Ancient Greek thinkers like Socrates and Plato hated democratic elections.

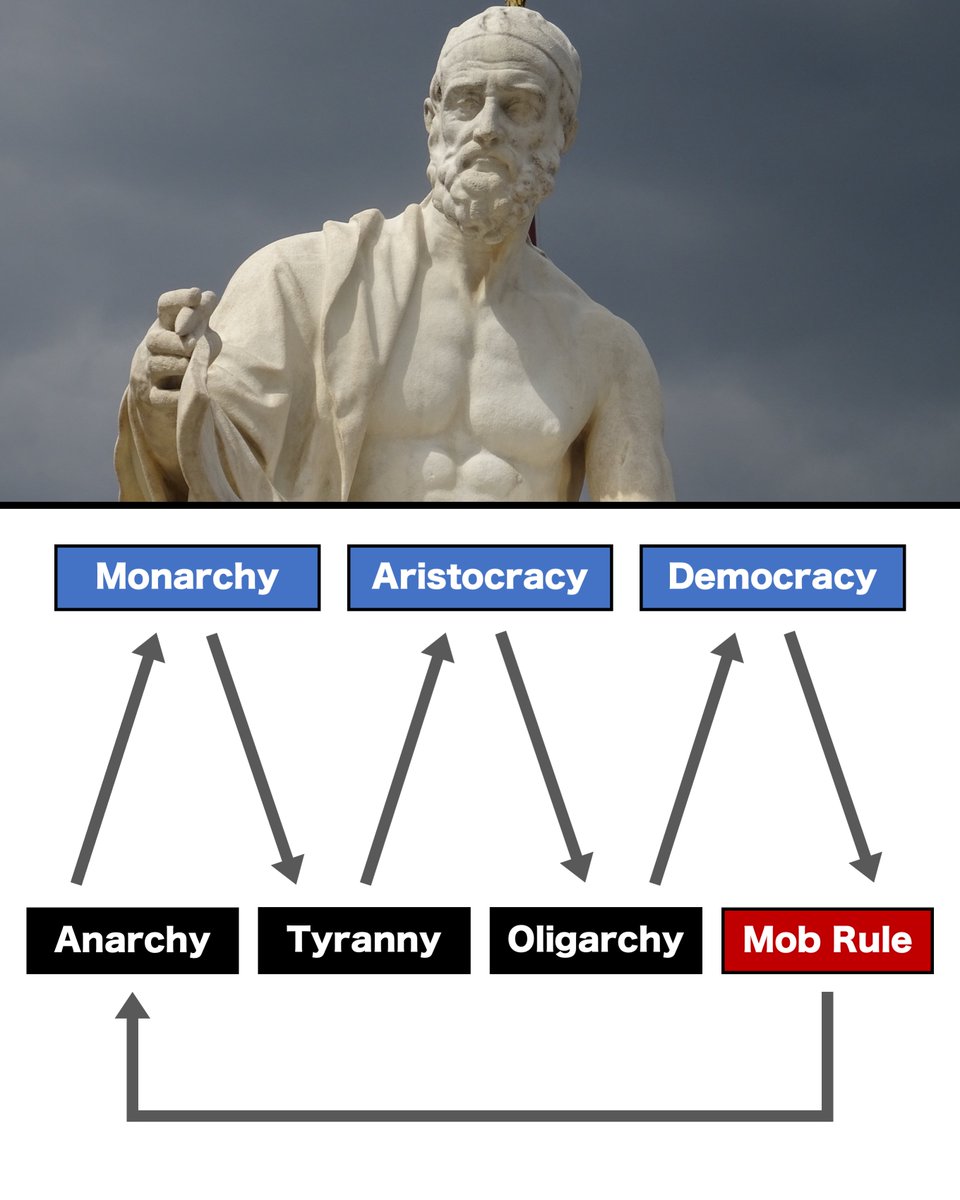

They saw democracy as part of an endless cycle of regimes — destined to slip into mob rule.

But Polybius knew how to break the cycle... (thread) 🧵

They saw democracy as part of an endless cycle of regimes — destined to slip into mob rule.

But Polybius knew how to break the cycle... (thread) 🧵

Socrates likened the state to a ship. The uneducated voting in elections is like a ship taken over by a crew with no knowledge of sailing.

When selecting a captain, the crew is easily swayed by whoever is best at persuasion — not navigation.

When selecting a captain, the crew is easily swayed by whoever is best at persuasion — not navigation.

Voting, thought Socrates, is a skill to be learned.

In Plato's 5 forms of government, democracy ranks only above tyranny, which it will inevitably become.

Why?

In Plato's 5 forms of government, democracy ranks only above tyranny, which it will inevitably become.

Why?

Systems that maximize freedom and equality lead us to pursue selfish pleasures, not the common good.

When votes are cast based not on what is good, but what is desired by the masses, demagogues emerge.

When votes are cast based not on what is good, but what is desired by the masses, demagogues emerge.

Like the ship, he with the best rhetoric wins by playing on selfish interests and emotions, not reason.

Once in charge, he creates a system of dependancy: "He is always stirring up some war so that the people may be in need of a leader..."

Once in charge, he creates a system of dependancy: "He is always stirring up some war so that the people may be in need of a leader..."

So, Plato thought the ideal system was aristocracy.

Voting should be a profession like any other, and only those with expertise should participate. Those with knowledge of "good" (the philosophers) should rule.

Voting should be a profession like any other, and only those with expertise should participate. Those with knowledge of "good" (the philosophers) should rule.

But Plato admitted this too is doomed to fail. When aristocratic rulers are no longer motivated purely by reason, but prioritize public approval, things fall apart again.

200 years later, a man named Polybius proposed a brilliant solution...

200 years later, a man named Polybius proposed a brilliant solution...

Polybius argued that regimes were in an endless cycle, and the three basic forms of government are destined to degenerate into their lower forms — and lead back to anarchy.

But there's a way to fix it...

But there's a way to fix it...

To break the cycle, you need to combine elements of each system. Polybius admired this in the Roman Republic:

Consuls (monarch-like leaders), Senate (aristocratic body), and Assemblies (democratic element).

Consuls (monarch-like leaders), Senate (aristocratic body), and Assemblies (democratic element).

This idea of separation of powers was developed by Montesquieu, and led ultimately to the American system devised by the Founding Fathers:

The Presidency (monarch-like), the Senate (aristocratic) and the House (democratic) — plus the Judiciary to add balance.

The Presidency (monarch-like), the Senate (aristocratic) and the House (democratic) — plus the Judiciary to add balance.

There isn't a true aristocratic element (by birth or wealth), but Senators are in some sense.

They have longer terms than representatives, represent states not populations, and were originally chosen by state legislatures, not the public (until 1913).

They have longer terms than representatives, represent states not populations, and were originally chosen by state legislatures, not the public (until 1913).

Going back to Socrates, his concern was that democracies are unsafe in the hands of ordinary people.

But instead of a privileged voting class, he wanted everyone to think rationally enough to become worthy of participating.

But instead of a privileged voting class, he wanted everyone to think rationally enough to become worthy of participating.

Democracy, he thought, is only as good as the education system surrounding it — and Jefferson had much the same concern:

"If a nation expects to be ignorant & free, in a state of civilisation, it expects what never was & never will be".

"If a nation expects to be ignorant & free, in a state of civilisation, it expects what never was & never will be".

If these threads interest you, I go deeper in my free newsletter every week — do NOT miss tomorrow.

93,000+ people read it: history, art and culture 👇

culture-critic.com/welcome

93,000+ people read it: history, art and culture 👇

culture-critic.com/welcome

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh