(I tried to post this thread a couple of weeks ago but I didn't get to finish it smh)

For the last 8 years, over at @Steplab_co, we've been working on a project to codify HIGHLY EFFECTIVE TEACHING.

A long-ish summary of what we've learned:

↓

For the last 8 years, over at @Steplab_co, we've been working on a project to codify HIGHLY EFFECTIVE TEACHING.

A long-ish summary of what we've learned:

↓

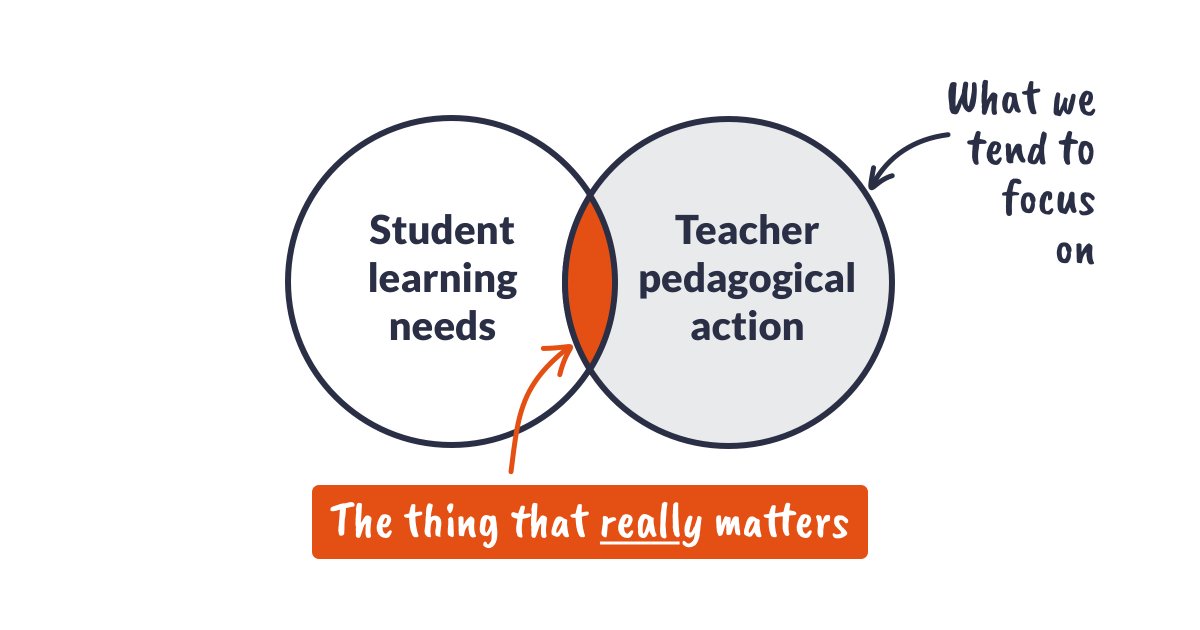

@Steplab_co One of the essential ingredients of effective professional development is the provision of concrete & granular teaching 'strategies'.

These can be used as examples of 'what good looks like', which teachers can translate for their context, and practise in a productive way.

These can be used as examples of 'what good looks like', which teachers can translate for their context, and practise in a productive way.

@Steplab_co However, it's also critical to help teachers see how such granular strategies fit into their broader teaching repertoire.

*Context* is as important as *content*.

Eg: How Cold Call fits into the wider goal of maximising pupil thinking, alongside Wait Time and other strategies.

*Context* is as important as *content*.

Eg: How Cold Call fits into the wider goal of maximising pupil thinking, alongside Wait Time and other strategies.

@Steplab_co Now, developing a suite of such strategies, and organising them in a meaningful hierarchy is no small task.

It's effectively an effort to codify effective teaching, one of the most complex and challenging jobs ever devised 🤯

It's effectively an effort to codify effective teaching, one of the most complex and challenging jobs ever devised 🤯

@Steplab_co For nearly a decade, we've been working with schools on exactly this—a gargantuan project to build out a library of concrete, granular teaching strategies.

We call them 'steps'.

Hence 'Steplab' 🪜

We call them 'steps'.

Hence 'Steplab' 🪜

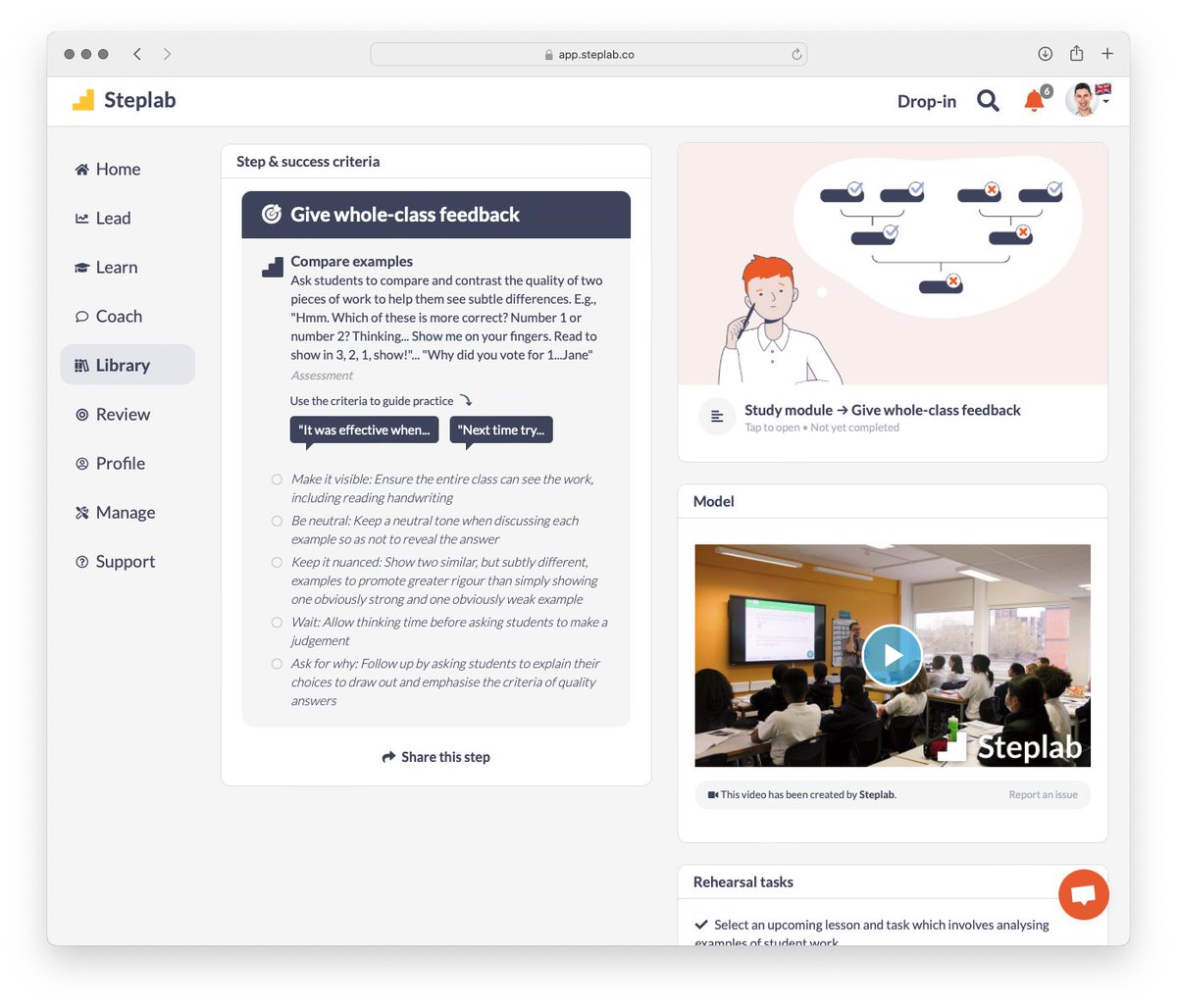

@Steplab_co So far, we have over 600 steps, covering core teaching practices.

(as well as specialist steps for early years, KS1, pastoral, teaching assistants, and more coming)

Each step has success criteria, model videos, practice tasks, and an overview of related evidence/theory.

(as well as specialist steps for early years, KS1, pastoral, teaching assistants, and more coming)

Each step has success criteria, model videos, practice tasks, and an overview of related evidence/theory.

@Steplab_co Steplab provides a *load* of tools to help schools improve teaching—our steps sit at the heart of ALL of these.

(Last year alone, schools set over 300,000 steps)

The better our steps are, the easier and quicker schools can help their teachers improve.

(Last year alone, schools set over 300,000 steps)

The better our steps are, the easier and quicker schools can help their teachers improve.

@Steplab_co Over the last couple of years, we've begun to really double down on the quality and coherence of our steps.

Here's what we did and why...

(I warned you this was a long thread)

Here's what we did and why...

(I warned you this was a long thread)

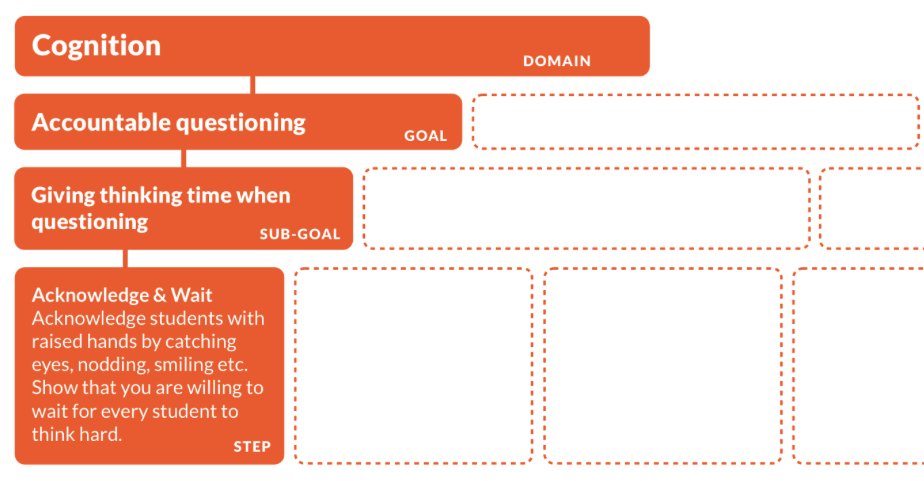

@Steplab_co First up, a little detour into how our steps are organised.

With over 600 steps, and the need to provide context for all of them, we've settled on a 'tree' structure.

Which basically breaks teaching down into successively smaller pieces, so they can be easily practised.

With over 600 steps, and the need to provide context for all of them, we've settled on a 'tree' structure.

Which basically breaks teaching down into successively smaller pieces, so they can be easily practised.

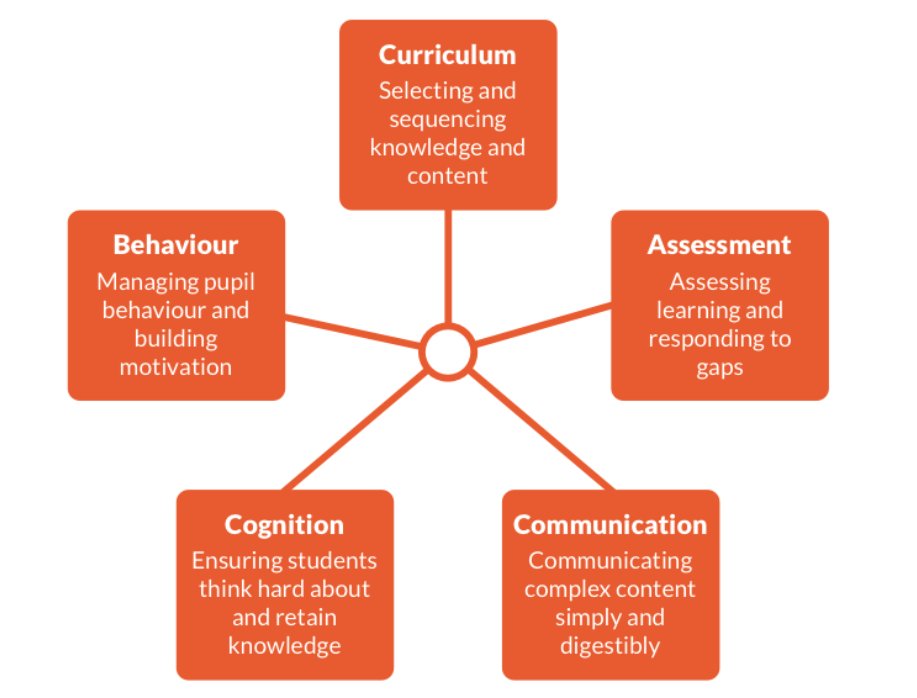

@Steplab_co FYI here are the 5 'top-level' areas, in their original semantic structure:

(we'll unveil the new and improved version later in this thread)

(we'll unveil the new and improved version later in this thread)

@Steplab_co So, what was unclear? There were 4 main things:

1. The articulation of steps lacked concision

2. The semantic structure between levels was inconsistent

3. We lacked 'sticky shorthands' to help folks discuss things

4. The top level framework was too abstract

Let's look at each.

1. The articulation of steps lacked concision

2. The semantic structure between levels was inconsistent

3. We lacked 'sticky shorthands' to help folks discuss things

4. The top level framework was too abstract

Let's look at each.

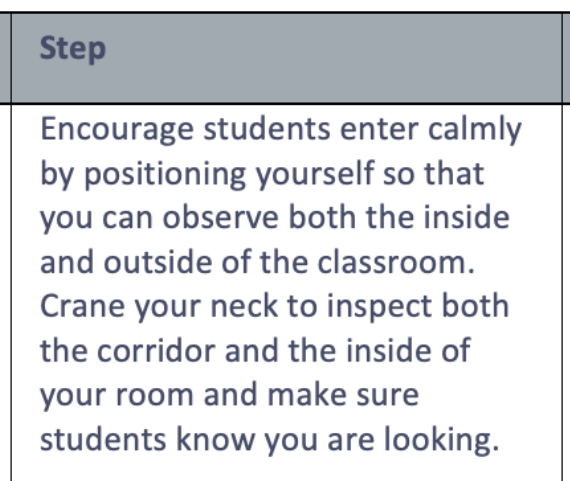

@Steplab_co 1/ Step concision.

Here's an old step. It contains a lot of words. Every word incurs a cost in terms of time and cognitive processing.

If we could make these more concise, we would make coaching more efficient.

Here's an old step. It contains a lot of words. Every word incurs a cost in terms of time and cognitive processing.

If we could make these more concise, we would make coaching more efficient.

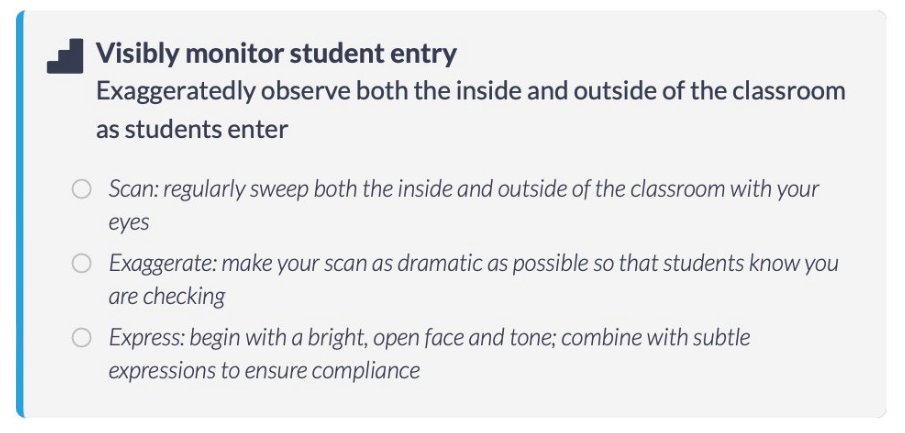

@Steplab_co Here's the new version.

It contains fewer words. AND we've added a sticky 'shorthand' name for the step, so teachers can talk about it without having to describe the whole step.

*Ritual pause to honour Big Dawg @Doug_Lemov, the grandfather of the sticky shorthand.

It contains fewer words. AND we've added a sticky 'shorthand' name for the step, so teachers can talk about it without having to describe the whole step.

*Ritual pause to honour Big Dawg @Doug_Lemov, the grandfather of the sticky shorthand.

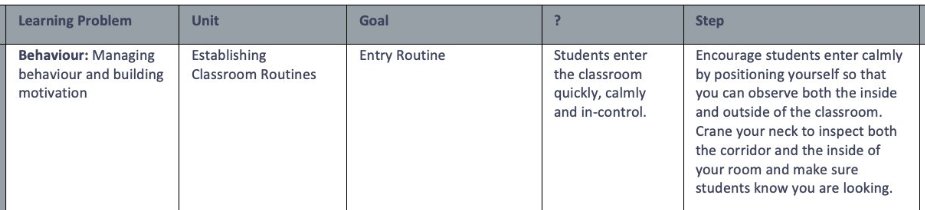

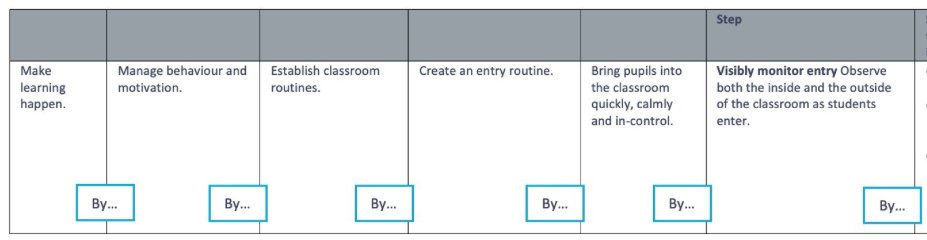

@Steplab_co @Doug_Lemov 2/ Consistent semantic structure

Here's the old structure. As you can see, the framing of each of these levels is highly inconsistent. This makes it hard to mentally 'nest' the context.

Here's the old structure. As you can see, the framing of each of these levels is highly inconsistent. This makes it hard to mentally 'nest' the context.

@Steplab_co @Doug_Lemov Here's the new version.

You can see that each level is now framed in a similar 'directive' manner.

Which enables coaches to have conversations about the context— relationship *between* levels.

You can see that each level is now framed in a similar 'directive' manner.

Which enables coaches to have conversations about the context— relationship *between* levels.

@Steplab_co @Doug_Lemov Eg: teachers can talk about:

→ Making learning happen *by* managing pupil behaviour and motivation

→ Managing behaviour and motivation *by* establishing classroom routines

→ Establish classroom routines *by* creating an entry routine

→ Etc.

→ Making learning happen *by* managing pupil behaviour and motivation

→ Managing behaviour and motivation *by* establishing classroom routines

→ Establish classroom routines *by* creating an entry routine

→ Etc.

@Steplab_co @Doug_Lemov Or we can work back up the hierarchy:

→ Create an entry routine *to* establish classroom routines

→ Establish classroom routines *to* manage behaviour and motivation

→ Manage pupil behaviour and motivation *to* make learning happen

→ Etc.

→ Create an entry routine *to* establish classroom routines

→ Establish classroom routines *to* manage behaviour and motivation

→ Manage pupil behaviour and motivation *to* make learning happen

→ Etc.

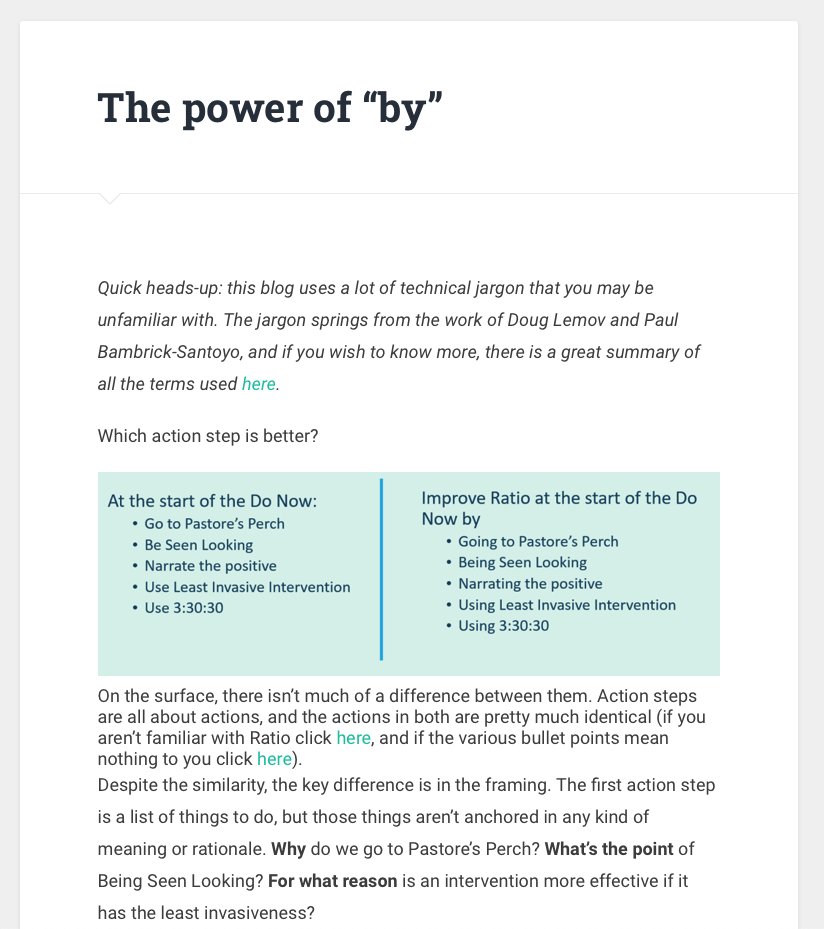

@Steplab_co @Doug_Lemov ASIDE

@Adamboxer1 has some brilliant ideas on using connectives to help teachers build better mental models, eg. ⤵️

achemicalorthodoxy.co.uk/2021/04/27/the…

@Adamboxer1 has some brilliant ideas on using connectives to help teachers build better mental models, eg. ⤵️

achemicalorthodoxy.co.uk/2021/04/27/the…

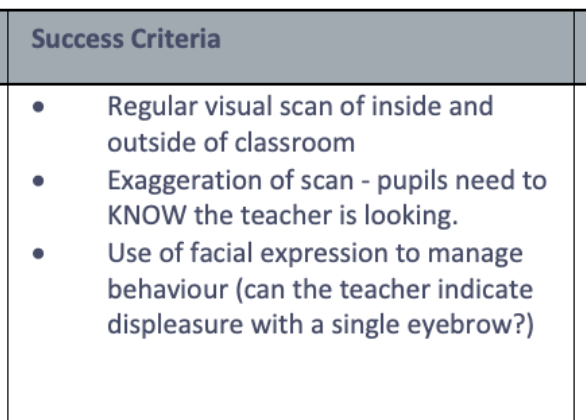

@Steplab_co @Doug_Lemov @adamboxer1 3/ Sticky shorthands

We've talked already about how we've adopted this for our steps. But we also decided to use it for all our success criteria for each step.

Before and after here:

We've talked already about how we've adopted this for our steps. But we also decided to use it for all our success criteria for each step.

Before and after here:

@Steplab_co @Doug_Lemov @adamboxer1 4/ Abstract framework

For all this to develop adaptive expertise, we realised we needed an overarching model to hang everything around.

The 'Unified Teaching and Learning Framework' was born 🔥

(huge shoutout to @olicav for letting us build on his original diagram 🙏)

For all this to develop adaptive expertise, we realised we needed an overarching model to hang everything around.

The 'Unified Teaching and Learning Framework' was born 🔥

(huge shoutout to @olicav for letting us build on his original diagram 🙏)

@Steplab_co @Doug_Lemov @adamboxer1 @olicav Mary Kennedy (2016b) argues that when teachers work on a new technique—unless they understand the *purpose* that the technique serves—they can easily use it at the wrong time in the wrong way.

In short, we can end up building rigid expertise (and seeding lethal mutations).

In short, we can end up building rigid expertise (and seeding lethal mutations).

@Steplab_co @Doug_Lemov @adamboxer1 @olicav Organising effective teaching around a model of learning can help mitigate this risk...

As the purpose of each technique is embedded in the very *structure* of the hierarchy.

And if this hierarchy is explored during training, then we're more likely to build adaptive expertise.

As the purpose of each technique is embedded in the very *structure* of the hierarchy.

And if this hierarchy is explored during training, then we're more likely to build adaptive expertise.

@Steplab_co @Doug_Lemov @adamboxer1 @olicav IMPORTANT

I'm not saying that this framework is a *perfect* model of teaching & learning...

(teaching is WAAY more complex than this)

...just that having a model, and one that is sufficiently simple and aligned to the evidence of how people learn, can be mega powerful.

I'm not saying that this framework is a *perfect* model of teaching & learning...

(teaching is WAAY more complex than this)

...just that having a model, and one that is sufficiently simple and aligned to the evidence of how people learn, can be mega powerful.

@Steplab_co @Doug_Lemov @adamboxer1 @olicav And so there you have it. A deep dive into our continued efforts to codify effective teaching and what we've been #building over at Steplab.

If you're interested in learning more about the evidence underpinning our approach, check out our white paper ⤵️

steplab.co/resources/pape…

If you're interested in learning more about the evidence underpinning our approach, check out our white paper ⤵️

steplab.co/resources/pape…

@Steplab_co @Doug_Lemov @adamboxer1 @olicav And if you'd like to find out more about how @Steplab_co is helping improve teaching at 100s of school school, just drift over here (we LOVE giving demos):

→

👊steplab.co

→

👊steplab.co

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh