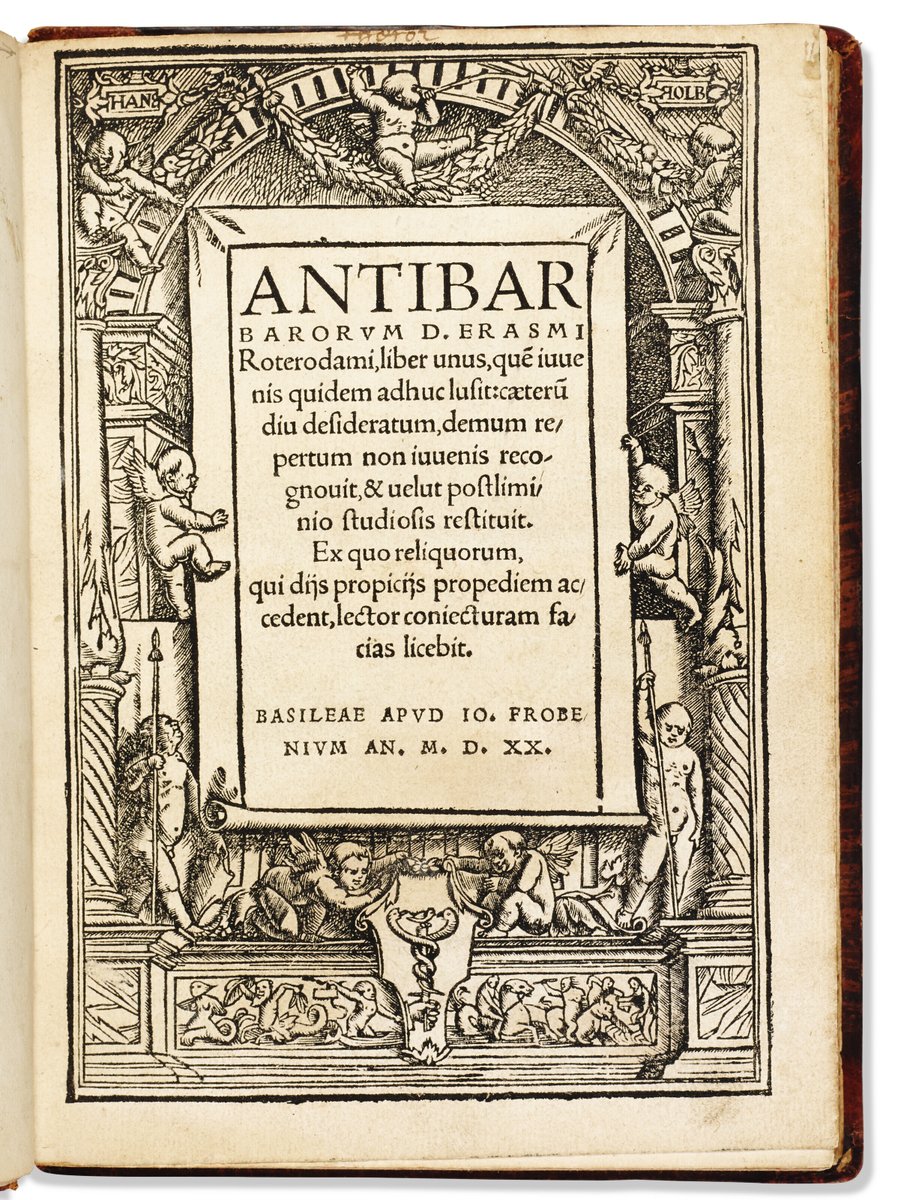

One of his early works, called "Against the Barbarians", criticised monks who refused to read the writers of Ancient Greece and Rome.

For Erasmus there was always a middle way.

One of his early works, called "Against the Barbarians", criticised monks who refused to read the writers of Ancient Greece and Rome.

For Erasmus there was always a middle way.

But Erasmus' moderation didn't make him afraid of controversy — he was uncompromising in his beliefs, whether on faith, war, or monks.

So he always spoke his mind, and always eloquently.

Eventually he was allowed to leave the monastery and start his life as a wandering scholar.

So he always spoke his mind, and always eloquently.

Eventually he was allowed to leave the monastery and start his life as a wandering scholar.

He was also a ruthless satirist.

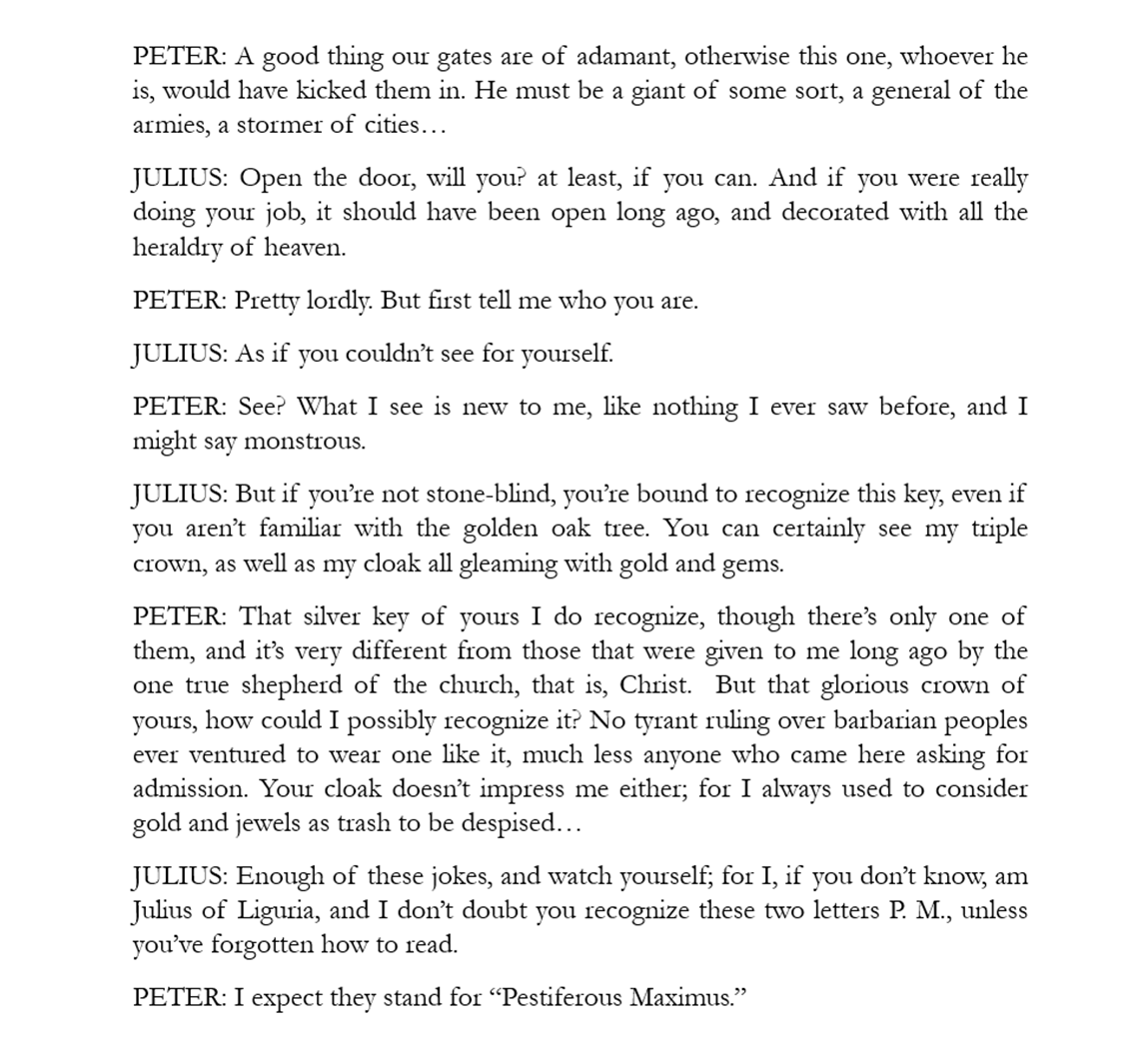

In Praise of Folly is his most famous, but Erasmus wrote many satires, including a rather brutal skewering of Pope Julius II for his wealth and warmongering.

It narrates how the late Pope is denied entry to Heaven by St Peter.

In Praise of Folly is his most famous, but Erasmus wrote many satires, including a rather brutal skewering of Pope Julius II for his wealth and warmongering.

It narrates how the late Pope is denied entry to Heaven by St Peter.

This moral resolution also defined his opposition to war and violence — although Erasmus lambasted the Church, he always argued against conflict as a solution.

After all, his favourite saying came from the Greek poet Pindar:

"War is sweet to those who have not known it."

After all, his favourite saying came from the Greek poet Pindar:

"War is sweet to those who have not known it."

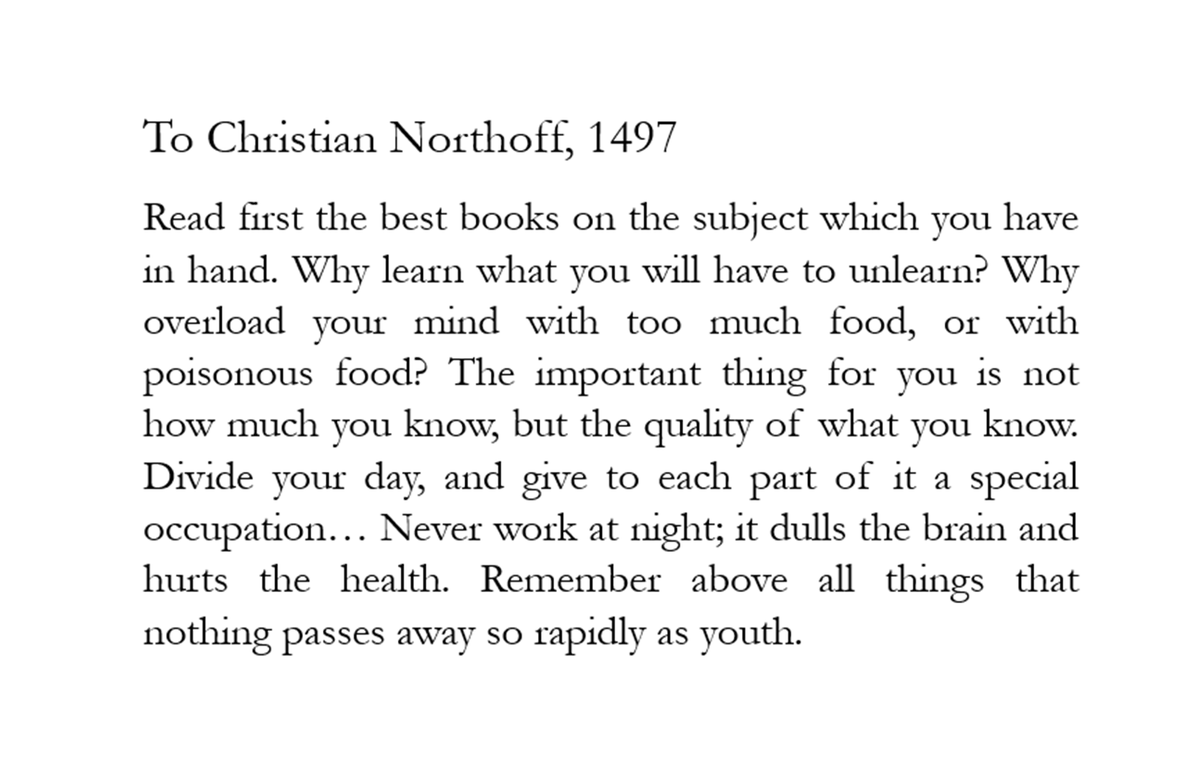

Above all, Erasmus was the ultimate scholar.

He was always working on something and produced a colossal body of work that helped educate a whole continent.

As he once wrote: "When I have a little money, I buy books; and if I have any left, I buy food and clothes."

He was always working on something and produced a colossal body of work that helped educate a whole continent.

As he once wrote: "When I have a little money, I buy books; and if I have any left, I buy food and clothes."

He made a new (& controversial) translation of the New Testament, translated Greek & Roman writers, and wrote countless satires, essays, treatises, and guides for children, students, and adults.

As he said, "to be a teacher is an office second in importance to a King."

As he said, "to be a teacher is an office second in importance to a King."

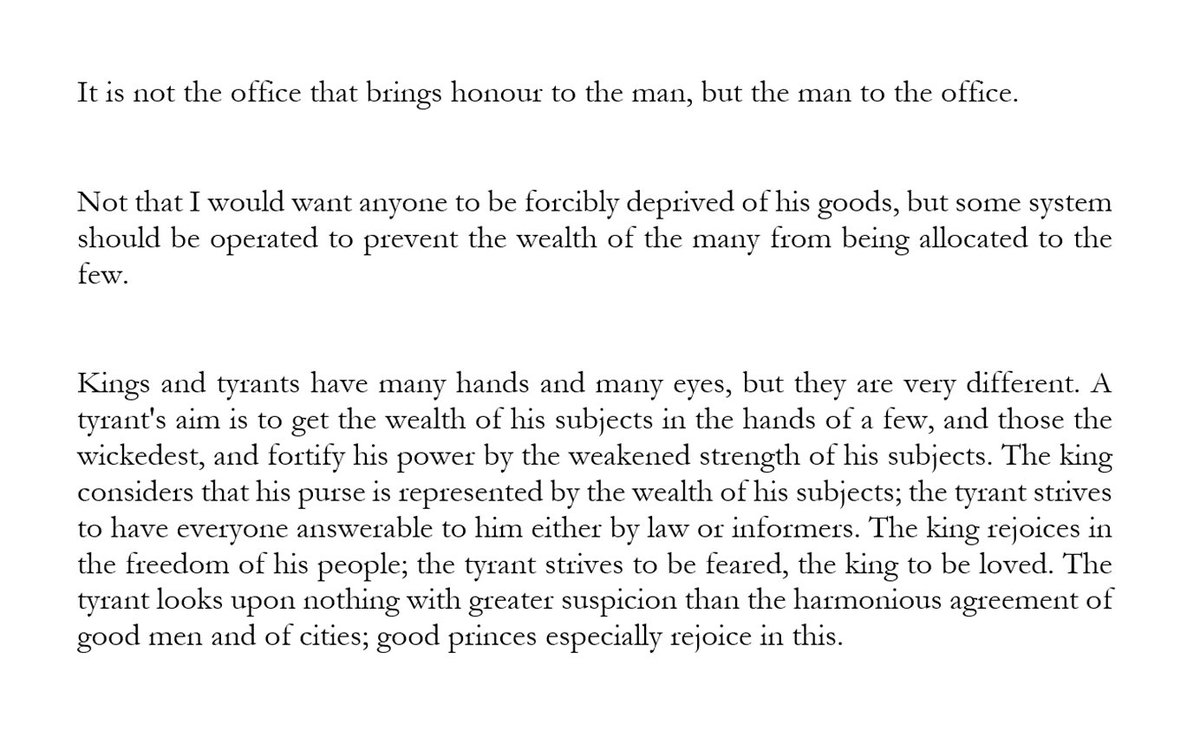

Around the same time Niccolo Machiavelli wrote The Prince, Erasmus wrote his own guide for rulers — and the difference could hardly be more striking.

Where Machiavelli spoke of power games and ruling through fear, Erasmus wrote of justice, love, and peace.

Where Machiavelli spoke of power games and ruling through fear, Erasmus wrote of justice, love, and peace.

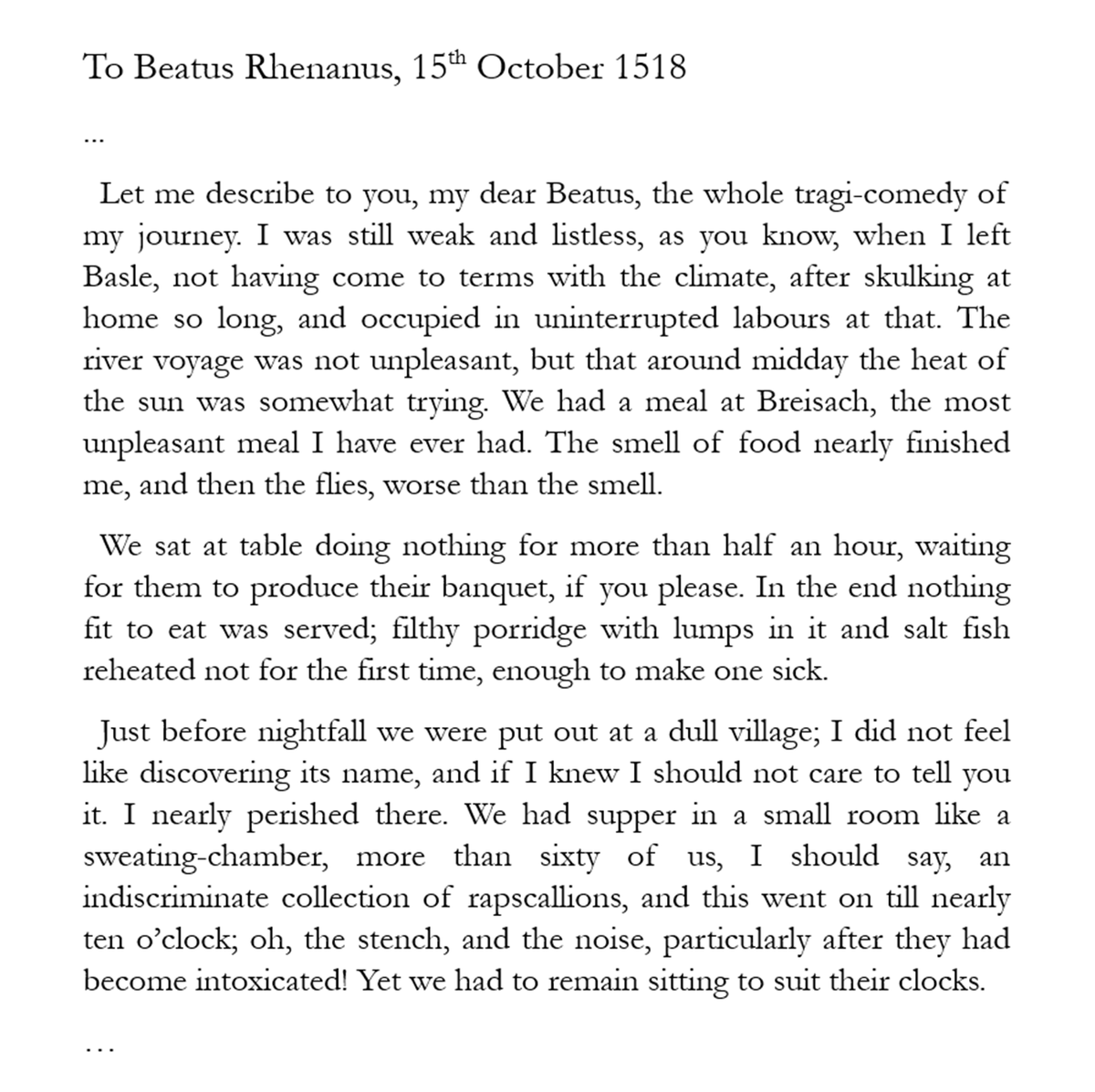

He restlessly travelled Europe in search of patronage, publishers, and friends.

Bologna, Venice, Rome, Freiburg, Basel, Louven, Brussels, London, Oxford, Paris... no wonder he has been called the first European.

Though, as his letters show, he didn't always travel in comfort:

Bologna, Venice, Rome, Freiburg, Basel, Louven, Brussels, London, Oxford, Paris... no wonder he has been called the first European.

Though, as his letters show, he didn't always travel in comfort:

During his travels Erasmus was repeatedly offered bishoprics and salaried roles in royal courts — everybody wanted him in their circle.

But he turned them all down.

What Erasmus wanted, more than anything, was liberty — to pursue his studies and write what he truly believed.

But he turned them all down.

What Erasmus wanted, more than anything, was liberty — to pursue his studies and write what he truly believed.

His correspondents included Popes Julius II, Leo X, and Adrian VI, Henry VII and VIII of England, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, Thomas More, Martin Luther, Albrecht Dürer, and just about every notable person of the early 1500s.

Everybody sought his advice and wisdom.

Everybody sought his advice and wisdom.

Why? Right person, right time — Erasmus' career coincided with the rise of the printing press, and so his wildly popular works could be read across the continent.

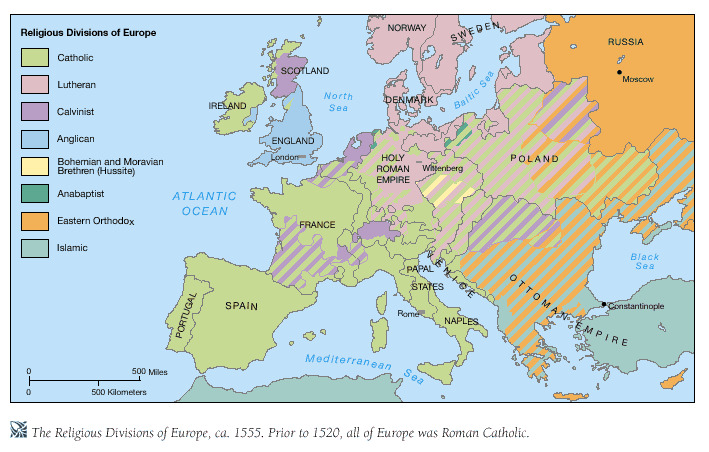

The Reformation might not have happened without his translations, Biblical commentaries, and critique of the Church.

The Reformation might not have happened without his translations, Biblical commentaries, and critique of the Church.

And yet his message was always of reasoned reform, never of revolution and rebellion.

What makes Erasmus special is that he refused to condemn Luther and the other Reformers, but never abandoned the Church.

He saw the truth in both sides and wanted a peaceful solution.

What makes Erasmus special is that he refused to condemn Luther and the other Reformers, but never abandoned the Church.

He saw the truth in both sides and wanted a peaceful solution.

Erasmus was also one of history's greatest friends.

There was hardly anybody he met with whom he did not stay in contact, nor attempt to help out wherever he could, whether kings and popes or teachers and monks.

More than 3,000 of his (usually very witty) letters have survived.

There was hardly anybody he met with whom he did not stay in contact, nor attempt to help out wherever he could, whether kings and popes or teachers and monks.

More than 3,000 of his (usually very witty) letters have survived.

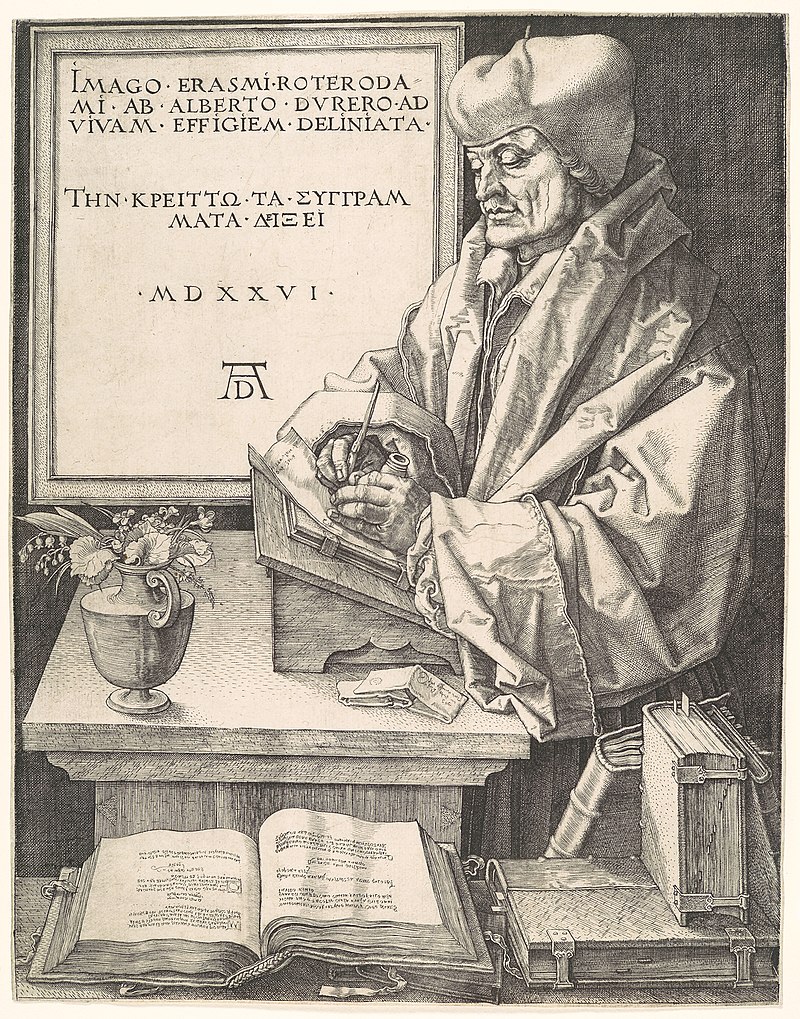

So it seems only fitting that Erasmus was portrayed by some of the greatest artists of the age.

In Hans Holbein the Younger's portrait, from 1523, we see Erasmus the satirist.

A witty, implacable man of letters, wise and perceptive, unimpressed by superficiality and hypocrisy.

In Hans Holbein the Younger's portrait, from 1523, we see Erasmus the satirist.

A witty, implacable man of letters, wise and perceptive, unimpressed by superficiality and hypocrisy.

In Albrecht Dürer's portrait we see a different side: here is the scholar, the restless educator and writer, working (as he always did) while standing up.

This was the man who once said: "the main hope of a nation lies in the proper education of its youth."

This was the man who once said: "the main hope of a nation lies in the proper education of its youth."

Though a devout Christian, Biblical expert, and Classicist, he was not a philosopher.

Erasmus thought abstract argument was divisive — the real work lay in finding common values and using literacy to elevate humankind and help us reach our intellectual and spiritual potential.

Erasmus thought abstract argument was divisive — the real work lay in finding common values and using literacy to elevate humankind and help us reach our intellectual and spiritual potential.

But Erasmus outlived his generation.

By the end of his life Europe had been plunged into civil and religious strife: war, executions, book burnings...

His belief that "it is no great feat to burn a man, but it is a great achievement to persuade him" had fallen on deaf ears.

By the end of his life Europe had been plunged into civil and religious strife: war, executions, book burnings...

His belief that "it is no great feat to burn a man, but it is a great achievement to persuade him" had fallen on deaf ears.

Each side thought they needed Erasmus' support to "win", such was his popularity and influence.

Well, though they all tried to claim him, he remained a resolutely independent intermediary — when he died in 1436 Erasmus had almost become a lone voice for moderation and unity.

Well, though they all tried to claim him, he remained a resolutely independent intermediary — when he died in 1436 Erasmus had almost become a lone voice for moderation and unity.

And that, in brief, is Erasmus, in his own words "a citizen of the world, known to all and to all a stranger."

Popes, kings, & revolutionaries sought his advice and a whole continent read his work — a man devoted to education, friendship, peace, piety, and moderation.

Popes, kings, & revolutionaries sought his advice and a whole continent read his work — a man devoted to education, friendship, peace, piety, and moderation.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh