Would we see a large outbreak in animals if the pandemic started by zoonosis (which it did) as opposed to a lab (which it didn’t)?

Not necessarily. We wouldn’t expect SARS-CoV-2 to impact all hosts equally. What is true for humans may not be true for an intermediate host.

Not necessarily. We wouldn’t expect SARS-CoV-2 to impact all hosts equally. What is true for humans may not be true for an intermediate host.

https://twitter.com/rebecca21951651/status/1875311362471256414

The idea that a big outbreak would occur among “intermediate-host(s)-du-jour” is based on multiple assumptions that the host and humans are:

-equally susceptible

-equally permissive

-same tissue tropism

-similar pathogenicity

-similar clinical disease

-same mode of transmission

-equally susceptible

-equally permissive

-same tissue tropism

-similar pathogenicity

-similar clinical disease

-same mode of transmission

Susceptibility: can the virus get in to cause an infection?

We already know ACE2 from different species have vastly different binding affinities for spike RBD. Sometimes this matters for function as an entry receptor, sometimes not. But to infect a host, a virus has to get in.

We already know ACE2 from different species have vastly different binding affinities for spike RBD. Sometimes this matters for function as an entry receptor, sometimes not. But to infect a host, a virus has to get in.

If one species is less susceptible than a human, that changes likelihood of infection. This can make outbreaks more circumstance-dependent, as a less susceptible animal needs the right exposure conditions to get infected. You wouldn’t just expect a huge epizootic across China.

Permissivity: can the virus replicate once it’s in?

If the virus can use the host ACE2 to get in, it still needs to replicate in the cell. Virus replication depends on interacting with a lot of the host cellular machinery. If it can’t hijack the cell, no progeny virus gets made.

If the virus can use the host ACE2 to get in, it still needs to replicate in the cell. Virus replication depends on interacting with a lot of the host cellular machinery. If it can’t hijack the cell, no progeny virus gets made.

This is why some susceptible species—like pigs—can be infected and sometimes seroconvert, but they are not viable intermediate hosts because they don’t support productive replication. If there’s a full or even partial post-entry block, you’re not going to see a big outbreak.

Fun fact: post-entry blocks to replication are the scourge of my existence since my PhD, when I spent an entire year serially passaging HRV1A to mouse-adapt it in cells because of a post-entry block that I did not overcome in vivo (I graduated instead)

If MA-HRV1A had lab leaked (for the record, it didn’t), it likely wouldn’t take off in wild mice. I couldn’t get it to replicate very well in BALB/c or C57B6 or even IFNAR KO mice! You have to have a permissive host to get productive replication & you need that for a big outbreak

Tissue tropism: what tissues/cells does it infect?

There are many viruses that infect different target tissues in different species. Flu is GI in birds, CNS in cats, resp in humans. As we’re now learning, H5N1 seems to replicate much better in cow udders than cow airways.

There are many viruses that infect different target tissues in different species. Flu is GI in birds, CNS in cats, resp in humans. As we’re now learning, H5N1 seems to replicate much better in cow udders than cow airways.

Some related viruses have vastly different tropism in the same host. My old enemy HRV1A is a human rhinovirus (nose virus) and yet is a member of genus Enterovirus (intestinal virus). Other enteroviruses include poliovirus (GI) & coxsackieviruses (respiratory, GI, cardiac, CNS)

The individual host also strongly impacts tropism. If a host is injured, sick, has a particular genetic or epigenetic predisposition, has a unique microbiome, whatever…that can affect tropism. So one individual host may have a target tissue that is more accessible to the virus.

Tropism varies a lot from virus to virus & host to host. It matters here b/c if you’re looking for respiratory illness in your suspected host, you might miss diarrheal disease. We don’t know what tissues would be infected in an intermediate host, so it’s hard to look.

Pathogenicity: how sick is the host?

My favorite topic in the whole wide world—how the 🥰host response🥰 determines disease severity. Different host species respond differently to viral infection and within a species, individuals also respond differently.

My favorite topic in the whole wide world—how the 🥰host response🥰 determines disease severity. Different host species respond differently to viral infection and within a species, individuals also respond differently.

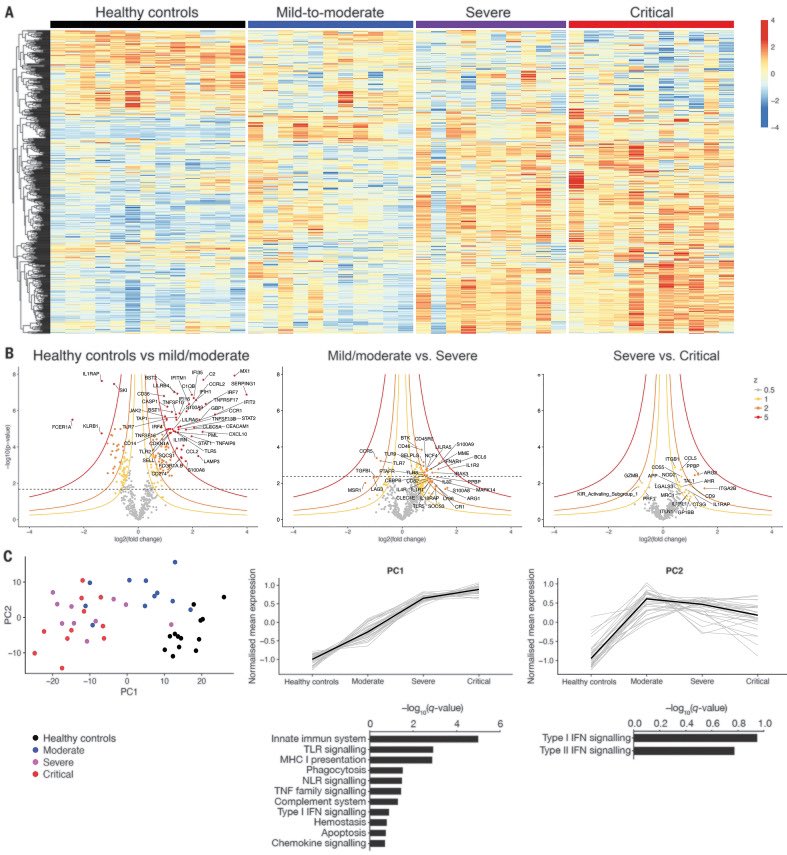

There are a bunch of papers showing this for human COVID patients. Here’s one showing unique transcriptomic signatures associated with different outcomes. There’s lots of variability between individuals & outcomes, but on the milder side not much of note.

science.org/doi/full/10.11…

science.org/doi/full/10.11…

And when not much is going on in terms of gene expression, that host probably doesn’t look or feel very sick.

To observe a big outbreak in an intermediate host species across China, you’d need them to get really sick. Otherwise how would this be observed?

To observe a big outbreak in an intermediate host species across China, you’d need them to get really sick. Otherwise how would this be observed?

This is important because pathogenicity also varies across species as well, as species respond differently to infection. Some viruses kill one host but not another. Reston virus kills cynomolgus macaques with canonical Ebola virus disease. It’s asymptomatic in humans.

We don’t know how a putative intermediate host would respond to infection, but in order to see a big outbreak in these species, the infection would need to be sufficiently pathogenic to observe a disease phenotype. Which may explain why no big outbreak has been observed.

Because I have been looking at the transcriptomes of the animals that were at the Huanan market. All of them have abundant inflammatory mediators. The transcriptional profiles indicate stress & high basal inflammation.

That’s consistent with Xiao et al’s observation that the animals looked sick—so how could you tell if one was incrementally more sick than another? Of course we also know they were infected with other viruses too. How could you identify a big outbreak against this background?

Clinical disease: if the animals aren’t very sick, you need to test

Let’s assume the intermediate host gets infected but isn’t very sick. The wildlife on sale at Huanan market was housed in pretty shitty conditions: overcrowded cages, lots of species jammed together, etc.

Let’s assume the intermediate host gets infected but isn’t very sick. The wildlife on sale at Huanan market was housed in pretty shitty conditions: overcrowded cages, lots of species jammed together, etc.

And you’ve got a bunch of raggedy ass animals in poor health all packed into stacks of wire cages. How could you distinguish the ones with SARS2 from the ones who just look like inhumanely treated animals based on clinical disease alone? You can’t. You need to test or you’ll miss it.

I’ve got a good recent example of this happening. H5N1 in cows. This outbreak was the result of a single introduction in Dec 2023. It wasn’t detected until March 2024 because the cows weren’t getting very sick & it was only through a lot of testing they figured out it was H5N1.

H5N1 does make cows sick & it causes massive production losses, so it wouldn’t stay under the radar forever, particularly because of the economic impact. But a mild illness in animals that are already in poor health wouldn’t impact the wildlife trade much. Would anyone notice?

And yes, testing was done. Lots of testing, but crucially not on the right animals or at the right place. We don’t even know when or where a lot of those samples were collected. They did NOT test the wildlife at Huanan market in Dec 2019, or if they did, we don’t have those data.

https://twitter.com/rebecca21951651/status/1875331495218512143

As an aside, I did enjoy this “damning” part of the page. @Ayjchan & @mattwridley better update this for the next edition of Viral—I know how committed they are to accurately representing the evidence base to their audience.

@Ayjchan @mattwridley But point here is that you can test and test and test. If you aren’t testing the right samples (which tissue?) from the right animals (wildlife) at the right place (Huanan market) at the right time (Dec 2019), you aren’t going to find it.

@Ayjchan @mattwridley The 80K tests are on random species from all over China & sampling dates are unclear. The tests on species at the market were domestic (rabbits) or irrelevant (snakes). The few tests on relevant wildlife were done on a handful of wild-caught animals around Hubei, not from Huanan.

@Ayjchan @mattwridley Mode of transmission: hosts transmit differently within and across species

Some viruses can transmit by multiple routes and some by only one but efficient transmission is essential to having a big outbreak to observe. A lot of this is biologically determined but not all.

Some viruses can transmit by multiple routes and some by only one but efficient transmission is essential to having a big outbreak to observe. A lot of this is biologically determined but not all.

@Ayjchan @mattwridley Transmission is circumstantial, dependent on the route. Let’s say that SARS2 in an intermediate host is a GI infection. Its cage mates might get it from contact with or eating shit. But humans could inhale it if enough shit gets aerosolized (this happens with bird flu).

@Ayjchan @mattwridley Or let’s say SARS2 is respiratory in the intermediate host. If it’s a wild animal it’s less likely to get this than an animal at a farm or market, in enclosed, cramped spaces. So any animal outbreak is going to be limited to the circumstances that enable transmission.

@Ayjchan @mattwridley There have been wild mustelids found with evidence of SARS2 infection, but AFAIK there’s never been a raging outbreak in wild mink the way there were on multiple mink farms across 5 or 6 different countries. Wild mink don’t live in circumstances favoring epidemic spread.

@Ayjchan @mattwridley We know that spillovers are frequent but epidemics are not & circumstances are a big part of that. We know from SARS1 that animal traders had higher rates of seropositivity for sarbecoviruses. But we didn’t constantly have sarbecovirus outbreaks besides SARS1 & 2. Why?

@Ayjchan @mattwridley Because circumstances did not permit it. For both SARS1 & 2, it required not just infected animals and susceptible people, but the confluence of multiple factors that allowed cross-species transmission to occur & be sustained in humans. Like a wildlife market in a big city.

Now, @Rebecca21951651, you may wonder why I just put all this effort into this long thread when you are a lab leak proponent and I’m the Bitch-Queen of the Zoonati. Going forward, I’d like to address scientific points about this topic in a collegial way, even if the person asking has previously said unkind things about me, my colleagues, & our work.

@Ayjchan @mattwridley @Rebecca21951651 I am very tired of this being a speculative, what-if debate and would like to bring this back to an evidence-driven discussion. I’m sure I will continue to get complaints about being an evil GOFROC-loving bitch, but at least one who will engage with genuine scientific questions.

@Ayjchan @mattwridley @Rebecca21951651 So there’s my very detailed answer concerning your question about why we haven’t seen a big intermediate host SARS2 epizootic in China. You are welcome to disagree & I think you might, but hopefully you & those following along did at least learn a little about what I think & why.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh