The negative results for the phase II BC007 trial are disappointing but not surprising, given the outcome measures they used. What is an outcome measure, what was the problem with this trial's design, and what does that mean for our future advocacy?

https://twitter.com/realfrankbecker/status/1856644776080150619

A randomised controlled trial works as follows: we measure how well people are before treatment, and then we give one group the treatment, and another group a placebo. Then, we measure how well each group is, and we compare them.

The "outcome measure" is the measure we use to measure how well people are. So, it's extremely important to use an outcome measure that can correctly identify improvements and deteriorations in the trial participants

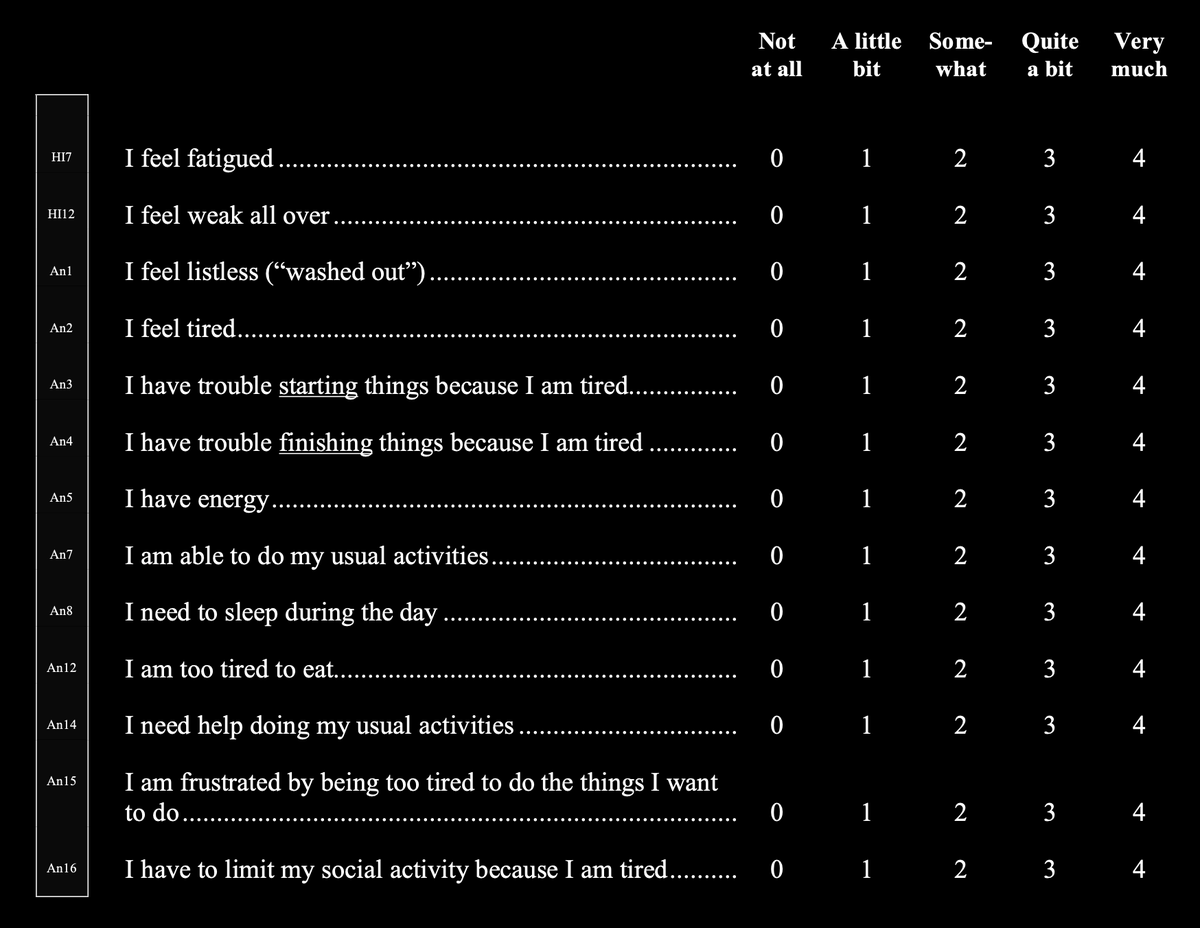

The BC007 trial used the FACIT-FS questionnaire as the primary outcome measure (the measure used to decide whether or not the trial was a success). Here is the FACIT-FS: (careful: bright) facit.org/_files/ugd/c0d…

As will be obvious to anyone with Long COVID, this questionnaire cannot record the kinds of improvements or worsenings that we see in the community. For instance, how would you describe someone going from moderate to severe ME using this questionnaire?

How would you describe someone whose cardiovascular problems have improved? How would you describe someone who's regained the capacity to read but whose physical function has stayed the same? Etc.

The trial also used secondary outcome measures: things they measure but that don't count as an answer to the question of whether the treatment was successful.

In a nutshell, they measured cognitive function, number of symptoms, number of hours slept, reported quality of sleep,

In a nutshell, they measured cognitive function, number of symptoms, number of hours slept, reported quality of sleep,

Distance walked in six minutes, some lab tests, and quality of life using this scale:

(full list of outcome measures here: -- careful: bright) clinicaltrialsregister.eu/ctr-search/tri…

(full list of outcome measures here: -- careful: bright) clinicaltrialsregister.eu/ctr-search/tri…

The lab tests are not very precisely described, which is a shame.

So far, Berlin Cures have only said that the trial was unsuccessful, and haven't released their full data. I don't know whether they will publish their results, or make their data published. (Does anyone know?)

So far, Berlin Cures have only said that the trial was unsuccessful, and haven't released their full data. I don't know whether they will publish their results, or make their data published. (Does anyone know?)

This shows that having adequate primary and secondary outcome measures is absolutely crucial to get an accurate idea of how helpful various interventions really are. With a trial like this using FACIT-FS, we were never going to get results

Which outcome measures should trials use? That will depend partly on what the trial tries to measure. But personally, I think that any trial for Long COVID in general and for ME should use the FUNCAP (usercontent.one/wp/www.funcap.… --careful: bright)

x.com/elle_carnitine…

x.com/elle_carnitine…

They should use this alongside non-patient-reported outcomes such as cardiovascular events, various lab markers possibly related to the intervention (immune markers, pathogen markers, coagulation markers, etc.)

If we want institutional science to deliver a safe and effective treatment, I think we will need to get up in their business about how they design their trials, and in particular, which outcome measures they use. Otherwise we will keep getting useless results like this

This thread was brought to you by discussions with @FvRhijn, @LauradeVri90078, Xandra Westerhuis, and Jon-Ruben van Rhijn ---we have a paper on outcome measures in Long COVID clinical trials hopefully coming out soon!

CORRECTION. @FvRhijn points out that the scale used as a primary outcome measure is not the full scale I pasted above, but a sub scale containing only items about fatigue. Here is the actual primary outcome measure:

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

![I’m not sure if it’s like a certain type of person who gets CFS [...] apparently people who’ve got erm ... IBS have erm specially sensitised brains basically, so they are much more sensitive to say like chemicals [...] so they have symptoms even though nothing’s wrong. So I mean it could be erm a similar scenario with CFS ... (P109, Male, 5th Year)](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/GWpGAI6WMAAKb4Y.png)

![Like every patients is different because how, like coping mechanisms [...] so someone [...] might just be able to work through it and try ... like pretty much have a normal life [...] whereas another person might [...] end up in bed all day. So it’s ... and there’s people in between so ... (P104, Male, 4th Year)](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/GWpGGY8WAAAfkzC.png)