I've worked as a military historian for 10 years, teaching undergrads and ROTC cadets.

The thing that many students get wrong about war is focusing on a tactic or piece of technology. Single technologies rarely revolutionize war overnight. You have to take a broader look. 🧵1/25

The thing that many students get wrong about war is focusing on a tactic or piece of technology. Single technologies rarely revolutionize war overnight. You have to take a broader look. 🧵1/25

https://twitter.com/brandan_buck/status/1861555248482963789

Today you see this in conversations about Elon Musk and the F-35. Futurists ask: Should we ditch the F-35 for drone swarms? Will drones make it impossible for infantry to operate on the battlefield? Will all future combat systems be autonomous? 2/25

https://x.com/elonmusk/status/1860574377013838033

As human beings, we like focusing on individual topics and items. Single pieces of technology, a "new shiny thing" have often seemed to promise change. What do you need to win? What one weapon system will prove to be a game changer? 3/25

You can see this in the rise of "how would you even beat this" questions, which seem to be asked of the Macedonian Phalanx every year or so.

More frequently than tactics, though, you see it asked of technology. We love tech. 4/25

More frequently than tactics, though, you see it asked of technology. We love tech. 4/25

https://x.com/thinkingwest/status/1861045071388295504

Students can tell me the specifications on rifles, tanks, planes, and ships from the Second World War from memory. Especially the Tiger I. Statistics of the rates of vehicle production by the various nations of the Second World War seem to be less fun to memorize. 5/25

We've seen this in Ukraine. First, it was Turkish Bayraktar.

Then HIMARS

Then modern western MBTs

Then ATACMS

Then POV drones

Then F-16s

Now, all of these weapons helped Ukraine in the war. Ukrainian soldiers and airmen appreciate their capabilities. 6/25

Then HIMARS

Then modern western MBTs

Then ATACMS

Then POV drones

Then F-16s

Now, all of these weapons helped Ukraine in the war. Ukrainian soldiers and airmen appreciate their capabilities. 6/25

https://x.com/Cappyarmy/status/1859632054599811308

But none of these weapons has completely changed the game, and proved a talismanic key to victory. And that shouldn't surprise us: individual weapon systems rarely prove to be a complete game changer in war. Individual weapon systems rarely revolutionize the battlefield. 7/25

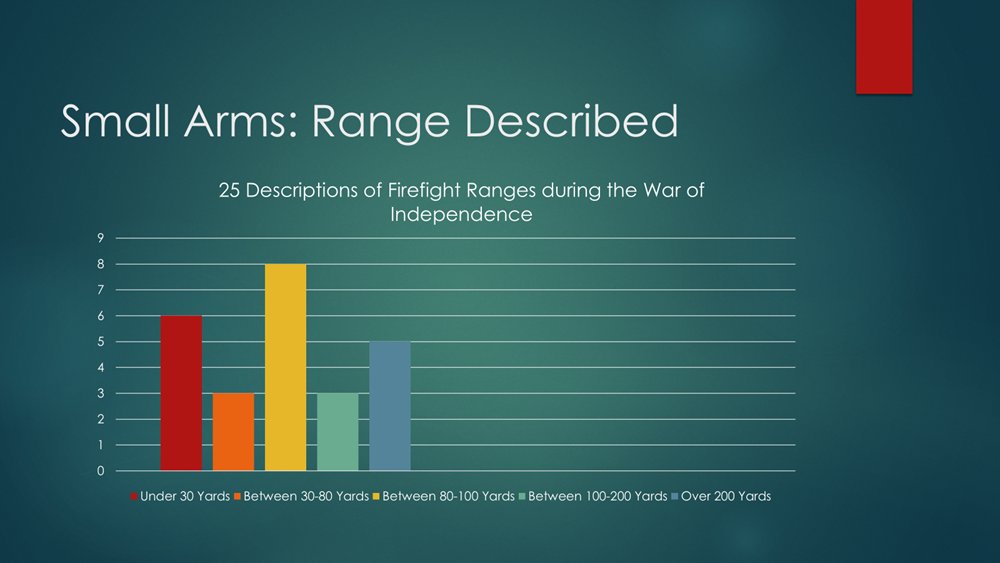

To see this in the past, we can look at the begins of the early modern warfare in the 1500s, as gunpowder weapons became more common in European warfare. In the early 1500s, artillery and to some extent, small arms, were changing the battlefield. 8/25

Military theorists, then as now, were fascinated by the way that technology was changing warfare, and began to argue that a total revolution had occurred. Niccolò Machiavelli commented on this in Chapter 17 of his Discourses: 9/25

"For it is said that by reason of these fire-arms men can no longer use or display their personal valour as they could of old; that there is greater difficulty now than there was in former times in joining battle; that the tactics followed then cannot be followed now; and that in time all warfare must resolve itself into a question of artillery." 10/25

Well, what did Machiavelli think of these claims? "

As to the ... assertion, that armies can no longer be brought to engage one another, and that war will soon come to be carried on wholly with artillery, I maintain that this allegation is utterly untrue[.]" 11/25

As to the ... assertion, that armies can no longer be brought to engage one another, and that war will soon come to be carried on wholly with artillery, I maintain that this allegation is utterly untrue[.]" 11/25

He continued that battles would "always" be decided by hand-to-hand combat. Who was right? Obviously, neither Machiavelli or his opponents. Firearms * did * come to dominate the battlefield, but melee combat continued to play an important role in warfare for over 200 years. 12/25

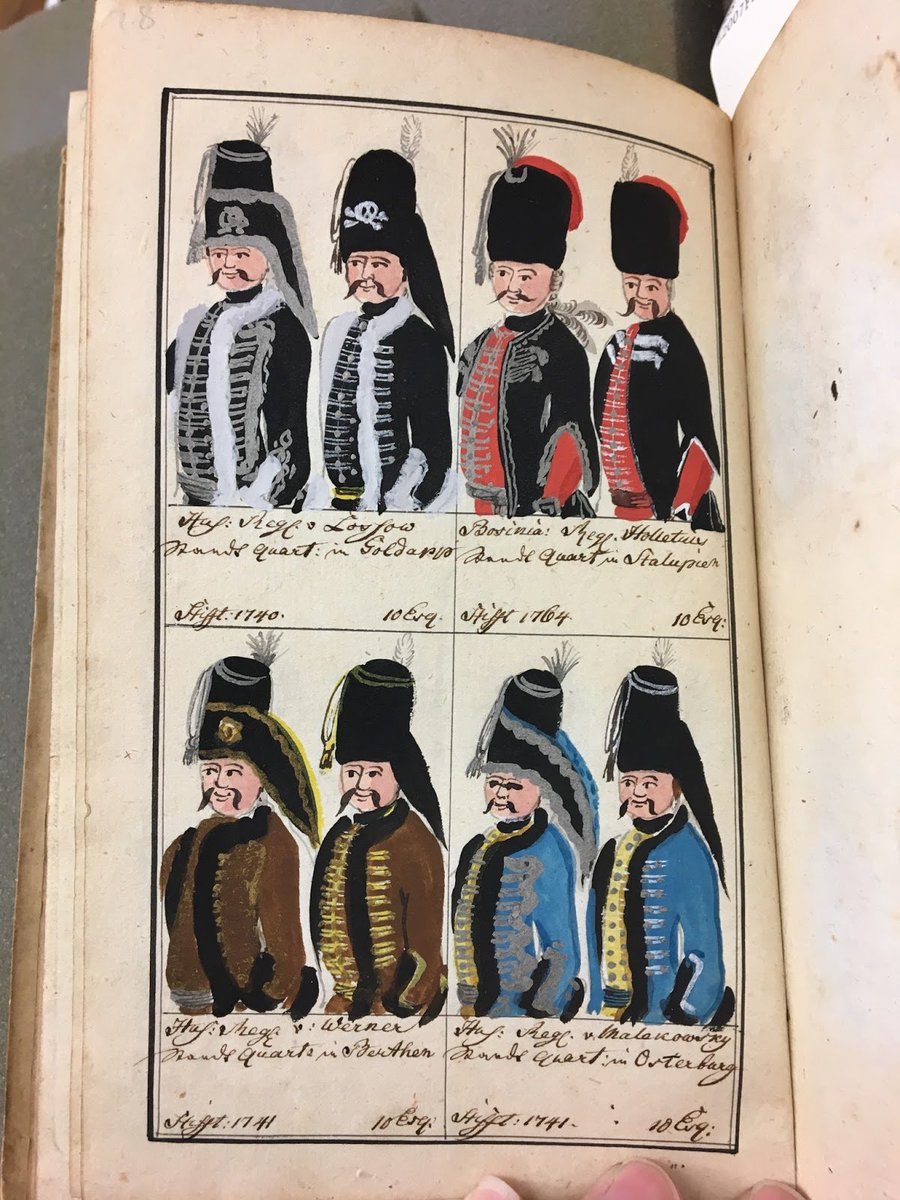

You see the same progression in terms of cavalry: the ingredients to make cavalry a less decisive combat arm existed in the 1500s, but that transition was not fully complete until the 1930s/40s. It takes TIME to supplant weapon systems. 13/25

https://x.com/KKriegeBlog/status/1750344560696238269

Completely underestimating weapon systems that are in the process of being supplanted is a dangerous thing. The French and Reichsarmee infantry at Rossbach would have been shocked to learn that cavalry and melee combat were a thing of the past. 14/25

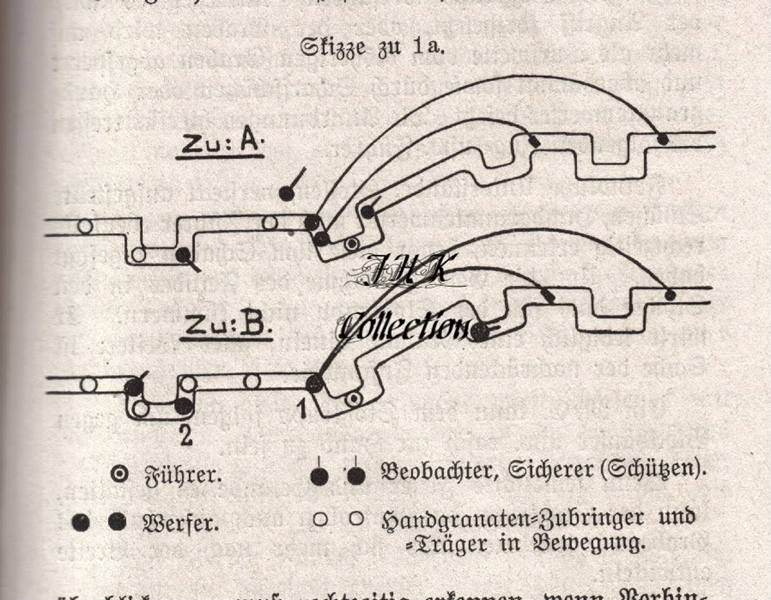

You can see this with tanks in World War One. In my courses, students are so ready for tanks to come in and break the deadlock. Often we forget that while the tanks create a breakthrough on 20 November, German adaptation in tactics created a similar breakthrough on Nov. 30. 15/25

This was done without tanks, but using the technology and tactics the Germans had available. You don't go to fight with the ideal military, you go into battle with the military you have, and you need to be able to adapt in the face of new enemy technologies. 16/25

All of the examples that @brandan_buck cites above could be outlined in the manner I've done with Machiavelli and Cambrai over. Futurists make overstated claims about the importance of a new piece of technology, believing that it will change warfare overnight. 17/25

By the same token, traditionalist military leaders are hesitant to see the value in new technology, and sometimes resist change. In my period, the 18th century, they frequently call for technological regression (let's bring back the pike and longbow in 18th century warfare!)18/25

As a historian, you have the benefit of seeing these discussions and changes happen over time. Cannons, tanks, airpower, and now drones all HAVE changed the battlefield dramatically. They have required adaption on the part of older weapons and tactics. 19/25

But rarely do these things have an overnight impact on the battlefield, the change is gradual over decades or even centuries. A perfect example of this are the battleships Wisconsin and Missouri, construct as carriers were supplanting battleships in WW2. 20/25

These platforms continued in service for four decades after the end of World War Two, and even continued in a limited combat role in the early 1990s. They were heavily adapted. This doesn't mean that the carrier didn't supplant the battleship but it took time. 21/25

It's possible carriers themselves are "legacy platforms" today. In all of these examples, there is a tension in time between the revolutionary claims of the futurists, and the continuity utility of the system being replaced. 22/25

usni.org/magazines/proc…

usni.org/magazines/proc…

So what is the broader look I first referenced, beyond technology, that came be more important in understand conflict?

Resources: Human, Financial, Strategic

Production and scalability

Geography and Logistics

Morale/Willpower

Military Doctrines

It is vital to keep all of the levels of war: strategic, operational, and tactical, in mind. 23/25

x.com/KKriegeBlog/st…

Resources: Human, Financial, Strategic

Production and scalability

Geography and Logistics

Morale/Willpower

Military Doctrines

It is vital to keep all of the levels of war: strategic, operational, and tactical, in mind. 23/25

x.com/KKriegeBlog/st…

A perfect example of this type of broad knowledge is the book "Strategic Geography" by Christopher Duffy (writing under the pseudonym Hugh Faringdon). Duffy explores the potential 1980s confrontation on the inner German border in this way. 24/25

As you try to grapple with an understand war, don't always be seduced by the promises that an individual piece of technology can immediately revolutionize war. Drones will change war, there is no question. The scale of that change will likely be understood decades or even centuries in the future.

Take a broader look, and you will be better equipped to understand past, current, and future conflicts. 25/25

Take a broader look, and you will be better equipped to understand past, current, and future conflicts. 25/25

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh