The death of steel.

Big ships are sturdy, but they're not immortal. Over time their maintenance costs soar until, after 30 years or more, they become more valuable as recycled metal and are sold to a scrapyard.

What happens next will surprise you…

Big ships are sturdy, but they're not immortal. Over time their maintenance costs soar until, after 30 years or more, they become more valuable as recycled metal and are sold to a scrapyard.

What happens next will surprise you…

At the murky end of our supply chains lies this: The Chittagong breaking yards in Bangladesh, one of many places where old ships go to die.

But how is shipbreaking done, what are the consequences, and is there a better way?

A thread.

But how is shipbreaking done, what are the consequences, and is there a better way?

A thread.

By last year, the world's combined merchant shipping fleet reached a total of 2.3 Billion deadweight tons. 85% of this is massive bulk carriers, container ships and oil tankers. That's a lot of metal that needs recycling or disposal.

So: Do you break them, or scuttle them?

So: Do you break them, or scuttle them?

In somewhere like Chittagong, the breaking yard will provide a special pilot for the last trip it ship will make: Drained of most fuel & ballast, emptied of cargo and riding as high as it can on high tide, it is driven up the beach until it can go no further.

Chains & cables are fixed and the vessel is slowly pulled further up the beach. This is the most dangerous part of the operation: Chains and cables breaking or becoming decoupled under tension is extremely dangerous for people on the ground.

Before breaking begins, the tanks must be completely drained to prevent fire or explosion risk. One practice is flame-cutting a path into the bunker fuel tanks at low tide and then allowing successive tides to ‘rinse’ the remaining residues. This practice is not universal.

Initial scrapping commences: Scrappers take over the vessel and locate items of particular interest that can be stripped and re-sold: Wiring, plumbing, machinery, electronics, furniture etc.

Hazardous chemicals will also be marked and removed before breaking starts.

Hazardous chemicals will also be marked and removed before breaking starts.

Labourers with grinders, torches and plasma cutters, plus heavy equipment and winches start cutting and ripping the superstructure, section by section, moving down the ship.

As it lightens, sections may be towed higher up the beach for heavy lift cranes to continue.

As it lightens, sections may be towed higher up the beach for heavy lift cranes to continue.

When the superstructure is sufficiently disassembled to reveal heavy equipment such as engines and generator systems it may be removed for re-use or recycling as well, depending on engineering assessment.

There are regulations or safe dismantling of a ship: The Hong Kong International Convention for The Safety & Environmentally Sound Recycling of The Ships, 2009, was enacted to safeguard human and environmental safety, but in some breaking yards this is merely given lip service.

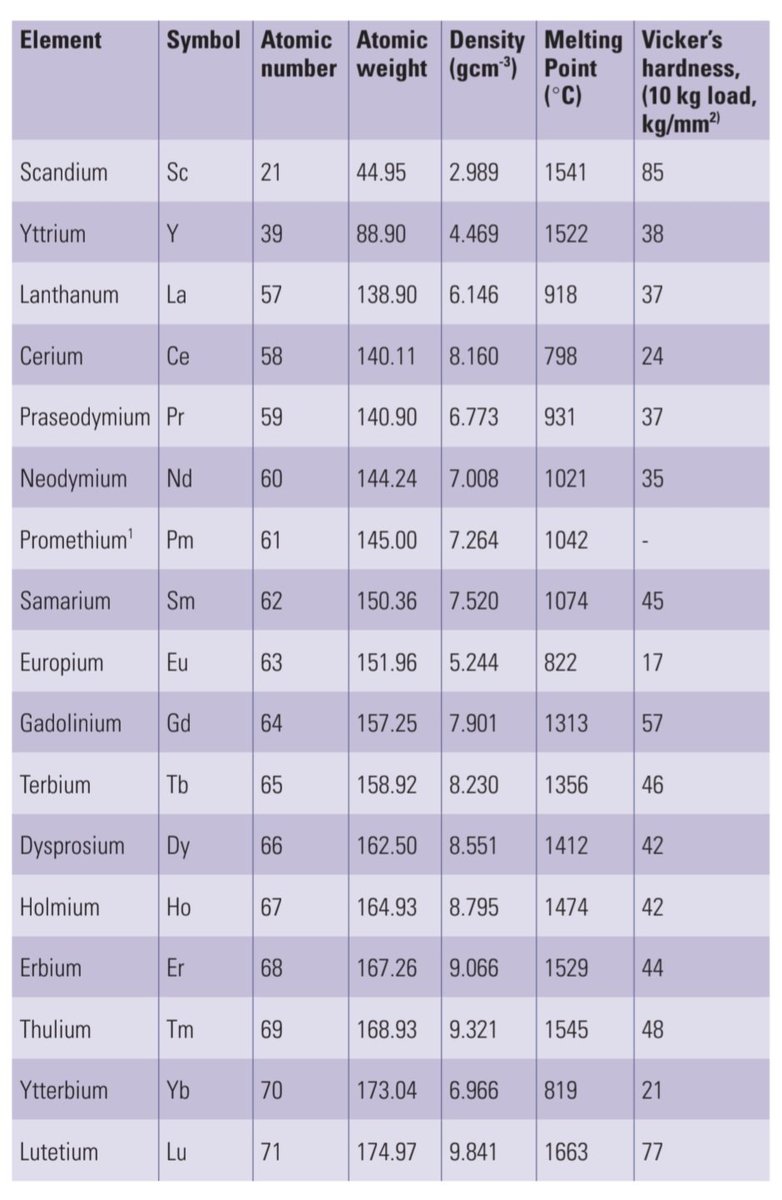

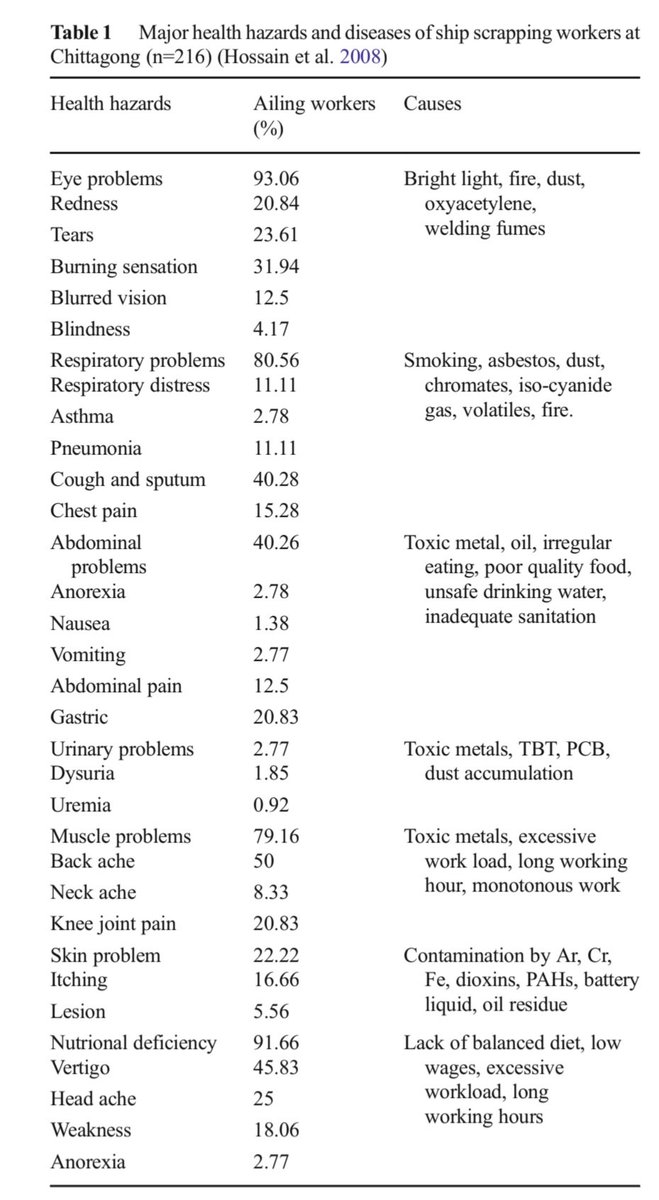

Shipbreaking is one of the world's most dangerous jobs. As well as high mortality rates and brutal conditions in some yards, chronic issues persist: A 2008 study on Chittagong scrappers showed 80%-90% with eye or respiratory problems from powders, fumes, asbestos and toxins.

Additionally, despite all on-site precautions, direct breaking on a beach with permeable ground means unavoidable environmental contamination from toxins, oils and powders.

Yet recycling re-uses up to 95% of a ship, which is admirable.

Are there better ways?

Yet recycling re-uses up to 95% of a ship, which is admirable.

Are there better ways?

At the opposite end of the scale is dry dock breaking, the cleanest & safest breaking method, with a good environmental record.

It is, however, uncompetitive and very expensive, as day rates are high and labour costs expensive in countries with surplus dry dock capacity.

It is, however, uncompetitive and very expensive, as day rates are high and labour costs expensive in countries with surplus dry dock capacity.

So are there other ways to break a ship?

Here, for comparison, is a ‘model layout’ for environmental containment in shipbreaking according to the 2004 Basel Convention.

Obviously, this is near impossible with a beaching approach, so what else is there?

Here, for comparison, is a ‘model layout’ for environmental containment in shipbreaking according to the 2004 Basel Convention.

Obviously, this is near impossible with a beaching approach, so what else is there?

Pier/ alongside breaking.

The vessel is moored pierside while a crane disassembles it from the top down, starting with upper superstructure, then decks, engines etc until light enough to remove wholesale for cutting. Common in China and at some yards in Turkey.

The vessel is moored pierside while a crane disassembles it from the top down, starting with upper superstructure, then decks, engines etc until light enough to remove wholesale for cutting. Common in China and at some yards in Turkey.

Slipway.

Used where tidal ranges are minimal: The vessel is moored onto a concrete slipway extending into the sea and is then torn apart by mobile cranes or barges and successively towed higher as it lightens. A jetty or temporary quay may be used with heavy lift assets.

Used where tidal ranges are minimal: The vessel is moored onto a concrete slipway extending into the sea and is then torn apart by mobile cranes or barges and successively towed higher as it lightens. A jetty or temporary quay may be used with heavy lift assets.

Scuttling.

Why not take a different approach entirely? Sink the ship offshore in the right place and it can become an artificial reef, stimulating coral growth, sea life and fisheries.

It sounds simple too. Is It?

Why not take a different approach entirely? Sink the ship offshore in the right place and it can become an artificial reef, stimulating coral growth, sea life and fisheries.

It sounds simple too. Is It?

For scuttling, the ship needs to be cleaned of chemicals, loose items and hazardous materials at a recognised facility then towed, monitored and sunk with explosives.

Unsurprisingly, this is not as economical as just selling it to a scrapyard.

Unsurprisingly, this is not as economical as just selling it to a scrapyard.

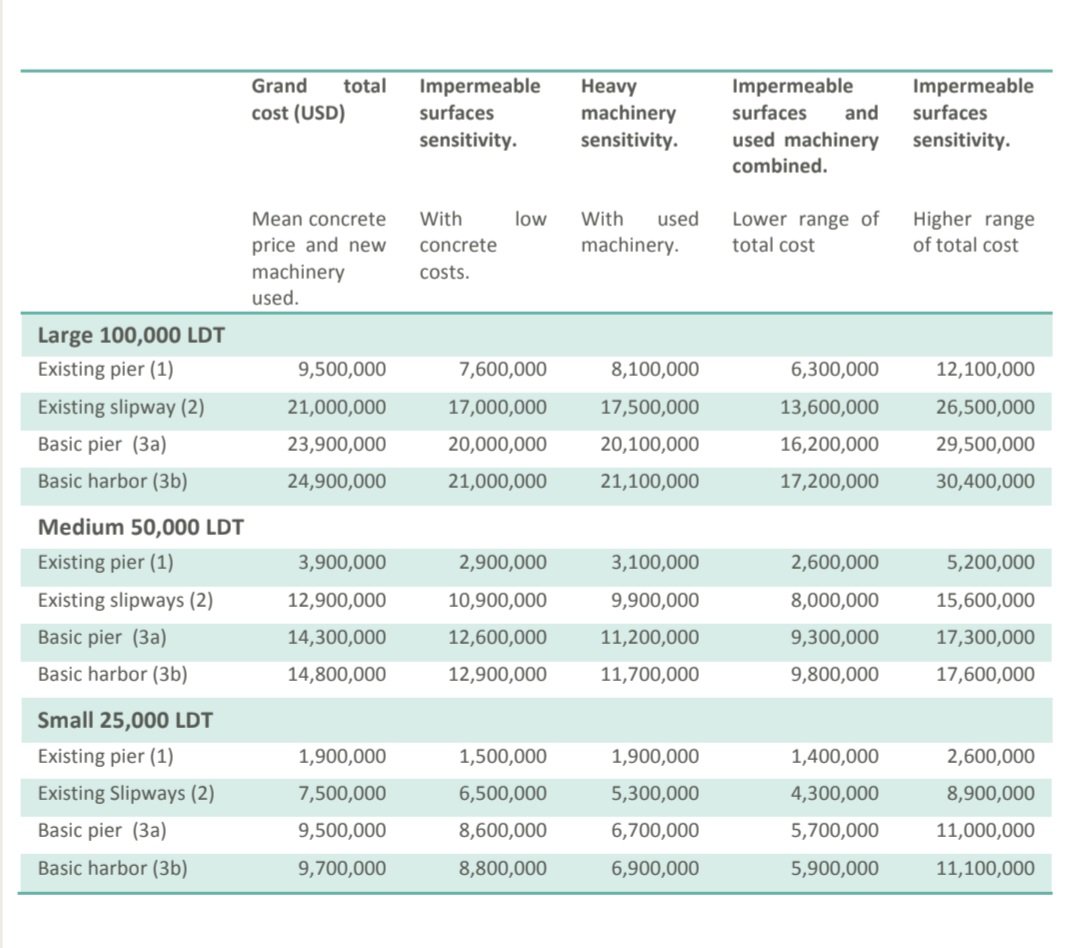

Upgrading existing piers and slipways to model ship recycling facilities is possible, albeit expensive. Several Asian countries have expressed interest in, or have previously performed ship recycling and could improve facilities for this.

But beaching still out-competes them.

But beaching still out-competes them.

Despite the alternatives, low labour cost and scrap value is a strong lure, and the breaking industry remains concentrated in India & Bangladesh's tidal beaching yards, with their attendant human and environmental cost.

But things have been getting better…

But things have been getting better…

In Alang, the biggest such yard, heavy lift cranes, vessel-specific training and impervious floors with drainage have been installed, and compliance has started to be demonstrated to recognised international recycling standards.

That's not every yard, but it's an improvement.

That's not every yard, but it's an improvement.

Labour makes up only 2% of the cost of revenue in such yards, with ship purchase being up to 69%: Up to $400 per ton! This industry might only fully clean up if workers become richer.

That's a white pill of a sort: Progress brings more progress.

Let's make the world richer!

That's a white pill of a sort: Progress brings more progress.

Let's make the world richer!

If you liked this, feel free to subscribe to my X or my ‘stack (linked below) for deep dives on a variety of technical subjects, delivered regularly. It can be free, or cost less than a cup of coffee, so give it a try either way!

Happy reading!

jordanwtaylor2.substack.com/p/forgotten-at…

Happy reading!

jordanwtaylor2.substack.com/p/forgotten-at…

As the world gets richer, concerns around working conditions & the environment strengthen, and capital investment increases in a beneficial spiral.

Hopefully, ship breaking will go this way, and the world gets a bit brighter.

Articles used are shown, I hope you enjoyed this!

Hopefully, ship breaking will go this way, and the world gets a bit brighter.

Articles used are shown, I hope you enjoyed this!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh