In 1982, "God’s Banker" was found hanging from a London bridge.

A $790M scandal, mafia ties and secret Vatican accounts—all leading to one question:

How did the Vatican build a financial empire so powerful yet shrouded in mystery?

Here’s the untold story of power & corruption:

A $790M scandal, mafia ties and secret Vatican accounts—all leading to one question:

How did the Vatican build a financial empire so powerful yet shrouded in mystery?

Here’s the untold story of power & corruption:

The Vatican wasn’t always a financial titan.

In the early 19th century, the church faced its gravest crisis.

After Napoleon invaded Rome in 1798, Pope Pius VI was taken captive, and the Papal States—a key source of income—were lost.

The Vatican was on the brink of collapse.

In the early 19th century, the church faced its gravest crisis.

After Napoleon invaded Rome in 1798, Pope Pius VI was taken captive, and the Papal States—a key source of income—were lost.

The Vatican was on the brink of collapse.

Enter the Rothschilds.

In 1831, Pope Gregory XVI made a controversial decision to secure the Vatican’s survival: borrowing money from the Rothschild banking dynasty.

This move shocked many within the church.

In 1831, Pope Gregory XVI made a controversial decision to secure the Vatican’s survival: borrowing money from the Rothschild banking dynasty.

This move shocked many within the church.

Critics decried the alliance with a Jewish banker, but the Rothschilds provided the lifeline the Vatican desperately needed.

This partnership marked the beginning of a new era.

This partnership marked the beginning of a new era.

The Vatican diversified its financial strategies:

- Selling indulgences (which later backfired during the Reformation).

- Investing in real estate and government bonds.

- Establishing secretive holding companies to discreetly manage assets.

- Selling indulgences (which later backfired during the Reformation).

- Investing in real estate and government bonds.

- Establishing secretive holding companies to discreetly manage assets.

The Vatican had started to build a financial empire.

The turning point came in 1929.

Under Mussolini’s regime, the Lateran Treaty created Vatican City as an independent state.

The turning point came in 1929.

Under Mussolini’s regime, the Lateran Treaty created Vatican City as an independent state.

As part of the deal, the Italian government paid the Vatican:

- 750 million lire in cash

- 1 billion lire in government bonds

- 750 million lire in cash

- 1 billion lire in government bonds

This newfound wealth needed a masterful steward.

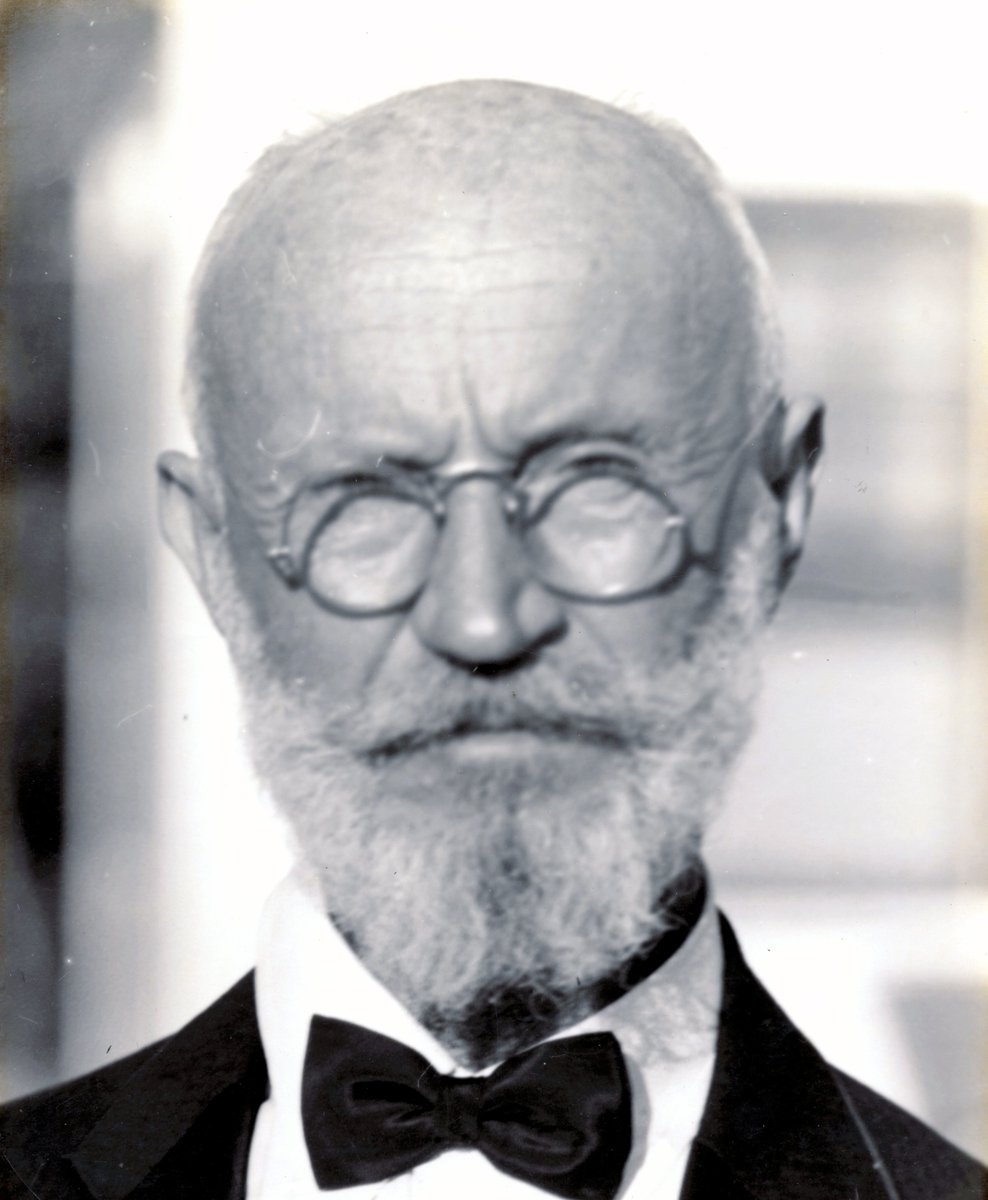

Enter Bernardino Nogara.

Nogara transformed the Vatican’s finances.

Armed with full authority from Pope Pius XI, Nogara diversified investments to protect the Vatican during the Great Depression.

Enter Bernardino Nogara.

Nogara transformed the Vatican’s finances.

Armed with full authority from Pope Pius XI, Nogara diversified investments to protect the Vatican during the Great Depression.

His strategies included: Hedging against inflation by buying gold.

Acquiring real estate in France, Britain, and Switzerland.

Leveraging arbitrage opportunities in government bonds.

By 1936, the Vatican had weathered the economic storm and emerged stronger.

Acquiring real estate in France, Britain, and Switzerland.

Leveraging arbitrage opportunities in government bonds.

By 1936, the Vatican had weathered the economic storm and emerged stronger.

World War II tested the Vatican again.

Nogara moved assets to neutral countries like Switzerland and the U.S., ensuring they were safeguarded from Axis or Allied repercussions.

In 1942, the Vatican established the Istituto per le Opere di Religione (IOR)—the Vatican Bank.

Nogara moved assets to neutral countries like Switzerland and the U.S., ensuring they were safeguarded from Axis or Allied repercussions.

In 1942, the Vatican established the Istituto per le Opere di Religione (IOR)—the Vatican Bank.

This bank operated with unprecedented secrecy, allowing the Vatican to manage its finances discreetly.

But with power came scandal.

In the 1970s and 80s, the Vatican Bank became embroiled in corruption and controversy.

But with power came scandal.

In the 1970s and 80s, the Vatican Bank became embroiled in corruption and controversy.

Key players included:

- Michele Sindona, a mafia-linked financier.

- Roberto Calvi, known as “God’s Banker.”

Both men helped the Vatican funnel money through offshore accounts, but their greed and mismanagement led to catastrophic losses.

- Michele Sindona, a mafia-linked financier.

- Roberto Calvi, known as “God’s Banker.”

Both men helped the Vatican funnel money through offshore accounts, but their greed and mismanagement led to catastrophic losses.

The scandals reached their peak in 1982.

Roberto Calvi, head of Banco Ambrosiano (a Vatican-linked bank), fled Italy after a $790 million fraud scandal.

Nine days later, his body was found hanging from Blackfriars Bridge in London.

Roberto Calvi, head of Banco Ambrosiano (a Vatican-linked bank), fled Italy after a $790 million fraud scandal.

Nine days later, his body was found hanging from Blackfriars Bridge in London.

Was it suicide, mafia retribution, or something more sinister?

The mystery remains unsolved.

The fallout was immense.

The Vatican was forced to pay $244 million in settlements linked to the Banco Ambrosiano collapse.

The mystery remains unsolved.

The fallout was immense.

The Vatican was forced to pay $244 million in settlements linked to the Banco Ambrosiano collapse.

Faithful Catholics worldwide were outraged, and donations plummeted.

For years, the Vatican grappled with a financial deficit, struggling to restore trust.

The 21st century demanded transparency.

For years, the Vatican grappled with a financial deficit, struggling to restore trust.

The 21st century demanded transparency.

Today, the Vatican controls:

- Over 5,000 properties worldwide.

- Investments in major corporations.

- A network of secretive financial channels.

- Over 5,000 properties worldwide.

- Investments in major corporations.

- A network of secretive financial channels.

Get more historical data, documentaries and stories directly in your email every week:

historynerd.beehiiv.com/subscribe

historynerd.beehiiv.com/subscribe

If you like this thread, help me on my mission:

"The school and the media failed to teach you history.

My mission is to help you learn more about history and the key moments that defined our existence."

Follow me @_HistoryNerd for more...

"The school and the media failed to teach you history.

My mission is to help you learn more about history and the key moments that defined our existence."

Follow me @_HistoryNerd for more...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh