A friend asked me to explain DNA, RNA, and epigenetics. he said that others had tried before, but it didn’t click for him.

I happen to play the piano, so I gave him a simple, albeit imperfect, analogy.

After this analogy, he finally understood! Here’s the piano analogy.

🧵

I happen to play the piano, so I gave him a simple, albeit imperfect, analogy.

After this analogy, he finally understood! Here’s the piano analogy.

🧵

Imagine a piano with 30,000 keys. Each key represents a gene.

Nearly all of your somatic cells have the exact same piano—the same keys, the same genes. So why does a nerve cell look different from a cheek cell?

Because they’re playing different pieces on the identical pianos.

Nearly all of your somatic cells have the exact same piano—the same keys, the same genes. So why does a nerve cell look different from a cheek cell?

Because they’re playing different pieces on the identical pianos.

The piano is just a set of keys! The music—the composition—is the result of playing specific keys in a particular sequence and rhythm.

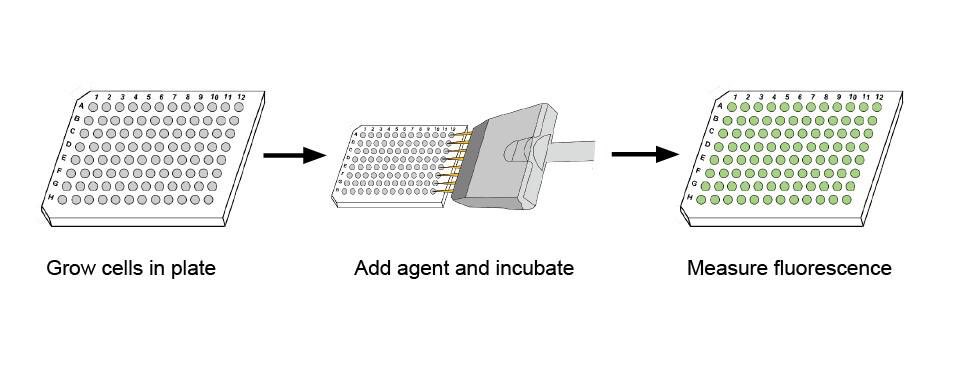

Pressing a key to play a note is like expressing a gene to produce mRNA.

Pressing a key to play a note is like expressing a gene to produce mRNA.

Playing a note multiple times => multiple mRNA molecules from that gene.

Within a cell, the pattern of mRNA expression changes over time, just like the notes change over time in a musical score.

At any given moment, a fraction of the keys are being played.

Within a cell, the pattern of mRNA expression changes over time, just like the notes change over time in a musical score.

At any given moment, a fraction of the keys are being played.

Epigenetics is like the way the piano is played.

Some keys are easy to press; others harder to reach or require more effort.

Some keys might be muted or locked in certain cells; impossible to play there but functional in others. some keys play indirectly when you press another.

Some keys are easy to press; others harder to reach or require more effort.

Some keys might be muted or locked in certain cells; impossible to play there but functional in others. some keys play indirectly when you press another.

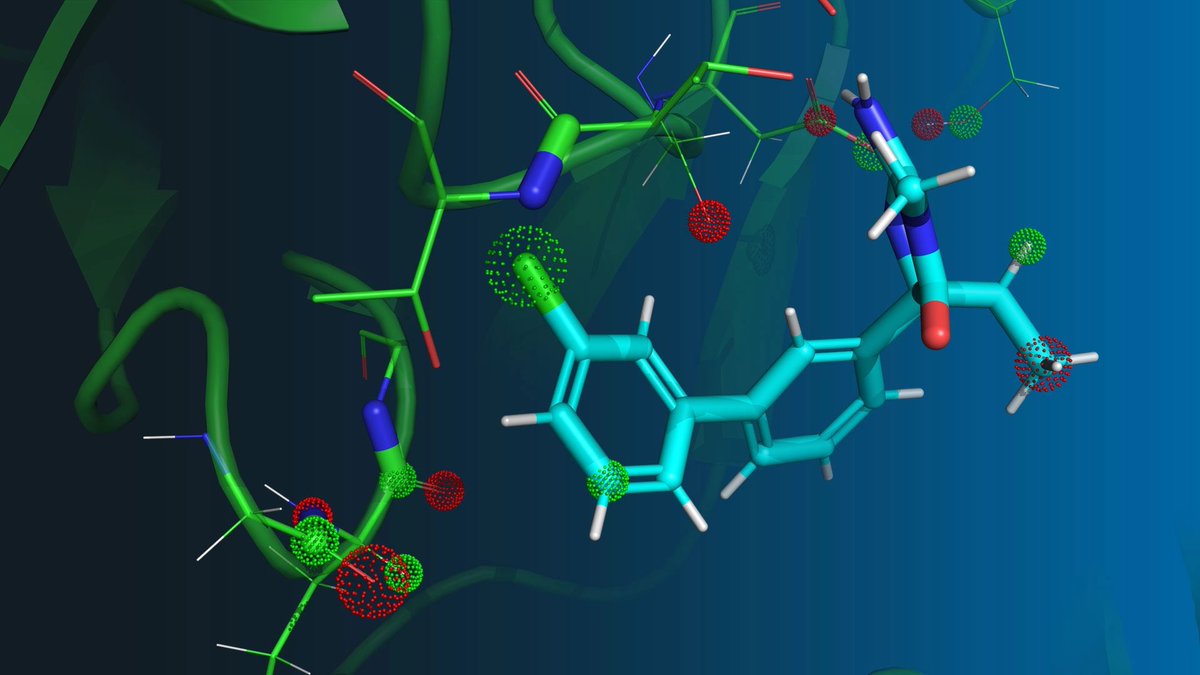

These differences to a key, like heavier key, muted key, hard to reach key, can be written on the keys themselves (for one cell). Here’s a register of various epigenetic changes in “keys”

As before, this register may change based on cell, type of cell, etc.

As before, this register may change based on cell, type of cell, etc.

These performances are recorded into songs, much like proteins are synthesized based on mRNA templates.

Proteins are the final products—they have specific structures and functions, giving cells their unique characteristics.

The mRNA (the notes you play) might degrade quickly, but the proteins (the recorded songs) can remain in the cell as long as needed.

Proteins are the final products—they have specific structures and functions, giving cells their unique characteristics.

The mRNA (the notes you play) might degrade quickly, but the proteins (the recorded songs) can remain in the cell as long as needed.

So, even though every cell has the same “piano,” the diverse “music” played leads to different cell types and functions.

I hope this analogy makes DNA, RNA, and epigenetics clearer!

I hope this analogy makes DNA, RNA, and epigenetics clearer!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh