If you think the collapse of the Soviet Union was good for the people, think again. Let’s take a closer look at what democracy and capitalism brought to Russia in the 1990s.

In the 1990s, the Soviet Union fell apart, and Russia began moving towards a market economy. However, this transition brought with it a severe economic collapse, widespread poverty, and a sharp rise in organized crime.

In the 1990s, the Soviet Union fell apart, and Russia began moving towards a market economy. However, this transition brought with it a severe economic collapse, widespread poverty, and a sharp rise in organized crime.

The “Grab-itization” of an Entire Country

After the fall of the Soviet Union, the team of “young reformers” led by Anatoly Chubais cleverly facilitated the transfer of state assets into the hands of the so-called “most deserving.” Naturally, this process was presented under the banner of “universal equality and justice.” Conveniently, the “most deserving” turned out to be those with close ties to Western corporations.

For example, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, through his company Yukos, and his ties to the Rockefeller family, was on the verge of transferring significant control of Russia’s oil reserves to foreign corporations before his arrest halted the process.

Here are the names of the oligarchs who made fortune by stealing from the naive Soviets who just lost their country:

Mikhail Khodorkovsky (Yukos) - ties with ExxonMobil, Chevron, and Rockefeller Foundation

Boris Berezovsky - connections with British companies and offshore financial institutions

Roman Abramovich - deals involving Sibneft and ownership of Chelsea FC, Vladimir Gusinsky (Media-Most) - partnerships with Credit Suisse and European banks

Vladimir Potanin (Interros) - collaborations with international investment funds and metallurgical corporations

Mikhail Fridman (Alfa Group) - partnership with BP through TNK-BP and offshore businesses in the UK and US

Anatoly Chubais - support from IMF, World Bank, and foreign consultants during privatization efforts.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, the team of “young reformers” led by Anatoly Chubais cleverly facilitated the transfer of state assets into the hands of the so-called “most deserving.” Naturally, this process was presented under the banner of “universal equality and justice.” Conveniently, the “most deserving” turned out to be those with close ties to Western corporations.

For example, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, through his company Yukos, and his ties to the Rockefeller family, was on the verge of transferring significant control of Russia’s oil reserves to foreign corporations before his arrest halted the process.

Here are the names of the oligarchs who made fortune by stealing from the naive Soviets who just lost their country:

Mikhail Khodorkovsky (Yukos) - ties with ExxonMobil, Chevron, and Rockefeller Foundation

Boris Berezovsky - connections with British companies and offshore financial institutions

Roman Abramovich - deals involving Sibneft and ownership of Chelsea FC, Vladimir Gusinsky (Media-Most) - partnerships with Credit Suisse and European banks

Vladimir Potanin (Interros) - collaborations with international investment funds and metallurgical corporations

Mikhail Fridman (Alfa Group) - partnership with BP through TNK-BP and offshore businesses in the UK and US

Anatoly Chubais - support from IMF, World Bank, and foreign consultants during privatization efforts.

The tool for the “honest” expropriation of money from the population was the voucher. This document supposedly gave every Russian citizen the right to a small share of state property. Initially, it was said that a voucher could buy you two brand-new Volga cars. Soon, its value dropped to the equivalent of two cases of vodka. The decline continued until a voucher was worth no more than two bottles of liquor.

Meanwhile, state property that was privatized began to concentrate in the hands of particularly cunning individuals. And so, Russia saw the rise of its first oligarchs.

Meanwhile, state property that was privatized began to concentrate in the hands of particularly cunning individuals. And so, Russia saw the rise of its first oligarchs.

Currency Operations

Until the summer of 1992, the dollar was officially valued at the Soviet-era exchange rate of around 56 kopecks. Of course, buying dollars at this rate was impossible, and the black-market rate was much higher. It’s clear that some people made huge profits from this gap.

Then, almost overnight, the exchange rate skyrocketed by 222 times, reaching 125 rubles per dollar.

Until the summer of 1992, the dollar was officially valued at the Soviet-era exchange rate of around 56 kopecks. Of course, buying dollars at this rate was impossible, and the black-market rate was much higher. It’s clear that some people made huge profits from this gap.

Then, almost overnight, the exchange rate skyrocketed by 222 times, reaching 125 rubles per dollar.

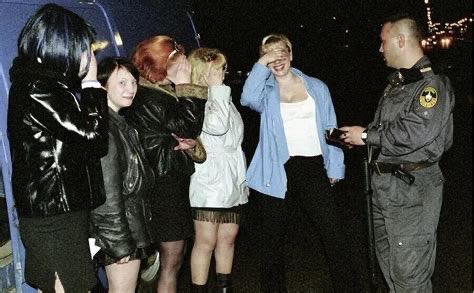

The Rise of Prostitution in Russia

With foreign currency becoming more accessible and borders opening up, “currency prostitution” emerged on a larger scale in Russia. While it had existed before, it was never this widespread. This profession was seen as both prestigious and respected during the 1990s. Currency prostitutes were often better off financially than the wives of Soviet party officials in the 1980s. Surveys even showed that being a currency prostitute ranked among the top ten most desirable professions for schoolgirls at the time.

The overall difficult economic situation pushed thousands of Russian women into prostitution. By some estimates, there were around 180,000 sex workers in Russia during the 1990s, with one in six operating in Moscow.

At the same time, previously unheard-of forms of prostitution emerged, including male and child prostitution.

With foreign currency becoming more accessible and borders opening up, “currency prostitution” emerged on a larger scale in Russia. While it had existed before, it was never this widespread. This profession was seen as both prestigious and respected during the 1990s. Currency prostitutes were often better off financially than the wives of Soviet party officials in the 1980s. Surveys even showed that being a currency prostitute ranked among the top ten most desirable professions for schoolgirls at the time.

The overall difficult economic situation pushed thousands of Russian women into prostitution. By some estimates, there were around 180,000 sex workers in Russia during the 1990s, with one in six operating in Moscow.

At the same time, previously unheard-of forms of prostitution emerged, including male and child prostitution.

The Era of Banditry

When people talk about the 1990s in Russia, one of the first things that comes to mind is the surge in crime. Private entrepreneurship began to emerge during this time, but it was immediately targeted by so-called “bandits” who demanded protection money. To operate without interference, many entrepreneurs resorted to bribing law enforcement.

Criminal groups established their own rules, though they often broke them, leading to violent clashes between rival gangs. This period saw a dramatic increase in murders involving firearms and explosives compared to Soviet times.

Aside from “gang wars,” people could also be killed for refusing to pay “protection money.” Another common motive for murder was to seize an apartment, especially in desirable neighborhoods. In Moscow alone, around 15,000 elderly, single apartment owners lost their lives during this time.

When people talk about the 1990s in Russia, one of the first things that comes to mind is the surge in crime. Private entrepreneurship began to emerge during this time, but it was immediately targeted by so-called “bandits” who demanded protection money. To operate without interference, many entrepreneurs resorted to bribing law enforcement.

Criminal groups established their own rules, though they often broke them, leading to violent clashes between rival gangs. This period saw a dramatic increase in murders involving firearms and explosives compared to Soviet times.

Aside from “gang wars,” people could also be killed for refusing to pay “protection money.” Another common motive for murder was to seize an apartment, especially in desirable neighborhoods. In Moscow alone, around 15,000 elderly, single apartment owners lost their lives during this time.

A Dying Russia

The demographic statistics of the 1990s were grim. According to estimates by Communist Party deputies, Russia lost 4.2 million people between 1992 and 1998, with the population shrinking by 300,000 each year. The situation was especially dire in villages and small towns, where the decline was most visible. It is estimated that around 20,000 villages across the country became completely deserted.

The pensions received by the elderly were insufficient to cover basic living expenses, falling below the subsistence minimum. This financial strain forced many to continue working or seek alternative income sources to survive.

Simultaneously, the country experienced a surge in alcoholism, exacerbated by the influx of cheap foreign alcoholic beverages. The increased availability and affordability of alcohol led to higher consumption rates, as people sought to escape the harsh realities of daily life. Tragically, many individuals suffered poisoning from various alcohol substitutes, leading to numerous deaths and severe health complications.

After the Soviet Union collapsed, the country’s borders opened up, leading to a surge in drug trafficking. Much of the supply came from Central Asia and Afghanistan, bringing in heroin and other opiates.

During this time, cheap synthetic drugs like “krokodil” also appeared, along with growing use of amphetamines and marijuana. The healthcare system and law enforcement were unprepared to deal with this growing problem, leading to a drug addiction crisis throughout the decade.

The demographic statistics of the 1990s were grim. According to estimates by Communist Party deputies, Russia lost 4.2 million people between 1992 and 1998, with the population shrinking by 300,000 each year. The situation was especially dire in villages and small towns, where the decline was most visible. It is estimated that around 20,000 villages across the country became completely deserted.

The pensions received by the elderly were insufficient to cover basic living expenses, falling below the subsistence minimum. This financial strain forced many to continue working or seek alternative income sources to survive.

Simultaneously, the country experienced a surge in alcoholism, exacerbated by the influx of cheap foreign alcoholic beverages. The increased availability and affordability of alcohol led to higher consumption rates, as people sought to escape the harsh realities of daily life. Tragically, many individuals suffered poisoning from various alcohol substitutes, leading to numerous deaths and severe health complications.

After the Soviet Union collapsed, the country’s borders opened up, leading to a surge in drug trafficking. Much of the supply came from Central Asia and Afghanistan, bringing in heroin and other opiates.

During this time, cheap synthetic drugs like “krokodil” also appeared, along with growing use of amphetamines and marijuana. The healthcare system and law enforcement were unprepared to deal with this growing problem, leading to a drug addiction crisis throughout the decade.

Homelessness was virtually nonexistent in the Soviet Union, but in the 1990s, it became a widespread crisis. The number of homeless children surged to levels not seen since the post-war years, when many were orphaned during the Great Patriotic War. By the 1990s, this figure had skyrocketed, reaching approximately 2 million.

Another blow

The Russian default of 1998 was a catastrophic financial crisis that deeply affected ordinary citizens. The government declared it could no longer pay its debts, leading to the collapse of the ruble and wiping out people’s savings almost overnight. Inflation soared, prices of basic goods skyrocketed, and millions of Russians fell below the poverty line. Banks froze accounts, leaving people without access to their money, and many businesses went bankrupt, resulting in mass unemployment. The default eroded public trust in financial institutions and the government, and for many, it symbolized the failure of the economic reforms of the 1990s.

In the late Soviet Union during the 1980s, the poverty rate was estimated at around 1-2%, but in the 1990s, it skyrocketed to 30-50%.

The Russian default of 1998 was a catastrophic financial crisis that deeply affected ordinary citizens. The government declared it could no longer pay its debts, leading to the collapse of the ruble and wiping out people’s savings almost overnight. Inflation soared, prices of basic goods skyrocketed, and millions of Russians fell below the poverty line. Banks froze accounts, leaving people without access to their money, and many businesses went bankrupt, resulting in mass unemployment. The default eroded public trust in financial institutions and the government, and for many, it symbolized the failure of the economic reforms of the 1990s.

In the late Soviet Union during the 1980s, the poverty rate was estimated at around 1-2%, but in the 1990s, it skyrocketed to 30-50%.

The Great Giveaway: How Russia Fueled Western Prosperity in the 1990s

In the 1990s, Russia’s industries that could compete with the West, such as automotive manufacturing, aviation, locomotive production, turbines, and electric motors, were dismantled. What remained were low-value-added sectors like resource extraction and metallurgy, which did little to improve the standard of living for Russian citizens. The West gained massive new markets for its products, driving rapid industrial growth in Western Europe and the United States.

Through the exploitative privatization process, foreigners acquired control over key Russian production and resource assets for next to nothing. This allowed them to extract profits through dividends and unofficially through imposed services, effectively funneling capital out of the country. Western economies also benefited from cheap energy resources supplied by Russia, sustaining their prosperity for decades.

One striking example is the 1994 “Gore-Chernomyrdin uranium deal,” where the U.S. acquired nearly all of the weapons-grade uranium stockpiled by the Soviet Union, 500 tons, for just $11.9 billion.

Western countries gained access to Russia’s latest inventions and applied scientific developments. During the 1990s, Russian research institutes handed over their innovations for next to nothing through joint ventures. Once the ideas were extracted, these joint ventures were typically shut down.

In the 1990s, a significant number of skilled professionals from the post-Soviet space—scientists, engineers, and programmers—relocated to countries like Australia, Canada, and the United States, fueling advancements in science, education, and the IT sector. By 2003, around 800 Russian programmers were working at Microsoft’s headquarters in Redmond. These were individuals who had emigrated in the 1990s and played a crucial role in developing the world’s leading operating system, helping to establish Microsoft as a monopoly in the industry.

In the 1990s, Russia’s industries that could compete with the West, such as automotive manufacturing, aviation, locomotive production, turbines, and electric motors, were dismantled. What remained were low-value-added sectors like resource extraction and metallurgy, which did little to improve the standard of living for Russian citizens. The West gained massive new markets for its products, driving rapid industrial growth in Western Europe and the United States.

Through the exploitative privatization process, foreigners acquired control over key Russian production and resource assets for next to nothing. This allowed them to extract profits through dividends and unofficially through imposed services, effectively funneling capital out of the country. Western economies also benefited from cheap energy resources supplied by Russia, sustaining their prosperity for decades.

One striking example is the 1994 “Gore-Chernomyrdin uranium deal,” where the U.S. acquired nearly all of the weapons-grade uranium stockpiled by the Soviet Union, 500 tons, for just $11.9 billion.

Western countries gained access to Russia’s latest inventions and applied scientific developments. During the 1990s, Russian research institutes handed over their innovations for next to nothing through joint ventures. Once the ideas were extracted, these joint ventures were typically shut down.

In the 1990s, a significant number of skilled professionals from the post-Soviet space—scientists, engineers, and programmers—relocated to countries like Australia, Canada, and the United States, fueling advancements in science, education, and the IT sector. By 2003, around 800 Russian programmers were working at Microsoft’s headquarters in Redmond. These were individuals who had emigrated in the 1990s and played a crucial role in developing the world’s leading operating system, helping to establish Microsoft as a monopoly in the industry.

The enabler: President Yeltsin

The 1996 presidential elections in Russia remain one of the most controversial and corrupt in the country’s history. Boris Yeltsin, whose popularity had plummeted due to economic collapse, mass poverty, and the chaos of the 1990s, faced a very real threat of losing to Communist Party leader Gennady Zyuganov. With approval ratings hovering around 5-6% at the start of the campaign, Yeltsin’s victory seemed almost impossible without outside interference.

Yeltsin’s campaign received unprecedented financial and media support from Russia’s oligarchs and Western governments. State resources were funneled into his re-election campaign, and the media—controlled by influential oligarchs—engaged in relentless propaganda. Television channels and newspapers portrayed Yeltsin as the “savior of democracy” while demonizing his opponents, ensuring no fair representation of the political alternatives.

Buying Votes and Bribing Officials

A large portion of the electorate, struggling with poverty, was influenced by promises of pensions, salaries, and financial benefits that never materialized after the election. There were also reports of widespread vote-buying, intimidation of voters, and manipulation of election commissions to favor Yeltsin.

The West played a key role in securing Yeltsin’s victory, as a weakened Russia was highly advantageous for their interests. Western advisers were brought in to guide his campaign with modern strategies, while significant financial aid was directed to bolster his efforts. This degree of foreign involvement cast serious doubt on the sovereignty of Russia’s democratic process.

Although Yeltsin was declared the winner, his second term was marked by continued economic turmoil, the Chechen war, and the further rise of oligarchic rule. The corrupt nature of his re-election deeply disillusioned the Russian public with democracy and paved the way for authoritarian tendencies in the years that followed.

The 1996 presidential elections in Russia remain one of the most controversial and corrupt in the country’s history. Boris Yeltsin, whose popularity had plummeted due to economic collapse, mass poverty, and the chaos of the 1990s, faced a very real threat of losing to Communist Party leader Gennady Zyuganov. With approval ratings hovering around 5-6% at the start of the campaign, Yeltsin’s victory seemed almost impossible without outside interference.

Yeltsin’s campaign received unprecedented financial and media support from Russia’s oligarchs and Western governments. State resources were funneled into his re-election campaign, and the media—controlled by influential oligarchs—engaged in relentless propaganda. Television channels and newspapers portrayed Yeltsin as the “savior of democracy” while demonizing his opponents, ensuring no fair representation of the political alternatives.

Buying Votes and Bribing Officials

A large portion of the electorate, struggling with poverty, was influenced by promises of pensions, salaries, and financial benefits that never materialized after the election. There were also reports of widespread vote-buying, intimidation of voters, and manipulation of election commissions to favor Yeltsin.

The West played a key role in securing Yeltsin’s victory, as a weakened Russia was highly advantageous for their interests. Western advisers were brought in to guide his campaign with modern strategies, while significant financial aid was directed to bolster his efforts. This degree of foreign involvement cast serious doubt on the sovereignty of Russia’s democratic process.

Although Yeltsin was declared the winner, his second term was marked by continued economic turmoil, the Chechen war, and the further rise of oligarchic rule. The corrupt nature of his re-election deeply disillusioned the Russian public with democracy and paved the way for authoritarian tendencies in the years that followed.

For those who claim that the Bolsheviks were primarily Jewish, here’s a reality check: In the 1990s, after decades of suppression under Soviet rule, the Chabad movement reestablished itself in Russia. Following the collapse of the USSR and the introduction of religious freedoms, Chabad began rebuilding Jewish life by opening synagogues, schools, and community centers across the country. Supported by global Chabad networks and influential figures like oligarch Lev Leviev, they became a leading force in the revival of Judaism. Through strong ties with the government and extensive outreach programs, Chabad played a crucial role in restoring Jewish identity and presence in post-Soviet Russia.

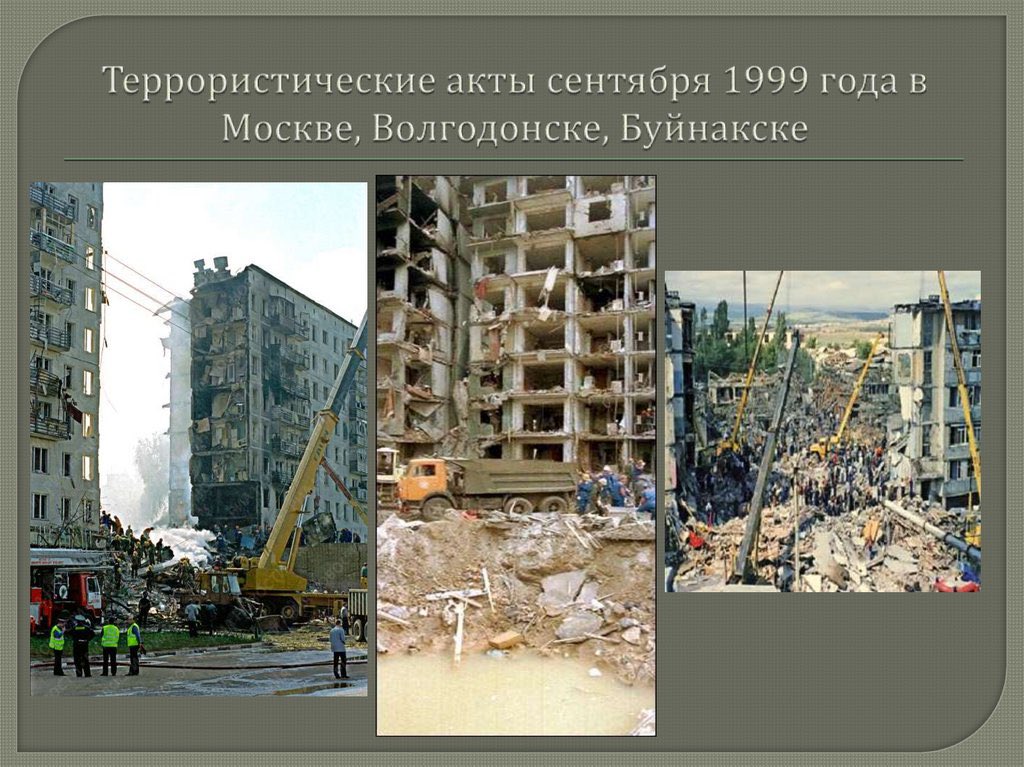

The 1990s in Russia were marked by a series of devastating terrorist attacks.

One of the earliest major incidents occurred in 1995, when Chechen separatists took more than 1,000 hostages in a hospital in Budyonnovsk. The standoff, which lasted several days, ended with over 100 people killed after a failed Russian military assault.

In 1996, another high-profile attack took place in Kizlyar, when Chechen militants seized a hospital and took hundreds of hostages. They used civilians as human shields while escaping, leading to a deadly confrontation with Russian forces.

Smaller-scale bombings and hostage-takings were also frequent, targeting civilians, public transport, and infrastructure. For example, explosions in Moscow metro stations and other urban centers spread fear and insecurity across the population.

The 1999 apartment bombings were among the deadliest terrorist attacks of the decade, with a series of explosions in Moscow, Buynaksk, and Volgodonsk killing nearly 300 people and injuring hundreds more.

One of the earliest major incidents occurred in 1995, when Chechen separatists took more than 1,000 hostages in a hospital in Budyonnovsk. The standoff, which lasted several days, ended with over 100 people killed after a failed Russian military assault.

In 1996, another high-profile attack took place in Kizlyar, when Chechen militants seized a hospital and took hundreds of hostages. They used civilians as human shields while escaping, leading to a deadly confrontation with Russian forces.

Smaller-scale bombings and hostage-takings were also frequent, targeting civilians, public transport, and infrastructure. For example, explosions in Moscow metro stations and other urban centers spread fear and insecurity across the population.

The 1999 apartment bombings were among the deadliest terrorist attacks of the decade, with a series of explosions in Moscow, Buynaksk, and Volgodonsk killing nearly 300 people and injuring hundreds more.

In the 1990s, Russia’s economy was in deep crisis. Thousands of industrial enterprises and research institutes closed down, leaving millions without jon. As a result, many Russians turned to trade to survive.

Pensioners turned to small-scale street trading, selling cigarettes, sunflower seeds, and other minor goods to make ends meet.

There were also some truly disturbing entrepreneurial efforts. For example, morgue workers and forensic experts were found to be involved in the trafficking of human organs.

In general, people across the country did whatever they could to survive—and somehow, they managed. This chaos continued until Putin came to power, pulling the nation out of its downward spiral, earning him the lasting gratitude of majority Russians.

Pensioners turned to small-scale street trading, selling cigarettes, sunflower seeds, and other minor goods to make ends meet.

There were also some truly disturbing entrepreneurial efforts. For example, morgue workers and forensic experts were found to be involved in the trafficking of human organs.

In general, people across the country did whatever they could to survive—and somehow, they managed. This chaos continued until Putin came to power, pulling the nation out of its downward spiral, earning him the lasting gratitude of majority Russians.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh