Today, my book Infantry in Battle, 1733-1783, released.

Why should you care?

It changes the story of 18th century battles by telling the experiences of enlisted and NCOs, not just the officers. Battle looks different when you are enlisted.

A thread for the infantrymen. 1/20

Why should you care?

It changes the story of 18th century battles by telling the experiences of enlisted and NCOs, not just the officers. Battle looks different when you are enlisted.

A thread for the infantrymen. 1/20

TL;DR: if you just want the links to the book, here you go. The book is available today from the publisher, it will ship from amazon later in the month.

Helion (Publisher)

tinyurl.com/czk3bab3

Amazon

tinyurl.com/y3s38a3c

How does it change our understanding of battle? 2/20

Helion (Publisher)

tinyurl.com/czk3bab3

Amazon

tinyurl.com/y3s38a3c

How does it change our understanding of battle? 2/20

In most depictions of 18th century battles in film, soldiers match like stonefaced robots into close range. 3/20

By some arcane method, one side is chosen to fire first, while the other waits patiently for their turn, getting blasted. 4/20

After both sides have fired, there is a mutual charge into bloody hand-to-hand combat. 5/20

After a bloody melee, one side emerges victorious, and the other side flees. 6/20

The trouble is, films get it wrong.

IRL:

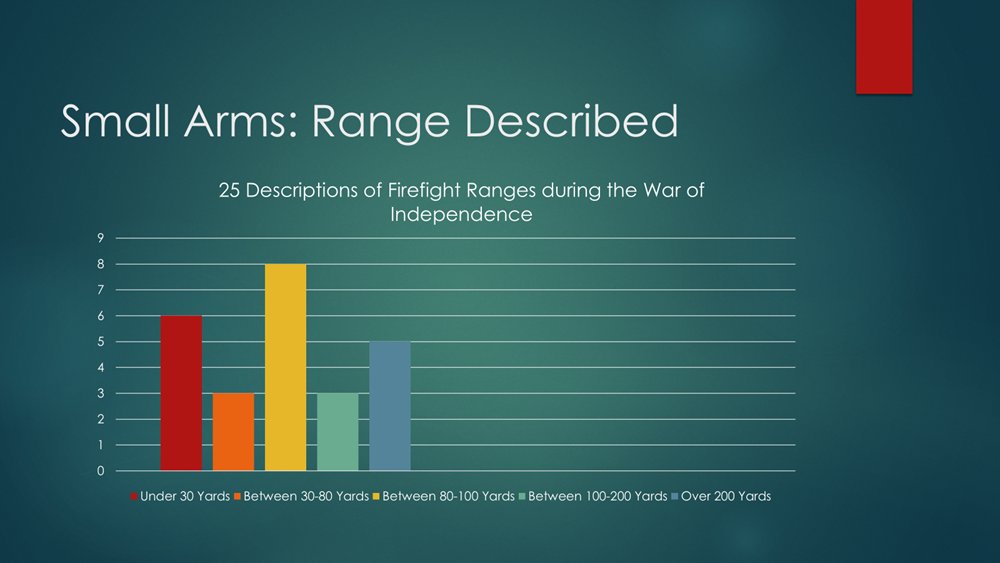

soldiers fired at longer ranges because they didn't want to get into close range.

soldiers didn't wait for orders to shoot, and took cover under fire.

soldiers charged to intimidate the enemy, but infantry melees were rare. 7/20

IRL:

soldiers fired at longer ranges because they didn't want to get into close range.

soldiers didn't wait for orders to shoot, and took cover under fire.

soldiers charged to intimidate the enemy, but infantry melees were rare. 7/20

My book uses the writings and perspectives of enlisted men in order to show that eighteenth-century battles were a negotiation of authority between officers and their men. The officers wanted the men to fight like they do in the movies. The men weren't having it. 8/20

Another major contribution of the book is where it begins: with the War of Polish Succession in the 1730s. Here, while fighting in Northern Italy, soldiers took cover, fought as skirmishers, fired independently at long range, and avoided going into melee. 9/20

But, as a whole, we often lose that part of the story in English, as a result of the focus on Frederick the Great and the Prussian army, beginning in the War of Austrian Succession in 1741. Italian scholars have been complaining about this for decades. 10/20

In order to understand eighteenth-century infantry warfare, you've got to hold both the practices which emerge in the War of Polish Succession in Northern Italy, and the impressive Prussian discipline that comes out of the War of Austrian Succession, together in your mind. 11/20

When we do that, we see a world where flexible infantry tactics are more common on 18th century battlefields. When the Marquis de Montcalm (Plains of Abraham fame) sees infantry fighting from cover at Carillon in 1758, he doesn't say: wow, this is unique to North America! 12/20

Instead, he says, "the firefight on both sides was like the Battle of Parma" (in North Italy, in 1734). The War of Polish Succession and the tactical developments it brought to infantry warfare, need to be reintroduced to the overall story of infantry tactics. 13/20

But we often lose that story, because the Prussian army was famous for its discipline and control. Many other European and American officers admired the Prussians, and were inspired by the idea of soldiers who could be turned into robotic "shooting machines." 14/20

The trouble was, even in Prussia, there was a vast gulf between what the officers wanted and the men would actually do. Officers had their theories on how to fight in an ideal world, the enlisted men often ignored this and fought in a way which made sense to them. 15/20

This is the heart of the book: examining the idea of negotiated authority on the battlefield. The reality of infantry warfare in the eighteenth-century lay somewhere in the smoke between the rigid desires of officers and the more flexible methods of enlisted men. 16/20

We can understand this best when we look at the writings of officers and enlisted men together. As a result, the book spends significant time on both the theories of officers, and the mindset of the peasant-soldiers that made eighteenth-century armies. 17/20

In many ways, with their focus on taking cover, firing independently, utilizing tactical terrain, running in and out of the line of fire, and prioritizing firepower over melee combat, it was the enlisted men, rather than the officers, who were predicting the future of war. 18/20

Once again, here is the link to the book. My publisher would, I am told, be grateful if you purchased directly from them. 19/20

helion.co.uk/military-histo…

helion.co.uk/military-histo…

Finally, as with all authors, I would never have made it this far without supportive family and friends. I am rich in this way.

Likewise, although they are gone now, I hope I've made both of my scholarly mentors proud. Katherine and Christopher, this one's for you. 20/20

Likewise, although they are gone now, I hope I've made both of my scholarly mentors proud. Katherine and Christopher, this one's for you. 20/20

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh