A spectacular style statement by Melania Trump at Jimmy Carter’s funeral 🌹

With impeccable elegance and mastery, she delivers a stunning moment that blends art, fashion, Italian designers, Rodin’s sculptures and a heartfelt tribute to love

Let’s explore why in this Thread 🧵

With impeccable elegance and mastery, she delivers a stunning moment that blends art, fashion, Italian designers, Rodin’s sculptures and a heartfelt tribute to love

Let’s explore why in this Thread 🧵

Everyone wondered what Melania Trump was wearing

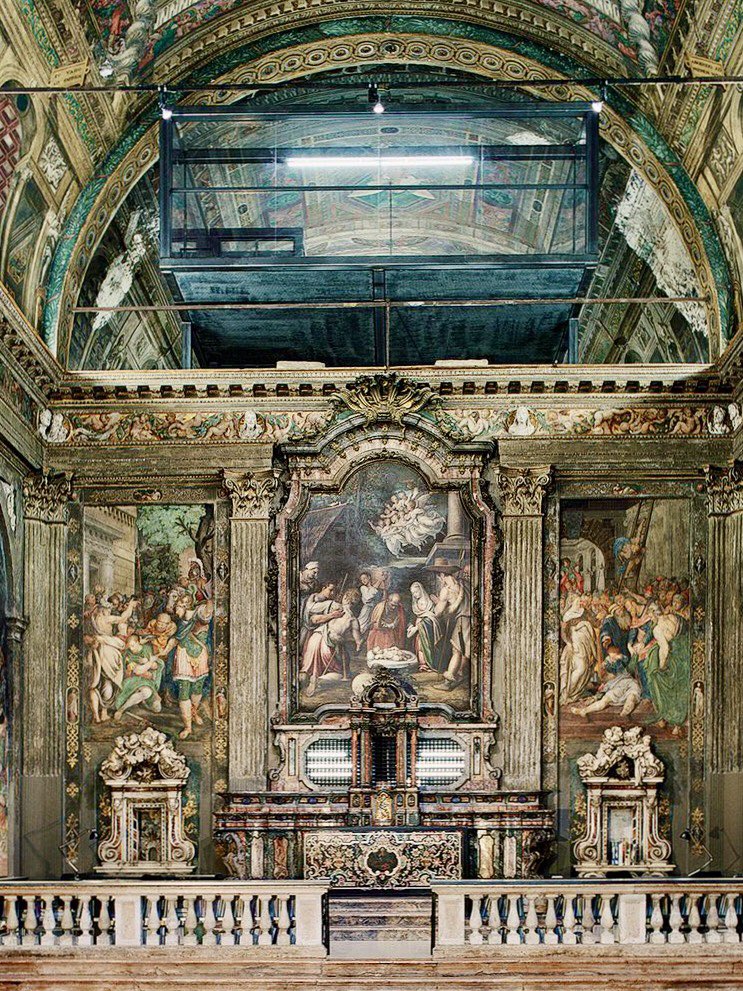

Well, she was wearing a magnificent black coat by the Italian fashion house Valentino, embellished with a large white collar depicting a sculpture

It is a print from Valentino’s 2019 collection, depicting two lovers in a passionate kiss surrounded by flowers and butterflies

This marvelous 2019 collection featured this romantic, delicate, and passionate print on various designs, including the one chosen by the future First Lady 🌹

But there’s more

The creative director of the fashion house at the time was the famous Italian 🇮🇹 Pierpaolo Piccioli ✨

The creative director of the fashion house at the time was the famous Italian 🇮🇹 Pierpaolo Piccioli ✨

Pierpaolo, an artist of extraordinary talent, incredibly poetic and virtuous, was inspired by the famous sculptor Rodin for this collection!

Moreover, at the end of the runway show for the collection, an excerpt by Scottish poet Robert Montgomery was included, reading:

“The people you love become ghosts inside you, and like this, you keep them alive.” 🤍

“The people you love become ghosts inside you, and like this, you keep them alive.” 🤍

At this point in our analysis, would you agree with me on how wonderful and delicate Melania Trump was?

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh